Abstract

The booming live streaming business has increased the number of consumer options for purchase channels, which has had a significant impact on firm sales models and management practices. This paper considers a multiechelon supply chain in which an upstream supplier can sell products through an online platform and a live streaming sales channel, and the online platform can choose to sign a reselling agreement or an agency selling agreement with the supplier. By constructing a Stackelberg game, we theoretically derive the equilibrium strategies of the supply chain members under different selling agreements in the presence of a live streaming sales channel. Specifically, we find that under the reselling agreement, the optimal retail price for the platform decreases with an increase in the commission rate, while the retail price for the live streaming channel always increases with an increase in the commission rate, and the relationship between the wholesale price and the commission rate depends on the ratio of the coefficient on the internet celebrity’s effort for the live streaming channel to that for the online platform. Under the agency selling agreement, there is a threshold in the agency fee. The impact of the commission rate on pricing strategy on one side of the threshold is opposite that on the other side. Furthermore, we numerically explore the impacts of the system parameters on the selection of the sales model, profit, and the decision-making of the supply chain members and identify the conditions under which agency selling and reselling are chosen when there is a live streaming sales channel. Interestingly, we find that the internet celebrity should not charge a commission rate that is too large; otherwise, it harms others without benefiting the celebrity. Moreover, when the supplier chooses to hire an internet celebrity to sell goods via live streaming, the supplier should choose a celebrity with either an extremely large following or with little influence but should not choose a celebrity with only moderate influence.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

With the rapid development of the internet marketplace, shopping on online platforms has become increasingly popular in people’s daily lives [6, 21]. According to eMarketer, a global market research company, global e-commerce sales were expected to exceed US $4 trillion by 2020, US $5 trillion by 2022, and US $6 trillion or more by 2024. By relying on the respective advantages of online platforms and suppliers, online sales make full use of their synergy [23, 40]. As online platforms and suppliers have joined the online sales market, supply chain competition has become increasingly fierce. In traditional offline retail sales, retailers usually initiate orders, and then suppliers sell the products to retailers at wholesale prices. Retailers then sell the products to consumers at retail prices. In e-commerce, many online platforms, such as Amazon and JD.com, have emerged. Early on, these online platforms generally adopted reselling models. In such models, the platform acts as a retailer: it purchases products from upstream suppliers at wholesale prices and then sells them on its platform at retail prices. This model is similar to the traditional offline model of retail sales. In recent years, a growing number of online platforms have moved away from acting as a single reseller and have started to implement the agency selling model as well [1, 45]. In fact, Taobao.com may be the first online platform to use agency selling in China. In agency selling, suppliers sell goods directly to consumers on the platform, but the suppliers need to pay a certain fee to the platform. For both the online platforms and suppliers, there are significant differences in the operational decisions made and profits earned under the different sales models.

With the diversification of sales channels, consumers’ purchasing experiences are very important for their choice regarding the channel through which they make purchases. Hence, some suppliers who originally only sold products through online channels have expanded into physical retail stores to provide customers with a seamless shopping experience through all available shopping channels. A typical example is Xiaomi, a Chinese smartphone manufacturer that previously sold products through JD.com, a large online retail platform. Now, it has opened offline retail stores and sells products directly to consumers offline [8, 44]. Although it is convenient for consumers to buy goods online, they cannot experience or carefully observe the products, which increases the possibility that consumers will make a mistake in choosing a product. As a result, many online platforms have incorporated live streaming into their business marketing. Especially since 2019, with the outbreak of COVID-19, the development of the live streaming business has been particularly fast and popular. Selling goods via live streaming has become the main approach to marketing for many large e-commerce platforms. Live streaming marketing is a marketing activity in which a live broadcast is the carrier of the message and the live video content provides the marketing theme. Live marketing is flexible and intuitive, and it provides consumers with a different experience from that of their previous online shopping. As a new marketing method, live streaming marketing has injected fresh blood into the development of e-commerce. What are the advantages of live streaming marketing?

First, live streaming marketing can effectively reduce marketing costs for enterprises. The most important principle in the development of an enterprise is to obtain the maximum economic benefit possible and provide the best service at the lowest cost. Traditional marketing models have substantial time and money costs, while the use of live marketing can generate more profitable models, and the content and form of promotions are not limited. In addition, live streaming can better exhibit the performance of products and the company’s culture, and it can deliver a large amount of content that cannot be conveyed through advertising. The information displayed in a live broadcast is real and timely, which makes it easy to win the trust of customers. Specifically, the products that consumers see in the live broadcast room are what they receive, which cannot be counterfeited, in order to give consumers a stronger sensory experience and to improve sales conversion rates. The last and most important point is that (internet) celebrities selling through live channels have more fans, or larger “followings”. An internet celebrity can attract more consumers to buy a product through her fan group than can traditional advertising, which improves corporate profits.

Many previous studies on the selection of a selling strategy by members of a supply chain have generally focused on reselling, agency selling, or a hybrid selling model. However, there is no research that has considered the selection of the selling model in the context of live streaming commerce. Based on this, the key issues considered in this paper include the following:

-

In the context of live streaming selling, what are the different equilibrium decisions of the supply chain members under an agency selling agreement and a reselling agreement?

-

How do system parameters, such as the agency fee and the self-effort coefficient, affect the supply chain members’ decisions and profits?

-

If a supplier chooses a celebrity to sell his goods via live streaming, what level of celebrity should he choose to maximize his profit?

To answer the above key questions, we build a stylized game-theoretical model in which an upstream supplier can sell its products through an online platform and an internet celebrity live streaming channel. Note that we assume that the supplier pays a commission to the celebrity in two ways: one is that the celebrity receives a certain commission for each unit of product that she sells, which we call a commission rate payment; the other is that regardless of how many products the celebrity sells, the supplier pays her a fixed commission, which we call a fixed commission payment. Given that the platform has strong market power, it has the option of entering into a reselling agreement or an agency selling agreement with the supplier. In the former agreement, the platform acts as a retailer that buys products from the upstream supplier at a unit wholesale price and then sells those products to consumers in the marketplace at a unit retail price. In the latter agreement, the platform allows the supplier to sell its products directly to consumers, but the supplier needs to pay a fraction of its profits to the platform as an agency fee. One of our innovations is that we consider the impact of the characteristics of the live streaming sales channel on the decision-making and profits of the supply chain members. To analyze such supply chain systems, we first consider the profit maximization of the entire supply chain, analyzing the supply chain members’ optimal decisions in a centralized supply chain. Then, given that the supply chain members aim to maximize their own profits, we obtain the theoretical equilibrium solutions for the supply chain members under both a reselling agreement and an agency selling agreement and further analyze some of the structural properties of the equilibrium solution. Finally, we numerically investigate the impact of the system parameters on the supply chain members’ decisions and profits.

Our study obtains several interesting findings. First, total profits in the centralized supply chain are identical under agency selling and reselling because the profits and costs are only transferred among the supply chain members. In the decentralized supply chain, the optimal effort level of the internet celebrity in the live streaming channel increases as the commission rate increases and decreases as the effort cost coefficient increases in the case of a commission rate payment. However, the optimal effort level of the internet celebrity in the case of a fixed commission is always 0. Additionally, there are thresholds in the agency fee, and the supply chain members have opposite preferences over the selling models on either side of these thresholds. Moreover, the monotonicity of the supplier’s prices with respect to the commission rate depends on the choice of the platform sales model or the ratio of the self-effort coefficient to the cross-effort coefficient in the reselling mode; and the agency fee in the agency selling mode.

Second, in addition to the agency fee and the ratio of the self-effort coefficient to the cross-effort coefficient, the commission rate and fixed commission in the live streaming commerce model significantly affect the equilibrium strategies within the system. Specifically, the platform’s profits increase as the commission rate increases, while the supplier’s profits decrease as the commission rate increases. Interestingly, the celebrity’s profits first increase and then decrease as the commission rate increases. This result guides the celebrity to not choose a particularly high commission rate; otherwise, the gains may not outweigh the losses. In addition, compared to the commission rate case, the supplier prefers the fixed commission when the fixed commission is relatively low and the commission rate when the fixed commission is relatively high. However, the preferences of the internet celebrity over the commission payment methods are opposite those of the supplier.

