Abstract

Purpose

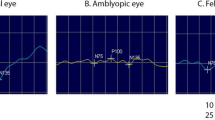

An orientation-specific visual evoked potential (osVEP) protocol was developed to probe meridional anisotropies in children with refractive amblyopia. The aim was to characterise the osVEP response in children with bilateral refractive amblyopia, evaluate the intra-session repeatability of the main osVEP components (C1, C2 and C3), coefficient of repeatability (CoR) of the response to gratings in different meridians and determine if refractive amblyopes have poorer repeatability as compared with non-amblyopic controls.

Methods

Children aged 4–7 years with newly diagnosed and untreated bilateral refractive amblyopia and non-amblyopic controls were recruited. Orientation-specific pattern-onset VEPs were recorded in response to an achromatic sinewave grating stimulus of 4 cycles per degree under monocular and binocular stimulation. The grating lines used for monocular stimulation were parallel with the subjects’ most positive and negative astigmatic meridians when considered in sphero-minus cylinder form (Meridians 1 and 2, respectively). In subjects without astigmatism, meridians 1 and 2 were designated horizontal and vertical gratings, respectively. Binocular stimuli were presented with grating lines parallel to meridians 45, 90, 135 and 180°. The repeatability of latencies of the main osVEP components (C1, C2 and C3) were investigated using two successive osVEPs recordings for each stimulus meridian and the CoR for each component’s latencies were assessed.

Results

Seven amblyopic children (Visual acuity (VA) ranging from 0.08 to 0.40 LogMAR in the less amblyopic eye and 0.26–0.52 LogMAR in the more amblyopic eye) and 7 non-amblyopic controls (VA ranging from 0.00 to 0.02 LogMAR in either eye), with a median age of 4.6 and 7.0 years, respectively, completed the study. C1 had the highest CoR for most conditions assessed. Ratio of CoRs C1:C2 was > 2 for all binocular meridians in controls and the 90 and 180 meridians in the amblyopes; C1:C3 was > 2 for the binocularly assessed 45, 90 and 135 meridians in the controls and the 90 and 180 meridians in the amblyopes; C2:C3 were all < 2 for all meridians assessed in both groups.

Conclusions

The osVEP waveforms are reliable and useful for future investigations into the meridional anisotropies in children with refractive amblyopia, particularly the C3 component. Component C1 had the poorest repeatability, which consequentially affected C2 amplitude estimation. Only C3 amplitude and latency could be consistently estimated as C2 and C3 latencies were similarly repeatable. Coefficients of repeatability of osVEP latencies did not appear to systematically differ between non-amblyopic and amblyopic children.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Amos JF (1978) Refractive amblyopia: a differential diagnosis. J Am Optom Assoc 49(4):361–366

Shaw DE et al (1988) Amblyopia–factors influencing age of presentation. Lancet 2(8604):207–209

Beauchamp RI (1990) Normal development of the neural pathways. In: Rosenbloom AA, Morgan MW (eds) Principles and practice of pediatric optometry. Lippincott, USA, pp 46–65

Williams C et al (2008) Prevalence and risk factors for common vision problems in children: data from the ALSPAC study. Br J Ophthalmol 92(7):959–964

Li X et al (2007) Cortical deficits in human amblyopia: their regional distribution and their relationship to the contrast detection deficit. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 48(4):1575–1591

Donnelly UM, Stewart NM, Hollinger M (2005) Prevalence and outcomes of childhood visual disorders. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 12(4):243–250

Robaei D et al (2006) Causes and associations of amblyopia in a population-based sample of 6-year-old Australian children. Arch Ophthalmol 124(6):878–884

Beck RW (2002) Clinical research in pediatric ophthalmology: the Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 13(5):337–340

Yap TP, Boon MY (2020) Electrodiagnosis and treatment monitoring of children with refractive amblyopia. Adv Ophthalmol Optom 5:1–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yaoo.2020.04.001

