Abstract

The influence of surface anisotropy upon the near-wall region of a rough-wall turbulent channel flow is investigated using direct numerical simulation (DNS). A set of nine irregular rough surfaces with fixed mean peak-to-valley height, near-Gaussian height distributions and specified streamwise and spanwise correlation lengths were synthesised using a surface generation algorithm. By defining the surface anisotropy ratio (SAR) as the ratio of the streamwise and spanwise correlation lengths of the surface, we demonstrate that surfaces with a strong spanwise anisotropy (SAR < 1) can induce an over 200% increase in the roughness function ΔU+, compared to their streamwise anisotropic (SAR > 1) equivalent. Furthermore, we find that the relationship between the roughness function ΔU+ and the SAR parameter approximately follows an exponentially decaying function. The statistical response of the near-wall flow is studied using a “double-averaging” methodology in order to distinguish form-induced “dispersive” stresses from their turbulent counterparts. Outer-layer similarity is recovered for the mean velocity defect profile as well as the Reynolds stresses. The dispersive stresses all attain their maxima within the roughness canopy. Only the streamwise dispersive stress reaches levels that are comparable to the equivalent Reynolds stress, with surfaces of high SAR attaining the highest levels of streamwise dispersive stress. The Reynolds stress anisotropy also shows distinct differences between cases with strong streamwise anisotropy that stay close to an axisymmetric, rod-like state for all wall-normal locations, compared to cases with spanwise anisotropy where an axisymmetric, disk-like state of the Reynolds stress anisotropy tensor is observed around the roughness mean plane. Overall, the results from this study underline that the drag penalty incurred by a rough surface is strongly influenced by the surface topography and highlight its impact upon the mean momentum deficit in the outer flow as well as the Reynolds and dispersive stresses within the roughness layer.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Many forms of irregular roughness found on engineering surfaces display some degree of anisotropy. For example, production processes, such as milling, generate irregular surfaces with a “lay” that represents the direction of predominant surface patterns [1]. Anisotropic roughness is also encountered on in-service turbine vanes [2], bio-fouled ship hulls [3] and can often be observed in geo- and astrophysical contexts, e.g. in the form of ripple-patterns, which for example affect sand-transporting winds on Mars [4]. Another form of anisotropic irregular roughness are ocean waves that can act as roughness elements on the atmosphere [5, 6]. As a result, the fluid dynamic properties of anisotropic forms of roughness are of wide practical interest.

The drag penalty incurred by a rough surface depends on the characteristic height of the roughness features, but is also strongly influenced by the roughness topography. In a study based on surface scans, Thakkar et al. [7] identified the streamwise correlation length of the roughness as one of the key topographical parameters that influence the roughness function. Traditionally, the influence of roughness correlation length has mostly been studied for the case of regular bar-type roughness. Perry et al. [8] showed experimentally that the spacing distance between transverse bars, i.e. the effective streamwise correlation length of the surface, has a strong effect on the observed roughness effect, with short spacing giving rise to d-type behaviour and longer spacing inducing k-type behaviour. In the direct numerical simulations (DNS) of Leonardi et al. [9], the spacing of bars was shown to affect the coherence of the near-wall flow as well as the levels of turbulence anisotropy. Another widely studied form of regular anisotropic roughness are wavy walls. For example, in the experimental study of Hamed et al. [10] fundamental differences for flow over two- and three-dimensional large-scale wavy walls were found that have practical implications for bed erosion and sediment transport.

In a recent study of turbulent flow in sinusoidal, spanwise-periodic channels, Vidal et al. [11] found strong interaction between opposite walls when the wave-length of the roughness was of the same order of magnitude as the half height as the channel. For smaller wavelengths, the size of secondary vortices was reduced, but significant cross-flow could still be observed. When the inner-scaled wave-length dropped below λ+ = 130 the cross-flow decayed. While flow over streamwise aligned bars has also been investigated (see e.g. [12, 13]), the most widely studied type of strongly streamwise anisotropic roughness are riblet surfaces that have been inspired by the shark-skin effect [14, 15]. Riblets typically consist of closely spaced structures, such as triangular grooves or blades, in the cross-stream direction that are uniform in the streamwise direction of the flow [16]. The unique characteristic of riblets is that they induce a drag reduction instead of a drag increase for a range of Reynolds numbers determined by the square-root of the groove cross-section of the riblets [17, 18].

Rough surfaces in engineering or in the natural environment are often irregular, i.e., they do not follow a simple, regular pattern as the man-made bar, riblet, or sinusoidal surfaces discussed above. The investigation of flow over irregular roughness has received increased attention in recent years. In most cases, the investigated surfaces were nearly isotropic and the influence of anisotropy has not been considered as the focus of the studies was typically on specific examples of roughness of technical importance or on other topographical parameters such as the skewness of the height distribution. For example, Yuan & Piomelli [19] used large-eddy simulations to investigate flow over artificial sand-paper roughness and rough surfaces replicated from turbine blades. Busse et al. [20] investigated the Reynolds number dependence of turbulent flow over a grit-blasted and a graphite surface using direct numerical simulation. Forooghi et al. [21] created systematically varied isotropic, irregular roughness using random arrangements of roughness elements to investigate the effect of topographical parameters on mean flow and turbulence statistics. Barros et al. [22] used systematically generated isotropic irregular roughness in experiments of turbulent channel flow to study the influence of the power-law slope of a rough surface and showed that the roughness effect decreases with increasing power-law slope.

A mildly anisotropic irregular roughness that has been the subject of several experimental investigations is a surface measured by Bons et al. [2] for a damaged turbine blade. Wu and Christensen [23] studied the spatial structure of a turbulent boundary layer above a replica of this surface and noted an attenuation of the streamwise coherence of the near-wall flow. In a related study, Barros and Christensen [24] reported turbulent secondary flows induced by spanwise heterogeneities over the same turbine blade roughness. However, the influence of the degree of spanwise heterogeneity, i.e. spanwise correlation length, remained unclear, as only a single roughness specimen was considered.

The objective of this study is to systematically investigate the impact of the degree of surface anisotropy upon the near-wall region of rough-wall turbulent channel flow. To this end, DNS of turbulent channel flow over a set of synthetically generated irregular rough surfaces with specified streamwise and spanwise correlation lengths have been performed. In Section 2, the surface generation procedure is described and an overview of the investigated surface topographies is given. Section 3 summarises the numerical approach taken in the DNS of turbulent channel flow and the triple decomposition applied to the velocity field. Results for the mean flow and turbulence statistics are presented in Section 4. Summary and conclusions follow in Section 5.

2 Surface Generation and Topographical Characterisation

Surface height maps were generated by taking linear combinations of Gaussian random number matrices using a moving average (MA) process. This method of surface generation was developed by Patir [25] and has been extended here with periodic boundaries. A periodic Gaussian heightmap, hij, was generated by taking the linear transformation

where ηij is an N × M matrix of uncorrelated random numbers with a Gaussian distribution, αkl are an n × m set of weights that give a user-specified autocorrelation coefficient function (ACF) and mod is the modulo operator.

