Abstract

The present study examined how the dosage and quality of the federal preschool program “Head Start” (HS) in the US related to children’s self-regulation skills in kindergarten. Using Propensity Score Matching and multiple regression (OLS), this study explored how the number of years and hours a week of HS were related to self-regulation among 2,383 children, who entered the program either at 3 or 4 years old. An additional year in HS was significantly positively associated with self-regulation in kindergarten, while the number of hours a week in HS was not. However, the quality of teacher–child interactions moderated the relation between hours a week in HS and self-regulation. Findings contribute to the growing body of evidence about how dosage and quality of early childhood education experiences relate to children’s development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Self-regulation is defined broadly as the capacity to monitor and regulate behavior, emotion, and cognition to accomplish goals, adapt to specific cognitive and social demands, and develop markedly during preschool. Self-regulation encapsulates a multidimensional set of skills (Weissberg et al., 2015) associated with success in school, health, and well-being (Moffitt et al., 2011; Ursache et al., 2012). Importantly, the quality of children’s preschool experiences plays a formative role in self-regulation development, serving as a crucial and malleable opportunity to foster this critical skill (Morris et al., 2013; Raver et al., 2008).

However, less is known about the effects of the dosage of preschool experience on the development of self-regulation. Studies report mixed evidence regarding associations between preschool dosage (e.g., number of hours a day, years, attendance) and self-regulation-related skills. Some studies, for example, indicate that children enrolled more hours a week in preschool performed more poorly on socioemotional outcomes associated with self-regulation (e.g., Huston et al., 2015; McCartney et al., 2010). On the other hand, research examining the number of years that children attend preschool presents mostly positive relations to child academic and socioemotional outcomes that encompass regulation (e.g., Moore et al., 2015; Wen et al., 2012).

Given the mixed evidence regarding the dosage of preschool experiences on the development of socio-emotional skills and considering self-regulation as a core competency involved in the development of socio-emotional skills (Weissberg et al., 2015), the next step is to examine under which conditions more years and hours in preschool can be beneficial for the development of self-regulation. Evidence about the importance of quality of early childhood experience would suggest that more years and more hours of preschool should be helpful only if these are of adequate quality (McCartney et al., 2010). However, this specific question has yet to be examined. The present study addresses this gap by examining the relation between two forms of preschool dosage, the number of hours a week and years of attendance, with self-regulation in kindergarten, and the moderation role quality of experiences may play.

Self-Regulation: A Core Component of Children’s Development

Self-regulation is a multidimensional construct with three overlapping and interrelated domains: Cognitive, Emotional, and Behavioral (Berger et al., 2007; Calkins & Williford, 2009; Murray et al., 2015). Cognitive self-regulation includes focusing and redirecting attention, having cognitive flexibility, and inhibiting impulses, skills that often fall under the domain of Executive Functions (Halle & Darling-Churchill, 2016). Emotional self-regulation is managing and modulating strong or unpleasant feelings, which partly relies on cognitive regulatory processes such as inhibitory control (Calkins, 1997). Both cognitive and emotional self-regulation are important for exerting behavioral regulation (Blair & Dennis, 2015), which is the ability to organize and monitor behavior, including compliance to adult demands and directives, delaying gratification, and inhibiting impulsive responses (Kuczynski & Kochanska, 1995). Skills such as persistence and organizing cognitive skills to solve problems and direct behavior towards a goal are also part of behavioral self-regulation (Berger, 2011, 2015; Murray et al., 2015; Smith-Donald et al., 2007).

Cognitive self-regulation skills in preschool have been found to predict a range of academic outcomes (e.g., Edossa et al., 2018; Malanchini et al., 2018; Ponitz et al., 2009), with a strong association with mathematic performance (Espy, 2004; Lenes et al., 2020). For example, the Chicago School Readiness Project (CSRP) experimental study found that children assigned to a comprehensive intervention service aimed at supporting children’s self-regulation displayed significant increases in executive functions in comparison to the control group and that these mediated gains in vocabulary, letter-naming and early math skills (Raver et al., 2011). On the other hand, behavioral self-regulation predicts a range of academic (e.g., Backer-Grøndahl et al., 2019; Edossa et al., 2018; Ponitz et al., 2009) and social and behavioral outcomes (e.g., Blair & Raver, 2015; Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2009).

Several studies have found that better self-regulation skills lead to children’s gains in socio-emotional and academic outcomes (Robson et al., 2020). Additionally, higher levels of self-regulation seem to have clear differential benefits for children in high-poverty families and schools (Acar et al., 2021; Blair & Raver, 2015; Raver et al., 2011). Importantly, these studies indicate the malleability of self-regulatory skills and that a high-quality ECE environment can affect the development of self-regulation. Thus, findings suggest the need to examine the necessary conditions more closely under which preschool may affect children’s self-regulation development.

The Role of Preschool Dosage and Children’s Development

Predominant conceptualizations of preschool dosage include attendance/absenteeism, the number of hours a week, and attending one versus two preschool years. Greater attendance (e.g., Ansari & Purtell, 2018; Ehrlich et al., 2018; Xue et al., 2016) and more years (two versus one) of preschool (e.g., Shah et al., 2017) have been associated with increases in academic and behavioral outcomes. However, preschool dosage studies examining hours a week have shown mixed associations to child outcomes. Some studies have shown that children who spend more hours in center care settings are more academically ready in kindergarten (Skibbe et al., 2011) and have higher math and preliteracy scores (Fuller et al., 2017). Nevertheless, other studies have found that children who attend more preschool hours display bigger behavioral problems than their peers who have attended fewer hours a day (Huston et al., 2015; McCartney et al., 2010).

