Abstract

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) may be a common issue in primary care in the UK, but there have been no studies of all-cause PTSD in general samples of attenders in this country. The current paper thus explores the extent and distribution of probable PTSD among patients attending general practices in England. Cross-sectional survey data from adult patients (n = 1058) attending 11 general practices in southwest England were analysed. Patients were recruited from waiting rooms and completed anonymous questionnaires, including measures of depression, anxiety and risky alcohol use. Current probable PTSD was measured using the 4-item Primary Care PTSD Scale (PC-PTSD). Results indicated 15.1% of patients that exhibited probable PTSD (PC-PTSD ≥ 3), with higher levels observed in practices from deprived areas. There were 53.8% of patients with probable PTSD that expressed the desire for help with these issues. The analyses suggested that rates were lowest among older adults, and highest among patients who were not in cohabitating relationships or were unemployed. Measures of anxiety and depression were associated with 10-fold and 16-fold increases in risk of probable PTSD, respectively, although there were no discernible associations with risky drinking. Such preliminary findings highlight the need for vigilance for PTSD in routine general practice in the UK, and signal a strong need for additional research and attention in this context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a psychiatric condition that is linked with high levels of functional impairment and poor quality of life (Schnurr & Lunney, 2016), as well as physical health problems (Pacella, Hruska, & Delahanty, 2013). The disorder may develop following exposure to potentially traumatic events including serious accidents or disasters, exposure to war and conflict, sexual or physical assault (including intimate partner violence; IPV), and life threatening illnesses (Darves-Bornoz et al., 2008). Negative psychological reactions are common sequelae to such events and are often transitory. However, for a significant minority of survivors these symptoms may progress into a disorder characterised by intrusive re-experiencing of the event (through intrusive thoughts, visual or auditory memories and dreams), avoidance of reminders (e.g. places, people and thoughts), alterations in cognitions or mood (e.g. shame, guilt, negative cognitions), and hyperarousal (e.g. hypervigilance, exaggerated startle response; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Population-based studies indicate around one third of adults in England report at least one major traumatic event in their lifetime, and 4.4% suffer from probable PTSD in the past month (McManus, Bebbington, Jenkins, Brugha, & NHS Digital, & UK Statistics Authority, 2016).

Treatment guidelines from the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, 2018) recommend trauma-focussed therapies (which target traumatic experiences and memories) as first-line treatments for PTSD, while also recognising benefits from some pharmacotherapies when patients are unwilling or unable to engage with psychological therapies. However, studies suggest around half of PTSD sufferers fail to receive mental health treatment (McManus et al., 2016), which can be delayed for many years due to stigma and low recognition of the disorder (Iversen et al., 2011; Kantor, Knefel, & Lueger-Schuster, 2017). Conversely, PTSD is associated with high use of generalist healthcare services (Kartha et al., 2008), including primary care, and may be encountered commonly in these environments. Effective treatments for PTSD can only be delivered if relevant conditions are recognised (NICE, 2018), and as such, there may be an important role for primary care in improving the uptake and delivery of evidence-based therapies.

Guidelines from NICE recommend inquiring about PTSD when people are involved in major disasters, and also among high risk populations including refugees and asylum seekers (NICE, 2018). However, international evidence suggests that rates of PTSD in generalist medical settings, such as routine primary care, may also be significant and indicate an important context for identification and intervention strategies. Much of this research has been situated in military contexts in the U.S., where there is an expansive system of specific care for current and ex-service personnel and family members, while smaller numbers of studies have addressed civilian services. Systematic reviews of this literature have indicated prevalence estimates which vary widely across studies and settings (from 2 to 39%; Greene, Neria, & Gross, 2016), with a quantitative synthesis (based on k = 15 studies of screening tools from the U.S.) indicating a mean prevalence of 13.5% for PTSD in primary care (Spoont et al., 2015). The small number of studies from outside the U.S. estimate around 8% of men (11% of women) attending primary care exhibit PTSD in Israel (Taubman-Ben-Ari, Rabinowitz, Feldman, & Vaturi, 2001), and comparable figures of 9% among men (17% among women) in Spain (Gómez-Beneyto, Salazar-Fraile, Martí-Sanjuan, & Gonzalez-Luján, 2006). In contrast, we know of only one relevant study in UK primary care that has investigated rates of PTSD, and this identified 32% of general practice patients with a history of myocardial infarction (n = 111) who also exhibited probable PTSD (Jones, Chung, Berger, & Campbell, 2007).

