Abstract

Active participation of youth and surrogate decision-makers in providing informed consent and assent for mental health treatment is critical. However, the procedural elements of an informed consent process, particularly for youth in child welfare custody, are not well defined. Given calls for psychotropic medication oversight for youth in child welfare custody, this study proposes a taxonomy for the procedural elements of informed consent policies based upon formal and informal child welfare policies and then examines whether enacted state formal policies across the United States endorsed these elements. A sequential multi-method study design included: (1) semi-structured interviews with key informants (n = 58) primarily from state child welfare agencies to identify a taxonomy of procedural elements for informed consent of psychotropic medications and then (2) a legislative review of the 50 states and D.C. to characterize whether formal policies endorsed each procedural element through February 2022. Key informants reported five procedural elements in policy, including how to: (1) gather social and medical history, (2) prescribe the medication, (3) authorize its use through consent and youth assent, (4) notify relevant stakeholders, and (5) routinely review the consenting decision. Twenty-three states endorsed relevant legislation; however, only two states specified all five procedural elements. Additionally, the content of a procedural element, when included, varied substantively across policies. Further research and expert consensus are needed to set best practices and guide policymakers in setting policies to advance transparency and accountability for informed consent of mental health treatment among youth in child welfare custody.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Medications to manage emotional and behavioral health problems (hereafter, “psychotropic medications”) are prescribed to increasing numbers of children in the United States (US), including more than one-quarter of the approximately 400,540 children removed from their caregiver of origin and placed into child welfare (hereafter, “youth in child welfare custody”; Crystal et al., 2009). Concerns around the safe and judicious use of psychotropic medication among youth in child welfare custody exist due to observed prescribing patterns. Studies find that the target symptoms for prescribing of specific classes of psychotropic medications (e.g., antipsychotic medications) do not align with FDA-approved indications or where the evidence base for their use is strongest (Chen et al., 2021; Christian et al., 2013; Mackie et al., 2020a, 2020b). Other concerns include youth in child welfare custody are not receiving psychosocial treatment as a first line of treatment, as well as lack of blood glucose and serum cholesterol monitoring for potential cardiometabolic side effects (Crystal et al., 2016).

In response, federal government and legislators made calls for the United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), state legislators, and public sector agencies to, promote psychotropic medication oversight among children in foster care (Barnett et al., 2016b). For example, the Government Accountability Office conducted multiple federal investigations, including a report entitled “Foster Children: HHS Has Taken Steps to Support States’ Oversight of Psychotropic Medication but Additional Assistance Could Further Collaboration” (Government Accountability Office, 2011; Government Accountability Office, 2017). Moreover, the enactment of two pieces of federal legislation, the Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act of 2008 (P.L. 110-351; 2008) and the Child and Family Services Improvement and Innovation Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-34 2011; 2011) required Title IV-B and Title IV-E funded child welfare agencies to develop protocols for oversight of health and mental health services and psychotropic medications specifically for youth in child welfare custody, respectively. Prior research suggests that child welfare policymakers mobilized multiple types of evidence, both “global” and “local” to their respective jurisdiction, to inform their respective responses to these federal calls to provide additional psychotropic medication oversight (Hyde et al., 2016).

In response to these federal calls for additional oversight, a rapid expansion of system-level psychotropic medication oversight policies for children in child welfare custody emerged and is well documented (Mackie et al., 2017). Prior studies suggest that 45 of the 50 states and D.C. implemented at least one system-level strategy to provide psychotropic medication oversight for youth in child welfare custody by 2013. The extensive set of state actions reflect, in part, that youth in child welfare custody present a unique set of legal and ethical responsibilities for the state and/or county child welfare agencies. These agencies serve in loco parentis or “in place of the parent” for such youth. As a result, the state assumes unique responsibilities in ensuring oversight and a meaningful informed consent process for youth in their care.

While studies have investigated how states mobilized in response to calls for greater oversight (Hyde et al., 2016) and whether policies exist regarding informed consent of psychotropic medications for youth in child welfare custody (Naylor et al., 2007; Noonan & Miller, 2013), limited attention has been given to the procedural elements of the informed consent processes endorsed by child welfare policies and the comprehensiveness of state policies in the United States. Accordingly, this paper proposes a taxonomy for the procedural elements of an informed consent process for psychotropic medication use among youth in child welfare custody and examines whether these procedural elements are endorsed in the formal policies enacted across the United States.

Defining Informed Consent and Assent

Informed consent is seen as a critical component of patient-centered mental health care (Braithwaite & Caplan, 2014). Informed consent is defined as a process of consent that is based on the provision of the information required for an individual to exercise fully their decision-making authority (Katz & Webb, 2016), consisting of ethical, legal, and administrative dimensions (Hall et al., 2012). Procedural elements viewed as important for informed consent vary depending on professional guidelines, but generally seek to ensure: (1) assurance of capacity for the decision-maker to provide consent, (2) provision of information in a language understandable to the decision-maker, (3) assessment of understanding of the information, including associated risks and benefits, provided to the decision-maker and (4) documentation of consent (Katz & Webb, 2016). These procedures are generally understood to provide legal protection (e.g., preventing assault and unwanted procedures), ethical assurances (e.g., protecting patient autonomy, preferences and decisions), and administrative documentation of patients’ involvement (Hall et al., 2012).

Assent aims to ensure meaningful input from the patient as an active participant in their care and that they ultimately agree to receive the treatment, even if not granted legal decision-making authority (Katz & Webb, 2016). In this process, a clinician will: (1) establish developmentally appropriate awareness of the condition with the patient, (2) create and communicate an individualized care plan relating to treatments/procedures, (3) assess the patient’s comprehension of the care plan, and (4) work with families and patients to resolve areas of conflict and determine patient’s assent to treatment (Katz & Webb, 2016; Mosca et al., 2005). At each step of the informed consent or assent process, clinicians are encouraged to present care options clearly and in a manner that is developmentally appropriate for the patient.

