Abstract

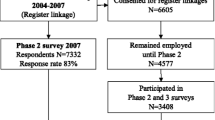

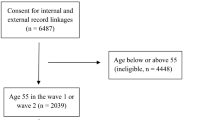

Purpose The aim of the present study was to estimate whether self-assessed mental well-being and work capacity determines future sickness absence (SA). Methods A questionnaire was sent to employed individuals (n = 6,140), aged 19–64 years, who were registered as sick-listed with a new sick-leave spell in 2008. The response rate was 54 %. In this study we included individuals with a single sick-leave spell in 2008 (n = 2,502). The WHO (Ten) Well-Being Index and four dimensions of self-assessed work capacity (knowledge, mental, collaborative, physical) were used as determinants. Future sickness absence was identified through national register in 2009. Outcome was defined as no sickness benefit compensated days (no SBCD) and at least one sickness benefit compensated day (SBCD). Logistic regression analyses were used to estimate odds ratios (OR) with 95 % confidence intervals (CI) for the likelihood of SBCD. Results In 2009, 28 % of the women and 22 % of the men had SBCD; the median was 59 and 66 benefit days, respectively. Individuals with low mental well-being had higher odds for SBCD with OR 1.29 (95 % CI 1.01–1.65) in the fully adjusted model. Participants reporting low work capacity in relation to knowledge (OR 1.55, 95 % CI 1.13–2.13), collaborative (OR 1.36, 95 % CI 1.03–1.79) and physical (OR 1.50, 95 % CI 1.22–1.86) demands at work had higher odds for SBCD after adjustments for all covariates; no relation was demonstrated with mental work capacity (OR 0.99, 95 % CI 0.76–1.27). Conclusion Mental well-being and work capacity emerged as determinants of future SA. Screening in health care could facilitate early identification of persons in need of interventions to prevent future SA.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Henderson M, Glozier N, Elliott KH. Long term sickness absence: is caused by common conditions and needs managing. BMJ Br Med J. 2005;330(7495):802–3.

OECD. Sickness, disability and work: breaking the barriers; a synthesis of findings across OECD countries. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2010.

Laaksonen M, He L, Pitkäniemi J. The durations of past sickness absences predict future absence episodes. J Occup Environ Med. 2013;55(1):87–92.

Roelen C, Koopmans P, Anema J, Van Der Beek A. Recurrence of medically certified sickness absence according to diagnosis: a sickness absence register study. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20(1):113–21.

Gjesdal S, Bratberg E. Diagnosis and duration of sickness absence as predictors for disability pension: results from a three-year, multi-register based and prospective study. Scand J Public Health. 2003;31(4):246–54.

Alexanderson K, Kivimäki M, Ferrie J, Westerlund H, Vahtera J, Singh-Manoux A, et al. Diagnosis-specific sick leave as a long-term predictor of disability pension: a 13-year follow-up of the GAZEL cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(2):155–9.

Lagerveld S, Bültmann U, Franche R, Van Dijk F, Vlasveld M, Van der Feltz-Cornelis C, et al. Factors associated with work participation and work functioning in depressed workers: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20(3):275–92.

Wilkie R, Pransky G. Improving work participation for adults with musculoskeletal conditions. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2012;26(5):733–42.

Sell L. Predicting long-term sickness absence and early retirement pension from self-reported work ability. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2009;82(9):1133–8.

Nystuen P, Hagen KB, Herrin J. Mental health problems as a cause of long-term sick leave in the Norwegian workforce. Scand J Public Health. 2001;29(3):175–82.

Ahola K, Virtanen M, Honkonen T, Isometsä E, Aromaa A, Lönnqvist J. Common mental disorders and subsequent work disability: a population-based Health 2000 Study. J Affect Disord. 2011;134:365–72.

Koopmans PC, Bültmann U, Roelen CA, Hoedeman R, van der Klink JJ, Groothoff JW. Recurrence of sickness absence due to common mental disorders. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2011;84(2):193–201.