There is a strong need for additional studies of PTSD in primary care settings which are situated across international jurisdictions. In large part, this is because evidence from cross-national studies indicates that traumatic events are distributed unequally across countries (including high income countries), while there is also international variation in overall levels of PTSD and particularly high rates observed in high income countries (Koenen et al., 2017). Furthermore, there are important differences in the nature and organisation of health services across countries which means that existing U.S. evidence has limited generalisability to other jurisdictions. In the UK, for example, there is a publicly funded system of universal health care, called the National Health Service (NHS), which incorporates primary care services that are characterised by near universal registration of patients with a single practice, and services which are free at the point of delivery in most cases (Roland, Guthrie, & Thomé, 2012). While economic and health inequalities would seem to have widened in the U.S. (Dickman, Himmelstein, & Woolhandler, 2017), there is evidence that such universal health systems contribute towards reduced social and socio-economic disparities in access to medical services (Asaria et al., 2016; Cookson et al., 2017), thereby increasing utilisation by disadvantaged populations that may be particularly vulnerable to major types and frequencies of traumatic events (e.g. violence victimisation) and PTSD (Frissa et al., 2013; Roberts, Gilman, Breslau, Breslau, & Koenen, 2011). Furthermore, the availability of universal health care in the UK, in particular, has limited the need for a system of specific care for ex-service personnel, such that most military veterans who report combat trauma and related mental health problems will also obtain care in the public system (versus veteran-specific services that are the main provider of care for veteran populations in the U.S.; Macmanus & Wessely, 2013). In the context of scant evidence that relates to the UK, as well as increased emphasis on responses to trauma-related mental health in the context of COVID-19 (Horesh & Brown, 2020), the aims of the current paper were to:

-

(1)

Provide new data on the extent of probable PTSD among patients attending general practices in one region of England; and

-

(2)

Explore the distribution of probable PTSD and variability according to socio-demographic and mental health characteristics which may indicate vulnerable groups.

Methods

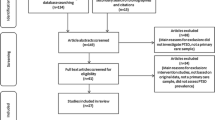

Participants and Procedure

This study reports on analyses of data that informed a broader study of addictive behaviours and mental health in primary care (Cowlishaw, Gale, Gregory, McCambridge, & Kessler, 2017). Briefly, the target population comprised patients attending general practices in the Bristol region of southwest England. Eleven practices were sampled according to population deprivation and patient characteristics. Deprivation levels were quantified using the Index of Multiple Deprivation 2015, which is the official measure of relative deprivation for neighbourhoods in England, which is based on area-level information regarding income, employment, education, health and disability, crime, barriers to housing and services, and the living environment (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2015). This identified four practices from highly deprived areas (top 30% for deprivation in England), two practices in areas of low deprivation (bottom 30%), and three practices in a moderate band (middle 40% for deprivation). One additional practice was included which provided care to young adults in a student health service, while another practice provided services to a homeless population. Patients aged over 18 and attending for any reason were eligible, but were excluded if they were unable to understand English, required immediate medical attention, or were unable to give consent. Patients were approached by a researcher in waiting rooms and asked to complete anonymous questionnaires. These were returned in the waiting room or using pre-paid envelopes, and yielded n = 1058 questionnaires. Although surveys were anonymous, participants who identified concerns they wished to address with a healthcare professional were advised during the consent process to discuss these with their GP, or else contact other local help services. Sample characteristics are displayed in Table 1, while further details can be found elsewhere (Cowlishaw et al., 2017).

Measures

Probable PTSD was measured using the Primary Care PTSD Scale (PC-PTSD; Prins et al., 2003), which comprises four items (see Table 2) reflecting the PTSD symptom clusters according to the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), and scored on a binary scale (0 = no, 1 = yes). The measure was developed in a U.S. Veterans Affairs (VA) setting (Prins et al., 2003), while subsequent studies in civilian primary care indicate superiority relative to other brief measures, and strong psychometric properties (AUC values > 0.90) that are similar to longer tools (Freedy et al., 2010). An optimal cut-off score of 3 was shown to correctly classify 83% of patients, and produce sensitivity and specificity values of 85% and 82%, respectively, while positive predictive values and negative predictive values were 38% and 98% (Freedy et al., 2010). Patients providing affirmative responses to PC-PTSD items were also asked if they wanted help with these issues (no, yes, or yes but not today) using an item based on the help question from the Case-finding Help Assessment Tool (Goodyear-Smith, Arroll, & Coupe, 2009).