Informed Consent for Youth in Child Welfare Custody

Studies of youth, caregiver, and clinicians have highlighted the need for additional practices of patient-centered care in prescribing psychotropic medications, including the informed consent process, for youth in child welfare custody (Barnett et al., 2019). For example, a systematic review of studies investigating the patient-centeredness of psychiatric care found a pervasive lack of knowledge, limited decision-making agency, and imbalanced power between patients and providers (Barnett et al., 2019). In the informed consent process specifically, youth formerly in child welfare custody, their caregivers, and provider report the need for: (1) communication, (2) comprehension, (3) youth involvement and agency, (4) stakeholder accountability, (5) consideration of the trade-offs in having a mandated authority, (6) collaboration, and (7) attention to potential treatment delays due to informed consent processes (Simmel et al., 2021).

State Regulation of Informed Consent

In response to these concerns, formal policies have the potential to provide procedural assurance that consent is truly informed, including elements such as transparency, accountability, and the principles of shared decision-making in informed consent procedures for mental health treatment (Barnett et al., 2019; Noonan & Miller, 2013). Broadly speaking, informed consent often is supported through legal requirements that may be outlined to varying extent through statutes, regulation, and case law across the states (Ginsberg, 2010). Among these, formal policies refer to legislation and associated regulations, statutes, and administrative code that are enacted through a public process generating a legally binding statute or rule (Noonan & Miller, 2013). Formal policies may be endorsed either as laws enacted by the legislature (in the form of statutes) or rules endorsed by an administrative agency in the form of administrative code (Rinfret et al., 2018). In contrast, informal policies are typically established as “guidance documents,” consisting of non-legislative or interpretive rules and states generally do not require any notice or comment before guidance documents are issued (Noonan & Miller, 2013). Prior studies argue that formal informed consent policies-as opposed to informal ones-promote transparency, public discourse, and protection in cases of surrogate decision-making with vulnerable populations, including youth in child welfare custody (Noonan & Miller, 2013). Notably, class action litigation has generated considerable reform in mental healthcare service delivery for youth in child welfare custody, including influencing the development of formal policies to ensure accountability and transparency in mental health oversight (Oppenheim et al., 2012).

Study Objective

This article characterizes the procedural elements of child welfare policies that endorse an informed consent process for psychotropic medications among youth in child welfare custody. We then sought to examine whether and how these procedural elements are reflected in formal state policies across the United States.

Methods

Study Design

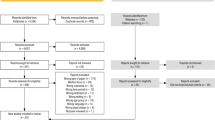

We employed a sequential multi-method design. First, we conducted semi-structured interviews in 2009 and 2010 to provide an in-depth study on states’ responses to PL 110-351 and to create a taxonomy of the procedural elements of informed consent policies articulated by mid-level administrators. Qualitative methods, like those used by our research, are appropriate and frequently engaged to develop taxonomies (Patton, 2002). In this article, we use the term “taxonomy” to refer to a formal system of classification, specifically classifying procedural elements of informed consent to identify a set of common conceptual domains. We subsequently conducted a legislative review to refine and improve this taxonomy as well as characterize existing informed consent policies nationally. Collectively, this multi-method approach permitted development of a taxonomy for understanding policy approaches to informed consent for youth in child welfare custody and characterization of existing state legislation using this taxonomy. The Institutional Review Board at [institution withheld to preserve anonymity] reviewed and approved the study protocol.

Taxonomy Development

Semi-structured interviews provided the source for taxonomy development that we then applied to the legislative analysis.

Sampling Framework

Our sampling framework prioritized key informants in child welfare agencies, given the responsibility of these agencies to serve in loco parentis. Interview data were collected from 48 states including the District of Columbia (D.C.; hereafter ‘states’) out of a possible 51 (response rate: 94.1%). While two of the 58 key informants arrived from the Governor’s Office and the State Department of Health, the remainder held a wide range of roles within child welfare, including Program Officers (n = 16), Medical or Mental Health Directors/Specialists (hereafter, “Medical Directors” or “Mental Health Directors,” respectively; n = 12), and Deputy or Associate Directors of Policy and/or Practice (n = 6), among others (n = 22).

A trained research assistant identified key informants through online searches of state websites, a search of the National Association of State Foster Care Managers website, and a search of the Child Welfare Information Gateway website. The research assistant then contacted the informant by telephone to confirm receipt of the informed consent and willingness to participate, to ensure the subject was the best available informant, and to schedule the interview. We engaged a purposive and referral sampling strategy to ensure adequate response to the questions in the interview guide. If the first contact had insufficient information to answer all the questions, we asked that person to refer us to the appropriate informant in their state. In one state, an informant responded to our interview, but did not name other informants. Partial data points are presented for that state. Our team recruited a key informant from another sector (e.g., Governor’s Office, State Department of Health) only when a policy/guideline was developed or managed by that agency.

Measures

The interview included 61 closed and open-ended questions with additional probes for use when necessary. The guide sought to: (1) identify the status of state policies and programs designed to provide evaluation and psychotropic medication oversight for youth in child welfare custody, (2) examine procedural elements of child welfare medication oversight initiatives, and (3) identify potential best practice models used by states to improve medication oversight for youth in foster care. The present article relies on data about the informed consent policies specifically, drawing on three questions in particular: (1) the procedural elements of formal and informal informed consent policies for psychotropic medications among youth in child welfare custody, (2) the individual(s) vested with authority to consent and/or whether youth assent for psychotropic medication use, and (3) the additional resources deployed to inform consenting and/or assenting decisions.

