Abstract

The inclusion of social and emotional learning (SEL) curricula in preschools may help prevent emotional and behavioral problems. This study evaluated the effects of a SEL curriculum, Strong Start Pre-K, on the social and emotional competence of 52 preschool students using a quasi-experimental, non-equivalent control group design. Teachers rated students’ emotional regulation, internalizing behaviors, and the quality of the student–teacher relationship. Results indicated a significant decrease of internalizing behaviors and more improvement in the student–teacher relationship in the treatment conditions. Results also supported the use of the optional booster lessons contained in the curriculum. Treatment integrity and social validity ratings of Strong Start Pre-K were high. Limitations and implications of this study are addressed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Social and emotional difficulties are common during the preschool years, as young children are just beginning to develop language skills as well as capacities to regulate their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors (Egger and Angold 2006). In addition, changes in families and society are leaving children at greater risk for developing social and emotional problems (Doll and Lyon 1998; Greenberg et al. 2003). Pertinent changes include an increase in numbers of children living in poverty, lack of parent support, changes in family composition, and the decline of traditional social values (Harland et al. 2002; Huaqing Qi and Kaiser 2003).

Children with social and emotional deficits may exhibit difficulty connecting with teachers and classmates, develop internalizing behavior problems (i.e., depression, anxiety, withdrawal), or use physical aggression to convey their needs (Denham and Weissberg 2004; Merrell and Gueldner 2010). Though much attention has focused on children exhibiting externalizing behaviors, such as aggression, much less attention has addressed both the research and practice of interventions for internalizing behaviors. Overlooking children with internalizing problems is common because they are not disruptive; however, if left untreated these children can develop emotional and behavioral disorders with negative long-term outcomes (Merrell 2001). For example, researchers have noted the relationship between internalizing disorders during childhood and later substance abuse problems during adolescence (Compton et al. 2002). Such problematic behaviors warrant adult guidance, intervention, and prevention (DellaMattera 2011). One way to address and potentially prevent such problems is to provide children with early social and emotional learning experiences.

Social and emotional learning (SEL) is the process whereby children are able to acknowledge and manage their emotions, recognize the emotions of others, develop empathy, make good decisions, establish positive friendships, and handle challenges and situations effectively (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning [CASEL] 2003). SEL helps students to recognize emotions first in themselves and then in others so they can also develop empathy. SEL curricula directly teach children appropriate actions and provide a safe environment for them to practice what they learn. A focus of SEL programs is to promote positive behaviors such as success, kindness, and caring and to prevent bullying, violence, and later emotional and behavioral problems (CASEL 2007; Whitcomb 2009). SEL skills can help students and teachers handle themselves, their relationships, and their work more responsibly and more effectively (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning [CASEL] 2007).

SEL works best for children who need it the most, but benefits are also evident in students not considered to be at risk. Findings from a meta-analysis of SEL studies (Payton et al. 2008) indicated that both prosocial behaviors (e.g., good attendance, appropriate classroom behavior, positive attitude toward school) and academic achievement increased significantly, while antisocial behaviors (drug use, violence, and bullying incidents) decreased following SEL interventions. Researchers have also found that the positive effects of SEL typically maintain for at least 6 months following implementation–often longer (Durlak et al. 2011). Elias (2011) stated that all students should receive a minimum of 30 minutes per week of explicit instruction related to SEL as part of their comprehensive Pre-K to 12 educational scope and sequence.

The stability and security of the student–teacher relationship is also foundational to SEL. All children, especially young children, need to form secure, positive attachments with caring adults they can trust (Hyson, 2004). These relationships help foster a sense of well-being in children, a belief that they are safe and of worth. They help children learn to relieve stress, manage anger, and deal with social situations (Denham and Weissberg 2004). Through such relationships, children can also learn to become more empathetic and united, thus better able to work together in classroom learning activities to achieve academic goals (CASEL 2003).

While the practices of SEL are important for students in all grades, early intervention in preschool is particularly beneficial. Preschool is an important period in social and emotional development, as children are beginning to distinguish between positive and negative feelings and are learning how to regulate their emotions (Izard et al. 2004). Unfortunately, social and emotional competence does not always occur automatically, since it is associated with the quality of the early learning environment (Joseph and Strain 2003). Through repeated positive experiences and exposure to SEL, children can learn techniques to manage their emotions, recognize the emotions of others, and get along better with peers (CASEL 2003). SEL programs work more effectively when children directly learn how to initiate appropriate social interactions, develop friendships, and adjust to different social rules and expectations outside of the home (CASEL 2010).