Brief measures identified other mental health concerns that are commonly recognised in primary care. These included the 2-item Whooley scale for depression (Whooley, Avins, Miranda, & Browner, 1997) and the GAD-2 (Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams, Monahan, & Löwe, 2007) for anxiety, which are recommended in UK primary care (Kendrick & Pilling, 2012). Recent evidence syntheses indicate that scores on the Whooley scale (1 +) and GAD-2 (3 +) are associated with sensitivity (specificity) values of 0.95 (0.65) (Bosanquet et al., 2015) and 0.80 (0.81) (Plummer, Manea, Trepel, & McMillan, 2016), respectively. Risky alcohol use was measured using the consumption items from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C; Bush, Kivlahan, McDonell, Fihn, & Bradley, 1998). Psychometric studies of the AUDIT-C indicate that scores of 5 + are associated with sensitivity and specificity values of 0.74 and 0.85, respectively with reference to risky drinking (including at-risk drinking, alcohol misuse or dependence; Rumpf, Hapke, Meyer, & John, 2002).

Data Analyses

Data-file preparation was conducted using SPSS 21, while substantive analyses were conducted using STATA 14. Modest levels of missing data for PC-PTSD items (ranging from 10 to 12%) were addressed using zero-fill techniques, thus assuming no PTSD symptoms, while missing data for additional variables (which ranged from around 5% for depression to 13% for alcohol) were managed through pairwise deletion. This approach to missing data reflects the primary interest in providing conservative estimates of probable PTSD, while other measures are presented for comparative purposes. Descriptive analyses were produced for the PC-PTSD items and the aggregate scale score (for all patients and stratified across practices from areas of high, moderate and low levels of deprivation), as well as the help item. Tests of associations with probable PTSD and patient characteristics comprised Pearson χ2-tests with logistic regression models to explore significant effects. The latter specified probable PTSD as an endogenous variable, and with patient characteristics treated as exogenous. These were evaluated in separate models, which thus estimated bivariate associations through Odds Ratios (ORs) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs).

Results

Table 2 indicates frequencies for PC-PTSD items, as well as the total scale, and indicates between 18 and 25% of patients who endorsed individual items, while the criterion of ≥ 3 on the PC-PTSD identified 15.1% of patients with probable PTSD.

The highest levels of probable PTSD were observed within practices from highly deprived areas (19.0%, 95% CI 15.3% to 23.4%), when compared to those characterised by moderate (10.9%, 95% CI 7.9% to 14.7%) and low deprivation levels (12.5%, 95% CI 8.4% to 18.2%). The difference between high and moderately deprived areas was statistically significant (non-overlapping confidence intervals indicate significant effects). Around 54% of all patients with probable PTSD indicated the desire for help with these symptoms, with almost 25% indicating the desire for help in the current consultation (and around 30% indicating the desire for help but not today).

Bivariate associations involving probable PTSD and patient socio-demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. These indicated significant associations with age, relationship and employment status. Logistic regression analyses indicated higher rates of probable PTSD among all age groups, relative to patients aged 65 + years (for example, patients aged 35–44 years exhibited a near seven-fold increase in probable PTSD when compared to those aged 65 or older: OR 6.58, 95% CI 3.11 to 13.92), and among patients who were single or divorced/separated/widowed/other, relative to those who were married or cohabitating (for example, patients who were single/never married exhibited a twofold increase in probable PTSD: OR 2.13, 95% CI 1.45 to 3.12). Patients who were unemployed exhibited more than twice the rate of probable PTSD relative to those employed full-time or part-time (OR 2.43, 95% CI 1.52 to 3.89).