Study Procedures

The interview guide received review from an interdisciplinary research team and was subsequently pilot tested with three child welfare mid-level administrators who provided consultation on these processes. Following external expert review and pilot testing of the interview guide, the research team administered the interview by telephone between March 2009 and January 2010. An experienced and trained research assistant used the study guide and recorded data by hand-written notation. Our team used this notation process because the goal was to understand the status and conceptualization of policy, program, or procedures rather than more complex social phenomenon investigating the lived experience of study respondents (Bertrand et al., 1992). The average duration of the interview was approximately 60 min. No child or case-specific data was obtained during the interview.

Analysis

Employing the five steps of framework analyses (Srivastava & Thomson, 2009), three investigators initially identified a thematic framework for psychotropic medication oversight, including informed consent policies, among youth in child welfare custody. In this article, we summarize the findings that related specifically to informed consent policies. The research team indexed key aspects of informed consent policies, including: (1) the procedural elements described; (2) the individual with consenting authority; and (3) the resources available to support the consenting authority in decision-making. For each of the domains indexed, our team then conducted a priori and emergent codes to analyze the indexed data, using a process of thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). For example, the research team identified the procedural elements based upon both emergent and inductive findings as well as the extant literature, specifically drawing on guidelines published by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 2015) for psychotropic medication treatment. Accordingly, our team identified procedural elements for informed consent policies that included processes to gather, prescribe, authorize, notify, and then follow-up and review the prescribing decision. The resulting taxonomy, using data from 2009 to 2010, provided the framing for the legislative review.

Legislative Review of Formal State Policies for Informed Consent

Based on the taxonomy identified from the semi-structured interviews, we conducted a systematic legislative review to examine the extent to which the elements of the taxonomy were formalized in state laws and regulations. To identify the laws in place nationally, the systematic legislative review examined state-level statutes and regulations relating to informed consent and the administration of psychotropic medications for youth in child welfare custody across all 50 states and D.C. on or before February 1, 2022. Legislative review is an optimal approach to systematically identify and characterize the presence of a formal policy delineating informed consent procedures required of youth in child welfare custody (Noonan & Miller, 2013). We employed WestLaw (Thomson Reuters Corporation, New York, NY), a repository of state statute and regulations for the 50 states and D.C. to identify relevant legislation.

Development of Search Strategy for Legislative Extraction

We identified search terms through a preliminary literature review and included the following domains: (1) psychotropic medications, (2) informed consent and/or assent (Naylor et al., 2007), (3) children and/or youth, and (4) foster care and/or child welfare (see Appendix 1) (Noonan & Miller, 2013). Two researchers then reviewed a sample of initial results [six states] to determine appropriateness of search terms. Based on preliminary search, we added “permission” to the search terms used for the review. We then conducted full-text searches for all 50 states and D.C. using the search terms for each policy document.

Extraction of Legislation

Based on search terms, we initially identified 1140 regulations and statutes, including 385 statutes and 755 regulations. Two researchers reviewed all statutes and regulations to determine whether applicable to the informed consent process for psychotropic medications, and applicable to youth in child welfare custody. We considered laws to be outside the scope of our study if they did not explicitly reference youth in child welfare custody. For example, laws targeting youth in juvenile justice facilities, without any specifications for informed consent among youth in child welfare custody, were excluded. Laws were exported into an Excel spreadsheet for analysis. After applying exclusion criteria, 48 state laws remained, including 13 statutes and 35 regulations. See Appendix A for a final list of state laws in effect on or before February 2022 which were identified using Westlaw.

Data Analysis

Three researchers initially analyzed statutes and regulations that met criteria for inclusion from six states. Identifying a priori categories (based on the procedural elements of informed consent derived from semi-structured interviews) and emergent categories, an initial codebook was developed and received review from a developmental behavioral pediatrician, social work policy scholar, and health services researcher. Therefore, the research team triangulated the domains established from the semi-structured interviews with key elements of procedural elements identified in the legislative review; thematic areas corroborated across the respective data sources. Accordingly, a preliminary codebook was then established specifying the procedural elements and other policy characteristics of informed consent policies. After the codebook was established, two researchers systematically reviewed all extracted statutes/regulations and coded a priori (by relevant text by domain such as each of five procedural elements) and emergent (e.g., setting) domains. Although the need never arose, the protocol stated a third reviewer would be consulted in cases where the first two reviewers could not arrive at consensus.

After coding data by procedural element or policy characteristic (i.e., setting), three researchers subsequently conducted an additional emergent thematic analysis of the excerpted data for each element. Investigators read the textual data of all excerpts in an element and provided an open code to capture detailed information about each procedural element. Based on the open coded responses, we then expanded the initial codebook of procedural elements and settings to capture the “child codes,” denoting characteristics of the respective procedural element. To categorize setting, two investigators reviewed the language used to capture the setting in which a policy applied for youth in child welfare custody. The two investigators coded the setting for which a policy applied using the language of the legislation itself wherever possible, resulting in the list of settings identified in the results. At least two members of the research team reviewed all codes. We then assessed the relative frequency and variation of procedural elements in informed consent policies and the content of these policies to determine the frequency and heterogeneity in reporting of procedural elements for informed consent.

Results

A Taxonomy of Procedural Elements for Informed Consent among Youth in Child Welfare Custody

For youth in child welfare custody, respondents articulated the potential for five procedural elements of an informed consent policy. As defined in Table 1, the five procedural elements of an informed consent policy included specification of how to: (1) gather the social and medical history of the youth in child welfare custody, (2) specify the activities required to inform the decision to prescribe (or not to prescribe), (3) authorize (or not authorize) the psychotropic medication(s) prescribed through consent and/or youth assent, (4) notify relevant stakeholders, and (5) review the informed consent decision for psychotropic medication use for youth in child welfare custody. Table 1 provides the definition for each of these procedural elements and the operational definitions engaged in the legislative review conducted. Description of the extent to which these elements were applied in the reviewed legislation concludes the results.