Because preschool children think in concrete rather than abstract terms, SEL curricula work best using concrete methods (Merrell et al. 2009). Young children are better able to understand and learn when they take part in hands-on learning experiences and can actively participate in lessons (Copple and Bredekamp 2009). As they are still developing thought processes and vocabulary, preschool children also have a more difficult time with tasks requiring a substantial amount of interpersonal insight and self-reflection, such as clearly defining their feelings.

Although the majority of SEL programs are for children in kindergarten through 12th grade, some are available for preschool-aged children (see e.g., Domitrovich et al. 2004; Merrell et al. 2009; Petersen 2005; Shure 2001). No one program is practical for every preschool or every child due to different target problems, curricula, and resources available to schools (Merrell and Gueldner 2010). School administrators and teachers must determine which program best fits the needs of their students. A recently developed SEL curriculum, Strong Start Pre-K, may have some advantages over other SEL curricula as it is evidence-based, relatively brief, easy to use, inexpensive, and little prior training is required to implement it (Merrell et al. 2009).

Strong Start Pre-K (Merrell et al. 2009) is part of the Strong Kids program, a series of evidence-based SEL curricula designed to be developmentally appropriate and targeted to reduce students’ internalizing problem behaviors (Merrell and Gueldner 2010). The program includes five grade-specific versions of the curricula covering grades Pre-K through 12. Previous studies of the Strong Kids curricula have demonstrated significant increases in students’ emotional knowledge and prosocial behavior along with decreases in their negative emotional symptoms and internalizing behaviors (see e.g., Caldarella et al. 2009; Feuerborn 2004; Gueldner 2006; Kramer et al. 2010; Merrell et al. 2008). However, there are no published studies of the preschool version of the curriculum.

Strong Start Pre-K (Merrell et al. 2009) is highly structured and partially scripted to cover specific objectives and goals that help to prevent emotional and mental health problems and develop a vocabulary to express feelings. Its lessons are for the specific cognitive, social, and emotional needs of young children, and additional booster lessons are included to reinforce skills that are learned. Children’s literature related to the relevant SEL topic is part of each lesson. A stuffed animal serves as a mascot to help contribute to scenarios. The goal of the curriculum is to promote social and emotional competence, with short, engaging lessons extended by familiar examples and reinforced with repetition and review, while being easy to implement with fidelity.

It is difficult for researchers to know whether practitioners implement a curriculum as designed without treatment fidelity data (Hester et al. 2003). Fidelity includes measuring the content, quality, quantity, and process of treatment implementation (Sanetti and Kratochwill 2009). By measuring treatment fidelity, researchers can discern whether results represent a change actually resulting from the treatment, a flaw in the study design, or a problem with service delivery (Domitrovich et al. 2004).

In addition to fidelity, curricula also need to be socially valid. Social validity refers to the social acceptability of a treatment program, whether resulting behavioral changes are important to clients or consumers of the program (Kazdin 1977). Social validity of an intervention involves examining three components: (1) significance of the goals, (2) appropriateness of procedures, and (3) importance of the outcomes (Wolf 1978). Thus socially valid curricula should reflect goals, procedures, and outcomes of significance to school personnel (Gresham 1983). Social validity data can provide insights into teachers’ willingness to use a curriculum and inform researchers and administrators of the relationship between the program’s effectiveness and teachers’ satisfaction with using it (Hester et al. 2003). Olive and Liu (2005) encourage researchers to make the assessment of social validity a priority in intervention studies.

Although published empirical studies on the effectiveness of other versions of the Strong Kids curricula are available, no published study has yet evaluated Strong Start Pre-K. The particular features of social and emotional competence focused on in this study were increases in peer-related prosocial behaviors and decreases in internalizing behaviors, as has been done in other studies of the Strong Kids SEL curricula (see e.g., Caldarella et al. 2009; Marchant et al. 2010; Kramer et al. 2010). The current study addressed five specific research questions: (1) What effect does the curriculum have on teacher ratings of the social and emotional competence of preschool students? (2) Is an additional effect noted when the booster lessons are taught following the 10-lesson curriculum? (3) Are teachers able to implement the curriculum with fidelity? (4) Do teachers view the curriculum as socially valid? (5) What effect does the curriculum and corresponding booster lessons have on student–teacher relationships?