Multiple studies found that students who attend two years of preschool have significantly stronger literacy and numeracy skills than those who attend only one year (e.g., Infurna & Montes, 2020; Reynolds et al., 2011; Xue et al., 2016). Studies examining the difference between attending two versus one year, specifically at Head Start (HS), the US federal preschool program, have shown mixed results. The Impact Study (Puma et al., 2012), for example, found that those who attended for two years (beginning at three years of age) showed almost no significant differences compared to the cohort who started HS at four years of age, except for higher scores in parent-reported measures of socioemotional skills and positive approaches to learning, by third grade. Other studies, however, have found evidence of positive associations between an additional year of HS and child academic (e.g., Infurna & Montes, 2020; Xue et al., 2016; Youn, 2016) and socioemotional outcomes in kindergarten (e.g., Moore et al., 2015; Wen et al., 2012).

Specific to regulation and behavior, some studies have found negative effects on social competence and behavior of starting preschool earlier (Loeb et al., 2007; McCartney et al., 2010), while others have seen some positive effects (Moore et al., 2015; Wen et al., 2012). For example, Loeb et al. (2007) found that children spending more than 30 h weekly in a center care setting had lower self-control and higher externalizing behavior. Magnuson et al. (2007), however, found that the negative associations did not hold for children in Head Start centers. Nevertheless, a recently randomized control trial of full versus half-day preschool programs showed that the full-day produced substantial and positive effects on children’s academic outcomes but also on teacher-reported measures of socioemotional development. At kindergarten entry, children offered full-day continued to outperform peers on an estimate of basic literacy (Atteberry et al., 2019).

The Moderation Role of Classroom Quality

One hypothesis that could explain the mixed evidence on preschool dosage and socioemotional outcomes is that the experience might also need to be of a certain quality for more dosage to be beneficial. The current study uses the Teaching Through Interactions (TTI) framework as a foundation to understand quality. Empirical research in the United States and worldwide using the Teaching Through Interactions (TTI) framework (Hamre & Pianta, 2007) has identified associations between specific types of teacher–child interactions and children's socio-emotional, cognitive, and academic development (e.g., Burchinal et al., 2016; Cadima et al., 2010; Leyva et al., 2015). Moreover, the nature of teacher–child interactions appears particularly important for children from low-income backgrounds (e.g., Curby et al., ; Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Hatfield et al., 2012). A meta-analysis examining preschool quality features found that teacher–child interactions were a stronger predictor of child outcomes than other general quality measures in low-income contexts (Burchinal et al., 2016). Further, experimentally controlled studies indicate that students in classrooms characterized by high-quality teacher–child interactions contributed to children developing higher executive function (Araujo et al., 2014; Kane et al., 2013).

The TTI framework classifies teacher–child interactions in preschool into three domains. The first, Emotional Support, refers to positive communication and affect in the classroom, sensitivity, and responsiveness to children's needs, and regard for students' perspectives. The second, classroom organization, refers to teachers' ability to proactively manage children's behavior, engage children in interesting activities, and organize the time in the classroom. Lastly, Instructional support involves engaging children in higher-order thinking activities (Hamre et al., 2013).The only study that, to our knowledge, has examined classroom interaction quality as a moderator between preschool dosage and child outcomes found that the quality of classroom experiences did not moderate the effects of dosage on academic outcomes (Xue et al., 2016). However, this study found no associations between one additional year of preschool and teacher-reported social outcomes for children attending Head Start.

The Present Study

Research on preschool dosage has shown a positive association between attending more preschool years and academic outcomes. Nevertheless, the benefits of preschool attendance for socioemotional outcomes such as self-regulation are less clear. Furthermore, the quality of teacher–child interactions as a moderator of dosage has yet to be explored. The present study addresses these issues by examining how children’s self-regulation skill development is associated with dosage and whether the quality of teacher–child interactions moderates the association in a nationally representative sample of children enrolled in Head Start. Specifically, we organized the research questions according to two preschool dosage measures:

-

1.

Preschool dosage as the number of years that children attend HS (one versus two years)

-

1a.

What is the relation between the number of years children attend HS and self-regulation in kindergarten?

-

1b.

Does the quality of teacher-child interactions moderate the relation between the number of years in HS and self-regulation?

-

1a.

-

2.

Preschool dosage as the number of hours a week that children attend HS

-

2a.

What is the relation between the number of hours a week that children attend HS and self-regulation in kindergarten?

-

2b.

Does the quality of teacher-child interactions moderate the relation between the number of hours a week and self-regulation?

-

2a.

We hypothesize that: (1) Children that attend two years of Head Start will have significantly better self-regulatory skills by the spring of kindergarten than those who attend one year. Moreover, there will be a significant moderation of teacher–child interaction quality. In other words, the benefits of attending a second year will be greater for children in classrooms with a higher quality of teacher–child interactions. (2) It is less clear whether more hours a week will be beneficial, considering prior evidence about non-academic outcomes. However, more hours a week may have a positive and stronger association with self-regulation in kindergarten when children are in classrooms with a higher quality of teacher–child interactions.

