Abstract

With the growing importance of sustainable farming and increasing fluctuations in the price of agricultural produce, the choice of nature of farming and participation in a cooperative has become critical. This paper examines farmers’ decision of adopting organic farming and participating in cooperative institutions to market their produce. We formulate a two-stage strategic game model whereby two farmers first choose a technique of production of their crops followed by a decision regarding the mechanism by which to sell their products to cope with the environment of uncertain agricultural prices. We extend the two-stage process to find out conditions under which it would be profitable for a farmer to produce organic crop. We found that farmers are more likely to produce organic crop if they can sell their produce through a cooperative. Our analytical results show that incremental costs of organic production, the operational cost of running cooperatives and crop’s price volatility can be crucial in influencing farmers’ choice of production techniques of and marketing institutions. In particular, we found that when it is easier for farmers to participate in cooperative, they tend to choose organic production technique. To empirically support the findings, we analyzed the weekly transactions of 65 Fruits and Vegetables during 2017 in six different regions in the United States. We found that regions with higher number of cooperatives registered higher transactions in organic crop.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Willer, Helga (February 10, 2016) “Organic Agriculture Worldwide 2016: Current Statistics” (PDF). FiBL and IFOAM Organics International.

Since we have identical farmers, we will drop subscript i in \(q_{\gamma \delta }\) for convenience in notation.

Refer to “Appendix 1”.

Region-wise cooperative distribution is reported in Table 8 in “Appendix 6”.

References

Abdul-Rahaman, A., & Abdulai, A. (2018). Do farmer groups impact on farm yield and efficiency of smallholder farmers? Evidence from rice farmers in northern Ghana. Food Policy, 81, 95–105.

Acs, S., Berentsen, P., Huirne, R., & Van Asseldonk, M. (2009). Effect of yield and price risk on conversion from conventional to organic farming. Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 53(3), 393–411.

Adamtey, N., Musyoka, M. W., Zundel, C., Cobo, J. G., Karanja, E., Fiaboe, K. K., et al. (2016). Productivity, profitability and partial nutrient balance in maize-based conventional and organic farming systems in Kenya. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 235, 61–79.

Ademe, Y. A., Guda, S. T., & Lemma, A. B. L. (2020). Contribution of organic inputs to maize productivity in the Eastern African region: A quantitative synthesis. Agriculture and Natural Resources, 54(1), 64–73.

von Arb, C., Bünemann, E., Schmalz, H., Portmann, M., Adamtey, N., Musyoka, M., et al. (2020). Soil quality and phosphorus status after nine years of organic and conventional farming at two input levels in the central highlands of Kenya. Geoderma, 362, 114112.

Bacon, C. (2005). Confronting the coffee crisis: Can fair trade, organic, and specialty coffees reduce small-scale farmer vulnerability in Northern Nicaragua? World Development, 33(3), 497–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.10.002.

Bakhtavoryan, R., Poghosyan, A., Lopez, J. A., & Ogunc, A. (2019). An empirical analysis of household demand for organic and conventional flour in the united states: Evidence from the 2014 Nielsen Homescan data. Journal of Agribusiness, 37(2), 97–116.

Becchetti, L., Conzo, P., & Gianfreda, G. (2012). Market access, organic farming and productivity: The effects of fair trade affiliation on Thai farmer producer groups. Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 56(1), 117–140.

Buck, D., Getz, C., & Guthman, J. (1997). From farm to table: The organic vegetable commodity chain of Northern California. Sociologia Ruralis, 37(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9523.00033.

Darnhofer, I., Schneeberger, W., & Freyer, B. (2005). Converting or not converting to organic farming in Austria: Farmer types and their rationale. Agriculture and Human Values, 22(1), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-004-7229-9.

De Ponti, T., Rijk, B., & van Ittersum, M. K. (2012). The crop yield gap between organic and conventional agriculture. Agricultural Systems, 108, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2011.12.004.

Dempsey, J. (2006). A case study of institution building to link Ethiopian co-operative coffee producers to international markets. ACDI/VOCA, Ethiopia: Tech. rep.

Dessart, F. J., Barreiro-Hurlé, J., & van Bavel, R. (2019). Behavioural factors affecting the adoption of sustainable farming practices: A policy-oriented review. European Review of Agricultural Economics, 46(3), 417–471.