Method

Participants and Setting

Participants were teachers and students from a Title I preschool in a metropolitan area in Utah. Two female teachers taught the Strong Start Pre-K curriculum (treatment conditions) and two female teachers did not (control condition). One of the teachers was Hispanic and one was Caucasian in each condition. Although the study began with 103 preschool students, 19 moved before the study was completed resulting in 84 who completed the study (50% female, 50% male). Students were from various ethnicities: 66.7% Hispanic, 26.2% Caucasian, 3.6% Mixed Ethnicities, 2.4% African American, and 1.2% Native American. The treatment groups consisted of 52 students; the control group consisted of 32.

Dependent Variables and Measures

The dependent variables in the study consisted of teacher ratings of students’ social and emotional competence, defined as ratings of students’ emotional regulation, internalizing behaviors, and relationship with their teacher. The social and emotional competence of preschool students is difficult to assess through written self-report measures. While a few self-report measures are available, these generally employ an interview-style assessment, which was not feasible given the resource limitations of this study. Therefore, we relied on teachers’ ratings of students’ behaviors. The scales used for these ratings were selected as brief, feasible, reliable, and valid measures, based on the recommendation of a leading researcher in the field of social and emotional assessment of young children (K. W. Merrell, personal communication, April 26, 2010), as well as on the experiences of the researchers. Teachers rated students’ using subscales of the Preschool Behavioral and Emotional Rating Scale (PreBERS; Epstein and Synhorst 2009) and the Preschool and Kindergarten Behavior Scales–Second Edition (PKBS–2; Merrell 2002) as well as the Student–Teacher Relationship Scale (STRS; Pianta 2001).

PreBERS

The first dependent measure consisted of students’ scores on the Emotional Regulation subscale (13 items) from the PreBERS. The normative sample for the PreBERS included 1,471 preschool students from across the nation, ranging from 3 years 0 months to 5 years 11 months in age. Sample items include “Controls anger toward others,” “Reacts to disappointment calmly,” and “Takes turns in play situations.” Teachers respond to these questions using a four-point Likert scale with responses ranging between Not at all like the child (0) to Very much like the child (3). The Emotional Regulation subscale has an internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of .96 (Epstein and Synhorst 2009).

PKBS–2

The second dependent measure consisted of students’ scores on the Internalizing Behavior subscale (15 items) from the PKBS–2. This measure was normed with over 3,300 students from various racial, ethnic, and economic backgrounds. Sample items include “Does not respond to affection from others,” “Has problems making friends,” and “Is afraid or fearful.” Teachers respond on a four-point Likert scale with responses ranging from Never (0) to Often (3). The Internalizing Problems subscale has an internal consistency alpha coefficient of .90 (Merrell 2002).

STRS

The third measure evaluated teachers’ perceptions of their relationships with each of their students using the STRS. The STRS was normed with 275 teachers and 1,535 children ages 4–8 years old (preschool through third grade) from a variety of backgrounds and socioeconomic conditions. It contains 28 items that when summed result in a total score. Individual items fit into one of three relational categories: conflict, closeness, or dependency. Sample items include “This child and I always seem to be struggling with each other,” “I share an affectionate, warm relationship with this child,” and “This child asks for my help when he/she really does not need help.” Teachers respond on a five-point Likert scale with responses ranging from Definitely does not apply (1) to Definitely applies (5). The STRS internal consistency alpha coefficients range from .64 for closeness to .89 for conflict (Pianta 2001).

Independent Variable

The independent variable was the Strong Start Pre-K curriculum (Merrell et al. 2009), which consists of ten lessons and two optional booster session lessons. The curriculum includes a bulletin sent home to parents at the end of each of the ten lessons. The bulletin outlines the contents of the lesson, provides parents with strategies regarding how to reinforce SEL at home, and offers suggestions for books to read with their children. As the school had a high Latino population, a Spanish translation of the bulletin was available to accommodate parents who preferred to receive communications in Spanish.