Analyses of clinical characteristics are shown in Table 3, which indicates significant associations with probable PTSD and both depression and anxiety, but not risky alcohol use. As shown, there were n = 561 participants (53% of the sample) that scored 1 + on the Whooley scale for depression, and 26.4% (n = 148) of these patients exhibited probable PTSD. Logistic regression indicated that this represented a nearly 16-fold increase in probable PTSD, relative to patients scoring zero on the Whooley scale (OR 15.55, 95% CI 8.08 to 29.92). Comparable analyses of anxiety indicated a near tenfold increase in probable PTSD (OR 9.78, 95% CI 6.67 to 14.33).

Discussion

Around 15% of patients in general practice waiting rooms in one region of southwest England screened positive for probable PTSD, while the highest levels were observed in practices from highly deprived areas. Around half of all these patients with probable PTSD indicated the desire for help with their problems. Younger, unmarried, and unemployed patients were at increased risk of probable PTSD. There were very strong associations with both anxiety and depression, whereby almost half of patients who screened positive to the former, and a quarter of those indicating the latter, also reported probable PTSD.

The estimated rate of PTSD in this study was comparable to figures from U.S. research that has identified rates of 13.5% (on average) for PTSD in primary care (Spoont et al., 2015). This is notwithstanding differences in the nature of health care systems in these countries, which are universal and publicly funded in the UK, and are also characterised by other distinctive features (for example, there is universal registration of patients with a single general practice, while health care services are usually free at the point of delivery; Roland et al., 2012). Moreover, the observed rate of probable PTSD in this study was three times higher than figures for England overall (although comparisons with population-based studies should be viewed cautiously given use of more comprehensive measurements in the latter; McManus et al., 2016), and suggests significant overrepresentation in primary care. However, findings of higher rates of probable PTSD in practices from deprived areas indicates that such overall figures, which relate to primary care settings in general, may mask heterogeneity and increased rates among practices that serve disadvantaged populations. This aligns with U.S. studies that also identified particularly high rates of PTSD in primary care populations characterised low socio-economic status and high levels of trauma exposure (Liebschutz et al., 2007). The finding that over half of patients indicating probable PTSD expressed the desire for help was also high relative to studies using similar questions regarding other issues; for example, which indicate rates of wanting help ranging from 11% for problematic drinking to 57% for depression (Goodyear-Smith et al., 2009). As far as we know, this is the first study of receptivity of patients to help for PTSD in primary care, and thus provides evidence of the acceptability of questioning in this context. This extends prior research from veterans-specific health services in the U.S. that have examined the feasibility and acceptability of brief PTSD interventions in primary care (Pigeon, Allen, Possemato, Bergen-Cico, & Treatman, 2015).

Probable PTSD was lowest among adults aged 65 + years and patients who were married or cohabitating, and was elevated among the unemployed, and these findings are all consistent with results for England overall (McManus et al., 2016). Evidence of high rates among the unemployed also aligns with broader literature indicating that some traumatic events occur disproportionally among disadvantaged populations (Benjet et al., 2016), while subsequent mental health problems predict functional and work-related impairments (Wald & Taylor, 2009) that can interfere with employment. Associations with depression and anxiety also align with literature on PTSD comorbidity (Pietrzak, Goldstein, Southwick, & Grant, 2011). This includes substantial research on major depression, in particular, which indicates that these conditions co-occur frequently (Rytwinski, Scur, Feeny, & Youngstrom, 2013), and that comorbid PTSD predicts poor responses to depression treatment over time (Green et al., 2006). In conjunction with the current study, these findings suggest that PTSD is commonly associated with other common mental disorders, particularly anxiety and depression, and may complicate treatment of these conditions across health service environments including general practice. In contrast, there were no significant associations observed in this study with probable PTSD and risky alcohol use, which is generally inconsistent with prior research that has commonly identified positive links with PTSD and alcohol misuse (Debell et al., 2014). Although speculative, such differences may be due to the usage of the AUDIT-C in this study, which is a brief screen that infers risky drinking from patterns of alcohol consumption, and does not comprise a direct measure of harm or symptoms of alcohol dependence that have typically been addressed in prior studies (Debell et al., 2014).