Methods

Participants

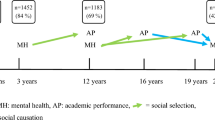

The present study used data from the Family and Children Experiences Survey (FACES, 2009), which followed children attending Head Start when they were three and four years old until kindergarten. The cohort structure under analysis is shown in Fig. 1. The sample represents the population of children who entered Head Start in the fall of 2009, excluding children already in their second year (estimated to be approximately 30% of the Head Start population). It includes 60 programs, with two centers per program, up to three classrooms per center, 486 classrooms, and 2,383 children across all programs in fall 2009. The data includes four waves of data collection: fall and spring of children’s first Head Start year, spring of the second Head Start year for children in the 3 years old cohort, and spring of the children’s kindergarten year.

Measures

Self-Regulation in this study utilized a direct and composite of teacher-reported measures of a child’s behavioral self-regulation. The Pencil Tap (Smith-Donald et al., 2007) is a direct measure adapted from the peg tap (Diamond & Taylor, 1996). In this test, the child is asked to do the opposite of what the assessor does, tap with the pencil once when the assessor taps twice, and vice versa. Pencil Tap objectively assesses children’s cognitive self-regulation, specifically inhibitory control, which relates to young children’s development in mathematics, vocabulary, and literacy (Blair & Razza, 2007; Espy et al. 2004; McClelland et al., 2007). Children were assessed on the Pencil Tap for each time point for the four-year-old cohort and the second through the fourth timepoint for the three-year-old cohort. The measure had internal reliability of 0.82 in preschool and 0.75 in kindergarten. This variable was transformed into a categorical variable to deal with the negative skewness of its distribution in this sample (skewness =|2.24|). The transformed variables included three categories: low-range (under 60% of correct responses), mid-range (between 60 and 89% of correct answers), and high-range (90% or more correct responses).

Teacher-reported self-regulation comprised the Approaches to Learning scale and the Problem Behavior scale. Approaches to Learning (U.S. Department of Education, 2002) assesses a child’s motivation, attention, organization, persistence, and independence in learning. The scale has established reliability (Cronbach alpha = 0.89) and demonstrated relations with elementary school academic achievement (Duncan et al., 2007). The Problem Behaviors scale is an abbreviated adaptation of the Personal Maturity Scale (Entwisle et al., 1987) and the Behavior Problems Index (BPI, Peterson & Zill, 1986). It measures negative child behaviors associated with learning problems and later grade retention. This scale was inversed before being standardized. Items in both scales were inter-correlated at an alpha level of 0.90. The Teacher-reported self-regulation composite was created by standardizing scores and averaging across both scales.

Classroom Quality was measured using The Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS; Pianta et al., 2008). CLASS is a validated classroom observation tool that assesses teacher–child interactions across ten dimensions. Previous research demonstrates that these dimensions are organized into three broad domains (Hamre et al., 2014): Emotional Support, Classroom Organization, and Instructional Support. Each domain includes dimensions scored on a 7-point scale, with 1–2 representing low scores, 3–5 representing moderate scores, and 6–7 representing high scores. This study used a bifactor approach to interpret the CLASS, which presents a revised conceptualization of the CLASS scores that have been previously validated and shown to fit better the data than the three-domain factor solution (Hamre et al., 2014; Reise et al., 2010). We used Mplus 7.4 to fit the bifactor model of the CLASS, as shown in Fig. 2. The orthogonal factor scores created in the bifactor model were imported into Stata 14. SE, and examined concurrently in the predictive models for each outcome. The model showed adequate fit to the sample based on analyzed fit statistics and a better fit than the traditional 3-domain solution (see Table 1).

Children and Families Socio-demographic characteristics: At baseline (fall 2009), parents answered a survey about their socio-demographic characteristics (such as race, ethnicity, and age), their context (such as household size, poverty, if parents were working), and activities at home (such as reading books, time spent watching tv). They also answered questions about their children’s socio-demographic characteristics. These variables were used as covariates (see Table 2).

Methodological Considerations in the Study of Dosage and Child Outcomes

A challenge in studying the effects of preschool experiences, such as dosage or quality, is the absence of randomization on key variables of interest. Propensity Score Matching is a commonly used statistical approach to minimize selection bias and improve the ability to make causal inferences from non-randomized studies of preschool dosage (PSM; Rosenbaum & Rubin, 1984). PSM is a method that can significantly reduce selection bias and provide more robust estimates by matching participants with comparable demographic and other pre-treatment characteristics on their probability to participate in the treatment independently of their actual participation in treatment (Cook et al., 2002). PMS has become one of the preferred methods of researchers studying the dosage of preschool and child outcomes in non-randomized samples (see Domitrovich et al., 2013; Wen et al., 2012; Youn, 2016).

Analytic Plan

To examine the number of years as dosage, we used PMS. Also, we conducted an Ordinary-Least-Squares (OLS) linear regression replicating the PSM models as a sensitivity test. We used OLS regression models to examine the number of hours weekly as dosage and the moderation analysis. All analyses were conducted using Stata/SE 14.2

Sample Matching Process

We classified covariates into parent/family context, child-level, and program/teacher level. We examined all existing variables in each of these categories and selected variables that are the most relevant from a theoretical perspective. All covariates were measured at baseline (Fall 2009). See Table 2 for a list of the covariates and their descriptive statistics.