A researcher was present during implementation of all Strong Start Pre-K lessons to observe and measure treatment fidelity using implementation checklists, as done in other studies of the Strong Kids curricula (e.g. Caldarella et al. 2009; Kramer et al. 2010; Whitcomb 2009). These checklists contain a detailed outline of the objectives and topics defined in the curriculum manual. Two researchers observed ten sessions to calculate inter-rater reliability, which was 80% across these ten sessions.

Procedures

Teachers were randomly assigned to either treatment or control conditions and were given a brief orientation to the study. Teachers and parents provided their informed consent. Treatment teachers then received a one-hour introduction to SEL as well as the Strong Start Pre-K manuals approximately 3 weeks before teaching the first lesson, so they could familiarize themselves with the curriculum and prepare for implementation. All teachers completed the PKBS–2 and PreBERS subscales as well as the STRS on students in their classrooms approximately one week before implementation of the curriculum. Treatment teachers then taught the ten Strong Start Pre-K lessons over a six-week period: approximately two lessons a week at a convenient time, a procedure suggested by Gueldner (2006) and used by Marchant et al. (2010) in studies of the Strong Kids curriculum. At the conclusion of the ten lessons, all teachers completed posttests on the PKBS–2 and PreBERS subscales. Six weeks later one of the treatment teachers also implemented the two optional booster lessons. At the conclusion of the booster lessons, all teachers completed a second posttest using the PKBS–2, PreBERS, and STRS to evaluate the effects of the booster lessons. At this time, treatment teachers also completed a social validity scale.

Social Validity

Social validity was measured using a teacher rating scale derived from Kramer et al. (2010) and Whitcomb (2009) consisting of 18 items. The items are rated on a five-point Likert scale with responses ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5); these are followed by five open-ended questions. Sample items include “A student’s level of social and emotional competence is important to their academic success,” “I feel my students learned important skills from Strong Start,” and “The teaching procedure of the program was consistent with my regular teaching procedures.”

Design and Analysis

This study used a quasi-experimental, non-equivalent control group design (Gall et al. 2007). Although students were not randomly assigned to groups, teachers and their classes were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: treatment, treatment plus boosters, or control. Results from PKBS–2 and PreBERS subscales were analyzed quantitatively using a 3 × 3 split plot analysis of variance (ANOVA) to examine the effects of groups (treatment, treatment plus boosters, and control) across time (pretest, posttest, and follow- up). Scores on the STRS were analyzed using a 3 × 2-split plot ANOVA. Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d. Post hoc power analyses were conducted on statistically non-significant findings using procedures recommended by Onwuegbuzie and Leech (2004). Treatment fidelity and social validity measures were analyzed quantitatively using descriptive statistics (means and percentages). Two members of the research team analyzed the five open-ended social validity questions using check coding (Miles and Huberman 1994), reviewing comments, noting where opinions differed, and discussing differences until arriving at consensus. Teacher response rate across measures and rating intervals was 100%.

Results

Results from the analysis of the Emotional Regulation subscale (PreBERS) scores indicated that, while there was no statistically significant interaction between time and group (F(4, 162) = 1.31, p > .05), there were significant main effects across both group (F(2, 81) = 31.06, p < .001) and time (F(2, 162) = 44.27, p < .001). There was a slight but statistically significant increase in emotional regulation scores for each of the three experimental conditions with moderate to large effect sizes (see Table 1). Despite the moderate to large effect sizes in each condition, the interaction between time and group had low statistical power (i.e., .40). No additional effect was associated with implementation of the booster lessons.

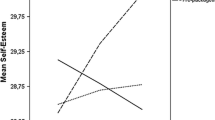

Results from the analysis of the Internalizing Behaviors subscale (PKBS–2) scores indicated that there was a statistically significant interaction between time and group (F (4, 162) = 5.08, p = .001). The main effects for both time (F (2, 162) = 29.92, p < .001) and group (F (2, 81) = 66.73, p < .001) were also statistically significant. While the treatment group showed the greatest reduction in internalizing behaviors initially, the treatment group plus boosters had the greatest reduction over time with a very large effect size (see Table 2). There was no statistically significant change in PKBS-2 scores for the control group.