Franco, J. (2009). An analysis of the California market for organically grown produce. American Journal of Alternative Agriculture, 4(01), 22. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0889189300002587

Ghali-Zinoubi, Z., & Toukabri, M. (2019). The antecedents of the consumer purchase intention: Sensitivity to price and involvement in organic product: Moderating role of product regional identity. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 90, 175–179.

Gil, J. M., Gracia, A., & Sánchez, M. (2000). Market segmentation and willingness to pay for organic products in Spain. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 3(2), 207–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7508(01)00040-4.

Hansen, B., Alrøe, H. F., & Kristensen, E. S. (2001). Approaches to assess the environmental impact of organic farming with particular regard to Denmark. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 83(1–2), 11–26.

Home, R., Indermuehle, A., Tschanz, A., Ries, E., & Stolze, M. (2019). Factors in the decision by swiss farmers to convert to organic farming. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 34(6), 571–581.

Issahaku, G., & Abdulai, A. (2019). Adoption of climate-smart practices and its impact on farm performance and risk exposure among smallholder farmers in Ghana. Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics.

Jouzi, Z., Azadi, H., Taheri, F., Zarafshani, K., Gebrehiwot, K., Van Passel, S., & Lebailly, P. (2017). Organic farming and small-scale farmers: Main opportunities and challenges. Ecological Economics, 132, 144–154.

Kirchmann, H., Bergström, L., Kätterer, T., Andrén, O., & Andersson, R. (2009). Can organic crop production feed the world? In: Organic crop production—Ambitions and limitations, pp. 39–72. Springer.

Kleemann, L., & Effenberger, A. (2010). Price transmission in the pineapple market: What role for organic fruit? http://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/32812/1/627759637.pdf.

Lampkin, N. H. (1994). Organic farming: Sustainable agriculture in practice. In N. H. Lampkin & S. Padel (Eds.), The economics of organic farming: An international perspective (pp. 3–9). Wallingford: Centre for Agricultural Bioscience International (CABI).

Li, X., Peterson, H. H., & Xia, T. (2018). Demand for organic fluid milk across marketing channels. Agricultural and Resource Economics Review, 47(3), 505–532.

Ma, W., & Abdulai, A. (2019). Ipm adoption, cooperative membership and farm economic performance. China Agricultural Economic Review.

Ma, W., Renwick, A., Yuan, P., & Ratna, N. (2018). Agricultural cooperative membership and technical efficiency of apple farmers in China: An analysis accounting for selectivity bias. Food Policy, 81, 122–132.

Meemken, E. M., & Qaim, M. (2018). Organic agriculture, food security, and the environment. Annual Review of Resource Economics.

Métouolé Méda, Y. J., Egyir, I. S., Zahonogo, P., Jatoe, J. B. D., & Atewamba, C. (2018). Institutional factors and farmers’ adoption of conventional, organic and genetically modified cotton in Burkina Faso. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 16(1), 40–53.

Mzoughi, N. (2011). Farmers adoption of integrated crop protection and organic farming: Do moral and social concerns matter? Ecological Economics, 70(8), 1536–1545.

Oberholtzer, L., Dimitri, C., & Greene, C. (2005). Price premiums hold on as US organic produce market expands. Economic Research Service, Washington (DC): US Department of Agriculture.

Omotayo, O., Chukwuka, K., et al. (2009). Soil fertility restoration techniques in sub-Saharan Africa using organic resources. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 4(3), 144–150.

Palaniappan, S., & Annadurai, K. (2018). Organic farming theory & practice. Scientific Publishers.

Raper, K. C., Black, J. R., Hogberg, M., & Hilker, J. H. (2005). Assessing bottlenecks in vertically organized beef systems. Journal of Food Distribution Research, 36(1), 151–155.

Raynolds, L. T. (2000). Re-embedding global agriculture: The international organic and fair trade movements. Agriculture and Human Values, 17(3), 297–309. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007608805843

Reganold, J. P., & Wachter, J. M. (2016). Organic agriculture in the twenty-first century. Nature Plants, 2(2), 1–8.

Rigby, D., & Cáceres, D. (2001). Organic farming and the sustainability of agricultural systems. Agricultural Systems, 68(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0308-521X(00)00060-3.

Rodriguez, J. M., Molnar, J. J., Fazio, R. A., Sydnor, E., & Lowe, M. J. (2009). Barriers to adoption of sustainable agriculture practices: Change agent perspectives. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 24(01), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742170508002421.