PSM analyzes were conducted using the nearest-neighbor matching technique with replacement and a caliper of 0.1 (Stuart, 2010). Only those with a close match were included in this set of analyses, referred to as the Region of Common Support (Harder et al., 2010). The Region of Common Support included 1653 children, excluding 730 children from the whole sample who had no match (see Table 3). Once the samples were matched, and adequate balance was achieved (see Table 4), outcomes variables were added back to the data set and estimated the effects of two versus 1 year of HS, including the full range of covariates in the model to adjust for any potential remaining bias (Coley & Lombardi, 2013). To address missing data issues, we used multiple imputation and imputed 20 data sets using the chained-equations method (White et al., 2011). We accounted for the nesting of children in classrooms by using robust standard errors clustered at the classroom level.

Results

To address our research questions, the first model included the main effects of dosage and quality variables and the covariates on self-regulation. Each outcome variable was examined on a separate model: teacher-reported behavioral self-regulation and the direct measure of cognitive self-regulation. The second model included main effects and interaction terms between the two main dosage variables (number of years and number of hours a week) and the CLASS factors to examine how the quality of classroom experiences moderated the relation between dosage and self-regulation.

Impact of Number of Years of HS Attendance and Moderation by Teacher–Child interactions Quality

For the first model examining cognitive self-regulation as a function of the amount and quality of HS experiences, Propensity Score Matching (PMS) results showed that dosage and quality predicted 17% of the variance in the outcome. Results indicated that a larger number of years in HS was positively associated with cognitive self-regulation in kindergarten, as measured by pencil tap (R2 = 0.17, F(38, 355.3) = 1.70, p < 0.01). Children’s pencil tap score increased 0.23 points for the additional year in HS. Teacher-reported behavioral self-regulation was also significantly associated with the number of years in HS (R2 = 0.26, F(38, 385.4) = 5.07, p < 0.01). Teachers reported children’s behavioral self-regulation increased by 0.32 standard deviations for an additional year in HS (see Table 5).

Multiple linear regression (OLS) results confirmed what was found in PMS. A larger number of years in HS was positively associated with cognitive self-regulation in kindergarten, as measured by pencil tap (R2 = 0.14, F(38, 350.4) = 2.42, p = 0.001). Children’s pencil tap score increased by 0.20 points for the additional year in HS after controlling for age at assessment and baseline characteristics. Teacher-reported behavioral self-regulation was also significantly associated with the number of years in HS (R2 = 22, F(40, 405.3) = 9.94, p < 0.001). Teachers reported children’s self-regulation increased by 0.3 standard deviations for an additional year in HS, ceteris paribus (see Table 5).

The second model examined the quality of teacher–child interactions in HS as a moderator between the amount of HS experiences (dosage) and self-regulation (cognitive and behavioral) in kindergarten. Results from PMS showed that the cognitive facilitation factor of quality of teacher–child interactions marginally moderated the relation between the number of years in HS and the teacher-reported measure of self-regulation (p = 0.06), ceteris paribus. No other significant interactions were found for the number of years.

Impact of Hours a Week in HS Attendance and Moderation with Teacher–Child Interactions Quality

We use OLS results to examine the relation between hours a week and self-regulation. Results showed that the number of hours a week in HS was not significantly associated with cognitive or teacher-reported behavioral self-regulation. However, there was a significant interaction between the number of hours a week and Responsive Teaching (R2 = 0.14, F(44, 364.7) = 2.30, p = 0.05), indicating that the relation between hours a week and cognitive self-regulation was stronger in classrooms with a higher quality of responsive teaching (see Fig. 3). Additionally, a significant interaction was found for the teacher-reported measure of behavioral self-regulation between years in HS and Cognitive Facilitation (β = 0.31, p < 0.05).

Discussion

The present study aimed to address the gap in understanding how preschool dosage for children from low-income families related to kindergarten self-regulation and whether quality moderated the association. Two key findings emerged. First, the number of years, but not hours a week in Head Start related to self-regulation, including cognitive and behavioral self-regulatory skills. Second, the number of hours a week in HS meaningful contributed to self-regulation when classrooms exhibited high levels of responsive teaching or cognitive facilitation, but that was not the case for the number of years in HS. Findings contribute to the growing body of evidence about how dosage and quality of early childhood education experiences relate to children’s development. Results and implications for how we support young children in families experiencing poverty will be further explored below.

Unpacking the Complexity of Dosage and Quality with Children’s Self-Regulation

Findings from this study are consistent with prior research that has found somewhat mixed evidence about how preschool experiences relate to outcomes (see Huston et al., 2015). Specifically, children that attended two years benefited more than those who attended only one year of HS. This result is consistent with studies that found that the number of years in preschool is associated with positive academic (Domitrovich et al., 2013; Xue et al., 2016; Youn, 2016) and behavioral outcomes (Moore et al., 2015; Wen et al., 2012). On the other hand, this study did not find an association between more hours a week and children’s self-regulation in kindergarten. This contrasts with other studies that show more hours a week of attendance in preschool associated with classroom behavior problems (Huston et al., 2015; McCartney et al., 2010; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2004). Thus, the role of dosage continues to be essential but not clear-cut in how it can contribute to children’s development.