Dewa CS, Lin E. Chronic physical illness, psychiatric disorder and disability in the workplace. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(1):41–50.

Plaisier I, Beekman ATF, de Graaf R, Smit JH, van Dyck R, Penninx BWJH. Work functioning in persons with depressive and anxiety disorders: the role of specific psychopathological characteristics. J Affect Disord. 2010;125(1–3):198–206.

Burton WN, Pransky G, Conti DJ, Chen C-Y, Edington DW. The association of medical conditions and presenteeism. J Occup Environ Med. 2004;46(Suppl):S38–45.

Collins JJ, Baase CM, Sharda CE, Ozminkowski RJ, Nicholson S, Billotti GM, et al. The assessment of chronic health conditions on work performance, absence, and total economic impact for employers. J Occup Environ Med. 2005;47(6):547–57.

Alexanderson K, Norlund A. Chapter 1. Aim, background, key concepts, regulations, and current statistics. Scand J Public Health Suppl. 2004;63:12–30.

Hensing G. Chapter 4. Methodological aspects in sickness-absence research. Scand J Public Health Suppl. 2004;63:44–48.

Thorsen SV, Burr H, Diderichsen F, Bjorner JB. A one-item workability measure mediates work demands, individual resources and health in the prediction of sickness absence. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2013;86(7):755–66.

Reiso H, Nygård JF, Brage S, Gulbrandsen P, Tellnes G. Work ability and duration of certified sickness absence. Scand J Public Health. 2001;29(3):218–25.

Wåhlin C, Ekberg K, Persson J, Bernfort L, Oberg B. Association between clinical and work-related interventions and return-to-work for patients with musculoskeletal or mental disorders. J Rehabil Med. 2012;44(4):355–62.

Vingård E, Lindberg P, Josephson M, Voss M, Heijbel B, Alfredsson L, et al. Long-term sick-listing among women in the public sector and its associations with age, social situation, lifestyle, and work factors: a three-year follow-up study. Scand J Public Health. 2005;33(5):370–5.

Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K. Depression and pain comorbidity: a literature review. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(20):2433–45.

Demyttenaere K, De Fruyt J, Stahl SM. The many faces of fatigue in major depressive disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;8(1):93–105.

Nierenberg AA, Keefe BR, Leslie VC, Alpert JE, Pava JA, Worthington JJ III, et al. Residual symptoms in depressed patients who respond acutely to fluoxetine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(4):221–5.

Hensing G, Spak F. Psychiatric disorders as a factor in sick-leave due to other diagnoses. A general population-based study. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172(3):250–6.

Kessler RC, Ormel J, Demler O, Stang PE. Comorbid mental disorders account for the role impairment of commonly occurring chronic physical disorders: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45(12):1257–66.

Brouwer S, Reneman MF, Bültmann U, van der Klink JJL, Groothoff JW. A prospective study of return to work across health conditions: perceived work attitude, self-efficacy and perceived social support. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20(1):104–12.

Holmgren K, Hensing G, Dellve L. The association between poor organizational climate and high work commitments, and sickness absence in a general population of women and men. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52(12):1179–85.

Love J, Holmgren K, Toren K, Hensing G. Can work ability explain the social gradient in sickness absence: a study of a general population in Sweden. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:163. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-163.

Högfeldt C. Fördröjning av sjukpenningsdata:en utvärdering av tremånadersregeln. Stockholm: Försäkringskassan; 2013 (in Swedish).

Försäkringskassan. Social Insurance in Figures 2009. Stockholm: Swedish Social Insurance Agency2009.

Bech P, Gudex C, Johansen KS. The WHO (Ten) well-being index: validation in diabetes. Psychother Psychosom. 1996;65(4):183–90.

Gustafsson K, Marklund S. Consequences of sickness presence and sickness absence on health and work ability: a Swedish prospective cohort study. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2011;24(2):1–13.

Hansson A, Hillerås P, Forsell Y. Well-being in an adult Swedish population. Soc Indic Res. 2005;74(2):313–25.