Legislative Review

Once our taxonomy of procedural elements for an informed consent policy was identified, we used this taxonomy to classify the policies identified through a legislative review. Across the 50 states and D.C., 23 states (including D.C.) had at least one statute or regulation that specified a procedural element of informed consent. Figure 1 illustrates the location of states nationally having endorsed policies, specifically detailing the number of articles of legislation provided. Twenty-three states (including D.C.) had enacted 48 pieces of legislation, ranging from one to six articles per state. Enacted articles were endorsed between 1974 and 2022.

Of the 23 states that had enacted at least one legislative article, only two states (OR, CA) specified all five procedural elements of informed consent. All 23 states specified the process for authorizing the use of psychotropic medication, including designation of the individual with authority to consent for youth in child welfare custody. Specification of parameters for prescribing the psychotropic medication for youth in child welfare custody and gathering the medical and social history of the youth were the second and third most frequently specified elements, endorsed by policies in 18 and 13 of the states, respectively. Six states enacted policies that specified who would be notified of the consenting decisions. In six states, the policies specified a process for the authorizing individual to revisit the informed consent decision at a later time. Table 2 provides a summary of the procedural elements endorsed by informed consent policies across the 23 states.

Specification of a Subset of Youth in Child Welfare Custody

Youth in child welfare custody may be placed in a variety of different settings, such as foster care, group homes, and residential treatment settings. Of the 48 policies enacted for youth in child welfare custody, almost half of these policies (22, 46%) applied to all youth in child welfare custody while the remainder applied to a subset of youth in child welfare custody based upon the treatment setting or placement. As noted in Table 3, 14 of the 50 states and D.C. held policies that applied to all youth in child welfare custody, whether in a state- or county-administered system.

Gathering of Social and Medical History

A requirement for specific information to be gathered and consulted prior to the prescribing decision was specified in 19 policies across 13 states (including D.C.). Procedural elements of an informed consent process initially required information to be gathered on the medical and medication history of the child and to collect information from caregivers or other collaterals about the child’s social and/or medical history. As described in Table 4, informed consent policies in 11 states indicated the need to gather a medical history broadly defined, six states stated the need for a medication history specifically, and five states endorsed informed consent policies that emphasized the need to acquire relevant information from collaterals.

Specification of Activities Required During the Clinical Encounter

Policies for informed consent may require the prescribing clinician to conduct specific actions when deciding to prescribe the medication. Our analyses of the legislation identified multiple activities that were required during the process of prescribing the psychotropic medication, including: (1) specifying the protocol for how to conduct the mental health assessment, (2) sharing information on the prescription, (3) conducting relevant laboratory tests, and (4) specifying the need and process of monitoring for potential side effects. Requirements of the clinical encounter prior to prescribing psychotropic medications were stated in 26 policies across 17 states (including D.C.).

Of the 17 states with an informed consent policy specifying procedural elements at the clinical encounter, 15 states required that information be shared regarding the prescription medication, such as requirements for administration of the prescribed medication and side effect profile. In specifying the procedural elements of prescribing, states most commonly specified provisions for a mental health assessment (n = 7), requirement to share information on the prescription (n = 15), providing laboratory tests for baseline assessments (n = 2), and specification of the need to and process for monitoring of side effects specifically (n = 6). Table 5 provides a summary of all identified policies, indicating the setting for which the policy applied, and activities required to occur during the clinical encounter.

Vesting of Authority to Provide Informed Consent

All 23 states endorsed policies that designated an authority for consenting to psychotropic medication use among youth in child welfare custody. These policies varied in: (1) the authority who was designated, whether the youth or a surrogate decision-maker, (2) whether written documentation was required, and (3) whether youth were explicitly provided the right of refusal.

Figure 2 illustrates the multiple types of individuals vested with the authority to consent to psychotropic medication use across all states. First, some states vested decision-making authority among the individuals present at the clinical encounter with the prescriber, caregiver, and possibly youth participating in the informed consent process during the pediatric visit. In others, decision-making authority resided within the child welfare agency whether consenting authority was vested with the child welfare caseworker, supervisor, or an individual/unit with health and/or mental health expertise. Decision-making authority also resided external to the child welfare agency (e.g., the court system). Finally, some states vested the caregiver of origin with decision-making authority until reunification no longer remained a service plan goal. Variation also existed in the extent to which training, psychiatric consultation and decision aids were made available to those with consenting authority.

States endorsed informed consent policies that indicated a distinct set of surrogate decision-makers for youth in child welfare custody. As described in Appendix Table 2, states endorsed policies articulating who was vested with consenting authority, including the guardian (n = 16), the parent (n = 15), child welfare agency staff (n = 8), legal custodian (n = 5), the judicial system (n = 5), and the youth, themselves (n = 8). Notably, policies also commonly indicated the potential for multiple individuals to consent to the use of psychotropic medications for youth in child welfare custody rather than designating authority to a single individual alone. In some cases, the conditions under which the individual could consent to psychotropic medications use were well-formulated. For example, two states (PA, IL) articulate that all individuals vested with decision-making authority were required to provide consent for psychotropic medications. In other cases, policies clearly specified the conditions upon which the designated decision-maker could address psychotropic medication use. For example, the conditions upon which youth could provide consent were generally clearly specified (e.g., specification of an age and when developmentally appropriate). In other cases, policies articulated multiple individuals could serve as a surrogate decision-maker but did not specify fully the conditions upon which this was possible. There were also two cases in which were unable to assign a designated authority. Notably, in one state, the consenting authority in the policy denoted the “person legally responsible for psychiatric care” (NV). In a second state, the legislation identified a process by which courts would identify the surrogate decision-maker (TX). In these cases, the lack of specificity (NV) and potential variation of the designated authority (TX) prevented our ability to code the consenting authorities in the taxonomy.