This study partially addresses this complexity by examining the moderating role of classroom quality. Specifically, there was a significant positive association between the number of hours a week (and a marginally significant relationship with years) and self-regulation when the quality of the classroom was high. Children who attended HS more hours a week have a positive and stronger association with cognitive and behavioral self-regulation in kindergarten, in classrooms with higher quality teacher–child interactions. More specifically, results revealed a significant interaction between more hours a week and Responsive Teaching, the general factor of classroom quality, for cognitive self-regulation. Children in classrooms with a higher quality of Responsive Teaching benefited more from attending more hours a week than those in low-quality classrooms.

These findings are consistent with previous research examining the relation between the number of hours a week in preschool and child outcomes. McCartney et al. (2010), for example, found that the quality of classroom experiences moderated the adverse effects of more hours of preschool on socioemotional outcomes. In other words, more hours a week in higher-quality classrooms did not relate negatively to socioemotional outcomes, while more hours in low-quality classrooms resulted in negative child outcomes.

Considering Implications for Children in Families Experiencing Poverty

Previous studies have emphasized the importance of quality of preschool experiences for more disadvantaged children, as these children benefit the most from high-quality teacher–child interactions (Hamre & Pianta, 2005). Because the relation between quantity and quality of preschool experiences is largely dependent on the counterfactual experience for a particular child, high-quality interactions in disadvantaged settings are even more critical than in less underprivileged contexts.

Children living in poverty face a particular set of challenges that can harm the development of self-regulation. Children’s development of self-regulation is susceptible to toxic stress exposure, which is characteristic of poverty–living conditions due to economic hardship, food insecurity, unpredictability, and other daily hassles (Blair, 2010; Hamoudi et al., 2015). Research has shown that the relation between stress and attention takes the shape of an inverted U, where some middle-stress levels result in enhanced self-regulation and functioning. In contrast, very low or high-stress levels result in poorer self-regulation (Hamoudi et al., 2015). Chronic or prolonged stimulation of stress results in concentrations of stress hormones in the brain, which inhibit the functioning of higher-order skills.

However, evidence indicates that high-quality preschool experiences can counteract some of the negative effects described above resulting from living in chaotic and stressful household environments (Hamre & Pianta, 2005; Raver et al., 2008). For instance, Hamre and Pianta (2005) conducted a longitudinal study with children identified as at-risk by kindergarten teachers. The authors found that children in classrooms with high emotional and instructional support performed as well as their low-risk peers by the end of first grade on a series of academic and behavioral outcomes. As Obradović (2016) also describes, supportive educational contexts, like those in the classroom with supportive teacher–child interactions, may be conducive for physiologically reactive children.

Limitations

Results need to be considered in light of some limitations, such as the study’s correlational nature and the relative scarcity of information about counterfactual experiences for children who stayed at home. Moreover, the limited external validity of our findings makes this study only applicable to Head Start. Future studies examining preschool experiences should ideally include information about possible counterfactuals to Head Start and other types of early childhood care settings. It is also recommended for future research to test the models presented in this study with a conventional three-factor solution of the CLASS to compare findings.

Despite the limitations, the present study provides new information regarding the relevance of more preschool experiences under the condition that they are high-quality experiences for children from low-income backgrounds. This study can provide a novel contribution to the field as research that examines the dosage of preschool experiences and quality as a moderator using rigorous methods that reduce selection bias is relatively new (Zaslow et al. 2016). As Blair and Raver (2015) have argued, self-regulation may be a primary mechanism through which poverty affects school success; thus, focusing on ways to promote self-regulation in preschool is very important. Therefore, these findings have important policy implications, suggesting the importance of starting Head Start at age three and increasing the number of hours jointly with improving the quality of experiences to support the development of self-regulation. Finally, this research contributes to the current discussion about the role of face-to-face education in early age. Recent evidence has shown an important rate of learning loss (Engzell et al. 2021) and negative consequences on the mental and developmental health of children (de Araújo et al., 2020) due to the school closures because of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Hence, the study of the consequences of preschool dosage and the quality of teachers on self-regulation gives a relevant perspective to continue with the current educational debate.

References

Acar, I. H., Veziroğlu-Çelik, M., Rudasill, K. M., & Sealy, M. A. (2021). Preschool children’s self-regulation and learning behaviors: The moderating role of teacher-child relationship. Child and Youth Care Forum. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-021-09615-3

Ansari, A., & Purtell, K. M. (2018). Absenteeism in head start and children’s academic learning. Child Development, 89(4), 1088–1098. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12800

Araujo, M. C., Carneiro, P., Cruz-Aguayo, Y., & Schady, N. (2014). A helping hand? Teacher quality and learning outcomes in kindergarten. Unpublished manuscript.