Results from the analysis of the total score on the STRS indicated a statistically significant interaction between time and group (F (2, 81) = 5.92, p < .05).While the total score increased in all of the experimental conditions, only in the treatment plus boosters group was this increase statistically significant (see Table 3). There was also a statistically significant interaction between time and group on the measure of conflict (F (2, 81) = 6.38, p < .01) with the two treatment conditions showing a decrease and the control group showing an increase. While there was no significant interaction between time and group on the measure of closeness (F (2, 81) = 1.91, p > .05), there was a main effect for group (F (2, 81) = 23.61, p < .01). Each group showed improvement in closeness, with the treatment plus boosters group showing the greatest improvement. The observed power for the interaction between time and group was low (i.e., .39). Finally, there was a significant interaction between time and group on the measure of dependency (F (2, 81) = 5.36, p < 0.05. The treatment group increased in dependency, while the treatment plus boosters and control conditions both decreased.

Results of the treatment fidelity observations indicated that teachers implemented 90% of the Strong Start Pre-K lesson components indicated in the curriculum manual, but did not implement 10% of the components. The sections most often omitted included the review of the previous lesson, introduction to the new lesson, and conclusion of the lesson.

Teachers agreed (indicated agreed or strongly agreed) with 64% of the items on the social validity questionnaire and were neutral on 36% of the items: No items received ratings of disagree or strongly disagree. Items were sorted into three categories regarding the program’s goals, procedures, and outcomes. The goals of the program received an acceptability rating of 4.2 (SD = 0.40) on the five-point Likert scale. The procedures received a score of 3.68 (SD = 0.44), and the outcomes received a score of 3.59 (SD = 0.29). Written comments indicated that teachers felt that the lessons were somewhat long for their students, and they were not always sure how well students liked the curriculum. Teacher comments included that, after instruction in the curriculum, students seemed to get along better with their peers and were able to use words rather than negative actions to express themselves. Both treatment teachers reported that they would recommend the use of Strong Start Pre-K to other preschool teachers.

Discussion

This study examined the effects of Strong Start Pre-K on teacher ratings of preschool students’ social and emotional competence (specifically students’ emotional regulation and internalizing behaviors), as well as possible further change resulting from the curriculum’s optional booster sessions. Additional assessment examined whether preschool teachers were able to implement Strong Start Pre-K with fidelity and whether they viewed the curriculum as socially valid. Finally, this study investigated the effects of Strong Start Pre-K on student–teacher relationships.

Across all conditions, including the control condition, teachers noted an increase in students’ emotional regulation. These results suggest that improvements in students’ emotional regulation occurred through their experiences in the classroom with teachers and peers. This aligns with theory and research on childhood social development, as preschool is a time of growth and development where “many new social and emotional skills are first being developed, tried, and tested outside the home with both peers and teachers” (Voegler-Lee and Kupersmidt 2011, pp. 606–607). Accordingly, we hypothesize that the improvement in the emotional regulation of all students may be due to their natural, normal, socio-emotional development as they matured and learned to navigate peer relationships in their preschool environment.

Teachers’ ratings of students’ internalizing behaviors decreased significantly after implementation of Strong Start Pre-K. Similar decreases in internalizing behaviors have been found in other studies of the Strong Kids curricula (see e.g., Caldarella et al. 2009; Kramer et al. 2010; Whitcomb 2009). This could have important implications as internalizing symptoms are best addressed at an early age (Durlak and Wells 1997). An intervention such as Strong Start Pre-K could provide the needed help for at-risk preschool students without having to individually identify and treat them.

While a favorable decrease in internalizing behaviors occurred in both treatment conditions, significantly more improvement was evident in the treatment group that received the booster lessons. This suggests that the additional reinforcement of the curriculum in the booster lessons is quite beneficial and worth the extra effort. We recommend that preschool teachers take the additional time to teach the booster lessons at the conclusion of the 10-lesson curriculum.

The overall perceptions of the student–teacher relationships improved in all conditions, likely due to students and teachers getting to know each other over time. However, the change in the total score of the classroom that received Strong Start Pre-K plus booster lessons indicated the most improvement. When examining the specific categories that make up the total student–teacher relationship score, the level of conflict decreased significantly in both of the treatment classrooms, particularly in the treatment classroom that added the booster lessons, while the level of conflict actually increased in the control classroom. In addition, the level of closeness appeared to improve over time in all experimental conditions. These results are promising, as much research has noted the importance of positive relationships with adult figures in the life of children (Hamre and Pianta 2001). In their review of research, Voegler-Lee and Kupersmidt (2011) noted that building positive relationships with children is a fundamental component of SEL. As students develop close, caring relationships with teachers, relationships that are void of major conflict, they are better able to work toward regulating their emotions in a safe environment as well as achieving academically and socially (see Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning [CASEL] 2010). Consequently, we recommend that training teachers to deliver effective SEL programs include an emphasis on building and maintaining positive relationships with students through the appropriate use of praise, attention, and encouragement.