Strengths and Limitations

The sample was large and was intended to approximate patients encountered routinely in primary care in the UK. However, it was derived from a small number of practices in a specific region of southwest England, and did not utilise systematic sampling strategies for practices or patients. As such, the findings may not generalise to other parts of the country, and may also be affected by selection bias. Furthermore, the data were collected prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and does not capture mental health problems that have resulted from this mass trauma (Horesh & Brown, 2020). The number of patients approached and declined to participate were not recorded. Clinical characteristics were measured using brief scales that overestimate significant mental health problems. Probable PTSD was measured using a brief screen which has excellent sensitivity and specificity (Freedy et al., 2010), but was not comprehensive or based on the most recent version of the DSM (the current study was designed prior to the publication of the DSM-5 version of the PC-PTSD; Prins et al., 2016). Furthermore, this screening measure was not calibrated to detect subthreshold PTSD symptoms, which are likely to be more common than full PTSD (Gillock, Zayfert, Hegel, & Ferguson, 2005) and may be the indicated targets of low intensity therapies delivered in primary care (Possemato, 2011). Zero-fill techniques were used to address missing data on the PTSD screen, which is likely to underestimate the rates of PTSD. Finally, the study did not evaluate events that were implicated in trauma symptoms (e.g. combat exposure, IPV), or the extent to which PTSD had been detected by clinicians.

Implications for Research and Practice

The study suggests around one in seven patients in routine primary care in England that exhibit probable PTSD, and thus indicates the importance of recognition in general practice in this national setting. The finding that more than half of patients with probable PTSD were receptive to help is striking, and suggests an acceptable role for general practitioners in improving engagement with PTSD treatment. Although this research did not consider the extent to which conditions were recognised by clinicians, we strongly suspect that many cases are undetected in primary care; for example, given studies of secondary care services which indicate less than 20% of patients with PTSD that are appropriately diagnosed (Zammit et al., 2018).

The current findings suggest that practitioners should be vigilant for PTSD in primary care settings generally in the UK, and particularly among patients who are unemployed or exhibit other mental health problems. This is consistent with so-called ‘case-finding’ approaches to depression and anxiety which are recommended in UK primary care (Kendrick & Pilling, 2012). The PC-PTSD was developed for primary care (Prins et al., 2016) and could be utilised regularly alongside measures of other mental disorders (Kendrick & Pilling, 2012) to inform questioning. When probable PTSD is identified, practitioners should be prepared to enquire about traumatic events and may benefit from relevant training (Lotzin et al., 2018). Patients reporting ongoing exposures to trauma should receive support and assistance to improve safety, while those who are no longer at risk should be referred to services delivering trauma-focussed therapies. The latter may be particularly important considerations for patients with other common mental disorders, such as depression and anxiety, given that pharmacotherapies are not recommended first-line treatments for PTSD (NICE, 2018), while depression and anxiety have been shown to improve when PTSD is addressed (van Minnen, Zoellner, Harned, & Mills, 2015). In the UK, these trauma-focussed therapies may be provided by private or third sector organisations, while NHS treatment can be obtained through Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) services (Clark, 2018). In this context, PTSD is classified as an ‘Anxiety and stress related disorder’ and may be addressed by high intensity therapists. Despite this, referrals to IAPT services for PTSD remain uncommon (comprising only 3.9% of referrals in 2016/2017; Community Mental Health Team, 2018), and this also highlights a potentially significant role for primary care in increasing uptake of these therapies.

In the context of the aforementioned limitations of this study, there is a strong need for additional research on the frequency and distribution of PTSD in primary care, which has a national focus and involves systematic sampling of practices and patients, as well as more comprehensive measurements. This research should also examine the preferences and acceptability of PTSD treatment strategies among patients identified in primary care. Furthermore, future research is also needed to demonstrate the feasibility and effectiveness of complex primary care interventions involving training and support for practice staff, and referral pathways to specialist services, which may be modelled on primary care responses to IPV (Feder et al., 2011). Alternative approaches in international studies that could also be considered include collaborative care models (Schnurr et al., 2013), as well as brief interventions delivered electronically (Possemato et al., 2016) or via behavioural health consultants embedded in primary care (Cigrang et al., 2017). The latter have received support in randomised studies (Cigrang et al., 2017), which also highlight the potential for brief forms of trauma-focussed therapy that may be optimised for general practice. These interventions in primary care would seem to have increased salience given pervasive threat and fear experiences that are associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, which is also important to view in terms of a mass disaster and from a trauma-informed perspective (Horesh & Brown, 2020).