As detailed in Table 6, policies also indicated, to varying extent, whether youth in child welfare custody held assenting authority for psychotropic medication use. Six states held policies that specified the right for all youth in child welfare custody to refuse psychotropic medication use. States also endorsed policies explicitly recognizing youth assent for psychotropic medication prescribing in specific contexts, specifically group homes (n = 3), residential treatment (n = 3) and out-of-home care (n = 1).

Supplemental analyses also investigated the number of procedural elements endorsed based on the consenting authority of the respective state policy. Analyses found minimal variation in the average number of procedural elements endorsed across consenting authorities, ranging from on average 2.6 procedural elements for states delegating consent to legal custodians to an average of 3.5 procedural elements for states delegating consenting authority to individuals not otherwise captured in our categorical list. (See Appendix Table 3.)

Notification of Consenting Decision to Stakeholders

Policies may also require that specific stakeholder be notified of the decision to authorize psychotropic medications. Requirements that those specific stakeholders were notified of the prescription were stated in ten policies across six states (including DC). As articulated in Table 6, policies ranged in both the specificity and breadth of individuals for whom notification was indicated, ranging from “all appropriate parties” to individuals specific to the child welfare system (e.g., Court Appointed Special Advocate, caseworker) to the parent, guardian, or the custodian.

Ongoing Review of Consent over Time

Specification that the consenting authority revisit the prior decision for authorization within a specified timeframe or under specific circumstances was present in nine policies across five states. Four of these five states had a policy for ongoing review that pertained to all youth in child welfare custody. Two states had policies that applied to those youth in child welfare custody who were in residential treatment settings and one state held a policy for ongoing review specific to psychiatric hospitals. As described in Table 6, these policies specified both timeframes and circumstances. The majority of policies (n = 8) indicated a timeframe for ongoing review, ranging from monthly (n = 1) to annually (n = 6). Of note, one state (OR) conditioned an ongoing annual review on specific prescribing practices, specifically highlighting the need for annual review when a child is prescribed two or more psychotropic medications concurrently or the child is under 6 years of age.

Discussion

This article identifies a taxonomy for the procedural elements of informed consent based upon existing child welfare policy and then assesses the extent to which these are codified in statutes or regulations that are publicly accessible. Specification of these procedural elements in formal policies is a critical aspect of promoting transparency and facilitating public discourse and legal protections for vulnerable populations, such as youth in child welfare custody (Noonan & Miller, 2013).

Drawing on key informant interviews with child welfare mid-level administrators, this study defines five procedural elements of existing policies governing informed consent for the administration of psychotropic medications to youth in child welfare custody, including: (1) information to be gathered about the child’s social and medical history, (2) activities required to inform the prescribing decision, (3) the individual vested with authority to consent to psychotropic medication use, (4) the process for notifying stakeholders of the prescription, and (5) parameters for ongoing review of the prior decision. Our review identified 23 states with legislation detailing some part of the informed consent process, but only two states specified all five of the procedural elements identified in the taxonomy. Moreover, the content of each procedural element varied across policies. For instance, while all states delineated the individual(s) authorized to consent (whether the youth or a surrogate decision-maker), variation existed to whom that responsibility was assigned across the states. Thus, while our taxonomy provides a framework for understanding and potentially creating policies around informed consent, there is still much to be understood about whether, how, and why each of these procedural elements for informed consent are specified and in what contexts.

The procedural elements of informed consent set requirements prior to the clinical encounter, during that encounter, and after the decision to authorize psychotropic medication use. That is, policies that include procedural elements prior to and following the consenting decision itself. This suggests an informed consent process requires an ongoing commitment, relying on information prior to the consenting decision, itself, and the ability to ensure ongoing review after the consenting decision has been made. Professional standards of care for youth in child welfare custody emphasize the need to gather both medical and social histories of youth in child welfare custody before providing medical and mental health care (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018). Consistent with these professional recommendations, our study reveals that formal policies do, in some cases, articulate the collection of social and medical history before the consenting decision occurs. Formal policies may also require revisiting the decision of consent throughout the duration of caring for the patient, which is consistent with professional standards for ongoing oversight of prescribed psychotropic medications. The need for ongoing monitoring warrants particular consideration given the limited data on long-term efficacy and potential side effects of psychotropic medication use among children and adolescents (Quinlan-Davidson et al., 2021). However, the absence of these procedural elements in many of the formal policies endorsing informed consent present represents a failure to leverage the potential of formal policies to facilitate compliance and accountability with standards of care (Noonan & Miller, 2013; Raghavan et al., 2008).

At the same time, the presented taxonomy of procedural elements in informed consent policies also fails to respond fully to calls for shared decision-making. Our taxonomy sought to capture procedural elements of informed consent policies in practice rather than in an ideal world. Determination of the latter is a critical next step for this work. For example, opportunities exist for the procedural elements of an informed consent process to highlight the agency and involvement of youth in every step of the process. Multiple stakeholders have articulated the necessity for youth to be provided with agency throughout the informed consent process and to hold decision-making authority for themselves, whenever possible (Simmel et al., 2021). Additionally, the quality of engagement could be more deeply conceptualized to facilitate multi-directional communication and education. For example, the final step of notification could be articulated as education to ensure that all relevant individuals, including the youth themselves, are not only notified but also educated about the treatment provided. Future work and expert consensus with youth in child welfare custody or alumni of the foster care system, caregivers of origin, caseworkers, foster parents, clinicians, among others is warranted to provide additional specification of a “patient- and stakeholder-centered” taxonomy for the procedural elements of an informed consent process for psychotropic medications for youth in child welfare custody. Such a taxonomy could be compared to the taxonomy presented in this paper to identify opportunities for greater alignment and improvement in current child welfare policy and practice.