Third, we find that the platform’s profit increases as the internet celebrity’s influence increases, and the celebrity’s profit decreases as the celebrity’s influence increases when the supplier and the internet celebrity reach a commission rate agreement. Interestingly, the supplier’s profit first decreases and then increases as the celebrity’s influence increases. In other words, when the supplier, as the leader of the supply chain system, chooses to have the internet celebrity sell goods via live streaming, he should not choose a celebrity with moderate influence but rather a celebrity with either an extremely large following or little influence. The intuition behind this result is that when the celebrity has an extremely large following, even if she does not put forth much effort to sell the products, her strong fan base will generate more demand over the live streaming channel, and when the celebrity has a smaller following, she will put forth more effort to attract her fans to buy the product. Only those celebrities whose influence tends to be moderate will not have enough fans and will not put forth sufficient effort to sell goods via live streaming. As a result, the sales volume of the live broadcast channel will be low, thus reducing the profits of the supplier.

The contributions of our research are mainly embodied in three aspects. First, although the research on the selection of selling contracts between suppliers and platforms is very rich, the impact of live broadcasting on the selection of selling contracts of supply chain members has not been analyzed. Our work attempts to fill this gap. Second, our work studies the interaction among live streaming, platform sales models, and pricing strategy, which produced new and counter-intuitive results. Third, our research points out the conditions for the supplier to choose to hire an internet celebrity to sell goods through live streaming. This finding has important practical implications for the supplier’s live broadcast marketing strategy.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature related to our paper and identifies the gaps in the existing literature. Section 3 describes the problem and constructs the multistage game models under the reselling and agency selling agreements. We derive the equilibrium strategies under the reselling and agency selling agreements and present them in Sects. 4 and 5, respectively. In Sect. 6, we numerically investigate the impacts of some system parameters on the supply chain members’ profits and decisions. Section 7 concludes the paper and discusses the managerial implications.

2 Related literature

This paper studies the impact of live streaming commerce on supply chain members’ decisions under reselling and agency selling agreements. There are two streams of literature closely related to our research, which are discussed below.

2.1 Live streaming commerce

Live streaming marketing is a brand-new marketing model that was introduced in 2016 and has developed rapidly since 2019. Especially after the outbreak of COVID-19, live streaming marketing has been attracting increasing attention.svart [37] showed that live streaming is still a new way for businesses to market their products, and many companies have not started using live streaming marketing. There is clear evidence that live streaming is gaining ground as a share of enterprise marketing activities. However, there is still relatively little research on the marketing model of live streaming commerce. At present, the research on live streaming marketing focuses mainly on empirical analysis and theoretical modeling. In the empirical literature,Wongkitrungrueng and Assarut [38] proposed a comprehensive framework with which to examine the relationships among customers’ perceived value of live streaming, trust, and engagement.Wongkitrungrueng et al. [39] analyzed Facebook data on live streaming sellers to assess the nature and extent of engagement by using a mixed quantitative and qualitative approach.Chen et al. [2] investigated the impact of interpersonal interactions between buyers and sellers on the purchase intention of buyers, incorporating “swift guanxi" as a mediator.Lu and Chen [29] studied the influence of live streaming on consumers’ purchase intentions in online markets for clothes and cosmetics from the perspectives of signaling theory and uncertainty. Gao et al. [10] studied a link between live streamer trustworthiness and message persuasiveness and provided managerial implications for live streaming commerce practitioners. Zhang et al. [25] empirically examined the impact of live streaming on customers’ online purchase intentions in light of psychological distance and perceived uncertainty using construal level theory. Li et al. [25] investigated how viewers’ salient and coexisting identities (i.e., class and relational identities) affect their gifting choices based on the identity-based motivation model.Kang et al. [17] explored the dynamic effect of interactivity on customer engagement behavior through data from live streaming commerce platforms and found that interactivity has a nonlinear (inverted U-shaped) relationship with customer engagement and that the strength of relationships is a complete mediator between interactivity and customer engagement. Sun et al. [36] constructed a theoretical model that accounts for the affordability of IT to study how live streaming affects social commerce customers’ purchase intentions in China and empirically estimated the model by surveying customers who had shopped via live streaming shopping platforms, including Taobao.com, JD.com, Mogujie.com, and Sina Microblog. Some studies, for example, Lin et al. [26] and Lu et al. [30], have used field data to explore the drivers of tipping during live streaming; the difference between these studies is that Lu et al. [30] focused on audience size, while Lin et al. [26] focused on the interactions between the viewers’ and broadcasters’ emotions. Geng et al. [11] investigated whether and how internet celebrities acting as content marketers and fans acting as seed consumers affect the sales performance of e-commerce businesses. Clement Addo et al. [7] investigated the impact of customer engagement during digital marketing live streaming on purchase intentions and showed that customer engagement is significantly associated with followership and purchase intentions during digital marketing live streaming. Although price is a significant moderator, the impact of price on purchase intentions becomes insignificant once consumers become followers. Hu and Chaudhry [14] explored whether and how relational bonds enhance consumers’ engagement with e-commerce live streaming and examined the relationships among relational bonds, affective commitment, and consumer engagement. In the modeling literature, Zhu and Liu [46] discussed four models for live streaming e-commerce logistics service supply chains (LSE-LSSC), compared the optimal product prices, logistics service levels, and profits of the related players, and further investigated the impacts of a cost-sharing mechanism on the LSE-LSSC. Lv et al. [31] presented a live streaming information dissemination game model to simulate multiple complex live streaming e-commerce networks and pointed out that the broadcasters or merchants in live streaming e-commerce can implement reasonable incentive strategies to promote information dissemination in different reputation environments through social networks. Mao et al. [32] studied the pricing strategy of new products when they are launched in live streaming considering consumer uncertainty and network externality, and found that whether to adopt penetration pricing strategy or skimming pricing strategy for new products depends on the impact of live streaming, consumer uncertainty, and network externality. Li et al. [20] developed a stylized model to investigate when introducing an influencer marketing channel can improve the profitability of a retailer and social welfare, with and without a merchant’s live streaming channel.