Interestingly, in the treatment group that did not receive booster lessons there was an increase in the STRS category of student dependency. This category measures the degree a teacher perceives a student to be overly dependent and can indicate a perceived problem of overreliance on the teacher. We are unclear why students in this treatment group increased in dependency, while students in the treatment group that received booster lessons did not. More study is necessary to understand these findings.

Results were favorable in the area of treatment fidelity: It appeared feasible for the teachers to implement Strong Start Pre-K as designed. Results indicated that teachers were able to implement the core components of the curriculum with little prior training. However, the teachers in the current study tended to skip the reviews and conclusions included in the lessons. The reason for these components with partial and non-implementation may have been insufficient time; teachers did report that some of the lessons were too lengthy for their students. Similar treatment fidelity results were evident in studies of Strong Start K-2 (Caldarella et al. 2009; Kramer et al. 2010). Teachers did not receive treatment fidelity data during this study, nor was any feedback on lesson presentation provided. To improve teacher training and potentially student outcomes, future researchers and practitioners may consider sharing fidelity feedback after observations, particularly while teachers are first learning the curriculum.

Social validity results were also favorable, indicating that the teachers generally supported the goals, procedures, and outcomes of the curriculum. Teachers reported being confident in their ability to implement the curriculum and considered Strong Start Pre-K to be a good way to help prevent preschool students’ social and emotional problems. The finding that the teachers generally liked the curriculum but felt that some of the lessons were too long for some of their students was similar to teacher feedback on studies of Strong Start K-2 (Caldarella et al. 2009; Kramer et al. 2010). This similarity suggests that teachers of young children may want to divide the lessons and teach them over two sessions rather than one, or read the book at a separate point in the day to reinforce the skills discussed in the lesson. Overall, the teachers were pleased with Strong Start Pre-K and were willing to teach the curriculum again.

Although results of this study were generally favorable, there were some limitations. One limitation was that the researchers could not alter the classroom placement of students nor randomize which students received the curriculum and which did not. Another limitation was the small sample size (only two treatment teachers and two control teachers) and low statistical power for some analyses, suggesting the need for further studies using larger samples. In addition, as the teachers were both the service providers and the raters of change, there may have been some bias in their ratings. Finally, while the social validity measure included a variety of questions about the curriculum’s goals, procedures, and outcomes along with open-ended questions, an interview component was not included in the measure.

The Strong Start Pre-K manual provides suggestions for teachers to integrate and reinforce the SEL skills taught throughout classroom instruction to increase generalization and maintenance of skills. However, we did not assess for such integration and reinforcement in this study. More student improvement would likely occur if teachers encouraged students to use the SEL skills in other aspects of their school routines, rather than stress application only during lesson time. These are areas worthy of further study.

Future research could include additional measures of change from either parent rating scales or direct observations of student behavior. Future studies could also evaluate the effectiveness of the home bulletin which solicited parental involvement in reinforcing the SEL skills at home, emphasizing ways to integrate SEL within families and home contexts. Additionally, more research would be helpful regarding the lasting effects of Strong Start Pre-K in preventing and reducing internalizing behaviors over time. It would also be advantageous to have a larger study with more teachers implementing the curriculum.

This first published study evaluating Strong Start Pre-K yielded promising results in improving social and emotional competence in preschool students. Teachers found that the curriculum had value in teaching SEL skills. Strong Start Pre-K was also feasible to implement with few additional resources. The curriculum appears useful and beneficial for preschool classrooms, though there is a need for additional research. The findings in this study contribute to the emerging body of research support for SEL in preschools and for the Strong Kids curriculum series.

References

Caldarella, P., Christensen, L., Kramer, T. J., & Kronmiller, K. (2009). Promoting social and emotional learning in second grade students: A study of the strong start curriculum. Early Childhood Education Journal, 37(1), 51–56. doi:10.1007/s10643-009-0321-4.