All five procedural elements were not uniformly applied across states. The decisions at the state level to include or conversely not to include an element likely reflects legislators conceptualization of the goals and purposes of informed consent. While the child welfare system is charged with the three goals of safety, permanency, and well-being in the Adoption and Safe Families Act (1997), decisions about the informed consent process and surrogate decision-maker may reflect which of these goals is prioritized. For instance, states that include judicial oversight of prescribing decisions may be prioritizing the goal of safety and well-being while clinical review may be placing priority on the medical expertise specifically. In contrast, designation of decisional authority to the caregiver of origin demonstrates a commitment of the system to the goal of reunification and permanency. The variability identified in formal policies endorsing informed consent creates opportunities for confusion or gaps that may generate arbitrary decision-making. The variability in the presence and content of the procedural elements included in these formal policies is worth particular mention. For example, a prior systematic review emphasizes that youth in child welfare custody report experiencing inadequate engagement in the discussion of treatment alternatives and potential side effects (Barnett et al., 2019). Specification of these procedures at the time of prescribing in formal policies increases the potential not only for standardization but also legal protection.

Our findings also suggest that a single state may hold multiple formal policies in place to specify informed consent for psychotropic medication use among youth in child welfare custody. These policies specified different procedural elements of the informed consent process or specific sub-populations for which the policy articulated a specific process. This variation, on the one hand, provides opportunities for procedural elements to be integrated in other policy domains with valuable adaptations being provided to accommodate the wide array of placement settings youth in child welfare custody may have. At the same time, variation in the formal policies, if not clearly operationalized for child welfare and youth-serving partners, may create the possibility of confusion around the requirements to individuals (e.g., caseworkers, out-of-home treatment providers) critical in implementing the informed consent policy for youth in child welfare custody (Lipsky, 2010). Implementation of these formal policies fundamentally rely on a diverse array of individuals to implement them and their understanding and perception of formal policies regarding informed consent is a critical area to identify and address potential policy implementation challenges.

These findings could be used for policymakers to consider whether their policies align with the procedural elements endorsed in other child welfare settings. For instance, policymakers could examine these five elements when designing a policy to determine which are applicable to their particular case. Such guidance could assist policymakers in arriving at consensus on the procedural elements to include in development of their respective policies. Some elements specified for youth in child welfare custody may reflect the particular challenges that characterized informed decision-making. For example, the need to notify various individuals of the decision to prescribe psychotropic medications for youth in child welfare custody is especially important, given the number of individuals that are involved in the life of the youth and the transitions routinely experienced by these youth. In other cases, specification of the treatment administration, risks and benefits, and side effect protocols of a proposed treatment applies broadly for medical care and is consistent with standards of patient-centered care. At the same time, critical to design of informed consent policy would also be integration of the perspective of youth and other relevant community members from within their jurisdiction (e.g., caregivers, biological parents, caseworkers).

Notably, the National Academy of Medicine among others has made calls to encourage dialogue between physicians and patients in the decision-making process (Committee on Quality of Health Care in America & Institute of Medicine, 2001). These calls emphasize that patient-centered care, which is both respectful and responsive to the preferences, needs and values of the patient and their caregiver, should guide clinical decisions. As a principle of medical practice, patient-centered care emphasizes the need for dialogue around the relative merits of potential treatment alternatives in all medical care. Specific procedural elements, such as sharing information on the medication itself and providing youth the ability to consent or assent for the medications themselves, emphasize key elements of patient-centered care. However, other aspects of the policies identified, such as reliance on a consenting authority not at the clinical encounter, may challenge whether shared decision-making can occur without efforts to ensure responsiveness to the needs and values of the patient and their caregiver.

In addition, further examination of the policy-making process could help us understand how legislators consider the trade-offs that present themselves in specifying procedural elements of informed consent in policy. On the one hand, formal policy presents the benefit of generating transparency with regard to required procedural elements for informed consent providing opportunity for accountability in prescribing psychotropic medications. On the other hand, formal policy may present liabilities for the state system should they not comply with regulations. Obtaining procedural elements of informed consent may also provide the decisional support that caregivers of youth in child welfare custody indicate needing (Barnett et al., 2016a). For example, prior research suggests caregivers rely heavily on finding information about prescribed psychotropic medications themselves (Barnett et al., 2016b). Moreover, stakeholders including caregivers and caseworkers have highlighted the importance of those who know the child best centrally involved in decision-making; participation in clinical visits; the problems of delays in important treatment decisions when individuals authorized to consent are not immediately available; and the value of shared decision-making in an inclusive team approach (Simmel et al., 2021). On the other hand, stakeholders have also identified the potential value of a single external authority to provide objective oversight and guard against the hazards of overprescribing, inappropriate dosages, and polypharmacy (Simmel et al., 2021). These considerations highlight the complex trade-offs involved in achieving a process that achieves the tenets of shared decision-making with the desire to centralize decision-making authority with individuals offering the clinical expertise required to provide oversight of medication decisions. Future research is also needed to identify whether enactment of informed consent policies is effective in addressing concerns regarding safe and judicious use; no such studies were identified in a relevant systematic review of strategies to advance the safe and judicious use of antipsychotic medications (Mackie et al., 2020a, 2020b). Whether through formal or informal policies, opportunities exist for legislators and child welfare administrators to consider the commitments they hold to ensuring decisions that are both well-informed and in the best interests of the child.