Roesch-McNally, G. E., Basche, A. D., Arbuckle, J., Tyndall, J. C., Miguez, F. E., Bowman, T., & Clay, R. (2018). The trouble with cover crops: Farmers’ experiences with overcoming barriers to adoption. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 33(4), 322–333.

Schneeberger, W., Darnhofer, I., & Eder, M. (2002). Barriers to the adoption of organic farming by cash-crop producers in Austria. American Journal of Alternative Agriculture, 17(1), 24–31.

Seufert, V., Ramankutty, N., & Foley, J. A. (2012). Comparing the yields of organic and conventional agriculture. Nature, 485(7397), 229–232.

Sivaranjani, S., & Rakshit, A. (2019). Organic farming in protecting water quality. Organic Farming (pp. 1–9).

Stopes, C., Lord, E., Philipps, L., & Woodward, L. (2002). Nitrate leaching from organic farms and conventional farms following best practice. Soil Use and Management, 18, 256–263.

Su, Y., Brown, S., & Cook, M. (2013). Stability in organic milk farm prices: A comparative study. Ph.D. thesis, Washington, DC. http://scholarworks.uvm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1491&context=graddis.

Verhaegen, I., & Van Huylenbroeck, G. (2001). Costs and benefits for farmers participating in innovative marketing channels for quality food products. Journal of Rural Studies, 17(4), 443–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0743-0167(01)00017-1.

Wander, M., Traina, S., Stinner, B., & Peters, S. (1994). Organic and conventional management effects on biologically active soil organic matter pools. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 58(4), 1130–1139.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

I am grateful to Manaswini Bhalla and Prakash Awasthy for the comments they provided on the draft of this article.

Appendices

Appendices

1.1 Appendix 1

The prices are assumed to be normally distributed. Therefore, profit received by farmers also follows normal distribution with mean \(\varPi _\mu\) and variance \(\varPi _\sigma ^2\).

We define the expected utility as follows:

Where \(f(\varPi )= \left[ \frac{1}{(2\pi \varPi _\sigma ^2)^{1/2}}\right] e^{-\left( \frac{(\varPi -\varPi _\mu )^2}{2\varPi _\sigma ^2}\right) }\) represents the PDF (probability density function).

Hence,

We take the monotonic transformation of Eq. (7) as follows:

Equation (8) denotes the expected utility of each farmer.

1.2 Appendix 2

1.2.1 Both grow non-organic crop

1.2.2 Both farmers sell to a cooperative

We define the expected utility of farmer selling through cooperative as follows:

where \({P_N^\mu }\) denotes the average price of non-organically produced crop, \(\sigma {_N}^2\) denotes the variance of the price of non-organically crop, \(q_{NC}\) is the amount of crop sold by each farmer through cooperative, and F represents the operational cost of the cooperative. Both farmers are assumed to be homogeneous, therefore, each farmer shares half of the operating the cooperative.

By substituting the value of \(\sigma {_N}^2 = 0\) in Eq. (10), we get:

\(q_{NC}*\), the utility maximizing output level, is \(\frac{{P_N^\mu }}{2a}\).

By substituting \(q_{NC}*\) in (10) we derive expected utility of each farmer which is equal to \(\frac{{{P_N^\mu }}^2}{4a} -\frac{F}{2})\).

1.2.3 Both farmers sell to private market

Farmer’s objective function when both of the sell everything to private market is:

where \(q_{NW}\) is the quantity produced and sold by each farmer in the private market.

The utility maximizing quantity for each farmer selling to private market is \(\frac{{P_N^\mu }}{2a +\alpha \sigma {_N}^2}\).

And, the expected utility is equal to \(\frac{1}{2}\left( \frac{{{P_N^\mu }}^2}{2a +\alpha \sigma {_N}^2}\right)\).

1.2.4 One farmer sells through cooperative and another in private market

When only one farmer participates in the cooperative, he/she incurs the entire operational cost. Therefore, the expected utility function is represented by the following Eq. (11):

Expected utility maximizing output level:

Expected utility of the farmer from selling through cooperative:

Expected utility from selling in private market is represented as follows:

The utility maximizing quantity level of farmer selling in private market is represented by \(\frac{{P_N^\mu }}{2a +\alpha \sigma {_N}^2}\).