Kelly JP et al (2015) Occlusion therapy improves phase-alignment of the cortical response in amblyopia. Vision Res 114:142–150

Arden GB, Barnard WM (1979) Effect of occlusion on the visual evoked response in amblyopia. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K 99(3):419–426

Friendly DS et al (1986) Pattern-reversal visual-evoked potentials in the diagnosis of amblyopia in children. Am J Ophthalmol 102(3):329–339

Furuskog P, Persson HE, Wanger P (1987) Subnormal visual acuity in children: prognosis and visual evoked cortical potential findings. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 65(6):668–672

Henc-Petrinovic L et al (1993) Prognostic value of visual evoked responses in childhood amblyopia. Eur J Ophthalmol 3(3):114–120

Odom JV, Hoyt CS, Marg E (1981) Effect of natural deprivation and unilateral eye patching on visual acuity of infants and children. Evoked potential measurements. Arch Ophthalmol 99(8):1412–1416

Wilcox LM Jr, Sokol S (1980) Changes in the binocular fixation patterns and the visually evoked potential in the treatment of esotropia with amblyopia. Ophthalmology 87(12):1273–1281

Weiss AH, Kelly JP (2004) Spatial-frequency-dependent changes in cortical activation before and after patching in amblyopic children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 45(10):3531–3537

Sokol S, Bloom B (1973) Visually evoked cortical responses of amblyopes to a spatially alternating stimulus. Invest Ophthalmol 12(12):936–939

Wildberger H (1982) The relationship between visual evoked potentials (VEPs) and visual acuity in amblyopia. Docum Ophthal Proc Ser 31:385–390

Oner A et al (2004) Pattern VEP is a useful technique in monitoring the effectiveness of occlusion therapy in amblyopic eyes under occlusion therapy. Doc Ophthalmol 109(3):223–227

Azmy R, Zedan RH (2016) Monitoring occlusion therapy in amblyopic children using pattern visual evoked potential. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatry Neurosurg 53(1):1–5

Robson AG et al (2018) ISCEV guide to visual electrodiagnostic procedures. Doc Ophthalmol 136(1):1–26

Chung W et al (2008) Pattern visual evoked potential as a predictor of occlusion therapy for amblyopia. Korean J Ophthalmol 22(4):251–254

Ohn YH et al (1994) Snellen visual acuity versus pattern reversal visual-evoked response acuity in clinical applications. Ophthalmic Res 26(4):240–252

Galloway NR, Barber C (1982) Transient visual evoked potential monitoring of disuse amnblyopia. Docum Ophthal Proc Series 31:377–384

Arden GB, Barnard WM, Mushin AS (1974) Visually evoked responses in amblyopia. Br J Ophthalmol 58(3):183–192

Sokol S (1983) Abnormal evoked potential latencies in amblyopia. Br J Ophthalmol 67(5):310–314

Baker DH, Meese TS, Hess RF (2008) Contrast masking in strabismic amblyopia: attenuation, noise, interocular suppression and binocular summation. Vis Res 48(15):1625–1640

Levi DM, Klein SA (1986) Sampling in spatial vision. Nature 320(6060):360–362

Roelfsema PR et al (1994) Reduced synchronization in the visual cortex of cats with strabismic amblyopia. Eur J Neurosci 6(11):1645–1655

Di Russo F et al (2002) Cortical sources of the early components of the visual evoked potential. Hum Brain Mapp 15(2):95–111

Foxe JJ, Simpson GV (2002) Flow of activation from V1 to frontal cortex in humans. A framework for defining “early” visual processing. Exp Brain Res 142(1):139–150

Schroeder CE, Mehta AD, Givre SJ (1998) A spatiotemporal profile of visual system activation revealed by current source density analysis in the awake macaque. Cereb Cortex 8(7):575–592

Kothari R et al (2016) A comprehensive review on methodologies employed for visual evoked potentials. Scientifica 2016:9852194

McCulloch DL, Skarf B (1991) Development of the human visual system: monocular and binocular pattern VEP latency. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 32(8):2372–2381