Additionally, investigations into the factors influential to the development of and variation among state informed consent policies presents an important area for additional inquiry. Despite federal calls and coordinated technical assistance efforts to facilitate psychotropic medication oversight among youth in child welfare custody (Mackie et al., 2017, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018), substantial variation persists in the extent of state policy endorsement nationally. While prior research examines how states engaged evidence in “defining the problem of psychotropic medication use” (Hyde et al., 2016), additional research is warranted to investigate how informed consent policies emerged in response to these concerns and the role of evidence and relevant stakeholders in agenda setting and policy formulation. Such inquiry would provide important opportunity to identify potential opportunities to advance development of state policies that facilitate both transparency and accountability in the informed consent process implemented by child welfare agencies.

Limitations

Our review is a first step in the process of creating additional transparency in procedural elements currently endorsed by state legislation. The taxonomy, itself, represents the procedural elements of informed consent policies as articulated by mid-level administrators in public sector agencies. The data presented in this article do not reflect the perspectives from key stakeholders, including youth in or alumni of the child welfare system. Given the well-documented challenges to processes of meaningful informed consent and shared decision-making in child welfare settings, a critical next line of inquiry is whether these procedural elements adequately respond to the needs of youth and other key community partners. Opportunities also exist to ensure the procedural elements articulated in this paper are consistent with current practice. Therefore, future research is needed to determine whether procedural elements identified are consistent with contemporary child welfare practice and align with the priorities of key stakeholders, including youth.

Our initial set of interviews with mid-level administrators to establish the procedural elements of child welfare policies occurred in 2009–2010. This framework presented was triangulated methodologically with the legislative review conducted with data arriving from as recent as February 2022. The taxonomy developed in 2009–2010 served as a helpful framework to the organization of the data collated through the legislative review. Future research might investigate whether recent informal policies require an update and modification to the taxonomy of procedural elements endorsed by child welfare agencies.

Additionally, our review of statutes and regulations captures only a subset of the policies that may be endorsed by state or county child welfare agencies. Agencies may hold policies for informed consent that were implemented organizationally but are not legislatively mandated. It is also important to note that our analyses only sought to identify policies that specifically sought to indicate provisions for youth in child welfare custody; other policies may exist generally for youth placed in a variety of different settings. If these policies did not provide a specific provision for youth in child welfare custody, then we did not include these policies in the present analyses. Future research will be important to consider the informed consent policies in place more broadly for youth engaged in specific treatment settings, such as residential treatment settings, psychiatric hospitals, etc.

Conclusions

The present study identifies a taxonomy for the procedural elements of child welfare policies that endorse an informed consent process for psychotropic medications among youth in child welfare custody. The article subsequently identifies whether formal legislative policies across the 50 states and D.C. endorse these five procedural elements and characterizes the variation that exists. Only two states endorsed policies that included all five procedural elements and drastic variation characterized the content of these policies. This paper argues that additional specification in informed consent policies is needed to advance the opportunity for policy to promote professional standards of care and best practice. Opportunities also exist for future studies to consider the applicability of this framework in the context of other cases of informed consent, especially in cases of surrogate decision-making.

References

American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. (2012). A guide for community child serving agencies on psychotropic medications for children and adolescents. Retrieved from https://www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/docs/press/guide_for_community_child_serving_agencies_on_psychotropic_medications_for_children_and_adolescents_2012.pdf.

American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. (2015). Recommendations about the use of psychotropic medications for children and adolescents involved in ChildServing systems. Retrieved from https://www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/docs/clinical_practice_center/systems_of_care/AACAP_Psychotropic_Medication_Recommendations_2015_FINAL.pdf.

Barnett, E. R., Boucher, E. A., Neubacher, K., & Carpenter-Song, E. A. (2016a). Decision-making around psychotropic medications for children in foster care: Perspectives from foster parents. Children and Youth Services Review, 70, 206–213.

Barnett, E. R., Butcher, R. L., Neubacher, K., Jankowski, M. K., Daviss, W. B., Carluzzo, K. L., Ungarelli, E. G., & Yackley, C. R. (2016b). Psychotropic medications in child welfare: From federal mandate to direct care. Children and Youth Services Review, 66, 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.04.015

Barnett, E. R., Concepcion-Zayas, M. T., Zisman-Ilani, Y., & Bellonci, C. (2019). Patient-centered psychiatric care for youth in foster care: A systematic and critical review. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 13(4), 462–489.

Bertrand, J. T., Brown, J. E., & Ward, V. M. (1992). Techniques for analyzing focus group data. Evaluation Review, 16(2), 198–209.

Braithwaite, R. S., & Caplan, A. (2014). Does patient-centered care mean that informed consent is necessary for clinical performance measures? Journal of General Internal Medicine, 29(4), 558–559.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101.

Chen, S., Barner, J. C., & Cho, E. (2021). Trends in off-label use of antipsychotic medications among Texas Medicaid children and adolescents from 2013 to 2016. Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy, 27(8), 1035–1045.

Child and Family Services Improvement and Innovation Act of 2011, P.L. pp. 112–134. (2011).

Christian, R. B., Farley, J. F., Sheitman, B., et al. (2013). A+KIDS, a web-based antipsychotic registry for North Carolina youth: An alternative to prior authorization. Psychiatric Services, 64(9), 893–900.

Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, & Institute of Medicine. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. National Academy Press.

Crystal, S., Mackie, T. I., Fenton, M. C., Amin, S., Neese-Todd, S., Olfson, M., & Bilder, S. (2016). Rapid growth of antipsychotic prescriptions for children who are publicly insured has ceased, but concerns remain. Health Affairs, 35(6), 974–982.