And, the expected utility is \(\frac{1}{2}\left( \frac{{{P_N^\mu }}^2}{2a +\alpha \sigma {_N}^2}\right)\).

We represent these payoffs using a \(2\times 2\) matrix:

Cooperative | Private | |

|---|---|---|

Cooperative | \((\frac{{{P_N^\mu }}^2}{4a}-\frac{F}{2})\), \((\frac{{{P_N^\mu }}^2}{4a}-\frac{F}{2})\) | \((\frac{{{P_N^\mu }}^2}{4a}-F)\), \(\frac{1}{2}\left( \frac{{{P_N^\mu }}^2}{2a +\alpha \sigma {_N}^2}\right) \) |

Private | \(\frac{1}{2}\left( \frac{{{P_N^\mu }}^2}{2a +\alpha \sigma {_N}^2}\right) \), \((\frac{{{P_N^\mu }}^2}{4a}-F)\) | \(\frac{1}{2}\left( \frac{{{P_N^\mu }}^2}{2a +\alpha \sigma {_N}^2}\right) \), \(\frac{1}{2}\left( \frac{{{P_N^\mu }}^2}{2a +\alpha \sigma {_N}^2}\right) \) |

Nash equilibrium:

Conditions | Nash Equilibrium | |

|---|---|---|

Case 1 | \(\frac{\alpha \sigma {_N}^2 {{P_N^\mu }}^2}{4a(2a+\alpha \sigma {_N}^2 )} \ge F\) | (Cooperative, Cooperative) |

Case 2 | \(\frac{\alpha \sigma {_N}^2 {{P_N^\mu }}^2}{4a(2a+\alpha \sigma {_N}^2 )} \le F \le \frac{\alpha \sigma {_N}^2 {{P_N^\mu }}^2}{2a(2a+\alpha \sigma {_N}^2 )}\) | (Cooperative, Cooperative);(Private, Private) |

Case 3 | \(\frac{\alpha \sigma {_N}^2 {{P_N^\mu }}^2}{2a(2a+\alpha \sigma {_N}^2 )} \le F\) | (Private, Private) |

1.3 Appendix 3

1.3.1 Both grow organic crop

The average price and the variance of organically produced crop are assumed to be \({P_O^\mu }\) and \(\sigma {_O}^2\), respectively. The additional cost incurred by organic crop (in controlling for pesta and diseases), also called the cost of effort, is denoted by \(C(\epsilon )= bq_{\gamma \delta }^2\).

1.3.2 Both participate in cooperative

The following equation represents the objective function of each farmer when both of them participates in a cooperative:

where \(q_{OC}\) is each farmer’s produce to be sold via cooperative.

By substituting \(\sigma {_O}^2 = 0\) in Eq. (17)

The utility maximizing output level ‘\(q_{OC}*\)’ is \(\frac{{P_O^\mu }}{2(a+b)}\) for each farmers.

Again, by substituting \(q_{OC}*\) in the expected utility function, we get expected utility equal to \(\frac{{{P_O^\mu }}^2}{4(a+b)} - \frac{F}{2}\).

1.3.3 Both sell in private market

The expected utility of each farmer:

where \(q_{OW}\) is the quantity produced and sold by each farmer in the private market.

The expected utility maximizing output level of farmer selling in private market is represented by \(\frac{{P_O^\mu }}{2a + 2b +\alpha \sigma {_O}^2}\).

Expected utility of each farmer equals to \(\left( \frac{{{P_O^\mu }}^2}{2(2a + 2b + \alpha \sigma {_O}^2})\right)\).

1.3.4 One farmer sells in cooperative and another to private market

When there is only one farmer in the cooperative, he/she incurs the entire operational cost. Therefore, following Eq. (18), expected utility function of such farmer is:

Expected utility maximizing output level:

The expected utility of farmer selling in private market is represented by:

Expected utility received by each farmer equals to \(\left( \frac{{{P_O^\mu }}^2}{2(2a + 2b + \alpha \sigma {_O}^2})\right)\).

