Abstract

Offshore outsourcing has grown as a form of industrial organisation to increase profitability of firms. However, offshoring may be less lucrative than envisaged, due to the presence of hidden costs. We study the strategic interaction amongst onshore Cournot firms in the decision to offshore when they receive signals about offshore hidden costs. The analysis helps suggest policy implications for countries which are potential offshoring locations. We find the precision of signals and the range of possible hidden costs to be crucial in determining offshoring destinations. Updating of information about hidden costs leads to different equilibria including herding in offshoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Offshore outsourcing refers to sourcing of inputs for production from a vendor located in a different country(Sabherwal 1999)

The precision gives the probability that the signal is correct. The signals for the two firms are independent and hence the precisions do not have common priors. The signals are exogenous to the model.

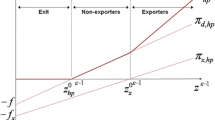

Producing in a Cournot framework, firm 2 may end up producing more(less) than the market demand when firm 1 faces low(high) hidden costs and hence may bear a loss. Hence it is optimal for firm 2 to be a Stackelberg follower. We show that in this period firm 1 may choose to reveal the true costs of production or to pool so as not to reveal the true costs depending on profitability and firm 2’s beliefs.

This is what can be seen in reality in the case of German firms offshoring activities to Austria rather than India. India with its lower fixed(contractible) costs of production turns out to be less competitive than Austria given that cultural and language differences push up the higher bound of its hidden costs.

References

Antras P (2003) Firms, contracts, and trade structure. Q J Econ 118(4):1375–1418

Barthelemy J (2001) The hidden costs of IT outsourcing. MIT Sloan Management Review

Baruch Y, Hind P (2000) Survivor syndrome - a management myth?. J Manag Psychol Emerald 15(1):29–45

Borga M, Zeile W (2004) International fragmentation of production and intrafirm trade of US multinational comapnies. Bureau Of Economic Analysis Working paper No. WP2004-02

Chamley C, Gayle D (1994) Information revelation and strategic delay in a model of investment. Econometrica 62(5):1065–1085

Davison D (2004) Top 10 risks of offshore outsourcing. CIO

DiamondCluster (2004) 2004 Global IT outsourcing study. DiamondCluster International

Goolsby K (2002) Offshore is not offhand. Recommendations for effective offshore outsourcing, White Paper. Everest Group, Dallas

Grossman G, Helpman E (2002) Integration versus outsourcing in industry equilibrium. Q J Econ 117(1):85–120

Grossman G, Helpman E (2003) Outsourcing vs FDI in industry equilibrium. J Eur Econ Assoc 1(2-3):317–327

Karamouzis F (2002) Debunking the myths of offshore IT service offerings. ID number DF-15-5315 (March 21). Gartner Inc., Stamford

Milgrom P, Roberts J (1982) Predation, reputation, and entry deterrence. J Econ Theory 27(2):280–312

Navaretti GB, Venables AJ (2006) Multinational firms in the world economy. Economics Books. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Overby S (2003) The hidden costs of offshore outsourcing. CIO Magazine

Qu Z, Brocklehurst M (2003) What will it take for China to become a competitive force in offshore outsourcing? An analysis of the role of transaction costs in supplier selection. J Inf Technol 18:53–67

Sabherwal R (1999) The role of trust in outsourced IS development projects. Commun ACM 42(2):80–86

Yeats AJ (2001) Just how big is global production sharing?. In: Arndt SW, Kierzkowski H (eds) Fragmentation: new production patterns in the world economy. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 108–143

Zhang J (1997) Strategic delay and the onset of investment cascades. RAND J Econ 28(1):188–205

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the help of Prof. Soumyanetra Munshi in guiding to formalise this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

A version of this paper is available as an Indian Institute of Management Bangalore Working Paper No.: 370.

Appendices

Appendix A: Proof of Observation 1

We simplify equation 8 and write it as:

where, \(F(C_{h},C_{d})=[P^{HS}-(\bar {C}+C_{h})]\) and P HS is a function of C d and C h . \(G(C_{h},C_{d})=[P^{HC}(C_{d},C_{h})-(\bar {C}+C_{h})]\) and similarly for the others.

Now, that gives the lower bound for \(q_{1}^{HS}\) i.e.

Differentiating this expression wrt C l we get:

Now, for a given demand function and the costs of production C h , \(q_{1}^{HS}\) is the profit maximising Stackelberg output. For any increases in output the revenues increase less than the costs. Hence at the given cost C h it becomes more and more unprofitable to produce more output. Hence for conventional demand functions with decreasing marginal revenue this expression comes out to be positive.

So, as C l decreases, the RHS reduces in value. Hence the inequality holds more strongly. Thus the higher is (C h − C l ) the stronger the possibility of the high type to reveal his true hidden cost. Hence observation 1 stands proved.

Appendix B: Proof of Observation 2

Qualitative proof of one IC binding in the pooling equilibrium: ICH:

i.e.:

ICL:

i.e.:

Now it may be noted that LHS of the ICH is less than LHS of ICL. Similarly RHS of ICH is less than RHS of ICL. Thus, the IC of the high type alone guarantees the low type IC as well. It is easy to note that as C l increases profitability of the low hidden cost type falls. Hence leaving C h unchanged, one gets a situation where both inequalities are simultaneously satisfied.

Proof of Observation 2:

Following on from above:

For a lower C h ,the LHS increases and we have strict inequality. Hence the ICs become stronger. [Proved] □

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mukherjee, D. Hidden Costs of Offshore Outsourcing: an Analysis of Offshoring Decisions. J Ind Compet Trade 18, 303–318 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-017-0259-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-017-0259-y