Love J, Andersson L, Moore CD, Hensing G. Psychometric analysis of the Swedish translation of the WHO well-being index. Qual Life Res. 2013;21(7):1249–53.

Forsell Y. Psychiatric symptoms, social disability, low wellbeing and need for treatment: data from a population-based study. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2004;50(3):195–203.

Wing JK, Babor T, Brugha T, Burke J, Cooper J, Giel R, et al. SCAN: schedules for clinical assessment in neuropsychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47(6):589–93.

Tuomi K, Oja G. Work ability index. Helsinki: Finnish Institute of Occupational Health; 1998.

Radkiewicz P, Widerszal-Bazyl M. Psychometric properties of work ability index in the light of comparative survey study. Int Congr Ser. 2005;1280:304–9.

Kristensen TS, Hannerz H, Hogh A, Borg V. The Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire-a tool for the assessment and improvement of the psychosocial work environment. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2005;31(6):438–49.

Holmgren K, Ivanoff SD. Women on sickness absence-views of possibilities and obstacles for returning to work. A focus group study. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26(4):213–22.

Savikko A, Alexanderson K, Hensing G. Do mental health problems increase sickness absence due to other diseases? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;36(6):310–6.

De Croon E. Studies in occupational epidemiology and the risk of overadjustment. Occup Environ Med. 2006;63(12):787.

Schisterman EF, Cole SR, Platt RW. Overadjustment bias and unnecessary adjustment in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology. 2009;20(4):488–95.

Schwarzer R, Jerusalem M. Self-efficacy measurement and generalized self-efficacy scale. In: Weinman J, Wright S, Johnston M, editors. Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal control beliefs. Windsor: Nfer-Nelson; 1995. p. 33–9.

Luszczynska A, Scholz U, Schwarzer R. The general self-efficacy scale: multicultural validation studies. J Psychol. 2005;139(5):439–57.

Löve J, Moore CD, Hensing G. Validation of the Swedish translation of the general self-efficacy scale. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(7):1249–53.

Thorslund M, Wärneryd B. Methodological research in the Swedish surveys of living conditions. Soc Indic Res. 1985;16(1):77–95.

Wikman A, Wärneryd B. Measurement errors in survey questions: explaining response variability. Soc Indic Res. 1990;22(2):199–212.

Krantz G, Östergren P-O. Women’s health: do common symptoms in women mirror general distress or specific disease entities? Scand J Public Health. 1999;27(4):311–7.

SCB. Folk- och bostadsräkningen 1985. Yrke och socioekonomisk indelning (SEI) [Population and housing Census 1985. Occupations and economic classification]. Stockholm: Statistics Sweden; 1989.

Bergman H, Källmén H. Alcohol use among Swedes and a psychometric evaluation of the alcohol use disorders identification test. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37(3):245–51.

Acuna E, Rodriguez C. The Treatment of Missing Values and its Effect on Classifier Accuracy. Classif Clust Data Min Appl. 2004:639–47.

DeNeve KM, Cooper H. The happy personality: a meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychol Bull. 1998;124(2):197–229.

Schonfeld WH, Verboncoeur CJ, Fifer SK, Lipschutz RC, Lubeck DP, Buesching DP. The functioning and well-being of patients with unrecognized anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 1997;43(2):105–19.

Rai D, Kosidou K, Lundberg M, Araya R, Lewis G, Magnusson C. Psychological distress and risk of long-term disability: population-based longitudinal study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(7):586–92.

Hensing G, Bertilsson M, Ahlborg G Jr, Waern M, Vaez M. Self-assessed mental health problems and work capacity as determinants of return to work: a prospective general population-based study of individuals with all-cause sickness absence. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1):259. doi:10.1186/1471-244x-13-259.

Soegaard HJ. Undetected common mental disorders in long-term sickness absence. Int J Family Med. 2012;2012:474989.