Atteberry, A., Bassok, D., & Wong, V. C. (2019). The effects of full-day prekindergarten: Experimental evidence of impacts on children’s school readiness. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 41(4), 537–562. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373719872197

Backer-Grøndahl, A., Nærde, A., & Idsoe, T. (2019). Hot and cool self-regulation, academic competence, and maladjustment: Mediating and differential relations. Child Development, 90(6), 2171–2188. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13104

Berger, A., Kofman, O., Livneh, U., & Henik, A. (2007). Multidisciplinary perspectives on attention and the development of self-regulation. Progress in Neurobiology, 82(5), 256–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.06.004

Berger, A. (2011). Self-regulation: Brain, cognition, and development. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12327-000

Berger, A. (2015). Introduction. In Self-regulation: Brain, cognition, and development (pp. 3–17). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12327-001

Blair, C. (2010). Stress and the development of self-regulation in context. Child Development Perspectives, 4(3), 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2010.00145.x

Blair, C., & Dennis, T. (2015). An optimal balance: The integration of emotion and cognition in context. In Child development at the intersection of emotion and cognition (pp. 17–35). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12059-002

Blair, C., & Raver, C. (2015). School readiness and self-regulation: A developmental psychobiological approach. Annual Review of Psychology, 66(1), 711–731. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015221

Blair, C., & Razza, R. P. (2007). Relating effortful control, executive function, and false belief understanding to emerging math and literacy ability in kindergarten. Child Development, 78(2), 647–663. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01019.x

Burchinal, M., Xue, Y., Auger, A., Tien, H. C., Mashburn, A., Cavadel, E. W., & Peisner-Feinberg, E. (2016). II Quality thresholds, features, and dosage in early care and education: Methods. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 81(2), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/mono.12237

Cadima, J., McWilliam, R. A., & Leal, T. (2010). Environmental risk factors and children’s literacy skills during the transition to elementary school. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 34(1), 24–33.

Calkins, S. D. (1997). Cardiac vagal tone indices of temperamental reactivity and behavioral regulation in young children. Developmental Psychobiology: The Journal of the International Society for Developmental Psychobiology, 31(2), 125–135.

Calkins, S. D., & Williford, A. P. (2009). Taming the terrible twos: Self-regulation and school readiness. In O. A. Barbarin & B. H. Wasik (Eds.), Handbook of child development and early education: Research to practice (pp. 172–198). The Guilford Press.

Coley, R. L., & Lombardi, C. M. (2013). Does maternal employment following childbirth support or inhibit low-income children’s long-term development? Child Development, 84(1), 178–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01840.x

Cook, T. D., Campbell, D. T., & Shadish, W. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Houghton Mifflin.

Curby, T. W., Brock, L., & Hamre, B. (2013). Teachers’ emotional support consistency predicts children’s achievement gains and social skills. Early Education and Development, 24, 292–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2012.665760

de Araújo, L. A., Veloso, C. F., de Campos Souza, M., de Azevedo, J. M. C., & Tarro, G. (2020). The potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on child growth and development: A systematic review. Jornal De Pediatria, 97, 369–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2020.08.008

DeCoster, J. & Lewism M. (2009). Simple Slopes for a 2-way Interaction. https://osf.io/ungcz/

Diamond, A., & Taylor, C. (1996). Development of an aspect of executive control: Development of the abilities to remember what I said and to “do as I say not as I do.” Developmental Psychobiology, 29, 315–334. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2302(199605)29:4%3c315::AID-DEV2%3e3.0.CO;2-T

Domitrovich, C. E., Morgan, N. R., Moore, J. E., Cooper, B. R., Shah, H. K., Jacobson, L., & Greenberg, M. T. (2013). One versus two years: Does length of exposure to an enhanced preschool program impact the academic functioning of disadvantaged children in kindergarten? Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(4), 704–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2013.04.004

Duncan, G. J., Dowsett, C. J., Claessens, A., Magnuson, K., Huston, A. C., Klebanov, P., et al. (2007). School readiness and later achievement. Developmental Psychology, 43(6), 1428. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1428

Edossa, A. K., Schroeders, U., Weinert, S., & Artelt, C. (2018). The development of emotional and behavioral self-regulation and their effects on academic achievement in childhood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 42(2), 192–202.

Ehrlich, S. B., Gwynne, J. A., & Allensworth, E. M. (2018). Pre-kindergarten attendance matters: Early chronic absence patterns and relationships to learning outcomes. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 44, 136–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.02.012

Engzell, P., Frey, A., & Verhagen, M. D. (2021). Learning loss due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. https://doi.org/10.1073/PNAS.2022376118

Entwisle, D. R., Alexander, K. L., Pallas, A. M., & Cadigan, D. (1987). The emergent academic self-image of first graders: Its response to social structure. Child Development, 58, 1190–1206.

Espy, K. A. (2004). Using developmental, cognitive, and neuroscience approaches to understand executive functions in preschool children. Developmental Neuropsychology, 26(1), 379–384. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326942dn2601_1

FACES. (2009). United States Department of Health and Human Services. Administration for Children and Families. Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation. Head Start Family and Child Experiences Survey (FACES): 2009 Cohort [United States]. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2020–03-18. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR34558.v4

Fuller, B., Bein, E., Bridges, M., Kim, Y., & Rabe-Hesketh, S. (2017). Do academic preschools yield stronger benefits? Cognitive emphasis, dosage, and early learning. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 52, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2017.05.001

Halle, T. G., & Darling-Churchill, K. E. (2016). Review of measures of social and emotional development. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 45, 8–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2016.02.003

Hamoudi, A., Murray, D.W., Sorensen, L., & Fontaine, A. (2015). Self-regulation and toxic stress: A review of ecological, biological, and developmental studies of self-regulation and stress.