2.2 Agency selling and reselling

For enterprises, the choice of sales model is very important for their growth. Especially in the context of e-commerce, online platforms such as Amazon and JD.com utilize multiple sales models, among which reselling and agency selling are two of the most common. Recently, some studies have studied these two sales models simultaneously. One comprehensive and insightful study is Abhishek et al. [1]. By comparing different e-channel structures, the authors identify the conditions under which agency selling should be used. Specifically, e-tailers should use agency selling when spillovers from the electronic channel to the traditional channel are negative, absent, or positive but small. When market competition intensifies, e-retailers also have a stronger motivation to use agency selling. Kwark et al. [18] examined the effect of third-party information (e.g., online product reviews) in a model of channel structure that included a retailer carrying two substitutable products. The retailer may use a wholesale scheme or a platform (agency) scheme. The results suggested that the effects of the same third-party information on the retailer can be in opposite directions depending on the pricing scheme used. Li et al. [24] pointed out that although the hybrid model is an inevitable trend that helps alleviate the burden of product expansion under reselling, reselling may also be subject to sales cannibalization from agency selling. Based on this phenomenon, they studied the impact of agency selling on reselling.Zhang and Zhang [44] studied agency selling and reselling agreements between suppliers and e-tailers and provided the conditions under which e-retailers should share or withhold information on demand under these two agreements. Pu et al. [33] investigated three possible online sales strategies (including direct selling, reselling, and agency selling) for a manufacturer that also distributes its products through an independent retailer using traditional channels and derived the conditions under which each strategy is optimal. Ha et al. [12] further derived conditions under which each of the three channel structures (agency channel, reselling channel, and dual-channel) emerges in equilibrium. Liu et al. [28] investigated a platform’s preferences over reselling and agency selling considering the impact of data-driven marketing and found that platforms are more inclined to adopt a reselling model as data-driven marketing improves. Zennyo [43] studied the strategic contract between a monopoly platform and two competing suppliers who sell goods through the platform. Each supplier can choose one of two contracts: wholesale or agency. The results suggested that asymmetric contract selection may occur in equilibrium. Liu et al. [27] also studied the contract selection of resale and agency sales, and a significant difference is that they considered two competing downstream online retail platforms. Pu et al. [34] discussed the marketing and pricing strategies of manufacturers under different offline channel power structures and sales modes, and indicated that online agency selling mode is the best option for manufacturer when the commission rate is less than a threshold. Fu et al. [9] considered a supplier that distributes its products through a brick-and-mortar retailer and an e-tailer that has the flexibility to use both reselling or a combined reselling and agency selling model. The results showed that the addition of agency selling is not always beneficial to the supplier nor to the brick-and-mortar retailer relative to the outcomes of the reselling model. Xu et al. [41] and Xu and Choi [42] studied supply chain operations with online platforms under the cap-and-trade regulation. In their papers, the online platform can operate under either the agency mode or reselling mode. Differently, Xu et al. [41] considered the impact of demand disruption but Xu and Choi [42] explored the impact of using blockchain technology. Chen et al. [4] further took information sharing into account and studied the influence of reselling contracts and agency selling contracts on platform information sharing incentives when the platform recommends or does not recommend a product. Chen et al. [5] investigated an e-seller’s strategy of offering return-freight insurance in the reselling and agency selling formats, and found the conditions of offering return-freight insurance in the agency selling format are more stringent than in the reselling format. Sun and Ji [35] studied an e-commerce setting in which an online platform provides IoT infrastructure and a manufacturer sells its products on the platform. They examined the interactions among the manufacturer’s IoT investment decision, the platform’s pricing model choice, and the platform’s transfer payment strategy. Ji et al. [16] studied how social communications affect upstream product line design when the intermediate platform makes strategic contract choices. They showed that an agency contract can be preferred in the presence of social communications over a wholesale contract when the commission rate is sufficiently high or both the commission rate and the product line extension fee are moderate. Chen [3] investigated a manufacturer’s online selling strategy choice between wholesale selling and agency selling, and discussed the impact of the spillover effect from online sales to offline sales.

In summarizing the above literature, we find that there are many studies on live streaming marketing, but most of these studies are based on empirical analysis, while the relevant theoretical modeling literature on live streaming marketing is extremely sparse. In addition, although there are some relevant studies on reselling and agency selling, there is no research that considers the choice between agency selling and reselling in a live streaming commerce environment. Given this state of the literature, our paper constructs a stylized game model, theoretically analyzes the decisions of supply chain members under both reselling and agency agreements when live streaming sales channels are available and further analyzes the influence of the system parameters on the performance of the supply chain members through numerical analysis.

3 Model preliminaries

E-commerce has promoted the rapid development of live broadcast marketing and platform economy. There have been many studies on the platform sales mode in the supply chain, but there are few studies simultaneously considering the selection of live broadcast and platform sales mode. Our work aims to consider the interaction between live streaming and platform sales model selection.

3.1 Problem description

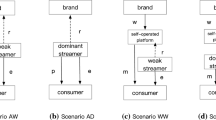

We consider a supplier who can sell his products both through an online platform and through an internet celebrity live streaming channelFootnote 1. As the online platform has strong market power, it has the option of entering into a reselling agreement or an agency selling agreement with the upstream supplier. In the former agreement, the platform acts as a retailer who buys products from the upstream supplier at unit wholesale price w and sells those products to consumers in the marketplace at unit retail price \(p_1\). In the latter agreement, the platform allows the supplier to sell his products to the consumers directly, but the supplier must pay a fraction \(\alpha \ (0\le \alpha \le 1)\) of his profits as an agency fee to the platform. There are many real-world examples of this supply chain structure. JD.com, for example, not only serves as a thirty-party sales platform but also acts as an intermediary retailer. In addition, with the continual development of the internet, online platforms and live streaming e-commerce are developing rapidly, especially under the influence of the measures to address COVID-19, and live streaming sales have become even more popular. An increasing number of internet celebrities have begun to choose e-commerce platforms to work with or to cooperate with upstream suppliers and have begun to sell goods via live streaming. To explore the impacts of live streaming marketing on the choice of sales agreement between the online platform and the upstream supplier and the optimal strategies for the supply chain members, in this paper, we assume that the supplier can also sell his products at a retail price \(p_2\) through the live streaming channel in addition to the online platform, but he needs to pay a certain commission to the internet celebrity. We assume that there are two ways for suppliers to pay this commission to the internet celebrity: one is to pay a commission of s to the internet celebrity for every unit of product sold; the other is to pay the internet celebrity a fixed commission F regardless of how many products she sells. Without loss of generality, we assume that the production cost for the product is 0. For convenience, we explicitly show the supply chain structure under the different sales models and when conducting business via live streaming in Fig. 1.

3.2 Demand formulations

The external demand in this study comes from the online platform sales channel and the live streaming sales channel. We denote the demand that comes from the online platform as \(D_1\) and the demand that comes from the live streaming channel as \(D_2\). Consistent with previous studies, the demand from the two channels is affected by the price in the corresponding channel (i.e., its own price) and the price of the other channel (i.e., the cross-price). As mentioned above, we assume that the platform has strong market power, so it can choose to sign a reselling agreement or an agency selling agreement with the supplier. Unlike previous studies, we have also taken into account the impact of live streaming marketing. In the live streaming channel, internet celebrities need to exert effort to attract more consumers to buy products. We denote the sales effort of the internet celebrity as e. Clearly, the higher the effort exerted by the internet celebrity is, the more products that will be sold through the live streaming channel and the fewer the sales on the platform channel will be. Following Hua et al. [15], Li et al. [19], and He et al. [13], we assume that demand is linear in its own price, the cross-price, and the effort level of the internet celebrities. Suppose the overall demand in the market is a, it comes from the online platform and the live streaming channel. We define \(\theta\) and \(1-\theta\) as the proportions of the overall demand coming from the online platform and from the live streaming channel, respectively. Then, the demand functions can be formulated as follows:

where \(a_1=\theta a\) and \(a_2=(1-\theta ) a\) are the potential market sizes of the online retailing channel and the live streaming channel, \(b_1\) and \(b_2\) are the own-price coefficients for \(D_1\) and \(D_2\), and \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) are the cross-price coefficients for \(D_1\) and \(D_2\). To increase tractability, we assume that \(c_1=c_2=c\). Obviously, \(b_1>c>0,\ \beta _1>\beta _2>0\), and \(b_2>c>0\).

Before proceeding, we give the relevant constraints on the prices \(w,\ p_1\), and \(\ p_2\). We do not consider product returns, so the demand for the two channels is not negative. From \(D_1\ge 0, D_2\ge 0\), we have

For conciseness, we denote \(A_1=\frac{a_1b_2+a_2 c}{b_1b_2-c^2},\ B_1=\frac{\beta _1c-\beta _2b_2}{b_1b_2-c^2},\ A_2=\frac{a_1c+a_2b_1}{b_1b_2-c^2},\ B_2=\frac{\beta _1b_1-\beta _2c}{b_1b_2-c^2}\).

3.3 Profit functions

Before presenting the supply chain members’ profit functions, we first characterize the two fee payment structures for the internet celebrity: a commission rate (C) and a fixed commission (F). According to the descriptions given above, the fee \(C^j\) paid to the internet celebrity under each structure can be formulated as follows:

We denote the profit of the supplier as \(\Pi _s^i\), and this profit is earned through both the online platform and the live streaming channel. Since the profit of the supplier consists of the total sales from the two channels minus the fees paid to the internet celebrity, we have

Note that \(i\in \{R, A\}\). When \(i=R\), a reselling agreement is reached between the online platform and the supplier, and when \(i=A\), an agency selling agreement is reached between the online platform and the supplier.

