Abstract

Purposes

(1) Determine the association of multiple cancers with smoking, focusing on cancers with an uncertain association; and (2) illustrate quantitative bias analysis as applied to registry data, to adjust for misclassification of smoking and residual confounding by alcohol and obesity.

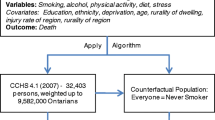

Methods

New Zealand 1981 and 1996 censuses, including smoking questions, were linked to cancer registry data giving 14.8 million person-years of follow-up. Rate ratios (RR) for current versus never smokers, adjusting for age, sex, ethnicity and socioeconomic factors were calculated and then subjected to quantitative bias analysis.

Results

RR estimates for lung, larynx (including ear and nasosinus), and bladder cancers adjusted for measured confounders and exposure misclassification were 9.28 (95 % uncertainty interval 8.31–10.4), 6.14 (4.55–8.30), and 2.22 (1.94–2.55), respectively. Moderate associations were found for cervical (1.82; 1.51–2.20), kidney (1.29; 1.07–1.56), liver cancer (1.75; 1.37–2.24; European only), esophageal (2.14; 1.73–2.65), oropharyngeal (2.30; 1.94–2.72), pancreatic (1.68; 1.44–1.96), and stomach cancers (1.42; 1.22–1.66). Protective associations were found for endometrial (0.67; 0.56–0.79) and melanoma (0.72; 0.65–0.81), and borderline association for thyroid (0.76; 0.58–1.00), colon (0.89; 0.81–0.98), and CML (0.66; 0.44–0.99). Remaining cancers had near null associations. Adjustment for residual confounding suggested little impact, except the RRs for endometrial, kidney, and esophageal cancers were slightly increased, and the oropharyngeal and liver (European/other) RRs were decreased.

Conclusions

Our large study confirms the strong association of smoking with many cancers and strengthens the evidence for protective associations with thyroid cancer and melanoma. With large data sets, considering and adjusting for residual systematic error is as important as quantifying random error.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

International Agency for Research on Cancer (2004) Tobacco smoke and involuntary smoking. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum 83:1–1187

Office of the Surgeon General (2004) The health consequences of smoking: a report of the Surgeon General. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, Washington, DC

Blakely T et al (2010) CancerTrends: trends in cancer incidence by ethnic and socioeconomic group, New Zealand 1981–2004. University of Otago, and Ministry of Health, Wellington. www.wnmeds.ac.nz/academic/dph/research/HIRP/CancerTrends/CancerPublications.html

Blakely T, Wilson N (2005) The contribution of smoking to inequalities in mortality by education varies over time and by sex: two national cohort studies, 1981–84 and 1996–99. Int J Epidemiol 34(5):1054–1062

Hunt D et al (2005) The smoking-mortality association varies over time and by ethnicity in New Zealand. Int J Epidemiol 34:1020–1028

Blakely T et al (2006) What is the contribution of smoking and socioeconomic position to ethnic inequalities in mortality in New Zealand? Lancet 368(9529):44–52

Salmond C et al (2012) A decade of tobacco control efforts in New Zealand (1996–2006): impacts on inequalities in census-derived smoking prevalence. Nicotine Tob Res 14(6):664–673

Edwards R et al (2012) Setting a good example? Changes in smoking prevalence among key occupational groups in New Zealand: evidence from the 1981 and 2006 censuses. Nicotine Tob Res 14(3):329–337

Cornfield J et al (1959) Smoking and lung cancer: recent evidence and a discussion of some questions. J Natl Cancer Inst 22:173–203

Lash T, Fox M, Fink A (2009) Applying quantitative bias analysis to epidemiological data. Springer, New York

Greenland S, Lash T (2008) Bias analysis. In: Rothman K, Greenland S, Lash T (eds) Modern epidemiology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp 345–380

Greenland S (2009) Bayesian perspectives for epidemiologic research: III. Bias analysis via missing-data methods. Int J Epidemiol 38:1662–1673

Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer (2002) Alcohol, tobacco and breast cancer—collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 53 epidemiological studies, including 58,515 women with breast cancer and 95,067 women without the disease. Br J Cancer 87(11):1234–1245

Terry PD, Rohan TE (2002) Cigarette smoking and the risk of breast cancer in women: a review of the literature. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 11(10 Pt 1):953–971

Reynolds P et al (2004) Active smoking, household passive smoking, and breast cancer: evidence from the California Teachers Study. J Natl Cancer Inst 96(1):29–37

Cui Y, Miller AB, Rohan TE (2006) Cigarette smoking and breast cancer risk: update of a prospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 100(3):293–299

IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans (2012) A review of human carcinogens: part E—personal habits and indoor combustions. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon

Botteri E et al (2008) Smoking and colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. JAMA 300(23):2765–2778

Liang PS, Chen TY, Giovannucci E (2009) Cigarette smoking and colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 124(10):2406–2415

Peach HG, Barnett NE (2001) Critical review of epidemiological studies of the association between smoking and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Hematol Oncol 19(2):67–80

Morton LM et al (2005) Cigarette smoking and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a pooled analysis from the International Lymphoma Epidemiology Consortium (interlymph). Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 14(4):925–933