Crystal, S., Olfson, M., Huang, C., Pincus, H., & Gerhard, T. (2009). Broadened use of atypical antipsychotics: Safety, effectiveness, and policy challenges. Health Affairs (millwood), 28(5), w770–w781.

Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act of 2008, P.L. pp. 110–351. (2008).

Ginsberg, M. D. (2010). Informed consent: no longer just what the doctor ordered-the contributions of medical associations and courts to a more patient friendly doctrine. Michigan State University Journal of Medicine and Law, 15, 17.

Government Accountability Office. (2011). Foster children: HHS guidance could help states improve oversight of psychotropic prescriptions. Retrieved from Washington, DC http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d12270t.pdf.

Government Accountability Office. (2017). Foster children: HHS has taken steps to support states’ oversight of psychotropic medication, but additional assistance could further collaboration. Retrieved from Washington, DC https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-17-129.pdf.

Hall, D. E., Prochazka, A. V., & Fink, A. S. (2012). Informed consent for clinical treatment. CMAJ, 184(5), 533–540.

Hyde, J. K., Mackie, T. I., Palinkas, L. A., Niemi, E., & Leslie, L. K. (2016). Evidence use in mental health policy making for children in foster care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(1), 52–66.

Katz, A. L., & Webb, S. A. (2016). Informed consent in decision-making in pediatric practice. Pediatrics (evanston), 138(2), e20161485. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1485

Lipsky, M. (2010). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public service. Russell Sage Foundation.

Mackie, T. I., Cook, S., Crystal, S., Olfson, M., & Akincigil, A. (2020a). Antipsychotic use among youth in foster care enrolled in a specialized managed care organization intervention. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(1), 166–176.

Mackie, T., Hyde, J., Palinkas, L. A., Niemi, E., & Leslie, L. K. (2017). Fostering psychotropic medication oversight for children in foster care: A national examination of states’ monitoring mechanisms. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 44(2), 243–257.

Mackie, T. I., Schaefer, A. J., Karpman, H. E., Lee, S. M., Bellonci, C., & Larson, J. (2020b). Systematic review: Systemwide interventions to monitor pediatric antipsychotic prescribing and promote best practice. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.08.441

Mosca, L., Linfante, A. H., Benjamin, E. J., Berra, K., Hayes, S. N., Walsh, B. W., Fabunmi, R. P., Kwan, J., Mills, T., & Simpson, S. L. (2005). National study of physician awareness and adherence to cardiovascular disease prevention guidelines. Circulation, 111(4), 499–510. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000154568.43333.82

Naylor, M. W., Davidson, C. V., Ortega-Piron, D. J., Bass, A., Gutierrez, A., & Hall, A. (2007). Psychotropic medication management for youth in state care: Consent, oversight, and policy considerations. Child Welfare, 86(5), 175–192.

Noonan, K., & Miller, D. J. H. L. (2013). Fostering transparency: A preliminary review of policy governing psychotropic medications in foster care. Hasting LJ, 65, 1515.

Oppenheim, E., Lee, R., Lichtenstein, C., Bledsoe, K. L., & Fisher, S. K. (2012). Reforming mental health services for children in foster care: The role of child welfare class action lawsuits and systems of care. Families in Society, 93(4), 287–294.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (Vol. 3). Sage.

Quinlan-Davidson, M., Roberts, K. J., Devakumar, D., Sawyer, S. M., Cortez, R., & Kiss, L. (2021). Evaluating quality in adolescent mental health services: A systematic review. British Medical Journal Open, 11(5), e044929.

Raghavan, R., Bright, C. L., & Shadoin, A. L. (2008). Toward a policy ecology of implementation of evidence-based practices in public mental health settings. Implementation Science, 3(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-3-26

Rinfret, S. R., Scheberle, D., & Pautz, M. C. (2018). Public policy: A concise introduction. CQ Press.

Simmel, C., Bowden, C. F., Neese-Todd, S., Hyde, J., & Crystal, S. (2021). Antipsychotic treatment for youth in foster care: Perspectives on improving youths’ experiences in providing informed consent. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 91(2), 258.

Srivastava, A., & Thomson, S. B. (2009). Framework analysis: a qualitative methodology for applied policy research.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018). Guidance on strategies to promote best practice in antipsychotic prescribing for children and adolescents. HHS Publication No. PEP19‐ ANTIPSYCHOTIC‐BP. Rockville, MD: Office of Chief Medical Officer.

The Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997, P.L. pp. 105–189. (1997).

Acknowledgements

The authors would also like to acknowledge the assistance of Erick Rojas, JD, MPH, who made contributions while employed at the Institute for Health, Health Care Policy and Aging at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey.

Funding

Research reported in this article was funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute® (PCORI®) Award (IHS-1409-23194), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ; 1R36 HS02198501, 1R01HS026001), W.T. Grant Foundation (PI: Laurel K. Leslie), and National Center for Advancing Clinical and Translational Sciences at the National Institute of Health (UL1TR003017). The views presented in this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute® (PCORI®), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the W.T. Grant Foundation nor the National Institute of Health. The authors also declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TM, LL, and SC were responsible for study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by TM, AS, and LL. The first draft of the manuscript was written by TM, HK, JP, and AS and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained from the [academic institution withheld to preserve anonymity of authors].

Informed Consent

All participants provided written informed consent for participation and publication after receiving a complete description of the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mackie, T.I., Schaefer, A.J., Palatucci, J.S. et al. The Role of Formal Policy to Promote Informed Consent of Psychotropic Medications for Youth in Child Welfare Custody: A National Examination. Adm Policy Ment Health 49, 986–1003 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-022-01212-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-022-01212-3