Correspondingly, the profit function of the online platform is

In the live streaming channel, demand is closely related to the effort exerted by the internet celebrity. Suppose that the cost of effort is C(e). Clearly, the higher the effort level, the greater the demand from the live streaming channel, but at the same time, the higher the cost to the internet celebrity. That is, \(\frac{dC(e)}{de}>0\). Besides, the higher the effort level, the higher the marginal cost of increasing the effort level. That is, \(\frac{d^2C(e)}{de^2}>0\). It is worth noting that the quadratic effort cost function satisfies these conditions and has been widely used in previous studies. Following Li et al. [22], Li et al. [19], and Sun and Ji [35], we assume that \(C(e)=\frac{1}{2}ke^2\). Then, the profit function of the internet celebrity can be formulated as follows:

Note that k is sufficiently large. If the coefficient on the cost of effort k is too small, then the effort level e will be too high, which leads to excessive demand from the live streaming channel, while the demand from the online platform tends toward 0. This outcome is unrealistic for our research setting.

For easy reference, we list all notation in Table 1.

3.4 Sequence of events

As the platform has more power, the blueplatform first chooses whether to sign a reselling or an agency selling agreement with the upstream supplier in Stage 1. If the platform chooses a reselling agreement, the supplier sets his wholesale price w for the online platform and a retail price \(p_2\) for the live streaming channel in Stage 2. Then, in Stage 3, the platform decides on its retail price \(p_1\) for the consumers who buy its products. Finally, the internet celebrity decides on her effort level e in Stage 4. If the platform chooses the agency selling agreement, the supplier decides on his retail prices \(p_1\) and \(p_2\) for the online platform channel and the live streaming channel, respectively, in Stage 2. Then, the internet celebrity decides on her effort level e in Stage 3. Figure 2 shows this sequence of events in detail.

4 Analysis and results in the commission rate case

In this section, we consider the commission rate case in which the supplier pays a commission s to the internet celebrity for each unit of product sold through the live streaming channel. Before analyzing this case in the context of a decentralized supply chain, we first analyze it in the context of a centralized supply chain.

4.1 Centralized supply chain

In a centralized supply chain, the supplier, the platform, and the internet celebrity are vertically integrated and make decisions to maximize the overall profit of the supply chain. Note that the total cost under the centralized supply chain remains unchanged regardless of the sales agreements and the commission payment methods. That is, even under different payment methods and sales agreements, the pricing and effort level decisions in the centralized supply chain are always the same. For conciseness, we omit the scripts on the parameters and variables when defining the centralized supply chain. Thus, total profits in the centralized supply chain are

The supply chain members decide on retail prices \(p_1\) and \(p_2\) as well as effort level e. To obtain the optimal decisions, we use a two-stage optimization method for this centralized supply chain. Before computing the optimal equilibrium, we first check the concavity of the total cost with respect to its elements and obtain the following lemma:

Lemma 1

The total profit of the centralized supply chain \(\Pi _c\) is jointly concave in \(p_1\) and \(p_2\) but not jointly concave in \(p_1\), \(p_2\), and e.

The proof of Lemma 1, as well as all other lemmas and propositions, are presented in the Appendix. Lemma 1 shows that for any given effort level e, there exists a unique equilibrium solution that corresponds to the optimal pricing decision, which maximizes the total profit of the centralized supply chain. The following lemma describes the specific pricing decisions.

Lemma 2

For any given effort level e, the optimal pricing policy for the supplier is

and the optimal total profit in the centralized supply chain is

From Lemma 2, we can derive the structural properties of the optimal pricing strategy as follows:

Proposition 1

The impacts of the effort level e on the pricing strategies are as follows:

-

(i)

if \(\frac{\beta _1}{\beta _2}>\frac{b_2}{c}\), \(p_1^{c,*}(e)\) and \(p_2^{c,*}(e)\) are increasing in e;

-

(ii)

if \(1<\frac{\beta _1}{\beta _2}<\frac{b_2}{c}\), \(p_2^{c,*}(e)\) is increasing in e while \(p_1^{c,*}(e)\) is decreasing in e.

Proposition 1 shows that the optimal pricing strategy is closely related to the ratio of the self- coeffcient to the cross-coeffcient of effort level. Specifically, when the ratio of these coefficients is relatively large, the retail price \(p_1^{c,*}\) (which is decided by the supplier under the agency selling agreement but decided by the online platform under the reselling agreement) and the retail price for the live streaming channel \(p_2^{c,*}\) increase with an increase in effort level e. When the ratio of the coefficient on effort for the live streaming channel to the coefficient for the platform is relatively large, the retail price of live streaming channel \(p_2^{c,*}\) increases with an increase in effort level e, but the retail price \(p_1^{c,*}\) decreases with an increase in effort level e. The reason is that when the ratio of the coefficients on effort is relatively large, an increase in effort on the live streaming channel can bring about a large increase in the net demand from the two channels. Thus, the supplier or the platform can sell a large number of products even if they raise prices, whereas when the ratio is relatively small, the increment in net demand due to an increase in effort on the live streaming will be relatively small. In other words, due to the increase in effort level, the demand from the live streaming sales channel increases, while the demand associated with the platform decreases substantially. Therefore, the optimal price for the live streaming channel \(p_2^{c,*}\) increases, which can also create greater demand, while the platform should reduce its price to attract more consumers to offset the reduction in demand caused by the effort of the internet celebrity.

Following Lemma 2, we obtain the optimal pricing decisions for any given effort level e. However, we cannot see directly that the function \(\Pi ^*(e)\) is concave in e. Recall that the effort cost coefficient k is assumed to be sufficiently large; thus, the effort level e will not be too high. We assume that \(e\in [0,\bar{e}]\). Then, for a continuous function \(\Pi ^*(e)\), there must be a maximum value within this closed interval. After obtaining the optimal effort level \(e^*\), we substitute Eq. (8) into Eq. (9), and we can thus obtain the optimal pricing strategy.

4.2 Decentralized supply chain

In practice, supply chain members generally aim to maximize their own profits and tend to ignore the overall profits of the supply chain. This section considers a decentralized supply chain with an upstream supplier, an online platform, and a live streaming channel, which together constitute a Stackelberg game in which the supplier is the leader and the online platform and internet celebrity from the live streaming channel are the followers. In this decentralized supply chain, the supply chain members make their own decisions sequentially in order to maximize their individual profits. Next, we analyze the equilibrium results for the decentralized supply chain under a reselling agreement and an agency selling agreement between the platform and the supplier.

4.2.1 Equilibrium results under reselling agreement

Under the reselling agreement, the supplier, as the leader, first decides his wholesale price w and retail price \(p_2\) for the online platform and the live streaming channel, respectively. Then, the platform acts as a retailer and decides retail price \(p_1\) for the external consumers. Finally, the internet celebrity from the live streaming channel chooses her effort level e, which significantly affects the consumer demand in the market. In this decentralized setting, all supply chain members make decisions with the objective of maximizing their own profits. The decision-making process for this supply chain system is a three-stage game, and we use backward induction to solve it.

4.2.1.1 The internet celebrity’s problem

The internet celebrity from the live streaming channel uses her influence and popularity to help the upstream supplier market products to consumers. After the supplier sells his products through the live streaming channel, he needs to pay a commission to the celebrity. In this section, we assume that the commission rate paid by the supplier to the celebrity for each unit of product sold is s. To obtain a higher commission, the celebrity generally publishes advertisements online or uses other means to attract consumers to watch her sell goods on the live streaming platform, which leads to the payment of corresponding costs. Obviously, the higher the effort level of the celebrity is, the greater the cost she incurs. The specific cost structure is described in detail above.

Using backward induction, for any given \(w,\ p_1,\) and \(\ p_2\), we first check the concavity of the profit function \(\Pi _l^{cr}=s D_2-\frac{1}{2}ke^2\) with respect to effort level e. Clearly, \(\Pi _l^{cr}\) is concave in e. We thus obtain the optimal effort level, which is presented in the following lemma.

Lemma 3

Given \(w, p_1\) and \(p_2\), the internet celebrity’s optimal effort level is \(e^{cr,*}=\frac{\beta _1 s}{k}\).