Rafanelli C, Park SK, Ruini C, Ottolini F, Cazzaro M, Fava GA. Rating well-being and distress. Stress Health. 2000;16(1):55–61.

Rai D, Skapinakis P, Wiles N, Lewis G, Araya R. Common mental disorders, subthreshold symptoms and disability: longitudinal study. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(5):411–2.

Gould R, Ilmarinen J, Jarvisalo J, Koskinen S. Dimensions of work ability. Results of the Health 2000 Survey. Dimensions of work ability. Results of the Health. Helsinki: Finnish Institute of Occupational Health; 2008.

Voss M, Floderus B, Diderichsen F. Physical, psychosocial, and organisational factors relative to sickness absence: a study based on Sweden Post. Occup Environ Med. 2001;58(3):178–84.

Gärtner FR, Nieuwenhuijsen K, van Dijk FJH, Sluiter JK. The impact of common mental disorders on the work functioning of nurses and allied health professionals: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(8):1047–61.

Danielsson M, Berlin M. Health in the working-age population Health in Sweden: the National Public Health Report 2012, Chapter 4. Scand J Public Health. 2012;40((9 suppl)):72–94.

Hoefsmit N, Houkes I, Nijhuis FJN. Intervention characteristics that facilitate return to work after sickness absence: a systematic literature review. J Occup Rehabil. 2012;22(4):462–77.

Arends I, Bruinvels DJ, Rebergen DS, Nieuwenhuijsen K, Madan I, Neumeyer-Gromen A, et al. Interventions to facilitate return to work in adults with adjustment disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD006389.

Nieuwenhuijsen K, Bültmann U, Neumeyer-Gromen A, Verhoeven AC, Verbeek JHAM, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM. Interventions to improve occupational health in depressed people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;16(2):CD006237.

Pomaki G, Franche R, Khushrushahi N, Murray E, Lampinen T, Mah P. Best practices for return-to-work/stay-at-work interventions for workers with mental health conditions. Vancouver, BC: Occupational Health and Safety Agency for Healthcare in BC (OHSAH); 2010.

Briand C, Durand MJ, St-Arnaud L, Corbière M. Work and mental health: learning from return-to-work rehabilitation programs designed for workers with musculoskeletal disorders. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2007;30(4–5):444–57.

Lederer V, Loisel P, Rivard M, Champagne F. Exploring the diversity of conceptualizations of work(dis)ability: a scoping review of published definitions. J Occup Rehabil. 2013. doi: 10.1007/s10926-013-9459-4.

Bertilsson M, Petersson E-L, Östlund G, Waern M, Hensing G. Capacity to work while depressed and anxious—a phenomenological study. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(20):1705–11.

Lacaille D, White MA, Backman CL, Gignac MAM. Problems faced at work due to inflammatory arthritis: new insights gained from understanding patients’ perspective. Arthritis Care Res. 2007;57(7):1269–79.

Michalak EE, Yatham LN, Maxwell V, Hale S, Lam RW. The impact of bipolar disorder upon work functioning: a qualitative analysis. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(1–2):126–43.

Ekberg K, Wåhlin C, Persson J, Bernfort L, Öberg B. Is mobility in the labor market a solution to sustainable return to work for some sick listed persons? J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21(3):355–65.

Möller HJ. Rating depressed patients: observer-vs self-assessment. Eur Psychiatry. 2000;15(3):160–72.

Conflict of interest

Monica Bertilsson declares that she has no conflict of interest. Marjan Vaez declares that she has no conflict of interest. Margda Waern declares that she has no conflict of interest. Gunnar Ahlborg Jr declares that he has no conflict of interest. Gunnel Hensing declares that she is a member of the scientific advisory committee of the Swedish Social Insurance Agency (unpaid expert consultancy).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bertilsson, M., Vaez, M., Waern, M. et al. A Prospective Study on Self-Assessed Mental Well-Being and Work Capacity as Determinants of All-Cause Sickness Absence. J Occup Rehabil 25, 52–64 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-014-9518-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-014-9518-5