Kriss A, Russell-Eggitt I (1992) Electrophysiological assessment of visual pathway function in infants. Eye 6(Pt 2):145–153

Gwiazda J, Scheiman M, Held R (1984) Anisotropic resolution in children’s vision. Vis Res 24(6):527–531

Carkeet A et al (2003) Modulation transfer functions in children: pupil size dependence and meridional anisotropy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 44(7):3248–3256

Yap TP et al (2019) Electrophysiological and psychophysical studies of meridional anisotropies in children with and without astigmatism. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 60(6):1906–1913

Charman WN, Voisin L (1993) Optical aspects of tolerances to uncorrected ocular astigmatism. Optom Vis Sci 70(2):111–117

Harvey EM (2009) Development and treatment of astigmatism-related amblyopia. Optom Vis Sci 86(6):634–639

Freeman RD, Thibos LN (1975) Visual evoked responses in humans with abnormal visual experience. J Physiol 247:711–724

Boon MY et al (2016) Fractal dimension analysis of transient visual evoked potentials: optimisation and applications. PLoS ONE 11(9):e0161565

Yap TP, Luu CD, Suttle C, Chia A, Boon MY (2020) Effect of stimulus orientation on visual function in children with refractive amblyopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 61(5):5. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.61.5.5

Crognale MA et al (1998) Development of the spatio-chromatic visual evoked potential (VEP): a longitudinal study. Vis Res 38(21):3283–3292

Kriss A, Russell-Eggitt I, Taylor D (1990) Childhood albinism. Visual electrophysiological features. Ophthalmic Paediatr Genet 11(3):185–192

Brecelj J et al (2002) Pattern ERG and VEP maturation in schoolchildren. Clin Neurophysiol 113(11):1764–1770

Boon MY et al (2009) Dynamics of chromatic visual system processing differ in complexity between children and adults. J Vis 9(6):1–17

Thompson DA et al (2017) The changing shape of the ISCEV standard pattern onset VEP. Doc Ophthalmol 135(1):69–76

De Vries-Khoe L, Spekreijse H (1982) Maturation of luminance and pattern EPs in man. Doc Ophthalmol Proc 31:461–475

Davis AR et al (2006) Differential changes of magnocellular and parvocellular visual function in early- and late-onset strabismic amblyopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 47(11):4836–4841

Boon MY, Suttle CM, Henry B (2005) Estimating chromatic contrast thresholds from the transient visual evoked potential. Vis Res 45(18):2367–2383

Boon MY et al (2008) The correlation dimension: a useful objective measure of the transient visual evoked potential? J Vis 8(1):1–21

Banko EM et al (2014) Amblyopic deficit beyond the fovea: delayed and variable single-trial ERP response latencies, but unaltered amplitudes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 55(2):1109–1117

Banko EM et al (2013) Amblyopic deficits in the timing and strength of visual cortical responses to faces. Cortex 49(4):1013–1024

Barlow HB (1957) Increment thresholds at low intensities considered as signal/noise discriminations. J Physiol 136(3):469–488

Pelli DG, Farell B (1999) Why use noise? J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis 16(3):647–653

Pelli DG, Levi DM, Chung STL (2004) Using visual noise to characterize amblyopic letter identification. J Vis 4(10):904–920

Odom JV et al (2016) ISCEV standard for clinical visual evoked potentials: (2016 update). Doc Ophthalmol 133(1):1–9

Meier K, Giaschi D (2017) Unilateral amblyopia affects two eyes: fellow eye deficits in amblyopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 58(3):1779–1800

Linden ML et al (2009) Thalamic activity that drives visual cortical plasticity. Nat Neurosci 12(4):390–392

Bienenstock EL, Cooper LN, Munro PW (1982) Theory for the development of neuron selectivity: orientation specificity and binocular interaction in visual cortex. J Neurosci 2(1):32–48

Chu BS, Boon MY, Noh DH (2018) Comparing spectacle and toric contact lens prescribing trends for astigmatism. Clin Optom 10:1–9