We can represent these payoffs using a \(2\times 2\) matrix:

Cooperative | Private | |

|---|---|---|

Cooperative | \(\left( \frac{{{P_O^\mu }}^2}{4(a+b)} - \frac{F}{2}\right) \), \(\left( \frac{{{P_O^\mu }}^2}{4(a+b)} - \frac{F}{2}\right) \) | \(\left( \frac{{{P_O^\mu }}^2}{4(a+b)} - F\right) \), \(\left( \frac{{{P_O^\mu }}^2}{2(2a + 2b + \alpha \sigma {_O}^2)}\right) \) |

Private | \(\left( \frac{{{P_O^\mu }}^2}{2(2a + 2b + \alpha \sigma {_O}^2)}\right) \), \(\left( \frac{{{P_O^\mu }}^2}{4(a+b)} - F\right) \) | \(\left( \frac{{{P_O^\mu }}^2}{2(2a + 2b + \alpha \sigma {_O}^2)}\right) \), \(\left( \frac{{{P_O^\mu }}^2}{2(2a + 2b + \alpha \sigma {_O}^2)}\right) \) |

Nash equilibrium for the game:

Conditions | Nash Equilibrium | |

|---|---|---|

Case 1 | \(\frac{\alpha \sigma {_O}^2 {{P_O^\mu }}^2}{4(a+b)(2a + 2b+\alpha \sigma {_O}^2)}\ge F\) | (Cooperative, Cooperative) |

Case 2 | \(\frac{\alpha \sigma {_O}^2 {{P_O^\mu }}^2}{4(a+b)(2a+2b+\alpha \sigma {_O}^2 )} \ge F \ge \frac{\alpha \sigma {_O}^2 {{P_O^\mu }}^2}{2(a+b)(2a+2b+\alpha \sigma {_O}^2)}\) | (Cooperative, Cooperative);(Private, Private) |

Case 3 | \(\frac{\alpha \sigma {_O}^2 {{P_O^\mu }}^2}{2(2a+2b+\alpha \sigma {_O}^2)} \le F\) | (Private market, Private market) |

1.4 Appendix 4

1.4.1 Choice of farming technique

Let \(T^N_1 = \frac{\alpha \sigma {_N}^2 {{P_N^\mu }}^2}{4a(2a+\alpha \sigma {_N}^2 )}\) and \(T^N_2 = 2T^N_1\).

\(T^O_1 = \frac{\alpha \sigma {_O}^2 {{P_O^\mu }}^2}{4(a+b)(2a + 2b+\alpha \sigma {_O}^2)}\) and \(T^O_2 = 2T^O_1\)

Four possible situations arises:

(1) \(T^N_1 < T^O_1\) and \(T^N_2 < T^O_1\)

(2) \(T^N_1 < T^O_1\) and \(T^N_2 > T^O_1\)

(3) \(T^N_1 > T^O_1\) and \(T^N_1 > T^O_2\)

(4) \(T^N_1 > T^O_1\) and \(T^N_1 < T^O_2\)

However, \(T^N_1 < T^O_1\) and \(T^N_2 < T^O_1\) will hold true \(\forall \alpha\) such that,

and,

The above scenarios represent five possible Nash equilibria for different ranges of“F”.

(a) \(F \le T^N_1\): A range of very low F. Nash equilibrium is (Cooperation, Cooperation).

(b) \(T^N_1 \ge F \le T^N_2\): low F. Nash equilibrium for non-organic crop is {(Cooperation, Cooperation); (Private, Private)}, whereas for organic crop is (Cooperation, Cooperation)

(C) \(T^N_2 \ge F \le T^O_1\): moderate F. Nash equilibrium for non-organic crop is (Private, Private), whereas for organic crop is (Cooperation, Cooperation).

(d) \(T^O_1 \ge F \le T^O_2\) i.e., high F. Nash equilibrium for non-organic crop is (Private, Private), whereas for organic crop is {(Cooperation, Cooperation); (Private, Private)}.

(e) \(F \ge T^O_2\) i.e., very high F. Nash equilibrium is (Private, Private).