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning [CASEL]. (2003). Safe and sound: An educational leader’s guide to evidence-based social and emotional learning (SEL) programs. Chicago, IL: Author.

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning [CASEL]. (2007). Youth and schools today: Why SEL is needed. Chicago, IL: Author.

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning [CASEL]. (2010, March 18). Congressman Ryan discusses early college and social and emotional learning with Secretary Duncan [video file]. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_PTZcty1G5A.

Compton, S. N., Burns, B. J., Egger, H. L., & Robertson, E. (2002). Review of the evidence base for treatment of childhood psychopathology: Internalizing disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 1240–1266.

Copple, C., & Bredekamp, S. (2009). Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood programs: Serving children from birth to age 8 (3rd ed.). Washington, D.C.: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

DellaMattera, J. N. (2011). Perceptions of preservice early educators: How adults support preschoolers’ social development. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 32(1), 26–38. doi:10(1080/10901027),2010,547654.

Denham, S. A., & Weissberg, R. P. (2004). Social-emotional learning in early childhood: What we know and where to go from here. In E. Chesebrough, P. King, T. P. Gullota, & M. Bloom (Eds.), A blueprint for the promotion of prosocial behavior in early childhood (pp. 13–51). New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Doll, B., & Lyon, M. A. (1998). Risk and resilience: Implications for the delivery of educational and mental health services in schools. School Psychology Review, 27(3), 348–363.

Domitrovich, C. E., Greenberg, M. T., Kusché, C. A., & Cortes, R. (2004). The PATHS (Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies) Preschool curriculum. South Deerfield, MA: Channing-Bete.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x.

Durlak, J. A., & Wells, A. M. (1997). Primary prevention mental health programs for children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. American Journal of Community Psychology, 25, 115–152. doi:10.1023/A:1024654026646.

Egger, E. L., & Angold, A. (2006). Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: Presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 313–337. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01618.x.

Elias, M. J. (2011, May 12). Why should the ESEA systematically include social-emotional and character development as essential for students’ academic and life success? Presentation at a Congressional Briefing, Senate Office Building, Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://www.nasponline.org/advocacy/news/2011/may/Maurice_Elias_presentation_slides.pdf.

Epstein, M. H., & Synhorst, L. (2009). PreBERS: Preschool Behavioral and Emotional Rating Scale, examiner’s manual. Austin, Texas: Pro-Ed.

Feuerborn, L. L. (2004). Promoting emotional resiliency through classroom instruction: The effects of a classroom-based prevention program. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Oregon, Eugene. Retrieved from http://strongkids.uoregon.edu/research.html.

Gall, M. D., Gall, J. P., & Borg, W. R. (2007). Educational research: An introduction (8th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon.

Greenberg, M. T., Weissberg, R. P., O’Brien, M. U., Zins, J. E., Fredericks, L., Resnik, H., et al. (2003). Enhancing school-based prevention and youth development through coordinated social, emotional, and academic learning. American Psychologist, 58(6/7), 466–474. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.58.6-7.466.

Gresham, F. M. (1983). Social validity in the assessment of children’s social skills: Establishing standards for social competency. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 1(3) , 299–307. doi:10.1177/073428298300100309.

Gueldner, B. A. (2006). An investigation of the effectiveness of a social-emotional learning program with middle school students in a general education setting and the impact of consultation support using performance feedback. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Oregon, Eugene). Retrieved from http://strongkids.uoregon.edu/research.html.

Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2001). Early teacher-child relationships and the trajectory of children’s school outcomes through eighth grade. Child Development, 72(2), 625–638. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00301.

Harland, P., Rijneveld, S. A., Brugman, E., Verloove-Vanhorick, S. P., & Verhulst, F. C. (2002). Family factors and life events as risk factors for behavioural and emotional problems in children. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 11, 176–184. doi:10.1007/s00787-002-0277-z.

Hester, P. P., Baltodano, H. M., Gable, R. A., Tonelson, S. W., & Hendrickson, J. M. (2003). Early intervention with children at risk of emotional/behavioral disorders: A critical examination of research methodology and practices. Education and Treatment of Children, 26(4), 362–381.

Huaqing Qi, C., & Kaiser, A. P. (2003). Behavior problems of preschool children from low-income families: Review of the literature. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 23(4), 188–216. doi:10.1177/02711214030230040201.