Brigell M et al (2003) Guidelines for calibration of stimulus and recording parameters used in clinical electrophysiology of vision. Doc Ophthalmol 107(2):185–193

Odom JV et al (2004) Visual evoked potentials standard (2004). Doc Ophthalmol 108(2):115–123

Odom JV et al (2010) ISCEV standard for clinical visual evoked potentials (2009 update). Doc Ophthalmol 120(1):111–119

Bland JM, Altman DG (1986) Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1(8476):307–310

Brecelj J (2003) From immature to mature pattern ERG and VEP. Doc Ophthalmol 107(3):215–224

Cotter SA et al (2006) Treatment of anisometropic amblyopia in children with refractive correction. Ophthalmology 113(6):895–903

Bartlett JW, Frost C (2008) Reliability, repeatability and reproducibility: analysis of measurement errors in continuous variables. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 31(4):466–475

Sharma V, Levi DM, Coletta NJ (1999) Sparse-sampling of gratings in the visual cortex of strabismic amblyopes. Vis Res 39(21):3526–3536

Polat URI, Sagi DOV, Norcia AM (1997) Abnormal long-range spatial interactions in amblyopia. Vis Res 37(6):737–744

Hess RF, Campbell FW, Greenhalgh T (1978) On the nature of the neural abnormality in human amblyopia; neural aberrations and neural sensitivity loss. Pflug Arch 377(3):201–207

Bedell HD, Flom MC (1981) Monocular spatial distortion in strabismic amblyopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 20(2):263–268

Barrett BT, Bradley A, McGraw PV (2004) Understanding the neural basis of amblyopia. Neuroscientist 10(2):106–117

Barrett BT et al (2003) Nonveridical visual perception in human amblyopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 44(4):1555–1567

Blakemore C, Tobin EA (1972) Lateral inhibition between orientation detectors in the cat’s visual cortex. Exp Brain Res 15(4):439–440

Hess RF, Field DJ (1994) Is the spatial deficit in strabismic amblyopia due to loss of cells or an uncalibrated disarray of cells? Vis Res 34(24):3397–3406

Levi DM, Klein SA (1985) Vernier acuity, crowding and amblyopia. Vis Res 25(7):979–991

Watt RJ, Hess RF (1987) Spatial information and uncertainty in anisometropic amblyopia. Vis Res 27(4):661–674

Wilson HR (1991) Model of peripheral and amblyopic hyperacuity. Vis Res 31(6):967–982

Brown AM et al (2015) The contrast sensitivity of the newborn human infant. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 56(1):625–632

Essock EA et al (2003) Oblique stimuli are seen best (not worst!) in naturalistic broad-band stimuli: a horizontal effect. Vis Res 43(12):1329–1335

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr Ranjana Mathur for the collaboration with the Visual Electrophysiology Laboratory at Singapore National Eye Centre and all the colleagues at the Refraction Clinic in KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital for helping with the recruitment of the subjects.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

TP. Yap declares that he has no conflict of interest. C.D. Luu declares that he has no conflict of interest. C.M. Suttle declares that she has no conflict of interest. A. Chia declares that she has no conflict of interest. M.Y. Boon declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study adhered to the tenets of Helsinki and ethical approval was obtained from the Centralised Institutional Review Board (CIRB) (Registration number: R1083/98/2013) at SingHealth and ratified by the human research ethics committees at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia (Approval number: 09364).

Statement of human rights

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Centralised Institutional Review Board at SingHealth, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia, and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments.

Statement on the welfare of animals

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Parents and guardians of the subjects in this study gave their informed consent and children six years of age and above provided assent.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yap, T.P., Luu, C.D., Suttle, C.M. et al. Characterising the orientation-specific pattern-onset visual evoked potentials in children with bilateral refractive amblyopia and non-amblyopic controls. Doc Ophthalmol 142, 197–211 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10633-020-09794-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10633-020-09794-9