Case 1 \(F \le T^N_1\) (Both participates in Cooperative)

Organic(O) | Non-organic (N) | |

|---|---|---|

Organic(O) | \(\left( \frac{{{P_O^\mu }}^2}{4(a+b)} - \frac{F}{2}\right) \), \(\left( \frac{{{P_O^\mu }}^2}{4(a+b)} - \frac{F}{2}\right) \) | \(\left( \frac{{{P_O^\mu }}^2}{4(a+b)} - F\right) \), \((\frac{{{P_N^\mu }}^2}{4a}- F)\) |

Non-organic (N) | \((\frac{{{P_N^\mu }}^2}{4a}-F)\), \(\left( \frac{{{P_O^\mu }}^2}{4(a+b)} - F\right) \) | \((\frac{{{P_N^\mu }}^2}{4a}-\frac{F}{2})\), \((\frac{{{P_N^\mu }}^2}{4a}-\frac{F}{2})\) |

For any value of \(\frac{{P_O^\mu }^2}{{P_N^\mu }^2}\ge \frac{(a+b)}{a}\) and \(F\le \frac{a{P_O^\mu }^2-{P_N^\mu }^2(a+b)}{2(a+b)}\), a rational producer will always choose organic crop and sell to cooperative.

Case 2 \(T^N_1<F<T^N_2\) (Non-organic Farmer sell through cooperative or private market and Organic Farmer through Cooperative)

The equilibrium for the game will be same as in case 1 if farmers producing non-organic crop sell through cooperative. But, the game changes as below if he sells through private market.

Organic(O) | Non-organic (N) | |

|---|---|---|

Organic(O) | \(\left( \frac{{{P_O^\mu }}^2}{4(a+b)} - \frac{F}{2}\right) \), \(\left( \frac{{{P_O^\mu }}^2}{4(a+b)} - \frac{F}{2}\right) \) | \(\left( \frac{{{P_O^\mu }}^2}{4(a+b)} - F\right) \), \(\frac{1}{2}\left( \frac{{{P_N^\mu }}^2}{2a +\alpha \sigma {_N}^2}\right) \) |

Non-organic (N) | \(\frac{1}{2}\left( \frac{{{P_N^\mu }}^2}{2a +\alpha \sigma {_N}^2}\right) \), \(\left( \frac{{{P_O^\mu }}^2}{4(a+b)} - F\right) \) | \(\frac{1}{2}\left( \frac{{{P_N^\mu }}^2}{2a +\alpha \sigma {_N}^2}\right) \), \(\frac{1}{2}\left( \frac{{{P_N^\mu }}^2}{2a +\alpha \sigma {_N}^2}\right) \) |

If \(\frac{2a({P_O^\mu }^2-{P_N^\mu }^2)-2b{P_N^\mu }^2+\alpha \sigma _N^2{P_O^\mu }^2}{4(a+b)(2a+\alpha \sigma _N^2)} \ge F\), N.E. is both producing organic crop and selling in cooperative. If \(\frac{2a({P_O^\mu }^2-{P_N^\mu }^2)-2b{P_N^\mu }^2+\alpha \sigma _N^2{P_O^\mu }^2}{4(a+b)(2a+\alpha \sigma _N^2)}\le F \le \frac{2a({P_O^\mu }^2-{P_N^\mu }^2)-2b{P_N^\mu }^2+\alpha \sigma _N^2{P_O^\mu }^2}{2(a+b)(2a+\alpha \sigma _N^2)}\), the equilibrium is either both producing organically and selling through cooperative or both producing non-organically and selling though Private market. Since both producing organic and selling in cooperative in pareto optimal, we assume farmers to produce organic and sell in cooperative

For \(\frac{2a({P_O^\mu }^2-{P_N^\mu }^2)-2b{P_N^\mu }^2+\alpha \sigma _N^2{P_O^\mu }^2}{2(a+b)(2a+\alpha \sigma _N^2)}\le F\), the equilibrium will be both producing non-organically and selling through Private market.

Case 3 \(T^N_2<F<T^O_1\) (Farmer producing non-organic sells to private market and Farmer producing organic sells to Cooperative)

Equilibrium is same as case 2.

Case 4 \(T^O_1<F<T^O_2\) (Farmer producing non-organic sells to private market and farmer producing Organic sells to either Cooperative or Private market)

Nash equilibrium is same as Case 3 when farmer producing organic crop sells in cooperative.