From Lemma 3, we find that the optimal effort level \(e^{cr,*}\) is independent of \(p_1\), \(p_2\) and w, which is a constant dependent on the parameters \(\beta _1\), s, and k. Lemma 3 shows that the greater the coefficient on the effort level k is, the lower the optimal effort level \(e^*\), which is consistent with our assumptions. In addition, the higher the commission rate s is and the coefficient on effort for the live streaming channel \(\beta _1\) is, the higher the optimal effort level \(e^*\) because the higher commission rate encourages the celebrity to exert more effort to sell more goods, which is consistent with reality. In fact, the effort made by the internet celebrity is based on the maximization of her own profit, and she only needs to find a balance between the commission she receives and the cost she pays.

4.2.1.2 The online platform’s problem

Under a reselling agreement, the online platform acts as a retailer, purchasing products from the upstream supplier and selling products to the downstream consumers. For any given wholesale price w and retail price for the live streaming channel \(p_2\), we substitute the optimal effort level \(e^{cr,*}\) into Eq. (5) and obtain the profit function for the online platform:

Obviously, for any given w and \(p_2\), \(\Pi _p^{cr}(w,p_2)\) is concave in \(p_1\). Thus, there exists a unique equilibrium solution corresponding to the optimal retail price of the platform.

Lemma 4

Given the supplier’s prices w and \(p_2\), the platform’s optimal price is

Proposition 2

The platform’s optimal price \(p_1^{cr,*}\) is increasing in the wholesale price w and the retail price for the live streaming channel \(p_2\) but decreasing in the commission rate s.

The reason for the result in Proposition 2 is that when the supplier’s wholesale price for the platform increases, the platform raises its retail price to obtain higher profits. In addition, an increase in the supplier’s retail price for the live streaming channel reduces the demand associated with the live streaming channel and increases the demand associated with the platform. To equilibrate supply and demand, the platform chooses to increase its retail price.

4.2.1.3 The supplier’s problem

In the reselling agreement, the supplier, as the Stackelberg leader, needs to simultaneously choose the wholesale price w for the online platform and the retail price \(p_2\) for the live streaming channel. If we substitute \(e^{cr,*}\) and \(p_1^{cr,*}(w,p_2)\) into Eq. (4), we can obtain the supplier’s profit as follows:

Before computing the optimal prices \(w^{cr,*}\) and \(p_2^{cr,*}\), we first analyze the concavity of \(\Pi _s^{cr}(w,p_2)\) with respect to w and \(p_2\) and find that \(\Pi _s^{cr}(w,p_2)\) is jointly concave in w and \(p_2\). Thus, there exists a unique solution corresponding to the equilibrium pricing strategy.

Lemma 5

\(\Pi _s^{cr}(w, p_2)\) is jointly concave in w and \(p_2\), and the supplier’s optimal prices are

Substituting Eq. (14) and Eq. (15) into Eq. (13), we obtain the supplier’s optimal profits.

After obtaining the optimal pricing strategy \(p_2^{cr,*}\) and \(w^{cr,*}\), we substitute the optimal prices into Eq. (12), giving us the optimal pricing strategy for the online platform, \(p_1^{cr,*}(w^{cr,*},p_2^{cr,*})\).

Proposition 3

The impact of the commission rate s on the pricing strategies under the reselling agreement is as follows:

-

(i)

\(p_2^{cr,*}\) is always increasing in s;

-

(ii)

if \(\frac{\beta _1}{\beta _2}>\frac{b_2}{c}\), then \(w^{cr,*}\) is increasing in s, but if \(1<\frac{\beta _1}{\beta _2}<\frac{b_2}{c}\), then \(w^{cr,*}\) is decreasing in s.

Proposition 3 shows that the monotonicity of the supplier’s optimal price \(w^{cr,*}\) with respect to the commission rate s is closely related to the ratio of the coefficient on the internet celebrity’s effort level for the live streaming channel to that for the platform. The reason for this result is similar to that for Proposition 1, so we omit the details here. In addition, the optimal price for the live streaming channel \(p_2^{cr,*}\) is always increasing in the commission rate s. The reason for this result is that when the commission rate paid by the supplier to the internet celebrity increases, the supplier increases his price for the live streaming channel to offset the fees paid to the celebrity. In other words, the cost of hiring the internet celebrity is passed on to the consumers.

4.2.2 Equilibrium results under the agency selling agreement

In this section, we consider the case in which the online platform signs an agency selling agreement with the upstream supplier. Under this agreement, the supplier sells products directly to downstream consumers via the online platform by paying a certain proportion of his profits to the online platform.

4.2.2.1 The internet celebrity’s problem

Clearly, the optimal effort level of the internet celebrity under the agency selling agreement is the same as that under the reselling agreement, i.e., \(e^{ca,*}=\frac{\beta _1 s}{k}\).

4.2.2.2 The supplier’s problem

Under the agency selling agreement, the supplier does not need to decide on a wholesale price. Instead, he needs to simultaneously decide on a retail price \(p_1\) for the online platform and a retail price \(p_2\) for the live streaming channel. We substitute the optimal effort level \(e^{ca,*}\) into Eq. (4), and the supplier’s profit function is obtained as follows:

By computing the second-order Hessian matrix for \(\Pi _s^{ca}\), it is easy to verify that \(\Pi _s^{ca}\) is not necessarily jointly concave with respect to \(p_1\) and \(p_2\) when the parameters are unconstrained. For tractability, we assume that \(4(1-\alpha ) b_1 b_2 -((2 - \alpha )^2 c^2>0\). Such a constraint is easily satisfied because in practice, the agency fee \(\alpha\) is generally not very high, and the own-price coefficients \(b_1\) and \(b_2\) are significantly greater than the cross-price coefficients.

Lemma 6

\(\Pi _s^{ca}(p_1,p_2)\) is jointly concave in \(p_1\) and \(p_2\), and the optimal retail prices for the online platform, \(p_1^{ca,*}\), and the livestreaming channel, \(p_2^{ca,*}\), are

\({\text {Define}}\alpha _1=\frac{2(c \beta _1^2 - b_2 \beta _1 \beta _2)}{b_2 c k + c \beta _1^2 - 2 b_2 \beta _1 \beta _2}\) and \(\alpha _2=\frac{-2 b_1 b_2 k + c^2 k - 2 b_1 \beta _1^2 +3 c \beta _1 \beta _2 + \sqrt{(2 b_1 b_2 k - c^2 k + 2 b_1 \beta _1^2 -3 c \beta _1 \beta _2)^2 - 4 c \beta _1 \beta _2 (-2 b_1 b_2 k + 2 c^2 k - 2 b_1 \beta _1^2 +2 c \beta _1 \beta _2)}}{2 c \beta _1 \beta _2}\). Next, we explore the impacts of the commission rate s on the pricing decisions under an agency selling agreement and obtain the following proposition.

Proposition 4

The impacts of the commission rate s on the pricing strategies under the agency selling agreement are as follows:

-

(i)

When \(0\le \alpha \le \alpha _1\), then \(p_1^{ca,*}\) is increasing in s; when \(\alpha _1 \le \alpha \le 1\), then \(p_1^{ca,*}\) is decreasing in s.

-

(ii)

When \(0\le \alpha \le \alpha _2\), then \(p_2^{ca,*}\) is increasing in s; when \(\alpha _2 \le \alpha \le 1\), then \(p_2^{ca,*}\) is decreasing in s.

Proposition 4 shows that the impact of the commission rate on the prices for the online platform and the live streaming channel depend on the agency fee. When the agency fee is relatively low, the prices for the online platform and the live streaming channel both increase in the commission rate, but when the agency fee is high, the prices for the two channels both decrease in the commission rate. This result is counterintuitive. The reason for this result may be that a high agency fee encourages the upstream supplier to sell fewer goods through the platform and more goods via live streaming; thus, although the supplier still reduces its retail price for the live streaming channel to prevent excessive product surplus when the commission rate increases, the retail price for the online platform falls accordingly.