Adami J et al (1998) Smoking and the risk of leukemia, lymphoma, and multiple myeloma (Sweden). Cancer Causes Control 9(1):49–56

Brownson RC, Novotny TE, Perry MC (1993) Cigarette smoking and adult leukemia. A meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 153(4):469–475

Siegel M (1993) Smoking and leukemia: evaluation of a causal hypothesis. Am J Epidemiol 138(1):1–9

Gandini S et al (2008) Tobacco smoking and cancer: a meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 122(1):155–164

Kurian AW et al (2005) Histologic types of epithelial ovarian cancer: have they different risk factors? Gynecol Oncol 96(2):520–530

Jordan SJ et al (2006) Does smoking increase risk of ovarian cancer? A systematic review. Gynecol Oncol 103(3):1122–1129

Collaborative Group on Epidemiological Studies of Ovarian Cancer (2012) Ovarian cancer and smoking: individual participant meta-analysis including 28 114 women with ovarian cancer from 51 epidemiological studies. Lancet Oncol 13(9):946–956

Blakely T et al (1999) Hepatitis B carriage explains the excess rate of hepatocellular carcinoma for Maori, Pacific Island, and Asian people compared to Europeans in New Zealand. Int J Epidemiol 28:204–210

Lee YC et al (2009) Meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies on cigarette smoking and liver cancer. Int J Epidemiol 38(6):1497–1511

Freedman DM et al (2003) Risk of melanoma in relation to smoking, alcohol intake, and other factors in a large occupational cohort. Cancer Causes Control 14(9):847–857

Odenbro A et al (2007) The risk for cutaneous malignant melanoma, melanoma in situ and intraocular malignant melanoma in relation to tobacco use and body mass index. Br J Dermatol 156(1):99–105

Mack WJ et al (2003) A pooled analysis of case-control studies of thyroid cancer: cigarette smoking and consumption of alcohol, coffee, and tea. Cancer Causes Control 14(8):773–785

Atkinson J et al (2010) CancerTrends technical report 1. Linkage of Census and Cancer Registrations, 1981–2004. University of Otago, Wellington

Salmond C, Crampton P (2001) NZDep96: what does it measure? Soc Policy J N Z 17:82–100

Heller W et al (1998) Misclassification of smoking in a follow-up population study in southern Germany. J Clin Epidemiol 51(3):211–218

Ministry of Health (2004) A portrait of health: key results of the 2002/03 New Zealand Health Survey. Ministry of Health, Wellington

Renehan AG et al (2008) Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet 371(9612):569–578

Key J et al (2006) Meta-analysis of studies of alcohol and breast cancer with consideration of the methodological issues. Cancer Causes Control 17(6):759–770

Fedirko V et al (2011) Alcohol drinking and colorectal cancer risk: an overall and dose–response meta-analysis of published studies. Ann Oncol 22(9):1958–1972

Bagnardi V et al (2001) Alcohol consumption and the risk of cancer: a meta-analysis. Alcohol Res Health 25(4):263–270

Tramacere I, La Vecchia C, Negri E (2011) Tobacco smoking and esophageal and gastric cardia adenocarcinoma: a meta-analysis. Epidemiology 22(3):344–349

Zhou B et al (2008) Cigarette smoking and the risk of endometrial cancer: a meta-analysis. Am J Med 121(6):501.e3–508.e3

Baron JA, La Vecchia C, Levi F (1990) The antiestrogenic effect of cigarette smoking in women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 162(2):502–514

Westerdahl J et al (1996) Risk of malignant melanoma in relation to drug intake, alcohol, smoking and hormonal factors. Br J Cancer 73(9):1126–1131

Sopori M (2002) Effects of cigarette smoke on the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 2(5):372–377

Gandini S et al (2008) Tobacco smoking and cancer: a meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 122(1):155–164

Appleby P et al (2006) Carcinoma of the cervix and tobacco smoking: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 13,541 women with carcinoma of the cervix and 23,017 women without carcinoma of the cervix from 23 epidemiological studies. Int J Cancer 118(6):1481–1495

Vineis P et al (2004) Tobacco and cancer: recent epidemiological evidence. J Natl Cancer Inst 96(2):99–106

Hunt JD et al (2005) Renal cell carcinoma in relation to cigarette smoking: meta-analysis of 24 studies. Int J Cancer 114(1):101–108

Huncharek M et al (2010) Smoking as a risk factor for prostate cancer: a meta-analysis of 24 prospective cohort studies. Am J Public Health 100(4):693–701

Acknowledgments

Access to the data used in this study was provided by Statistics New Zealand under conditions designed to give effect to the security and confidentiality provisions of the Statistics Act 1975. The results presented in this study are the work of the authors, not Statistics New Zealand.

Ethical standards

The Wellington Ethics Committee granted ethics approval for CancerTrends (Ref 04/10/093).

Funding

The authors received funds from Health Research Council of New Zealand.

Conflict of interest

JJB is founder and owner of Epigear, which sells the Ersatz software used in the analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Blakely, T., Barendregt, J.J., Foster, R.H. et al. The association of active smoking with multiple cancers: national census-cancer registry cohorts with quantitative bias analysis. Cancer Causes Control 24, 1243–1255 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-013-0204-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-013-0204-2