However, the game matrix follows as below if he/she sells to private market:

Organic(O) | Non-organic (N) | |

|---|---|---|

Organic(O) | \(\left( \frac{{{P_O^\mu }}^2}{2(2a + 2b + \alpha \sigma {_O}^2)}\right) \), \(\left( \frac{{{P_O^\mu }}^2}{2(2a + 2b + \alpha \sigma {_O}^2)}\right) \) | \(\left( \frac{{{P_O^\mu }}^2}{2(2a + 2b + \alpha \sigma {_O}^2)}\right) \), \(\frac{1}{2}\left( \frac{{{P_N^\mu }}^2}{2a +\alpha \sigma {_N}^2}\right) \) |

Non-organic (N) | \(\frac{1}{2}\left( \frac{{{P_N^\mu }}^2}{2a +\alpha \sigma {_N}^2}\right) \), \(\left( \frac{{{P_O^\mu }}^2}{2(2a + 2b + \alpha \sigma {_O}^2)}\right) \) | \(\frac{1}{2}\left( \frac{{{P_N^\mu }}^2}{2a +\alpha \sigma {_N}^2}\right) \), \(\frac{1}{2}\left( \frac{{{P_N^\mu }}^2}{2a +\alpha \sigma {_N}^2}\right) \) |

If \(\frac{{P_O^\mu }^2}{{P_N^\mu }^2} > \frac{2a+2b+ \alpha \sigma _O^2}{(2a+\alpha \sigma _N^2)}\), N.E. is both of them producing organic crop and selling to Private market. This condition will always hold true if \(\frac{\sigma _N^2}{\sigma _O^2}\ge \frac{a}{(a+b)}\).

Case 5 \(F \ge T^O_2\) (Both farmers selling through the Private market)

Equilibrium remains same as case 4.

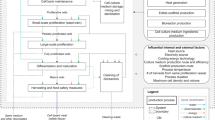

The results of the entire game are summarized in Fig. 4.

1.5 Appendix 5

1.5.1 A comparative analysis

Total quantity produced | Total utilities | |

|---|---|---|

\(F \le \frac{2a({P_O^\mu }^2-{P_N^\mu }^2)-2b{P_N^\mu }^2+\alpha \sigma _N^2{P_O^\mu }^2}{2(a+b)(2a+\alpha \sigma _N^2)}\) | \(\frac{{P_O^\mu }}{(a+b)}\) | \(\left( \frac{{{P_O^\mu }}^2}{2(a+b)} - F\right) \) |

\(\frac{2a({P_O^\mu }^2-{P_N^\mu }^2)-2b{P_N^\mu }^2+\alpha \sigma _N^2{P_O^\mu }^2}{2(a+b)(2a+\alpha \sigma _N^2)} \le F \le \frac{\alpha \sigma _O^2{P_O^\mu }^2}{4(a+b)(2a+2b+\alpha \sigma _O^2)} \) | \(\left( \frac{2{P_N^\mu }}{2a +\alpha \sigma {_N}^2}\right) \) | \(\left( \frac{{{P_N^\mu }}^2}{2a +\alpha \sigma {_N}^2}\right) \) |

\(F \ge \frac{\alpha \sigma _O^2{P_O^\mu }^2}{4(a+b)(2a+2b+\alpha \sigma _O^2)}\) | \(\frac{2{P_O^\mu }}{2a + 2b +\alpha \sigma {_O}^2}\) | \(\left( \frac{{{P_O^\mu }}^2}{(2a + 2b + \alpha \sigma {_O}^2})\right) \) |

Let \(A =\left( \frac{{{P_O^\mu }}^2}{2(a+b)} - F\right)\) , \(B= \left( \frac{{{P_N^\mu }}^2}{2a +\alpha \sigma {_N}^2}\right)\) and \(C=\left( \frac{{{P_O^\mu }}^2}{(2a + 2b + \alpha \sigma {_O}^2})\right)\)

Hence, \(A\ge B\)

For \(a>0\), \(b>0\) and \(\frac{{P_N^\mu }^2}{{P_O^\mu }^2} \ge \frac{2 a +\alpha {\sigma _N^2}}{2 a+2 b+ \alpha {\sigma _O^2}}\), \(A\ge B\ge C\).

Also, for \(b<\frac{\alpha ({\sigma _N^2-\sigma _O^2})}{2}\), \(\frac{{P_O^\mu }}{(a+b)}\ge \frac{2{P_N^\mu }}{2a +\alpha \sigma {_N}^2}\ge \frac{2{P_O^\mu }}{2a + 2b +\alpha \sigma {_O}^2}\)

1.6 Appendix 6

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Haldar, T., Damodaran, A. Can cooperatives influence farmer’s decision to adopt organic farming? Agri-decision making under price volatility. Environ Dev Sustain 24, 5718–5742 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01679-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01679-4