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. Washington: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®) (5th ed.). Washington: American Psychiatric Association.

Asaria, M., Ali, S., Doran, T., Ferguson, B., Fleetcroft, R., Goddard, M., … Cookson, R. (2016). How a universal health system reduces inequalities: Lessons from England. J Epidemiol Community Health, 70(7), 637–643. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2015-206742.

Benjet, C., Bromet, E., Karam, E. G., Kessler, R. C., McLaughlin, K. A., Ruscio, A. M., … Koenen, K. C. (2016). The epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: Results from the World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Psychological Medicine, 46(2), 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715001981.

Bosanquet, K., Bailey, D., Gilbody, S., Harden, M., Manea, L., Nutbrown, S., et al. (2015). Diagnostic accuracy of the Whooley questions for the identification of depression: A diagnostic meta-analysis. British Medical Journal Open, 5(12), e008913. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008913.

Bush, K., Kivlahan, D. R., McDonell, M. B., Fihn, S. D., & Bradley, K. A. (1998). The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): An effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158(16), 1789–1795.

Cigrang, J. A., Rauch, S. A., Mintz, J., Brundige, A. R., Mitchell, J. A., Najera, E., … STRONG STAR Consortium. (2017). Moving effective treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder to primary care: A randomized controlled trial with active duty military. Families, Systems & Health: The Journal of Collaborative Family Healthcare, 35(4), 450–462. https://doi.org/10.1037/fsh0000315.

Clark, D. M. (2018). Realising the mass public benefit of evidence-based psychological therapies: The IAPT program. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 14, 159–183. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050817-084833.

Community Mental Health Team. (2018). Psychological Therapies: Annual report on the use of IAPT services England, further analyses on 2016–17 [PAS]. NHS Digital. Retrieved from https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/psychological-therapies-annual-reports-on-the-use-of-iapt-services/annual-report-2016-17-further-analyses.

Cookson, R., Mondor, L., Asaria, M., Kringos, D. S., Klazinga, N. S., & Wodchis, W. P. (2017). Primary care and health inequality: Difference-in-difference study comparing England and Ontario. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0188560.

Cowlishaw, S., Gale, L., Gregory, A., McCambridge, J., & Kessler, D. (2017). Gambling problems among patients in primary care: A cross-sectional study of general practices. The British Journal of General Practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 67(657), e274–e279. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp17X689905.

Darves-Bornoz, J.-M., Alonso, J., de Girolamo, G., Graaf, R. de, Haro, J.-M., Kovess-Masfety, V., … On Behalf of the ESEMeD/MHEDEA 2000 Investigators. (2008). Main traumatic events in Europe: PTSD in the European study of the epidemiology of mental disorders survey. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21(5), 455–462. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20357.

Debell, F., Fear, N. T., Head, M., Batt-Rawden, S., Greenberg, N., Wessely, S., & Goodwin, L. (2014). A systematic review of the comorbidity between PTSD and alcohol misuse. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49(9), 1401–1425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-014-0855-7.

Department for Communities and Local Government. (2015). The English Indices of Deprivation 2015: Statistical Release. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/465791/English_Indices_of_Deprivation_2015_-_Statistical_Release.pdf.

Dickman, S. L., Himmelstein, D. U., & Woolhandler, S. (2017). Inequality and the health-care system in the USA. The Lancet, 389(10077), 1431–1441. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30398-7.

Feder, G., Davies, R. A., Baird, K., Dunne, D., Eldridge, S., Griffiths, C., … Sharp, D. (2011). Identification and Referral to Improve Safety (IRIS) of women experiencing domestic violence with a primary care training and support programme: A cluster randomised controlled trial. The Lancet (London, England), 378(9805), 1788–1795. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61179-3.

Freedy, J. R., Steenkamp, M. M., Magruder, K. M., Yeager, D. E., Zoller, J. S., Hueston, W. J., & Carek, P. J. (2010). Post-traumatic stress disorder screening test performance in civilian primary care. Family Practice, 27(6), 615–624. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmq049.

Frissa, S., Hatch, S. L., Gazard, B., Fear, N. T., Hotopf, M., & SELCoH Study Team. (2013). Trauma and current symptoms of PTSD in a South East London community. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(8), 1199–1209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-013-0689-8.