Hyson, M. (2004). The emotional development of young children (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Teachers College, Columbia University.

Izard, C. E., Trentacosta, C. J., King, K. A., & Mostow, A. J. (2004). An emotion-based prevention program for Head Start children. Early Education and Development, 15(4), 407–422. doi:10.1207/s15566935eed1504_4.

Joseph, G. E., & Strain, P. S. (2003). Comprehensive evidence-based social-emotional curricula for young children: An analysis of efficacious adoption potential. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 23(2), 65–76. doi:10.1177/02711214030230020201.

Kazdin, A. E. (1977). Assessing the clinical or applied importance of behavior change through social validation. Behavior Modification, 1(4), 427–452. doi:10.1177/014544557714001.

Kramer, T. J., Caldarella, P., Christensen, L., & Shatzer, R. H. (2010). Social-emotional learning in kindergarten classrooms: Evaluation of the Strong Start curriculum. Early Childhood Education Journal, 37(4), 303–398. doi:10.1007/s10643-009-0354-8.

Marchant, M., Brown, M., Caldarella, P., & Young, E. (2010). Effects of strong kids curriculum on students at risk for internalizing disorders: A pilot study. Journal of Empirically Based Practices in Schools, 11(2), 123–143.

Merrell, K. W. (2001). Helping students overcome depression and anxiety: A practical guide. New York: The Guilford Press.

Merrell, K. W. (2002). Preschool and Kindergarten Behavior Scales, 2 nd Edition, examiner’s manual. Austin, Texas: Pro-Ed.

Merrell, K. W., & Gueldner, B. A. (2010). Social and emotional learning in the classroom: Promoting mental health and academic success. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Merrell, K. W., Juskelis, M. P., Tran, O. K., & Buchanan, R. (2008). Social and emotional learning in the classroom: Evaluation of Strong Kids and Strong Teens on students’ social-emotional knowledge and symptoms. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 24, 209–224. doi:10.1080/15377900802089981.

Merrell, K. W., Whitcomb, S. A., & Parisi, D. M. (2009). Strong Start Pre-K: A social & emotional learning curriculum. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

Miles, H. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). An expanded sourcebook: Qualitative data analysis (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Olive, M. L., & Liu, Y.-J. (2005). Social validity of parent and teacher implemented assessment-based interventions for challenging behavior. Educational Psychology, 25(2–3), 305–312. doi:10.1080/0144341042000301229.

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Leech, N. L. (2004). Post hoc power: A concept whose time has come. Understanding Statistics, 3(4), 201–230. doi:10.1207/s15328031us0304_1.

Payton, J., Weissberg, R. P., Durlak, J. A., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., Schellinger, K. B., et al. (2008). The positive impact of social and emotional learning for kindergarten to eighth-grade students: Findings from three scientific reviews. Chicago, IL: Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning.

Petersen, K. S. (2005). Safe and caring schools: Skills for school, skills for life. Champaign, IL: Research Press.

Pianta, R. C. (2001). Student-Teacher Relationship Scale: Professional Manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resource.

Sanetti, L. M. H., & Kratochwill, T. T. (2009). Toward developing a science of treatment integrity: Introduction to the special series. School Psychology Review, 38(4), 445–459. doi:10.1037/a0015431.

Shure, M. B. (2001). I Can Problem Solve (ICPS): An interpersonal cognitive problem solving program (Preschool). Champaign, IL: Research Press.

Voegler-Lee, M. E., & Kupersmidt, J. B. (2011). Intervening in childhood social development. In P. K. Smith & C. H. Hart (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of childhood social development (2nd ed., pp. 605–626). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Whitcomb, S. A. (2009). Strong Start: Impact of direct teaching of a social emotional learning curriculum and infusion of skills on emotion knowledge of first grade students. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Oregon, Eugene). Retrieved from http://strongkids.uoregon.edu/research.html.

Wolf, M. (1978). Social validity: The case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 11(2), 203–214. doi:10.1901/jaba.1978.11-203.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gunter, L., Caldarella, P., Korth, B.B. et al. Promoting Social and Emotional Learning in Preschool Students: A Study of Strong Start Pre-K . Early Childhood Educ J 40, 151–159 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-012-0507-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-012-0507-z