The weights of the MA process, αkl, are determined by solving the non-linear system

using the Newton method outlined by Patir [25], where Rpq is the discrete ACF. Each Gaussian height map is generated with an exponential ACF

where \(\left ({\varDelta }{x}^{}_{1},{\varDelta }{x}^{}_{2}\right )\) denote the spatial separations in the streamwise and spanwise directions, respectively, and where \(\left ({\varDelta }{x}^{*}_{1},{\varDelta }{x}^{*}_{2}\right )\) denote the spatial separations at which the streamwise and spanwise ACF profiles decay to 10% of their values at the origin. Further details can be found in the work of Patir [25].

Using the above method, a set of Gaussian height maps with systematically varied correlation lengths were generated. In total, eight anisotropic surfaces and one isotropic surface were synthesised. A set of smoothly varying topographies were obtained by passing each discrete heightmap through a low-pass Fourier filter [26]. The anisotropy of each filtered heightmap was quantified using the surface anisotropy ratio (SAR) defined here as

where \({\mathcal{L}}_{x}\) and \({\mathcal{L}}_{y}\) denote the streamwise and spanwise correlation lengths, respectively. Correlation lengths were computed based on a 0.2 cutoff criterion in order to be consistent with past work related to the current study [7] and general conventions used in surface metrology [27]. The final surfaces that were applied in the DNS are shown in Fig. 1.

For the nine surfaces considered in this study, SAR ranges from ≈ 1/18 to ≈ 16. All surfaces were synthesised with a near-Gaussian height distribution, i.e. with negligible skewness \(\left (Ssk\approx 0\right )\) and kurtosis approximately equal to three \(\left (Sku\approx 3\right )\). This allows the current study to focus on the effect of surface correlation length, since skewness and kurtosis have been effectively eliminated as parameters. Topographical parameters are given in Tables 1 and 2, for full definitions the reader is referred to [7, 27]. The peaks of an irregular rough surface make the strongest contributions to its fluid dynamic roughness effect [28]. As can be observed from Fig. 1, the cases with SAR > 1 are dominated by streamwise elongated peaks whereas the surfaces with SAR < 1 display spanwise elongated peaks.

In the current study, the minimum typical roughness feature size, i.e. \(\min \limits ({\mathcal{L}}_{x},{\mathcal{L}}_{y})\), was kept constant to ≈ 0.1δ to make the surface anisotropy ratio SAR the key parameter. The streamwise effective slope

where h(x1,x2) is the surface height and L1 and L2 are the domain size in the streamwise and spanwise direction, was first introduced by Napoli et al. [29]. As can be observed from Table 2 and Fig. 2a, the streamwise effective slope ESx is influenced by both the streamwise and the spanwise correlation length. For constant streamwise correlation length, i.e. the cases with SAR < 1, the streamwise effective slope ESx increases with increasing spanwise correlation length. For constant spanwise correlation length (SAR > 1), ESx decays with increasing streamwise correlation length. Overall, an approximately exponential decay of ESx with the surface anisotropy ratio can be observed (\(ES_{x}\sim \exp (-{\text {SAR}}))\). The spanwise effective slope ESy,

follows exactly the opposite trends. Therefore, to maintain a constant effective slope for increasing streamwise correlation length, the spanwise correlation would have to be decreased for a given SAR; this would incur a decrease in the minimum feature size of the surface with increasing streamwise correlation length (i.e. effectively narrower and narrower ribs) counter to the aims of this study. A further observation for the relation between SAR and effective slope is that the the ratio of streamwise to spanwise effective slope ESx/ESy, shown in Fig. 2b, follows a decay with approximately SAR− 1/2 for the generated surfaces. The relatively slow decay of this ratio with SAR can be attributed to the stronger influence of the high wavenumber content of a surface on the effective slope compared to its effect on the correlation length in the corresponding direction.

The SAR parameter is also related to the surface texture aspect ratio Str, a parameter for characterisation of surface anisotropy widely used in tribology [27, 30]. Str is defined as the ratio of the shortest to the longest correlation length based on the central lobe of the 2D surface height autocorrelation function. For the given surfaces, Str attains its minima for the cases with the maximum streamwise or spanwise correlation length (see Table 2). However, Str does not contain any information about the orientation of the anisotropy with respect to the mean flow direction, which is why SAR will be used throughout this study as parameter for quantifying surface anisotropy.

3 Numerical Setup and Averaging Methods

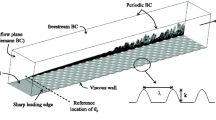

For each surface listed in Table 1, a DNS of incompressible turbulent channel flow with roughness on both the top and bottom walls and periodic boundary conditions in the streamwise and spanwise directions was performed. Second order central differences were used for the spatial discretisation of the Navier-Stokes equations; for the discretisation in time the second order Adams-Bashforth scheme was used. For the resolution of the irregular rough walls an iterative embedded-boundary method based on the algorithm by Yang & Balaras [31] was employed. Full details and validation of the numerical approach can be found in Busse et al. [26]. A reference smooth-wall simulation was also performed for comparison.

The flow was driven by a constant (negative) mean streamwise pressure gradient, π, which can be used to define the mean friction velocity as \(u_{\tau }\equiv \sqrt {\left (-{\delta }/{\rho }\right )\varPi }\) [32] where δ denotes the mean channel half-height and ρ is the density. The friction Reynolds number is defined here as Reτ ≡ uτδ/ν, where ν is the kinematic viscosity. All simulations in this study were carried out at a fixed friction Reynolds number of Reτ = 395.

Throughout this work, the Cartesian velocity components, \(u_{i}=\left (u_{1},u_{2},u_{3}\right )\), are aligned along their respective Cartesian coordinates, \(x_{i}=\left (x_{1},x_{2},x_{3}\right )\), where x1 is the streamwise, x2 the spanwise and x3 the wall-normal direction. In all cases, the domain size in the streamwise (L1) and spanwise (L2) direction is at least five times the corresponding correlation length of the surface. For cases with a surface anisotropy ratio between 1/8 ≤SAR ≤ 8 the “standard” domain size listed in Table 3 was used. For the two cases with the most extreme SAR values, i.e. SAR ≈ 1/18 and 16, larger domain sizes were applied to ensure that the irregular rough surfaces decorrelate over the width and length of the computational domain. Uniform mesh spacing with \({\Delta } x_{1}^{+} <5\) and \({\Delta } x_{2}^{+} <5\) was prescribed in the streamwise and spanwise directions for all rough-wall cases following standard resolution criteria [26]. In the wall-normal direction, uniform spacing with \({\varDelta } x^{+}_{3,\min \limits }\) was maintained in the roughness layer \(\min \limits (h)< x_{3} < \max \limits (h)\) and a gradual stretching was applied above with a maximum wall-normal grid spacing of \({\varDelta } x_{3,\max \limits }^{+}\) reached at the channel centre.