Hamre, B., Hatfield, B., Pianta, R., & Jamil, F. (2014). Evidence for general and domain-specific elements of teacher-child interactions: Associations with preschool children’s development. Child Development, 85(3), 1257–1274. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12184

Hamre, B., & Pianta, R. C. (2001). Early teacher-child relationships and the trajectory of children’s school outcomes through eighth grade. Child Development, 72(2), 625–638. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00301

Hamre, B., & Pianta, R. C. (2005). Can instructional and emotional support in the first-grade classroom make a difference for children at risk of school failure? Child Development, 76(5), 949–967. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00889.x

Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2007). Learning opportunities in preschool and early elementary classrooms. In R. C. Pianta, M. J. Cox, & K. Snow (Eds.), School readiness and the transition to school (pp. 49–84). Brookes.

Hamre, B. K., Pianta, R. C., Downer, J. T., DeCoster, J., Mashburn, A. J., Jones, S. M., Brown, J. L., Cappella, E., Atkins, M., Rivers, S. E., Brackett, M. A., & Hamagami, A. (2013). Teaching through interactions: Testing a developmental framework of teacher effectiveness in over 4,000 classrooms. The Elementary School Journal, 113(4), 461–487.

Harder, V. S., Stuart, E. A., & Anthony, J. C. (2010). Propensity score techniques and the assessment of measured covariate balance to test causal associations in psychological research. Psychological Methods, 15(3), 234. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019623

Hatfield, B. E., Hestenes, L. L., Kintner-Duffy, V. L., & O’Brien, M. (2012). Classroom Emotional Support predicts differences in preschool children’s cortisol and alpha-amylase levels. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(2), 347–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2012.08.001

Huston, A. C., Bobbitt, K. C., & Bentley, A. (2015). Time spent in child care: How and why does it affect social development? Developmental Psychology, 51(5), 621–634. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038951

Infurna, C. J., & Montes, G. (2020). Two years vs. one: The relationship between dosage of programming and kindergarten readiness. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 13(2), 255–261.

Kane, T. J., McCaffrey, D. F., Miller, T., & Staiger, D. O. (2013). Have we identified effective teachers? Validating measures of effective teaching using random assignment. Research paper. MET Project. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Kuczynski, L., & Kochanska, G. (1995). Function and content of maternal demands: Developmental significance of early demands for competent action. Child Development, 66(3), 616–628. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131938

Lenes, R., McClelland, M. M., ten Braak, D., Idsøe, T., & Størksen, I. (2020). Direct and indirect pathways from children’s early self-regulation to academic achievement in fifth grade in Norway. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 53, 612–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2020.07.005

Leyva, D., Weiland, C., Barata, M., Yoshikawa, H., Snow, C., Treviño, E., & Rolla, A. (2015). Teacher–child interactions in Chile and their associations with prekindergarten outcomes. Child development, 86(3), 781–799.

Loeb, S., Bridges, M., Bassok, D., Fuller, B., & Rumberger, R. W. (2007). How much is too much? The influence of preschool centers on children’s social and cognitive development. Economics of Education Review, 26(1), 52–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2005.11.005

Malanchini, M., Engelhardt, L. E., Grotzinger, A. D., Harden, K. P., & Tucker-Drob, E. M. (2018). “Same but different”: Associations between multiple aspects of self-regulation, cognition, and academic abilities. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 117(6), 1164–1188. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000224

Magnuson, K. A., Ruhm, C., & Waldfogel, J. (2007). Does prekindergarten improve school preparation and performance? Economics of Education Review, 26(1), 33–51.

McCartney, K., Burchinal, M., Clarke-Stewart, A., Bub, K. L., Owen, M. T., Belsky, J., NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. (2010). Testing a series of causal propositions relating time in child care to children’s externalizing behavior. Developmental Psychology, 46(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017886

McClelland, M. M., Cameron, C. E., Connor, C. M., Farris, C. L., Jewkes, A. M., & Morrison, F. J. (2007). Links between behavioral regulation and preschoolers’ literacy, vocabulary, and math skills. Developmental Psychology, 43(4), 947. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.947

Moffitt, T. E., Arseneault, L., Belsky, D., Hancox, R. J., Harrington, H., Houts, R., et al. (2011). A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety, 108(7), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1010076108/-/DCSupplemental/sapp.pdf

Moore, J. E., Cooper, B. R., Domitrovich, C. E., Morgan, N. R., Cleveland, M. J., Shah, H., et al. (2015). The effects of exposure to an enhanced preschool program on the social-emotional functioning of at-risk children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 32, 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2015.03.004

Morris, A. S., John, A., Halliburton, A. L., Morris, M. D. S., Robinson, L. R., Myers, S. S., et al. (2013). Effortful control, behavior problems, and peer relations: What predicts academic adjustment in kindergartners from low-income families? Early Education & Development, 24(6), 813–828. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2013.744682

Murray, D. W., Rosanbalm, K. D., Christopoulos, C., & Hamoudi, A. (2015). Self-regulation and toxic stress: Foundations for understanding self-regulation from an applied developmental perspective (No. OPRE Report 2015–21). Washington DC.

NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. (2004). Trajectories of physical aggression from toddlerhood to middle childhood: Predictors, correlates, and outcome. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 69, 1–143. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452286143.n496

Obradović, J. (2016). Physiological responsivity and executive functioning: Implications for adaptation and resilience in early childhood. Child Development Perspectives, 10(1), 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12164

Peterson, J. L., & Zill, N. (1986). Marital disruption, parent-child relationships, and behavior problems in children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 48, 295–307. https://doi.org/10.2307/352397

Pianta, R. C., la Paro, K. M., & Hamre, B. K. (2008). Classroom Assessment Scoring System: Pre-K Version. Paul H. Brookes.