5 Analysis and results for the fixed commission case

5.1 Centralized supply chain

In the centralized supply chain, the total profits, the pricing strategy, and the effort level of the internet celebrity, regardless of whether the reselling or agency selling agreement is chosen by the platform, are the same as in the commission rate case. Thus, we proceed directly to a consideration of the case of a decentralized supply chain.

5.2 Decentralized supply chain

The procedure for obtaining the solution is the same as that in the commission rate case, so we proceed directly to the ultimate results in this section.

5.2.1 Equilibrium results under a reselling agreement

5.2.1.1 The internet celebrity’s problem

For the internet celebrity, when the supplier pays her a fixed commission, her profit function is \(F-\frac{1}{2}ke^2\). Clearly, the greater the effort she makes, the less profit she obtains. Thus, the optimal effort level for the celebrity is 0, i.e., \(e_d^{fr,*}=0\).

5.2.1.2 The online platform’s problem

Substituting the optimal effort level \(e_d^{fr,*}=0\) into Eq. (5), we obtain the profit function for the online platform under the reselling agreement, denoted as \(\Pi _p^{fr}=(p_1-w)(a_1-b_1 p_1+c_1 p_2)\); then, we have the following lemma and proposition:

Lemma 7

Given the supplier’s prices w and \(p_2\), the optimal retail price for the online platform is

Proposition 5

The optimal retail price for the online platform \(p_1^{fr,*}(w,p_2)\) is increasing in the wholesale price w and the retail price for the live streaming channel \(p_2\).

Proposition 5 shows that the optimal retail price for the platform depends on the supplier’s wholesale price and the retail price for the live streaming channel, both of which have a positive impact on the platform’s optimal pricing. In addition, the basic demand associated with the platform also significantly affects its pricing.

5.2.1.3 The supplier’s problem

By substituting \(e^{fr,*}\) and \(p_1^{fr,*}(w,p_2)\) into Eq. (4), we can obtain the supplier’s profit as follows:

Before computing the optimal \(w^*\) and \(p_2^*\), we first analyze the concavity of \(\Pi _s^{cr}(w,p_2)\) with respect to w and \(p_2\) and obtain the following results.

Lemma 8

\(\Pi _s^{fr}(w, p_2)\) is jointly concave in w and \(p_2\), and the supplier’s optimal prices are

5.2.2 Equilibrium results under the agency selling agreement

In the agency selling agreement, the celebrity’s optimal effort level is also 0, and the optimal retail prices for the online platform and the live streaming channel are determined by the upstream supplier. Using backward induction, we substitute the optimal effort level \(e^{f\!a,*}=0\) into Eq. (5), then we have the following result.

Lemma 9

The supplier’s profit function \(\Pi _s^{f\!a}(p_1,p_2)\) is jointly concave in \(p_1\) and \(p_2\), and the optimal pricing strategies are

Lemma 9 shows that the optimal retail prices for the online platform and the live streaming channel depend only on the agency fee, as the other system parameters are fixed and that the agreement between the supplier and the online platform also affects the pricing decision associated with the live streaming channel.

6 Numerical analysis

To analytically illustrate the mathematical results obtained in this paper, we conduct a numerical analysis in this section. For the sake of realism and consistency with the model assumptions, we set the baseline parameter values to \(a=500,\ b_1=1,\ b_2=1,\ c=0.3,\ \beta _1=2,\ \beta _2=0.5,\ \theta =0.8,\ k=10,\ s=30,\ \alpha =0.05, and\ F=2000\). To prevent symbol congestion, we use the superscripts “cr” and “ca” to indicate the case of the reselling or the agency selling agreement, respectively, in the commission rate case and the superscripts “fr” and “fa" in the fixed commission case. Next, we further investigate the impact of the system parameters on the supply chain members’ decisions. Specifically, in Sect. 6.1, we explore the impact of the agency fee \(\alpha\) on the choice of selling agreement in the presence of the live streaming sales channel. In Sect. 6.2, we investigate the impact of the self-effort coefficient on the supply chain members’ profits. Next, we observe the impact of the payment methods on the supply chain members’ profits and strategies in Sect. 6.3. Finally, we explore the impact of the internet celebrity’s level of influence on the supply chain members’ profits and on the selection of the selling agreement in Sect. 6.4.

6.1 The impact of the agency fee

In our model, we assume that the choice between the reselling and the agency selling agreements is determined by the online platform. In practice, the selling agreement needs to be negotiated between the platform and the supplier. Therefore, in this section, we consider the impact of the agency fee \(\alpha\) charged by the platform on the use of the agency and reselling agreements as well as on profits when the supplier and the platform are alternately the Stackelberg leader. In contrast with previous studies, this section considers the selection of the selling agreement (i.e., reselling or agency selling) by the supply chain members in the presence of a live streaming sales channel. Figure 3a shows that there is a threshold in the agency fee \(\hat{\alpha } (\approx 0.22)\); when the agency fee is below this threshold, the platform prefers the reselling agreement, while for cases in which the agency fee is above the threshold \(\hat{\alpha }\), the platform prefers agency selling, regardless of whether the supplier pays a commission rate or fixed commission to the internet celebrity. This result is in line with reality. The reason for this result is that when the platform is the Stackelberg leader, a lower agency fee pushes the platform to choose a reselling agreement, while a higher agency fee enables the platform to obtain more profits through agency selling than reselling. One interesting result is that when the agency fee is sufficiently high, approximately greater than 0.8, the platform’s profits when a commission rate is paid decrease rapidly; that is, it is not true that a higher agency fee always leads to higher profit for the platform under the agency selling agreement. The reason for this result is that the supplier may significantly increase his wholesale price to offset his losses when the agency fee is too high, which reduces the profit of the platform. From Fig. 3b, we can see that there is also a threshold in the agency fee when the supplier is the Stackelberg leader, \(\overline{\alpha } (\approx 0.43)\); when the agency fee is below this threshold, the supplier chooses the agency selling agreement, while when the agency fee is above this threshold, the supplier chooses the reselling agreement. This result is intuitive and practical. Clearly, the agency fee \(\alpha\) only affects the live streaming channel under the agency selling agreement. From Fig. 3c, we can see that the celebrity’s profit increases as the agency fee increases under an agency selling agreement and a commission rate payment structure. The reason is that when the agency fee increases, the supplier sells fewer goods on the platform and more goods through the live streaming channel. We initially set the fixed commission to \(F = 2000\). In this situation, the internet celebrity always prefers a fixed commission.

Based on the numerical results, we know that there is a range of potential agency fees within which both the supplier and the platform choose the agency selling agreement. Outside this interval, however, it is difficult for the supplier and the platform to reach a consensus on the selling agreement. In addition, the agency fee also has a significant influence on the celebrity’s profit under a commission rate payment structure when an agency selling agreement is signed between the supplier and the platform.

6.2 The impact of self-effort coefficient

In this section, we change the self-effort coeffcient \(\beta _1\), and hold the other parameters fixed, which is equivalent to changing the ratio of the self-effort coeffcient to the cross-effort coeffcient. We explore the impact of a change in this ratio on the supply chain members’ profits. From Fig. 4a, we can see that the ratio \(\frac{\beta _1}{\beta _2}\) has relatively little impact on the platform’s profit, and the platform’s profit is unchanged in the case of a fixed commission payment structure. The reason is that the optimal effort level is 0 in the case of a fixed commission, which further reduces the impact of the effort coefficient on the demand associated with the platform. In addition, since the baseline agency fee is \(\alpha = 0.05\), the profit obtained by the platform through agency selling is much less than that obtained through reselling. Fig. 4b shows that the supplier’s profit increases as \(\beta _1\) increases. The reason is that the larger \(\beta _1\) is, the greater is the optimal level of effort for the internet celebrity, which causes the net demand from the two channels to increase and in turn increases the profits of the upstream supplier. Figure 4c suggests that there exists a threshold in the effort coefficient for the live streaming channel such that when this effort coefficient is lower than the threshold, the celebrity prefers the fixed commission payment structure, while when the effort coefficient for the live streaming channel is larger than the threshold, the celebrity prefers a commission rate payment structure in the context of a reselling agreement. Moreover, the effort coefficient has very little effect on the celebrity’s profit.