In this study, a double-averaging (DA) methodology following Raupach & Shaw [33] is used. This decomposes an instantaneous field variable, e.g. a component of the velocity ui, as

where \(\left <\overline {u}_{i}\right >\) is the DA part of ui, \(\tilde {u}_{i}\) is the form-induced “dispersive” spatial variation and \(u_{i}^{\prime }\) is the turbulent fluctuation about the local time-averaged mean of ui. The DA operator is defined here as

Here, \(\psi =A_{f}/\left (L_{1}L_{2}\right )\) is ratio of the fluid-occupied area, Af, to the total area L1L2 of a given horizontal plane x3 = const., i.e. in Eq. 8 the intrinsic average is used. The overbar is used to indicate the time-average. All time-averaged quantities have been averaged over a period of \(T^{+}=Tu_{\tau }^{2}/\nu >1.5\times 10^{4}\) in viscous units corresponding to a minimum averaging period of 50Tf where Tf = L1/Ub is the flow-through time based on the bulk-flow velocity. The averaging periods are comparable to the averaging periods employed in previous studies of flow over rough surfaces [21, 34] and thus the results can be considered well-converged. Above the highest roughness crest ψ = 1, whereas below the highest roughness crest, ψ becomes less than one \(\left (x_{3}<h_{\max \limits }\right )\). In solid-occupied regions all field variables are set to zero (\(u_{i}\left (\mathbf {x},t\right )=0\)).

Throughout this work, the roughness function, ΔU+, is defined as

where subscripts “cl”, “s” and “r” denote centre-line, smooth- and rough-wall quantities, respectively.

The components of the Reynolds stress tensor, \(\left < \overline {u_{i}^{\prime } u_{j}^{\prime }}\right >\), are based on the turbulent fluctations of the velocity field around the local mean

Similarly, the components of the dispersive stress tensor, \(\left \langle \tilde {u}_{i}\tilde {u}_{j}\right \rangle \) , are defined as

4 Results and Discussion

In this section, first the roughness function and the mean flow statistics are presented. This is followed by a discussion of the Reynolds and dispersive stress statistics. The flow statistics are then further discussed in the context of visualisations of the local streamwise and spanwise dispersive and Reynolds stresses within the roughness canopy. In the final part of this section, the influence of surface anisotropy on the anisotropy of the Reynolds stress tensor is explored using the Lumley triangle.

4.1 Roughness function

The roughness function ΔU+ is plotted as a function of the SAR parameter (4) in Fig. 3. A striking observation based on this data is that ΔU+ exhibits an over 200% increase as SAR is decreased from ≈ 16 to 1/8 (see Table 4). Considering that all surfaces have been scaled to an identical mean peak-to-valley height and share near-Gaussian height distributions (see Table 1), the sharp rise in ΔU+ underlines the impact that surface anisotropy can have upon the drag penalty incurred by a rough surface. For the case with SAR ≈ 1/18 a small drop in the roughness function compared to the S18 and S14 cases can be observed. This shows that once a high spanwise correlation of the surface is attained, a further increase of the spanwise surface correlation does not necessarily increase the roughness effect of a surface further. The small drop in ΔU+ for S118 compared to S18 by ≈ 4% could be attributed to an increased tendency of the flow to skim past the very wide spanwise peaks of the S118 surface compared to the circumnavigation of roughness peaks observed for surfaces with higher SAR (see below). Another contributing factor leading to a lower ΔU+ may be the small difference in Ssk of the two surfaces (see Table 1), as negative skewness is known to lower the roughness effect of a surface [28, 37].

a The roughness function, ΔU+, plotted as a function of the SAR parameter. An exponential behaviour (12) has been fitted to the data  . bΔU+ plotted as a function of the streamwise effective slope ESx. Data from the numerical studies of Napoli et al. [29] and De Marchis et al. [35] and the experimental study of Schultz & Flack [36] is included for comparison. Blue symbols are used for cases with SAR < 1 and red symbols for cases with SAR > 1 (see Table 1)

. bΔU+ plotted as a function of the streamwise effective slope ESx. Data from the numerical studies of Napoli et al. [29] and De Marchis et al. [35] and the experimental study of Schultz & Flack [36] is included for comparison. Blue symbols are used for cases with SAR < 1 and red symbols for cases with SAR > 1 (see Table 1)

The relationship between ΔU+ and the SAR parameter shown in Fig. 3 can be approximated by an exponential function of the form

where the coefficients \(\left \{b_{1},b_{2},b_{3}\right \}=\left \{2.35,5.33,0.207\right \}\) have been fitted to the model function using non-linear regression. Using Eq. 12, the roughness function is predicted to obtain a minimum value of ΔU+ ≈ 2.35 as \(\text {SAR}\rightarrow \infty \) and a maximum value of ΔU+ ≈ 7.68 as \(\text {SAR}\rightarrow 0\). However, this does not take into account the observed small decrease for very low surface anisotropy ratio.

Thakkar et al. [7] identified \({\mathcal{L}}_{x}\) as one of the key topographical parameters influencing the roughness function based on data obtained from DNS over a range of rough surfaces based on surface scans. The numerically generated irregular rough surfaces of the current study allow a more systematic probing of the influence of the correlation length. The strong decrease in ΔU+ with increasing SAR > 1 confirms the findings of Thakkar et al. regarding \({\mathcal{L}}_{x}\). Based on the current results we can in addition show that \({\mathcal{L}}_{y}\) also affects the roughness function as shown by the increase of ΔU+ with decreasing SAR < 1. However, with reference to Fig. 3, it is clear that the streamwise correlation length \({\mathcal{L}}_{x}\) of a surface has considerably stronger influence on the fluid dynamic roughness effect than its spanwise correlation length \({\mathcal{L}}_{y}\).

In Fig. 3b, the dependence of ΔU+ on the streamwise effective slope ESx is shown. For comparison, data from the numerical investigations of Napoli et al. [29] and De Marchis et al. [35] (irregular sinusoidal surfaces with infinite spanwise correlation) and the experimental investigations of Schultz & Flack [36] (regular pyramid-shaped roughness) are included. As expected, ΔU+ increases rapidly with effective slope for low values of ESx. For the higher effective slope cases, the attained roughness function values are lower in comparison to the reference data by Napoli et al. [29]. Several causes may contribute to the observed differences: In the current study, the roughness height measures are kept to close to constant values with, e.g., Sa ≈ 0.023δ for all cases, simulations were conducted at constant Reτ, and all surfaces have nearly zero skewness. While Napoli et al. also conducted their simulations at constant Reτ, they varied the roughness height Sa between different surfaces. For example, in the “First series” in [29] the roughness height was increased to increase the effective slope with the highest effective slope case attaining Sa ≈ 0.072δ, i.e., a significantly higher value than for the surfaces studied here. In the experimental study by Schultz & Flack [36] the Reynolds number was varied to attain fully rough behaviour. Furthermore, pyramid roughness has positive skewness Ssk. As ΔU+ is known to increase with Ssk [28, 37], the current study should yield lower ΔU+ values than the surfaces studied by Schultz & Flack as all surfaces have close to zero skewness.