Ponitz, C. C., McClelland, M. M., Matthews, J. S., & Morrison, F. J. (2009). A structured observation of behavioral self-regulation and its contribution to kindergarten outcomes. Developmental Psychology, 45(3), 605. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015365

Puma, M., Bell, S., Cook, R., Heid, C., Broene, P., Jenkins, F., Mashburn, A., & Downer, J. (2012). Third grade follow-up to the head start impact study: Final report. Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Department of Health and Human Services.

Raver, C., Jones, S. M., Li Grining, C., Zhai, F., Bub, K., & Pressler, E. (2011). CSRP’s impact on low-income preschoolers’ preacademic skills: Self-regulation as a mediating mechanism. Child Development, 82(1), 362–378. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01561.x

Raver, C., Jones, S. M., Li-Grining, C. P., Metzger, M., Champion, K. M., & Sardin, L. (2008). Improving preschool classroom processes: Preliminary findings from a randomized trial implemented in Head Start settings. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23(1), 10–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2007.09.001

Reynolds, A. J., Temple, J. A., White, B. A., Ou, S. R., & Robertson, D. L. (2011). Age 26 cost–benefit analysis of the child-parent center early education program. Child Development, 82(1), 379–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01563.x

Reise, S. P., Moore, T. M., & Haviland, M. G. (2010). Bifactor models and rotations: Exploring the extent to which multidimensional data yield univocal scale scores. Journal of Personality Assessment, 92(6), 544–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2010.496477

Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., Curby, T. W., Grimm, K. J., Nathanson, L., & Brock, L. L. (2009). The contribution of children’s self-regulation and classroom quality to children’s adaptive behaviors in the kindergarten classroom. Developmental Psychology, 45(4), 958–972. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015861

Robson, D. A., Allen, M. S., & Howard, S. J. (2020). Self-regulation in childhood as a predictor of future outcomes: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 146(4), 324–354. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000227

Rosenbaum, P. R., & Rubin, D. B. (1984). Reducing bias in observational studies using subclassification on the propensity score. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 79(387), 516–524. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1984.10478078

Shah, H. K., Domitrovich, C. E., Morgan, N. R., Moore, J. E., Cooper, B. R., Jacobson, L., & Greenberg, M. T. (2017). One or two years of participation: Is dosage of an enhanced publicly funded preschool program associated with the academic and executive function skills of low-income children in early elementary school? Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 40, 123–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2017.03.004

Skibbe, L. E., Connor, C. M., Morrison, F. J., & Jewkes, A. M. (2011). Schooling effects on preschoolers’ self-regulation, early literacy, and language growth. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 26(1), 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2010.05.001

Smith-Donald, R., Raver, C., Hayes, T., & Richardson, B. (2007). Preliminary construct and concurrent validity of the Preschool Self-regulation Assessment (PSRA) for field-based research. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 22(2), 173–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2007.01.002

Stuart, E. A. (2010). Matching methods for causal inference: A review and a look forward. Statistical Science, 25(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1214/09-STS313

Ursache, A., Blair, C., & Raver, C. (2012). The promotion of self-regulation as a means of enhancing school readiness and early achievement in children at risk for school failure. Child Development Perspectives, 6(2), 122–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00209.x

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2002). “Early Childhood Longitudinal Study—Kindergarten Class of 1998–99 (ECLS–K), Psychometric Report for Kindergarten Through First Grade.” NCES 2002–05. National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

Weissberg, R. P., Durlak, J. A., Domitrovich, C. E., & Gullotta, T. P. (2015). Social and emotional learning: Past, present, and future. Handbook of Social and Emotional Learning: Research and Practice. Guilford.

Wen, X., Leow, C., Hahs-Vaughn, D. L., Korfmacher, J., & Marcus, S. M. (2012). Are two years better than one year? A propensity score analysis of the impact of Head Start program duration on children’s school performance in kindergarten. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 27(4), 684–694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2011.07.006

White, I. R., Royston, P., & Wood, A. M. (2011). Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Statistics in Medicine, 30(4), 377–399. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.4067

Xue, Y., Miller, E. B., Auger, A., Pan, Y., Burchinal, M., Tien, H. C., Peisner-Feinberg, E., Zaslow, M., & Tarullo, L. (2016). IV. Testing for dosage-outcome associations in early care and education. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 81(2), 64. https://doi.org/10.1111/mono.12239

Youn, M. (2016). One year or two? The impact of head start enrollment duration on academic achievement. KEDI Journal of Educational Policy, 13(1), 85.

Zaslow, M., Anderson, R., Redd, Z., Wessel, J., Daneri, P., Green, K., Cavadel, E. W., Tarullo, L., Burchinal, M., & Martinez-Beck, I. (2016). I. Quality thresholds, features, and dosage in early care and education: Introduction and literature review. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 81(2), 7–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/mono.12236

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Melo, C., Pianta, R.C., LoCasale-Crouch, J. et al. The Role of Preschool Dosage and Quality in Children’s Self-Regulation Development. Early Childhood Educ J 52, 55–71 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-022-01399-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-022-01399-y