6.3 The impact of the payment methods

In this section, we first explore the impact of the commission rate on the profits of the supply chain members to evaluate the impact of the commission rate on the choice of selling strategy made by the supply chain members. The results are presented in Fig. 5. We find that when the supplier pays a per-unit commission to the celebrity: (1) The platform’s profits increase as the commission rate increases, and the growth in platform profits under the reselling agreement is greater than that under the agency selling agreement. The reason for this result may be that the higher commission rate encourages the upstream supplier to sell more goods through the platform, thus increasing the profit of the platform. (2). The supplier’s profits decrease as the commission rate increases under both the reselling agreement and the agency selling agreement. Such a result is obvious. (3). The celebrity’s profits first increase and then decrease as the commission rate increases. This result is counterintuitive. The reason behind this result may be that when the commission rate is high enough, the supplier sells most of his goods through the platform, resulting in fewer products being sold through the live streaming channel. In addition, for the celebrity, when the commission rate is relatively low, she prefers the fixed commission method; when the commission rate is relatively high, she often prefers the commission rate method. However, when the commission rate is sufficiently high, she may in turn prefer a fixed commission payment structure. In other words, the commission rate charged by the celebrity should not be too large; otherwise, the gains will not outweigh the losses.

Clearly, the fixed commission F has no influence on the platform’s decision. Thus, we only investigate the impact of the fixed commission F on the supplier and the celebrity’s profits. Figure 6 shows that if a fixed commission payment structure is agreed upon by the supplier and the internet celebrity, the supplier’s profit decreases as the fixed commission increases, while the celebrity’s profits increase as the fixed commission increases. Furthermore, the supplier prefers the fixed commission payment structure when the fixed commission is relatively low and prefers the commission rate payment structure when the fixed commission is relatively high. However, the preference of the internet celebrity over the commission payment structures is the opposite of that of the supplier. These results conform to reality. From our numerical experiments, we find that it advantageous for the supplier to choose the fixed commission payment structure only when the fixed commission is relatively low. Otherwise, it is better to choose the commission rate structure. According to a news story from some time ago, the famous Chinese actor Xiaochun Chen charged a fixed fee of 500,000 yuan to help a business sell its goods. Only 5000 yuan worth of products were sold as a result.

6.4 The impact of the internet celebrity’s influence

In this section, we consider the impact of the internet celebrity on the supply chain members’ profits. Recall that in our paper, \(\theta\) represents the proportion of demand associated with the platform out of the total overall demand in the market. We assume that the overall demand in the market comes from two channels: the platform and the live streaming sales channel. Clearly, the larger \(\theta\) is, the smaller the overall demand from the live streaming sales channel; that is, the lower the influence of the internet celebrity. From Fig. 7a, we find that the platform’s profit increases as \(\theta\) increases, and Fig. 7c shows that when the supplier and the internet celebrity reach an agreement on a commission rate, the internet celebrity’s profit decreases as \(\theta\) increases. One interesting result embedded within Fig. 7b is that the supplier’s profit first decreases and then increases as \(\theta\) increases. In other words, as the leader of the supply chain system, when the supplier chooses to have the internet celebrity sell goods via live streaming, he should not choose a celebrity with moderate influence but rather either a celebrity with an extremely large following or a celebrity with little influence. This result is counterintuitive, and the reason behind it may be that when the celebrity has an extremely large following, i.e., the basic demand associated with the live streaming channel is large, even if the celebrity does not exert much effort to sell the products, her strong fan base will generate a higher demand associated with the live streaming channel. When the celebrity has fewer followers, she will exert more effort to attract fans to buy. Only those celebrities whose influence tends to be moderate do not have enough fans and do not exert sufficient effort to sell goods on the live streaming channel. In such a case, the sales volume from the live streaming channel will be low, thus reducing the profits of the supplier.

7 Conclusions and managerial implications

The choice between reselling and agency selling on an online platform has always been a research topic of great interest in both academia and industry. With the rapid development of the “Internet plus”, sales models are becoming increasingly diversified. Especially after the outbreak of COVID-19, the development of live streaming sales has been particularly rapid and has had a significant impact on the sales models and management practices used by enterprises. To the best of our knowledge, this paper is the first to discuss the choice between agency selling and reselling agreements in the presence of a live streaming sales channel. By constructing a stylized game model, we analyze a multiechelon supply chain system with an upstream supplier, an online platform, and a live streaming sales channel. The upstream supplier can sell his products through an online platform or a live streaming sales channel, and the online platform can choose to offer a reselling agreement or an agency selling agreement to the supplier. In addition, this paper considers different commission payment structures that the supplier can offer to the internet celebrity: one is the payment of a per-unit commission rate for each unit of product sold by the celebrity, and the other is the payment of a fixed commission to the celebrity regardless of how many goods she sells. Through backward induction, we derive the equilibrium strategies under the different commission payment structures and selling agreements.

The results of this study show that the characteristics of the live streaming sales channel have a significant impact on the equilibrium strategies within the system. Specifically, we find that under a reselling agreement, the optimal retail price for the platform decreases with an increase in the commission rate paid to the internet celebrity, and the retail price for the live streaming channel always increases with an increase in the commission rate, while the relationship between the wholesale price and the commission rate depends on the ratio of the coefficient on the internet celebrity’s effort that is associated with the live streaming channel to that associated with the online platform. The results imply that when the commission rate is high, the platform should reduce its retail price, although the retail price of the live streaming channel is also high in this case. When the above ratio is small, the supplier should increase the wholesale price charged to the platform with an increase in the commission rate. When the ratio of the two coefficients on effort is large, the supplier should reduce the wholesale price charged to the platform when the commission rate increases. Under the agency selling agreement, there is a threshold in the agency fee. The impact of the commission rate on the supplier’s pricing strategy on one side of the threshold is the opposite of that on the other side.

In addition, we identify the conditions under which an agency selling or reselling agreement should be selected in the presence of a live streaming sales channel. Specifically, there is a threshold in the agency fee. When the agency fee is below the threshold, the platform tends to choose the reselling agreement, while it prefers the agency selling agreement when the agency fee is higher than the threshold, regardless of whether the supplier pays the internet celebrity a commission rate or a fixed commission. For the supplier, there is a separate threshold in the agency fee. When the agency fee is below the threshold, the supplier chooses agency selling; otherwise, the supplier selects reselling. In other words, when the agency fee falls within a specific interval, both the supplier and the platform choose the agency selling agreement, but outside this interval, it is difficult for the supplier and the platform to reach a consensus on which selling agreement to choose. Therefore, in practice, the supplier and the platform will negotiate an agency fee that is acceptable to both parties. An interesting result is that when the agency fee is high enough, i.e., approximately greater than 0.8, the profit of the platform in the commission rate case declines rapidly. The reason for this result is that when the agency fee is sufficiently high, the supplier may significantly increase his wholesale price to offset this loss, which reduces the profits of the platform. Therefore, when the agency fee is set by the platform, the platform will not choose a particularly high agency fee; otherwise, the losses outweigh the gains.

Furthermore, we find that the platform’s profit decreases with an increase in the internet celebrity’s influence and that the celebrity’s profit increases as her influence increases under a commission rate payment structure. Interestingly, the supplier’s profit first decreases and then increases as the celebrity’s influence increases. Thus, in practice, when the supplier chooses to hire an internet celebrity to sell goods via live streaming, he should not choose a celebrity with a moderate influence but should instead choose a celebrity with either an extremely large following or little influence. The reason behind this result is that when the celebrity has a smaller following, she will exert more effort to attract fans to buy the product, and when the celebrity has an extremely large following, even if she does not exert much effort to sell the products, her strong fan base will generate more demand for the live streaming channel. Only those celebrities whose influence tends to be moderate will neither have enough fans nor exert enough effort to sell goods on the live streaming channel. As a result, the sales volume of live streaming channel will be low, thus reducing the profits of the supplier.