4.2 Mean velocity profile

Wall-normal profiles of the DA streamwise velocity normalised by the friction velocity are plotted in Fig. 4. As the SAR parameter increases, the downward shift of the log-law decreases – indicating that spanwise anisotropic surfaces induce the largest rise in the mean momentum deficit. The differences in the mean velocity profiles for the cases with SAR < 1 are relatively small. In contrast, much higher differences in the mean streamwise velocity profiles can be observed for the cases with SAR > 1 in the log-law region above the roughness. Below the highest roughness crest \(\left (x_{3}<h_{\max \limits }\right )\), a DA reverse flow forms within the canopy of each surface (see inset of Fig. 4a). Whilst the shape and strength of the reverse flow region is strongly affected by the levels of streamwise anisotropy \(\left (\text {SAR}>1\right )\), a relative insensitivity is observed for the spanwise anisotropic surfaces \(\left (\text {SAR}<1\right )\).

a Mean streamwise velocity profiles. Line-types are given in Table 1. Smooth wall data \(\left (\circ \right )\) is also included. The smooth-wall viscous sublayer, \(\left <\overline {u}_{1}\right >^{+}= x_{3}^{+}\), and the log-law, \(\left <\overline {u}_{1}\right >^{+}=\kappa ^{-1}\ln x_{3}^{+}+B\), with κ = 0.41 and B = 5.5, are also plotted  . b Velocity-defect profiles. Line-types are given in Table 1. Smooth wall data \(\left (\circ \right )\) is also included. The approximate location of the highest roughness crests is indicated by a vertical dotted line

. b Velocity-defect profiles. Line-types are given in Table 1. Smooth wall data \(\left (\circ \right )\) is also included. The approximate location of the highest roughness crests is indicated by a vertical dotted line  at x3/δ = 0.11

at x3/δ = 0.11

Wall-normal profiles of the DA streamwise velocity-defect normalised by the friction velocity are shown in Fig. 4b. Above the highest roughness crest \(\left (x_{3}>h_{\max \limits }\right )\), a very close collapse between the smooth- and rough-wall data is observed indicating similarity in the outer layer mean flow. These results provide evidence for Townsend’s outer similarity hypothesis [38] and agree with the findings of past numerical [20] and experimental [39, 40] studies.

4.3 Reynolds and dispersive stresses

Wall-normal profiles of the streamwise normal Reynolds stress, \(\left < \overline {u_{1}^{\prime } u_{1}^{\prime }}\right >\) (10), normalised by the square of the friction velocity are plotted Fig. 5a. The smooth- and rough-wall profiles collapse in the outer region (see inset plot) and, with reference to the data shown previously in Fig. 4b, provide additional evidence for Townsend’s outer similarity hypothesis. For each surface considered in this study, the maximum \(\left < \overline {u_{1}^{\prime } u_{1}^{\prime }}\right >\) occurs below the highest roughness crest and exhibits a significant suppression relative to the smooth-wall value. An attenuation of the peak value of \(\left < \overline {u_{1}^{\prime } u_{1}^{\prime }}\right >\) in the presence of surface roughness can be interpreted as a disruption of the near-wall turbulence cycle [41]. Considering that the suppression of peak \(\left < \overline {u_{1}^{\prime } u_{1}^{\prime }}\right >\) increases as SAR decreases (see Fig. 5a), the current results imply that spanwise anisotropic surfaces are more effective at interrupting the near-wall streaks and quasi-streamwise vortices. For surface S118 a slight increase of the near-wall streamwise Reynolds can be observed, which is consistent with the slight higher ΔU+ value for this case compared to S18 and S14. Finally, we note that appreciable levels of \(\left < \overline {u_{1}^{\prime } u_{1}^{\prime }}\right >\) persist deep within the roughness canopy of each surface and that streamwise turbulence activity is promoted with increasing SAR. This trend agrees well the past results of Thakkar et al. [7], who noted elevated turbulence kinetic energy (TKE) levels below the highest peak of an irregular surface with SAR ≈ 30, relative to a surface with SAR ≈ 1/30.

a Streamwise normal Reynolds stresses; b streamwise normal dispersive stresses. Line-types are given in Table 1. Smooth wall data \(\left (\circ \right )\) is also included for the Reynolds stress. The approximate location of the highest roughness crests is indicated by a vertical dotted line  at x3/δ = 0.11

at x3/δ = 0.11

Wall-normal profiles of the streamwise dispersive fluctuations, \(\left <\tilde {u}_{1}\tilde {u}_{1}\right >\) (11), normalised by the square of the friction velocity are shown in Fig. 5b. Above the highest roughness crest \(\left (x_{3}>h_{\max \limits }\right )\), the magnitude of \(\left <\tilde {u}_{1}\tilde {u}_{1}\right >\) quickly drops to close to zero (see Fig. 5a) and shows no obvious dependence upon the SAR parameter. In contrast, below the highest roughness crest, the magnitudes of \(\left <\tilde {u}_{1}\tilde {u}_{1}\right >\) and \(\left < \overline {u_{1}^{\prime } u_{1}^{\prime }}\right >\) become comparable as a result of increasing spatial heterogeneity in the time-averaged flow. Comparing the \(\left <\tilde {u}_{1}\tilde {u}_{1}\right >\) profiles, it is clear that greater heterogeneity prevails within the canopies of streamwise anisotropic rough surfaces where the peak value \(\left <\tilde {u}_{1}\tilde {u}_{1}\right >\) increases with SAR and exceeds the streamwise Reynolds stresses for cases S41, S81, and S161. In contrast, approximately constant levels of \(\left <\tilde {u}_{1}\tilde {u}_{1}\right >\) can be observed for spanwise anisotropic surfaces (SAR ≤ 1). One possible explanation for this behaviour is a “streamwise-channeling” effect whereby regions of high-speed time-averaged streamwise velocity (i.e. high relative to the local DA value) are free to develop within the elongated cavities of streamwise anisotropic surfaces. Such channeling mechanisms may not occur in the case of spanwise anisotropic surfaces since the flow is more likely to be diverted to the spanwise direction to circumnavigate the peaks or to “skim” past the closely-spaced roughness cavities in a d-type manner [8]. For urban type roughness, similar channeling and skimming flow regimes have been observed (see e.g. [42]) and can have a strong effect on the urban microclimate [43].

The spanwise normal Reynolds stress \(\left < \overline {u_{2}^{\prime } u_{2}^{\prime }}\right >\), shown in Fig. 6a, is unlike \(\left < \overline {u_{1}^{\prime } u_{1}^{\prime }}\right >\) not strongly reduced in magnitude compared to the smooth-wall case in the roughness layer. For all rough cases, the peak value is attained around the highest roughness peak. For the isotropic surface, the level of \(\left < \overline {u_{2}^{\prime } u_{2}^{\prime }}\right >\) closely matches the smooth-wall values except for wall-normal locations that are within the deeper parts of the rough surface.

a Spanwise normal Reynolds stresses; b spanwise normal dispersive stresses. Line-types are given in Table 1. Smooth wall data \(\left (\circ \right )\) is also included for the Reynolds stress. The approximate location of the highest roughness crests is indicated by a vertical dotted line  at x3/δ = 0.11

at x3/δ = 0.11

For the spanwise anisotropic surfaces with SAR < 1 the peak value occurs just below \(h_{\max \limits }\) and exceeds the peak-value for the smooth wall case; this could be attributed to the higher spanwise disturbances induced in the flow field by the spanwise elongated peaks that are typical for the SAR < 1 cases (see Fig. 1), forcing the flow to circumnavigate wider obstacles close to the crest height compared to the cases with SAR ≥ 1. For regular transverse bar roughness, an increase in the peak value has been reported both for the DNS of Leonardi et al. [9] for bars with long spacings and for the DNS of Orlandi & Leonardi for bars with short spacings [12], which is consistent with the observations for the current irregular, spanwise anisotropic surfaces.