Gómez-Beneyto, M., Salazar-Fraile, J., Martí-Sanjuan, V., & Gonzalez-Luján, L. (2006). Posttraumatic stress disorder in primary care with special reference to personality disorder comorbidity. The British Journal of General Practice, 56(526), 349–354.

Goodyear-Smith, F., Arroll, B., & Coupe, N. (2009). Asking for help is helpful: Validation of a brief lifestyle and mood assessment tool in primary health care. The Annals of Family Medicine, 7(3), 239–244. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.962.

Green, B. L., Krupnick, J. L., Chung, J., Siddique, J., Krause, E. D., Revicki, D., … Miranda, J. (2006). Impact of PTSD comorbidity on one-year outcomes in a depression trial. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(7), 815–835. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20279.

Greene, T., Neria, Y., & Gross, R. (2016). Prevalence, detection and correlates of PTSD in the primary care setting: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 23(2), 160–180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-016-9449-8.

Horesh, D., & Brown, A. D. (2020). Traumatic stress in the age of COVID-19: A call to close critical gaps and adapt to new realities. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(4), 331–335. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000592.

Iversen, A. C., van Staden, L., Hughes, J. H., Greenberg, N., Hotopf, M., Rona, R. J., … Fear, N. T. (2011). The stigma of mental health problems and other barriers to care in the UK Armed Forces. BMC Health Services Research, 11(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-11-31.

Jones, R. C., Chung, M. C., Berger, Z., & Campbell, J. L. (2007). Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder in patients with previous myocardial infarction consulting in general practice. The British Journal of General Practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 57(543), 808–810.

Kantor, V., Knefel, M., & Lueger-Schuster, B. (2017). Perceived barriers and facilitators of mental health service utilization in adult trauma survivors: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 52, 52–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.12.001.

Kartha, A., Brower, V., Saitz, R., Samet, J. H., Keane, T. M., & Liebschutz, J. (2008). The impact of trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder on healthcare utilization among primary care patients. Medical Care, 46(4), 388–393. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31815dc5d2.

Kendrick, T., & Pilling, S. (2012). Common mental health disorders—Identification and pathways to care: NICE clinical guideline. British Journal of General Practice, 62(594), 47–49. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp12X616481.

Koenen, K. C., Ratanatharathorn, A., Ng, L., McLaughlin, K. A., Bromet, E. J., Stein, D. J., … Kessler, R. C. (2017). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the World Mental Health Surveys. Psychological Medicine, 47(13), 2260–2274. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717000708.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W., Monahan, P. O., & Löwe, B. (2007). Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Annals of Internal Medicine, 146(5), 317–325.

Liebschutz, J., Saitz, R., Brower, V., Keane, T. M., Lloyd-Travaglini, C., Averbuch, T., et al. (2007). PTSD in urban primary care: High prevalence and low physician recognition. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22(6), 719–726. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0161-0.

Lotzin, A., Buth, S., Sehner, S., Hiller, P., Martens, M.-S., Pawils, S., … CANSAS Study Group. (2018). “Learning how to ask”: Effectiveness of a training for trauma inquiry and response in substance use disorder healthcare professionals. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 10(2), 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000269.

Macmanus, D., & Wessely, S. (2013). Veteran mental health services in the UK: Are we headed in the right direction? Journal of Mental Health, 22(4), 301–305. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2013.819421.

McManus, S., Bebbington, P., Jenkins, R., Brugha, T., & NHS Digital, & UK Statistics Authority. (2016). Mental health and wellbeing in England: Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014: A survey carried out for NHS Digital by NatCen Social Research and the Department of Health Sciences, University of Leicester. Leeds: NHS Digital.

NICE. (2018). Post-traumatic stress disorder | Guidance | NICE. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng116.

Pacella, M. L., Hruska, B., & Delahanty, D. L. (2013). The physical health consequences of PTSD and PTSD symptoms: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27(1), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.08.004.

Pietrzak, R. H., Goldstein, R. B., Southwick, S. M., & Grant, B. F. (2011). Prevalence and Axis I comorbidity of full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States: Results from Wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25(3), 456–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.11.010.

Pigeon, W., Allen, C., Possemato, K., Bergen-Cico, D., & Treatman, S. (2015). Feasibility and acceptability of a brief mindfulness program for veterans in primary care with posttraumatic stress disorder. Mindfulness, 6(5), 986–995. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0340-0.