Finally, we hope to point out some limitations of the current work and provide some ideas for future research. First, in our paper, the demand function is deterministic. Future research can consider the case in which demand is stochastic. Second, we assume that supply chain members only choose one sales model: agency selling or reselling. In the future, we can assume that supply chain members can choose a hybrid strategy; that is, they can employ both the agency selling and the reselling models. Third, this paper assumes that the internet celebrity can obtain revenue by promoting a product via live streaming. It would also be interesting to consider a cost-sharing or revenue-sharing contract between the celebrity and the supplier.

Notes

For convenience, in what follows, we use “he" to refer to the supplier and “she" to refer to the internet celebrity involved in the live streaming.

References

Abhishek, V., Jerath, K., & Zhang, Z. J. (2016). Agency selling or reselling? Channel structures in electronic retailing. Management Science, 62(8), 2259–2280.

Chen, H., Zhang, S., Shao, B., Gao, W., & Xu, Y. (2022). How do interpersonal interaction factors affect buyers’ purchase intention in live stream shopping? The mediating effects of swift guanxi. Internet Research, 32(1), 335–361.

Chen, L., Nan, G., Li, M., Feng, B., Liu, Q., (2022). Manufacturer’s online selling strategies under spillovers from online to offline sales. Journal of the Operational Research Society, pp. 1–24.

Chen, X., Li, B., Chen, W., Wu, S., (2021a). Influences of information sharing and online recommendations in a supply chain: Reselling versus agency selling. Annals of Operations Research, pp. 1–40.

Chen, Z., Fan, Z. P., & Zhao, X. (2021). Offering return-freight insurance or not: Strategic analysis of an e-seller’s decisions. Omega, 103, 102447.

Chen, Z., Ji, X., Li, M., & Li, J. (2022). How corporate social responsibility auditing interacts with supply chain information transparency. Annals of Operations Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-022-04601-x

Clement Addo, P., Fang, J., Asare, A. O., & Kulbo, N. B. (2021). Customer engagement and purchase intention in live-streaming digital marketing platforms. The Service Industries Journal, 41(11–12), 767–786.

Daily, C., (2017). Xiaomi releases mi 6, speeds up offline expansion. Avaliable at: http://m.chinadaily.com.cn/en/2017-04/19/content_28999144.html

Fu, F., Chen, S., Yan, W., (2021). Implications of e-tailers’ transition from reselling to the combined reselling and agency selling. Electronic Commerce Research, pp. 1–36.

Gao, X., Xu, X. Y., Tayyab, S. M. U., & Li, Q. (2021). How the live streaming commerce viewers process the persuasive message: An elm perspective and the moderating effect of mindfulness. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 49, 101087.

Geng, R., Wang, S., Chen, X., Song, D., & Yu, J. (2020). Content marketing in e-commerce platforms in the internet celebrity economy. Industrial Management and Data Systems, 120(3), 464–485.

Ha, A. Y., Tong, S., & Wang, Y. (2021). Channel structures of online retail platforms. Manufacturing and Service Operations Management. https://doi.org/10.1287/msom.2021.1011.

He, P., Wang, Z., Shi, V., & Liao, Y. (2021). The direct and cross effects in a supply chain with consumers sensitive to both carbon emissions and delivery time. European Journal of Operational Research, 292(1), 172–183.

Hu, M., & Chaudhry, S. S. (2020). Enhancing consumer engagement in e-commerce live streaming via relational bonds. Internet Research, 30(3), 1066–2243.

Hua, G., Wang, S., & Cheng, T. E. (2010). Price and lead time decisions in dual-channel supply chains. European Journal of Operational Research, 205(1), 113–126.

Ji, X., Li, G., & Sethi, S. P. (2022). How social communications affect product line de- sign in the platform economy. International Journal of Production Research, 60(2), 686–703.

Kang, K., Lu, J., Guo, L., & Li, W. (2021). The dynamic effect of interactivity on customer engagement behavior through tie strength: Evidence from live streaming commerce platforms. International Journal of Information Management, 56, 102251.

Kwark, Y., Chen, J., & Raghunathan, S. (2017). Platform or wholesale? a strategic tool for online retailers to benefit from third-party information. MIS Quarterly, 41(3), 763–785.

Li, G., Li, L., Sethi, S. P., & Guan, X. (2019). Return strategy and pricing in a dual-channel supply chain. International Journal of Production Economics, 215, 153–164.

Li, G., Nan, G., Wang, R., Tayi, G. K., (2022). Retail strategies for e-tailers in live streaming commerce: When does an influencer marketing channel work? Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3998665 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3998665

Li, G., Tian, L., & Zheng, H. (2021). Information Sharing in an Online Marketplace with Co-opetitive Sellers. Production and Operations Management, 30(10), 3713–3734. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.13460

Li, G., Zhang, L., Guan, X., & Zheng, J. (2016). Impact of decision sequence on reliability enhancement with supply disruption risks. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 90, 25–38.

Li, G., Zheng, H., & Liu, M. (2020). Reselling or drop shipping: Strategic analysis of E-commerce dual-channel structures. Electronic Commerce Research, 20(3), 475–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10660-019-09382-3

Li, Q., Wang, Q., & Song, P. (2019). The effects of agency selling on reselling on hybrid retail platforms. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 23(4), 524–556.

Li, R., Lu, Y., Ma, J., & Wang, W. (2021). Examining gifting behavior on live streaming platforms: An identity-based motivation model. Information and Management, 58(6), 103406.

Lin, Y., Yao, D., & Chen, X. (2021). Happiness begets money: Emotion and engagement in live streaming. Journal of Marketing Research, 58(3), 417–438.

Liu, B., Guo, X., Yu, Y., & Tian, L. (2021). Manufacturer’s contract choice facing competing downstream online retail platforms. International Journal of Production Research, 59(10), 3017–3041.

Liu, W., Yan, X., Li, X., & Wei, W. (2020). The impacts of market size and data-driven marketing on the sales mode selection in an internet platform based supply chain. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 136, 101914.

Lu, B., & Chen, Z. (2021). Live streaming commerce and consumers’ purchase intention: An uncertainty reduction perspective. Information and Management, 58(7), 103509.

Lu, S., Yao, D., Chen, X., & Grewal, R. (2021). Do larger audiences generate greater revenues under pay what you want? evidence from a live streaming platform. Marketing Science, 40(5), 964–984.

Lv, J., Yao, W., Wang, Y., Wang, Z., & Yu, J. (2021). A game model for information dissemination in live streaming e-commerce environment. International Journal of Communication Systems, 35(1), e5010.

Mao, Z., Du, Z., Yuan, R., & Miao, Q. (2022). Short-term or long-term cooperation between retailer and MCN? New launched products sales strategies in live streaming e-commerce. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 67, 102996.

Pu, X., Sun, S., & Shao, J. (2020). Direct selling, reselling, or agency selling? Manufacturer’s online distribution strategies and their impact. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 24(2), 232–254.

Pu, X., Zhang, S., Ji, B., & Han, G. (2021). Online channel strategies under different offline channel power structures. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 60, 102479.

Sun, C., & Ji, Y. (2022). For better or for worse: Impacts of IoT technology in e-commerce channel. Production and Operations Management, 31(3), 1353–1371.

Sun, Y., Shao, X., Li, X., Guo, Y., & Nie, K. (2019). How live streaming influences purchase intentions in social commerce: An it affordance perspective. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 37, 100886.

Svart, A., (2018). The use of live streaming in marketing. Ph.D. thesis, Bachelor’s Thesis Programme International Business Administration, Tallinn.

Wongkitrungrueng, A., & Assarut, N. (2020). The role of live streaming in building consumer trust and engagement with social commerce sellers. Journal of Business Research, 117, 543–556.

Wongkitrungrueng, A., Dehouche, N., & Assarut, N. (2020). Live streaming commerce from the sellers’ perspective: Implications for online relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing Management, 36(5–6), 488–518.