A reduction in the peak value compared to the smooth-wall and the isotropic rough case can be observed in the strongly streamwise anisotropic cases S81 and S161, with the strongest reduction occuring for case S161. For this case and the neighbouring case S81 the peak location occurs above the rough surface. The level of reduction is of similar magnitude as the reduction of spanwise velocity fluctuations that has been observed for riblets [15]. Above the rough surface, all profiles soon collapse on the profile for the smooth-wall reference case indicating that outer-layer similarity is recovered for the spanwise normal Reynolds stress.

Whereas the streamwise normal dispersive stress \(\left <\tilde {u}_{1}\tilde {u}_{1}\right >\) for some surfaces exceeds the peak level of the corresponding Reynolds stress, the spanwise normal dispersive stress \(\left <\tilde {u}_{2}\tilde {u}_{2}\right >\), shown in Fig. 6b attains only a peak value of ≈ 1/3 of the peak value of \(\left < \overline {u_{2}^{\prime } u_{2}^{\prime }}\right >\). The strongest spanwise dispersive stresses can be observed slightly above the roughness mid-plane. At this location, the DA streamwise velocity has attained a positive value. Above the roughness-midplane, the remaining roughness for an irregular isotropic Gaussian rough surface takes the form of peaks (see e.g. [28]). This means that the flow within the rough surface can start to meander around the peaks requiring spanwise motion to avoid the obstacles formed by the roughness peaks. This in turn leads to both positive and negative finite local time-averaged spanwise velocities giving rise to the observed spanwise normal dispersive stresses. As the height distribution of all current surfaces follows a Gaussian distribution, the peaks taper, which is why the levels of the spanwise normal dispersive stress reduce towards the maximum roughness height. For surfaces with streamwise elongated structures (SAR > 1) the levels of \(\left <\tilde {u}_{2}\tilde {u}_{2}\right >\) are lower, which can be explained by the different shape of the peaks and the long, streamwise-aligned voids for these rough surfaces that reduce the need for local spanwise diversions of the mean flow. For the surfaces with spanwise elongated structures (SAR < 1) the levels of spanwise dispersive stresses increase up to the case S14; S18 shows similar levels as S14. This increase can be attributed to the wider obstacles formed by the peaks for these surfaces. For the S118 case, a decrease in \(\left <\tilde {u}_{2}\tilde {u}_{2}\right >\) compared to S14 and S18 can be observed. A possible explanation for this behaviour may be that this surface approaches a transverse d-type bar roughness like state, i.e. the peaks tend to be so wide that horizontal circumnavigation becomes less important as the flow starts to skim past the cavities between the shortly-spaced irregular transverse bars. Related observations have been made in studies of turbulent flow over prismatic obstacles where the flow approaches a nominally two-dimensional behaviour over the obstacle when the width to height ratio exceeds 6 [44]. For the S118 surface a ratio of spanwise correlation length to height \({\mathcal{L}}_{y}/Sz_{5\times 5}\approx 9\) is reached. In the outer part of the flow, only minimal spanwise dispersive stresses can be observed.

The wall-normal Reynolds stress \(\left < \overline {u_{3}^{\prime } u_{3}^{\prime }}\right >\), see Fig. 7, shows the weakest roughness influence. For the cases with spanwise surface anisotropy, the levels of \(\left < \overline {u_{3}^{\prime } u_{3}^{\prime }}\right >\) are very close to the smooth-wall levels. The cases with SAR ≥ 1 show a small reduction of wall-normal velocity fluctuations; similar observations have been made for riblets [15]. Above the rough surfaces, the data of all rough cases shows a good collapse on the smooth-wall reference case for \(x_{3}/\delta \gtrsim 0.2\).

a Wall-normal Reynolds stresses; b wall-normal dispersive stresses. Line-types are given in Table 1. Smooth wall data \(\left (\circ \right )\) is also included for the Reynolds stress. The approximate location of the highest roughness crests is indicated by a vertical dotted line  at x3/δ = 0.11

at x3/δ = 0.11

The wall-normal dispersive stresses \(\left <\tilde {u}_{3}\tilde {u}_{3}\right >\), shown in Fig. 7b, are significantly weaker than the wall-normal Reynolds stresses with peak values of \(\lesssim 20\%\) of the corresponding Reynolds-stress peaks. The highest levels of \(\left <\tilde {u}_{3}\tilde {u}_{3}\right >\) are attained within the rough surfaces, while above the rough surface \(\left <\tilde {u}_{3}\tilde {u}_{3}\right >\) soon decays to close to zero values. Multiple peaks can be observed for \(\left <\tilde {u}_{3}\tilde {u}_{3}\right >\) for the spanwise anisotropic surfaces. This may be caused by recirculating flows induced between the ribs of these surfaces, which would be consistent with the higher negative values of the DA mean streamwise velocity observed for cases with SAR < 1 within the lower part of the rough surface.

The Reynolds shear stress \(-\left < \overline {u_{1}^{\prime } u_{3}^{\prime }}\right >\), shown in Fig. 8a, shows a good collapse on the smooth-wall case for x3/δ > 0.2. The peak value occurs for all rough surfaces close to the maximum height of the roughness, with the peak typically occuring below \(h_{\max \limits }\) for cases with SAR < 1, and just above \(h_{\max \limits }\) for cases with SAR > 1. This is due to a higher reduction of \(-\left < \overline {u_{1}^{\prime } u_{3}^{\prime }}\right >\) for the streamwise anisotropic cases. In the lower part of the roughness, very low values of negative \(-\left < \overline {u_{1}^{\prime } u_{3}^{\prime }}\right >\) occur for the spanwise anisotropic cases. A similar observation has been made by De Marchis et al. [35] for irregular sinusoidal roughness.

a Reynolds shear stress; b dispersive shear stress. Line-types are given in Table 1. Smooth wall data \(\left (\circ \right )\) is also included for the Reynolds stress. The approximate location of the highest roughness crests is indicated by a vertical dotted line  at x3/δ = 0.11

at x3/δ = 0.11

The levels of the dispersive shear stress \(-\left <\tilde {u}_{1}\tilde {u}_{3}\right >\) are significantly lower with peak levels of less than 1/4 of the Reynolds shear stress values. Above the rough surface, dispersive shear stress levels are very low, as should be expected based on the observed outer-layer similarity of the Reynolds shear stress. Within the surface, negative values of \(-\left <\tilde {u}_{1}\tilde {u}_{3}\right >\) occur for the spanwise anisotropic surfaces (SAR < 1). This would be consistent with recirculating, vortical structures in the mean flow between the transverse ribs of these surfaces.