Plummer, F., Manea, L., Trepel, D., & McMillan, D. (2016). Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: A systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 39, 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.11.005.

Possemato, K., Kuhn, E., Johnson, E., Hoffman, J. E., Owen, J. E., Kanuri, N., … Brooks, E. (2016). Using PTSD Coach in primary care with and without clinician support: A pilot randomized controlled trial. General Hospital Psychiatry, 38, 94–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.09.005.

Prins, A., Bovin, M. J., Smolenski, D. J., Marx, B. P., Kimerling, R., Jenkins-Guarnieri, M. A., … Tiet, Q. Q. (2016). The primary care PTSD screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5): Development and evaluation within a veteran primary care sample. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31(10), 1206–1211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3703-5.

Prins, A., Ouimette, P., Kimerling, R., Cameron, R. P., Hugelshofer, D. S., Shaw-Hegwer, J., … Sheikh, J. I. (2003). The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): Development and operating characteristics. Primary Care Psychiatry, 9(1), 9–14. https://doi.org/10.1185/135525703125002360.

Roberts, A. L., Gilman, S. E., Breslau, J., Breslau, N., & Koenen, K. C. (2011). Race/ethnic differences in exposure to traumatic events, development of post-traumatic stress disorder, and treatment-seeking for post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States. Psychological Medicine, 41(1), 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291710000401.

Rumpf, H.-J., Hapke, U., Meyer, C., & John, U. (2002). Screening for alcohol use disorders and at-risk drinking in the general population: Psychometric performance of three questionnaires. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 37(3), 261–268. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/37.3.261.

Rytwinski, N. K., Scur, M. D., Feeny, N. C., & Youngstrom, E. A. (2013). The co-occurrence of major depressive disorder among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26(3), 299–309. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21814.

Schnurr, P. P., Friedman, M. J., Oxman, T. E., Dietrich, A. J., Smith, M. W., Shiner, B., … Thurston, V. (2013). RESPECT-PTSD: Re-engineering systems for the primary care treatment of PTSD, A randomized controlled trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 28(1), 32–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2166-6.

Schnurr, P. P., & Lunney, C. A. (2016). Symptom change and quality of life in PTSD. Depression and Anxiety, 33(3), 247–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22477.

Spoont, M. R., Williams, J. W., Kehle-Forbes, S., Nieuwsma, J. A., Mann-Wrobel, M. C., & Gross, R. (2015). Does this patient have posttraumatic stress disorder? Rational clinical examination systematic review. JAMA, 314(5), 501–510. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.7877.

Taubman-Ben-Ari, O., Rabinowitz, J., Feldman, D., & Vaturi, R. (2001). Post-traumatic stress disorder in primary-care settings: Prevalence and physicians’ detection. Psychological Medicine, 31(3), 555–560.

van Minnen, A., Zoellner, L. A., Harned, M. S., & Mills, K. (2015). Changes in comorbid conditions after prolonged exposure for PTSD: A literature review. Current Psychiatry Reports, 17(3), 549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-015-0549-1.

Wald, J., & Taylor, S. (2009). Work impairment and disability in posttraumatic stress disorder: A review and recommendations for psychological injury research and practice. Psychological Injury and Law, 2(3), 254–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12207-009-9059-y.

Whooley, M. A., Avins, A. L., Miranda, J., & Browner, W. S. (1997). Case-finding instruments for depression. Two questions are as good as many. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 12(7), 439–445.

Zammit, S., Lewis, C., Dawson, S., Colley, H., McCann, H., Piekarski, A., … Bisson, J. (2018). Undetected post-traumatic stress disorder in secondary-care mental health services: Systematic review. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 212(1), 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2017.8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The original data collection was funded by a grant awarded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research. The production of current paper was not associated with any specific grant funding. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Research Involving Human Participants and/or Animals

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (NHS Health Research Authority, REC Reference: 16/WA/0055) and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

All participants provided inform consent for the statistical analyses and reporting of anonymous questionnaire data as reported in this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cowlishaw, S., Metcalf, O., Stone, C. et al. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Primary Care: A Study of General Practices in England. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 28, 427–435 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-020-09732-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-020-09732-6