4.4 Local dispersive and Reynolds stresses within the roughness canopy

The profiles of the dispersive stresses showed that the highest levels of dispersive stresses occured within the rough surface with the streamwise and spanwise normal dispersive stresses attaining the highest values overall. To illustrate the local distribution of the dispersive fluctuations, the streamwise and spanwise variations in the time-averaged flow field, \(\tilde {u}_{1}\) and \(\tilde {u}_{2}\), have been visualised in Fig. 9 in a horizontal plane at \(x_{3}\approx \frac {1}{2} h_{\max \limits }\) for a strongly spanwise anisotropic case, S18, the isotropic case, S11, and a strongly streamwise anisotropic case, S81. The highest negative values of \(\tilde {u}_{1}\) can be observed around the roughness peaks that breach the horizontal plane, where the local velocity always attains zero values, and in the wakes that form behind the peaks. The highest positive values of \(\tilde {u}_{1}\) are attained in areas away from the peaks, where the influence of the flow obstructions is minimized. The width of the wake is related to the streamwise correlation length of the surface \({\mathcal{L}}_{y}\), with surface S18 with the higher spanwise correlation length causing significantly wider wakes than S11 and S81, which have an equal, lower spanwise correlation length \({\mathcal{L}}_{y}\). High streamwise correlation length \({\mathcal{L}}_{x}\) promotes long coherent structures in the \(\tilde {u}_{1}\) field, as can be observed for case S81, with “channels” of high speed flow forming between the streamwise aligned rib-like structures of this surface. This explains the high levels of streamwise normal dispersive stress observed for cases with SAR > 1.

The spanwise variations in the time-averaged flow field, shown in Fig. 9d–f, exhibit the highest positive and negative values just upstream of the peaks where the mean flow is diverted to the positive and negative spanwise direction to circumnavigate a peak. This behaviour is strongly influenced by the typical peak shape and orientation. For the strongly spanwise anisotropic case S18, high levels of \(\tilde {u}_{2}\) can be observed upstream of the peaks that also show longer coherence in the spanwise direction compared to the isotropic and streamwise anisotropic cases. For the isotropic case S11, the typical negative - positive pattern is still predominant upstream of the peaks, however this occurs over significantly shorter distances in the spanwise direction, as the peaks are narrower. For the strongly streamwise anisotropic case S81, the negative-positive peak circumnavigation pattern is far less prevalent than for S11 and S18, and a lot of the observed moderate \(\tilde {u}_{2}\) values seem to be induced by the underlying surface pattern that promotes the streamwise channeling of \(\tilde {u}_{1}\) discussed above.

The local time-averaged streamwise and spanwise normal Reynolds stresses are visualised for the same plane in Fig. 10. The local streamwise Reynolds stress (see Fig. 10a–c) take their lowest values around the roughness peaks and in the wakes formed behind the peaks; overall low \(\overline {u_{1}^{\prime }u_{1}^{\prime }}\) is spatially correlated with negative \(\tilde {u}_{1}\). The highest values of \(\overline {u_{1}^{\prime }u_{1}^{\prime }}\) are attained in areas where \(\tilde {u}_{1}\) takes high positive values or has strong spanwise gradients. This is consistent with the observation that the surfaces with the highest streamwise dispersive shear stress, i.e. cases with SAR > 1, maintain the highest levels of streamwise Reynolds stresses.

The local time-averaged spanwise normal Reynolds stress (see Fig. 10d–f) also shows the lowest values in the wakes behind roughness elements. The highest values of \(\overline {u_{2}^{\prime }u_{2}^{\prime }}\) typically occur just upstream of the peaks, where the mean flow is diverted around the peaks (see discussion for \(\tilde {u}_{2}\) above). As wider peaks promote higher spanwise local Reynolds stresses over a wider region, the higher observed levels of spanwise normal Reynolds stresses in Fig. 6 for cases with SAR < 1 can also be related to the typical peak shape.

4.5 Effect of surface anisotropy on the anisotropy of the Reynolds stress tensor

The net anisotropy of the Reynolds stresses is commonly quantified based on the second IIb and third invariants IIIb of the normalised anisotropy tensor [32]

Based on IIb and IIIb the state of anisotropy can be characterised with the two variables η and ξ defined as

and

All realisable states of the Reynolds stress tensor are then contained within a triangle in the ξ − η-plane, the so-called Lumley triangle. Lumley triangle plots for all rough surfaces are shown in Fig. 11. In the reference smooth-wall turbulent channel flow, very close to the wall the flow is close to a 2-component state following the upper boundary of the Lumley triangle towards the 1-component state denoted by the upper right corner of the Lumley triangle. Maximum anisotropy is reached at \(x_{3}^{+}\approx 8\). For \(x_{3}^{+} >8\) the anisotropy decreases and the (ξ,η) curve follows a path close to the right boundary of the Lumley triangle, indicating a close to axisymmetric, rod-like state and approaching, but not reaching, the state of maximum isotropy at the bottom point of the Lumley triangle as \(x_{3}^{+}\) increases.

Lumley triangles for all rough surfaces in order of ascending SAR. The smooth wall data case is shown for reference  . The location of the roughness mean plane is highlighted using a green triangle, and \(h_{\max \limits }\) using a yellow triangle. Blue lines correspond to cases with SAR < 1 and red lines to cases with SAR > 1 (see Table 1)

. The location of the roughness mean plane is highlighted using a green triangle, and \(h_{\max \limits }\) using a yellow triangle. Blue lines correspond to cases with SAR < 1 and red lines to cases with SAR > 1 (see Table 1)

In all cases with surface anisotropy, i.e. all cases except S11, in the deepest pits of the surface the Reynolds stress anisotropy tensor is close to a strongly anisotropic, 1-component case. With increasing height within the rough surface, strongly streamwise anisotropic cases follow a different path on the (ξ,η)-map compared the cases with spanwise anisotropy: For the spanwise anisotropic and the isotropic surfaces, the flow approaches the left side of the Lumley triangle, reaching an axisymmetric disk-like (oblate spheroid) state at the roughness mean plane; at this location, the streamwise and spanwise Reynolds stresses are of comparable magnitude. An axisymmetric, disk-like state of the Reynolds stress anisotropy tensor is typical of mixing layers [32]. Similar behaviour has also been observed for turbulent flow over transverse bar roughness [45] and k-type roughness [46]. Above the roughness mean-plane, the path returns to the right side of the triangle, i.e. close to an axisymmetric, rod-like (prolate spheroid) state and tracks the behaviour of the smooth-wall case once the wall-normal coordinate exceeds the maximum roughness height (approximate location indicated by yellow triangles in Fig. 11).

In contrast, for the cases with strong streamwise anisotropy, i.e. S161 and S81, the turbulent state remains close to the right side of the Lumley triangle for all x3 values. Cases with mild streamwise anisotropy show a mixed behaviour. The S21 state still reaches the left side of the Lumley triangle and the S41 case approaches it. However this occurs at values of x3 below the roughness mean plane. At the roughness mean plane, the turbulence for the two latter cases has already returned to a state closer to the right side of the triangle, i.e. a state that is closer to the smooth-wall channel flow behaviour.

Overall, the highest dependency of the Reynolds stress anisotropy on surface anisotropy can be observed below the highest roughness crest where the strongly streamwise anisotropic surfaces induce a behaviour that is distinct from the isotropic and spanwise anisotropic surfaces. Above the highest roughness crest, a good collapse on the smooth-wall behaviour can be observed in all cases. This can also be observed by considering the determinant of the normalised Reynolds stress tensor F, which is related to η and ξ by

F is zero in the case of pure 2-component turbulence and F = 1 for perfectly isotropic, three-dimensional turbulence. As shown in Fig. 12, above the highest roughness crest all rough-wall cases collapse on the smooth-wall data, giving another statistic where outer-layer similarity is observed.

Determinant of Reynolds anisotropy tensor F. Line-types are given in Table 1. Smooth wall data \(\left (\circ \right )\) is also included

5 Conclusions

DNS of rough-wall turbulent channel flow over synthetically generated irregular surfaces with specified correlation lengths were performed at a friction Reynolds number of 395. The ratio of the streamwise and spanwise correlation lengths was used to define the surface anisotropy ratio (SAR) parameter. Nine surfaces were considered: an isotropic surface \(\left (\text {SAR}=1\right )\), four streamwise-anisotropic surfaces \(\left (\text {SAR}>1\right )\) and four spanwise-anisotropic surfaces \(\left (\text {SAR}<1\right )\). The surface height distribution of the surfaces followed an approximately Gaussian distribution in all cases with surface skewness Ssk ≈ 0 and kurtosis Sku ≈ 3. This enables this investigation to focus on the influence of surface roughness anisotropy on the near-wall turbulent flow.

For the surfaces considered in this study, the roughness function, ΔU+, exhibits an over 200% increase as the SAR parameter is decreased from ≈ 16 to 1/4 (Fig. 3). For very low SAR (SAR ≤ 1/4) the roughness functions attains an approximately constant value. Considering that each surface has a near-Gaussian height distribution and the same mean peak-to-valley height (Table 1), the sensitivity of ΔU+ with respect to the SAR parameter underlines the strong effect that surface anisotropy has upon determining the momentum deficit in the outer flow. We find that ΔU+ decreases approximately exponentially with increasing SAR (see Fig. 3a) for SAR ≥ 1/8.

In the present work, Raupach & Shaw’s [33] double-averaging methodology was employed in order to delineate the statistical contributions of “form-induced” dispersive variations in the time-averaged flow field from the turbulent fluctuations around the local mean. For all Reynolds stress profiles, outer-layer similarity was recovered. Relative to the smooth-wall case, there is a strong reduction of the near-wall peak of the streamwise normal Reynolds stress profile, with the lowest reduction observed for the streamwise anisotropic cases and the highest reductions for the spanwise anisotropic surfaces. The level of the spanwise normal Reynolds stresses were comparable to the smooth-wall case, with slightly elevated levels observed for the spanwise anisotropic cases. The wall-normal Reynolds stress profiles was only very weakly modified in the rough cases compared to the smooth-wall case.

The dispersive stresses for all cases attained only very low values above the rough surface indicating the absence of strong large-scale secondary flows. This is expected, as for flow over regular streamwise aligned bars a spacing of S/δ ≥ 0.5 is required to allow the growth of strong secondary vortex-structures above the rough surface [13]. For the current surfaces, the short spanwise correlation length, \({\mathcal{L}}_{y}\approx 0.1/\delta \), for the streamwise anisotropic surfaces prevents the emergence of streamwise-aligned vortical structures. In turn, for the spanwise anisotropic surfaces, the streamwise correlation length, \({\mathcal{L}}_{x}\approx 0.1/\delta \), is too short to promote large-scale spanwise aligned vortical structures. Within the rough surfaces, mainly the streamwise and spanwise dispersive stresses attain significant values. The streamwise normal dispersive stress exceeds the levels of the corresponding Reynolds stress for the strongly streamwise anisotropic cases. This can be attributed to the emergence of “channeling” within the rough surface. The spanwise dispersive stresses observed within the rough surface mainly arise from the mean flow circumnavigating the peaks in the upper half of the rough surface. The much weaker wall-normal dispersive stresses also show that the mean flow within the rough surface mainly relies on spanwise motion to avoid the roughness peaks instead of following a normal motion to cross above the peaks. In conclusion, the degree of surface anisotropy and its orientation with respect to the mean flow need to be taken into account when considering turbulent flow over irregular anisotropic rough surfaces, as the roughness effect on the mean flow is strongly influenced by SAR even for moderate SAR values.

Highly streamwise anisotropic irregular rough surfaces pose interesting questions for further research. Considering the much lower ΔU+ values observed for the highly streamwise anisotropic cases in the current study, the question arises whether a riblet-type effect, i.e. ΔU+ < 0, is possible in the context of irregular rough surfaces. To this end, surfaces with much shorter spanwise correlation length, mimicking the typical spacing of regular riblets, should be investigated. In contrast, an irregular rough surface with higher spanwise correlation length while maintaining high streamwise anisotropy could be used to investigate strong large-scale secondary flows above the roughness, similar to those observed by Barros & Christensen for a damaged turbine blade [24] and by Vidal et al. [11] for regular spanwise sinusoidal roughness.

References

Thomas, T.R., Rosén, B.G., Amini, N.: Fractal characterisation of the anisotropy of rough surfaces. Wear 232, 41–50 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0043-1648(99)00128-3

Bons, J.P., Taylor, R.P., McClain, S.T., Rivir, R.B.: The many faces of turbine surface roughness. J. Turbomach. 123, 739–748 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1115/1.1400115

Monty, J.P., Dogan, E., Hanson, R., Scardino, A.J., Ganapathisubramani, B., Hutchins, N.: An assessment of the ship drag penalty arising from light calcareous tubeworm fouling. Biofouling 32, 451–464 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1080/08927014.2016.1148140

Jackson, D.W.T., Bourke, M.C., Smyth, T.A.G.: The dune effect on sand-transporting winds on Mars. Nat. Commun. 6, 8796 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms9796

Hwang, P.A., Burrage, D.M., Wang, D.W., Wesson, J.C.: Ocean surface roughness spectrum in high wind condition for microwave backscatter and emission computations. J. Atmos. Ocean Tech. 30, 2168–2188 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1175/JTECH-D-12-00239.1

Jenkins, A.D., Paskyabi, M.B., Fer, I., Gupta, A., Adakudly, M.: Modelling the effect of ocean waves on the atmospheric and ocean boundary layers. Energy Procedia 24, 166–175 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2012.06.098

Thakkar, M., Busse, A., Sandham, N.D.: Surface correlation of hydrodynamic drag for transitionally rough engineering surfaces. J. Turbul. 138, 138–169 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1080/14685248.2016.1258119

Perry, A.E., Schofield, W.H., Joubert, P.N.: Rough wall turbulent boundary layers. J. Fluid Mech. 37, 383–413 (1969). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112069000619

Leonardi, S., Orlandi, P., Djenidi, L., Antonia, R.A.: Structure of turbulent channel flow with square bars on one wall. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 25, 384–392 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatfluidflow.2004.02.022

Hamed, A.M., Kamdar, A., Xastillo, L., Chamorrro, L.: Turbulent boundary layer over 2D and 3D large-scale wavy walls. Phys. Fluids 27, 106601 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4933098

Vidal, A., Nagib, H.M., Schlatter, P., Vinuesa, R.: Secondary flow in spanwise-periodic in-phase sinusoidal channels. J. Fluid Mech. 851, 288–316 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2018.498

Orlandi, P., Leonardi, S.: DNS of turbulent channel flows with two- and three-dimensional roughness. J. Turbul. 7, 53 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1080/14685240600827526

Vanderwel, C., Ganapathisubramani, B.: Effects of spanwise spacing on large-scale secondary flows in rough-wall turbulent boundary layers. J. Fluid Mech. 774, R2 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2015.292

Bechert, D.W., Bartenwerfer, M.: The viscous flow on surfaces with longitudinal ribs. J. Fluid Mech. 206, 105–129 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112089002247

Choi, H., Moin, P., Kim, J.: Direct numerical simulation of turbulent flow over riblets. J. Fluid Mech. 255, 503–539 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112093002575

García-Mayoral, R., Jiménez, J.: Drag reduction by riblets. Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. A 369, 1412 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2010.0359

García-Mayoral, R., Jiménez, J.: Hydrodynamic stability and breakdown of the viscous regime over riblets. J. Fluid Mech. 678, 317–347 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2011.114

Liu, K.N., Christodoulou, C., Riccius, O., Joseph, D.D.: Drag reduction in pipes lined with riblets. AIAA J. 28(10), 1697 (1990). https://doi.org/10.2514/3.10459

Yuan, J., Piomelli, P.: Estimation and prediction of the roughness function on realistic surfaces. J. Turbul. 15, 350–365 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1080/14685248.2014.907904

Busse, A., Thakkar, M., Sandham, N.D.: Reynolds-number dependence of the near-wall flow over irregular rough surfaces. J. Fluid Mech. 810, 196–224 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2016.680

Forooghi, P., Stroh, A., Schlatter, P., Frohnapfel, B.: Direct numerical simulation of flow over dissimilar, randomly distributed roughness elements: a systematic study on the effect of surface morphology on turbulence. Phys. Rev. Fluids 3, 044605 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevFluids.3.044605

Barros, J.M., Schultz, M.P., Flack, K.A.: Measurements of skin-friction of systematically generated surface roughness. Int. J. Heat Fluid Fl. 72, 1–7 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatfluidflow.2018.04.015

Wu, Y., Christensen, K.T.: Spatial structure of a turbulent boundary layer with irregular surface roughness. J. Fluid Mech. 655, 380–418 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112010000960

Barros, J.M., Christensen, K.T.: Observations of turbulent secondary flows in a rough-wall boundary layer. J. Fluid Mech. 748, R1 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2014.218

Patir, N.: A numerical procedure for random generation of rough surfaces. Wear 47, 263–277 (1978). https://doi.org/10.1016/0043-1648(78)90157-6

Busse, A., Lützner, M., Sandham, N.D.: Direct numerical simulation of turbulent flow over a rough surface based on a surface scan. Comp. Fluids 116, 1290147 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compfluid.2015.04.008

Blateyron, F.: Characterisation of areal surface texture, chap. The areal field parameters, pp. 15–43. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-36458-7_2 (2013)

Jelly, T.O., Busse, A.: Reynolds and dispersive stress contributions above highly skewed roughness. J. Fluid Mech. 852, 710–724 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2018.541

Napoli, E., Armenio, V., De Marchis, M.: The effect of the slope of irregularly distributed roughness elements on turbulent wall-bounded flows. J. Fluid Mech. 613, 385–394 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112008003571

Mainsah, E., Greenwood, J.A., Chetwynd D.G. (eds.): Metrology and properties of engineering surfaces. Kluwer Academic Publishers (2001)

Yang, J., Balaras, E.: An embedded-boundary formulation for large-eddy simulation of turbulent flows interacting with moving boundaries. J. Comp. Phys. 215, 12 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcp.2005.10.035

Pope, S.B.: Turbulent flows. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2000)

Raupach, M.R., Shaw, R.H.: Averaging procedures for flow within vegetation canopies. Boundary-Layer Meteorol. 22, 79–90 (1982). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00128057

Chan, L., MacDonald, M., Chung, D., Hutchins, N., Ooi, A.: A systematic investigation of roughness height and wavelength in turbulent pipe flow in the transitionally rough regime. J. Fluid Mech. 771, 743–777 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2015.172

De Marchis, M., Napoli, E., Armenio, V.: Turbulence structures over irregular rough surfaces. J.Turbul. 11(3), 1–32 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1080/14685241003657270

Schultz, M.P., Flack, K.A.: Turbulent boundary layers on a systematically varied rough wall. Phys. Fluids 21, 015104 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3059630

Flack, K.A., Schultz, M.P.: Review of hydraulic roughness scales in the fully rough regime. J. Fluids Eng. 132, 041203 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4001492

Townsend, A.A.: The structure of turbulent shear flow. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1976)

Flack, K.A., Schultz, M.P.: Roughness effects on wall-bounded turbulent flows. Phys. Fluids 26, 101305 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4896280

Flack, K.A., Schultz, M.P., Shapiro, T.A.: Experimental support for Townsend’s Reynolds number similarity hypothesis on rough walls. Phys. Fluids 17, 035102 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1843135

Schultz, M., Flack, K.: The rough-wall turbulent boundary layer from the hydraulically smooth to the fully rough regime. J. Fluid Mech. 580, 381–405 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112007005502

Monnier, B., Goudarzi, S.A., Vinuesa, R., Wark, C.: Turbulent structure of a simplified urban fluid flow studied through stereoscopic particle image velocimetry. Boundary-Layer Meteorol. 166, 239–268 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10546-017-0303-9

Oke, T.R.: Street design and urban canopy layer climate. Energ. Buildings 11, 103–113 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-7788(88)90026-6

Martinuzzi, R., Tropea, C.: The flow around surface-mounted, prismatic obstacles placed in a fully developed channel flow. J. Fluids Eng. 115, 85–92 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1115/1.2910118

Ashrafian, A., Andersson, H.I.: The structure of turbulence in a rod-roughened channel. Int. J. Heat Fluid Fl. 27, 65–79 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatfluidflow.2005.04.006

Smalley, R.J., Leonardi, S., Antonia, R.A., Djenidi, L., Orlandi, P.: Reynolds stress anisotropy of turbulent rough wall layers. Exp. Fluids 33, 31–37 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00348-002-0466-z

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge support by the United Kingdom Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) via grant numbers EP/P004687/1 and EP/P009875/1. The authors would also like to thank for compute time on the ARCHER supercomputing facility (https://doi.org/http://www.archer.ac.uk) via the UK Turbulence Consortium (grant EP/L000261/1). Roughness height maps and velocity statistics are available in .csv format at https://doi.org/10.5525/gla.researchdata.877.

Funding

This study was funded by the United Kingdom Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) (grant numbers EP/P004687/1, EP/P009875/1 and EP/L000261/1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

There is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The authors gratefully acknowledge support by the United Kingdom Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) via grant numbers EP/P004687/1, EP/P009875/1 and EP/L000261/1.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Busse, A., Jelly, T.O. Influence of Surface Anisotropy on Turbulent Flow Over Irregular Roughness. Flow Turbulence Combust 104, 331–354 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10494-019-00074-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10494-019-00074-4