Abstract

Science and technology parks (STPs) are non-spontaneous agglomerations aimed at encouraging the formation and growth of on-site technology and knowledge-based firms. STPs have diffused worldwide, attracting significant, and often public, investment. However, there are contrasting evidence and insights on the effectiveness of these local development, technology and innovation policy tools. This paper provides a comprehensive and systematic review of the STP literature (221 papers, 1987–2021), focusing especially on quantitative papers aimed at assessing the park effect on tenant’s performance. We perform an in-depth quantitative analyses, which allows us to go beyond the inconclusiveness reported in previous review papers, showing that the likelihood of finding positive STP effects increases considerably with sample size. We discuss the limitations of this literature and offer some suggestions for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Science and Technology Parks (STPs) have achieved near worldwide diffusion and have attracted the interest of both policymakers and the scientific community. STPs are non-spontaneous agglomerations whose management teams engage actively in encouraging the formation and growth of on-site technology and knowledge-based firms (Albahari et al., 2018).

Inspired by the success of famous spontaneous clusters, such as Silicon Valley and Route 128 (Appold, 2004), many national and regional governments have invested in STPs as technology and innovation policy tools. Examples include the governments of Japan (Bass, 1998), India (Biswas, 2004; Vaidyanathan, 2008), Taiwan (Hu et al., 2005; Xue, 1997), Brazil (Mello & Rocha, 2004), Russia (Kihlgren, 2003), Spain (Albahari et al., 2013), Italy (Landoni et al., 2010) and China (Watkins-Mathys & Foster, 2006), which have invested heavily in programmes to foster the creation of STPs. In other countries, such as the UK (Siegel et al., 2003b; Westhead & Storey, 1995), STPs are mainly university initiatives, which are exploited to facilitate the commercialisation of academic research (Markman et al., 2008; Storey & Tether, 1998) and ensure that the financial returns from technology transfer are internalised (Link et al., 2007).

Although complete statistics are not available, some numbers may help in understanding the importance of STPs. Over the past 15 years, SP activity worldwide has approximately doubled (Lecluyse et al., 2019), with over 400 STPs in Europe (Rowe, 2014) and 300 in North America (Battelle Technology Partnership Practice, 2013). Rodríguez-Pose and Hardy (2014) report more than 1500 STPs operating in China and India, and a great number of STPs in emerging economies in South America, Asia and Africa.

The interest of researchers and policymakers in STPs as technology and innovation policy instruments has grown in parallel with the increased diffusion worldwide of STPs.

In this paper, we provide a systematic review of the literature on the effects of STP location on tenant firms aimed at: (i) providing a critical summary of the existing research on STPs by focusing on quantitative works (ii) identifying the most frequent methodologies and their methodological shortcomings; (iii) summarising the main findings from research on STPs to inform policymakers and practitioners about the effects of STPs on tenants; (iv) performing a quantitative in-depth analysis to identify whether the findings from previous studies are sensitive to the samples and methodology used; (v) taking stock of previous work on STPs that explicitly takes into account the existence of heterogeneous effects both on a park- and firm-level and (vi) identifying trends and gaps in the literature and offering suggestions for further research.

Previous reviews of the literature on STPs (see Sect. 2) essentially coincides in indicating mixed results on almost all dimensions of the park effect on tenants. By performing an in-depth analysis of quantitative papers on the STP effect (see Sect. 4), we are able to make a substantial contribution to the knowledge of STPs by going beyond the inconclusiveness found in previous works. We observe that the probability of finding a positive and significant effect increases considerably with sample size. A complementary reason for the previous mixed evidence may be that most authors consider the average effect of the on-park location. We report evidence of the existence of heterogeneous effects according to both park and firm characteristics (see Sect. 5).

The wide and fragmented literature on STPs has recently motivated other review efforts (e.g.,Diez-Vial & Montoro-Sanchez, 2017; Henriques et al., 2018b; Hobbs et al., 2017a; Lecluyse et al., 2019; Link & Scott, 2007; Mora-Valentín et al., 2018). In Sect. 2, we review these efforts and explain why and how our study contributes to this literature. In Sect. 3, we describe the methodology and provide a general review of the literature on STPs. Section 4 delves into quantitative papers whose aim is to analyse STPs effects on tenant firms. In Sect. 5, we take stock of the works that explicitly considers heterogeneous effects of the on-park location. Section 6 concludes and provides some directions for further research.

2 Contributions of our review

The first review, to our knowledge, is Link and Scott (2007). They review the origins of STPs, and the theory and rationality behind them. In addition, they offer a review of the (few) empirical studies on STPs at that time and conclude that one key challenge in the literature should be to quantify STP impact.

Diez-Vial and Montoro-Sanchez (2017) review the literature of STPs (1996–2015) from a bibliometric point of view using co-citation analysis and bibliographic coupling with the aim to identify the foundations of parks and incubation research. They focus on 222 citing documents and 459 cited references and identify four periods: (i) the emergence period (1996–2000), characterized by a clear separation between the analysis of parks and incubators, (ii) the growth period (2001–2005), focusing on high tech industries and the role played by universities, (iii) the opening period (2006–2010), characterized by the interest on STP performance, incubators best practices and the effectiveness of university-technology transfer and (iv) the consolidation period (2011–2015), focusing on the supporting role of incubators (and to a lesser extent parks) on new companies development processes and on the study on how certain location, mainly parks, can improve local innovation. Overall, they conclude that the analysis of parks has been approached from different (complementary) theoretical perspectives like economic geography, entrepreneurship, networks or the management literature.

A closely related contribution is Mora-Valentín et al. (2018). They also review the literature of STPs (1996–2017) from a bibliometric point of view, but they use co-wording rather than co-citation analysis. They identify 447 works and provide a descriptive analysis identifying the more prolific authors in the field, as well as the journals that account for more publications. The co-word analysis identifies five main themes: innovation, park, inter-organisational relationship, spillover and technology. For the 2008–2012 period, the literature focuses on innovation, inter-organisational relationships, technology transfer, performance and growth or management. From 2012 onwards, some of these topics, such as inter-organisational relationships and performance and growth are further developed and other, such as innovation policies, entrepreneurship and human resource management and business models in STPs have emerged.

Hobbs et al. (2017a) provide an annotated and analytical literature review. They identify 87 contributions until 2016, concluding that the academic attention to STPs has increased, but not exploded and consider that it was still in an embryonic stage. They highlight that the scope of the literature is global, although about one third of the studies focus on China or the United Kingdom.

Henriques et al. (2018) review 56 papers (1980–2016). Their major contribution is to indicate five gaps in the literature: (i) the scarcity of studies in emerging economies, (ii) the absence of studies empirically comparing STPs in emerging vs mature economies, (iii) the scarcity of studies outside Europe and Asia, (iv) the absence of studies comparing STPs in different countries and (v) the reasons why some studies find that STPs perform lower than expected. They wonder if the expectations on STPs are too high and highlight that studies should be carried out to understand the drivers of the impact or lack of impact.

In our view, the paper more closely related to our work is Lecluyse et al. (2019). They review 175 STP papers (1988–2017) using a broad approach, which is built on an Input-Mediator-Outcome framework and distinguishes between the regional level, the SP level and the firm level. Their main conclusion is that results are highly inconclusive. To enable the advancement of knowledge they propose topics and levels of analysis, which may allow gaining in-depth insights into when, how and why STPs provide value-added contributions.Footnote 1

Compared with previous reviews, the main contributions of our paper can be summarized as follows.

First, we review papers until 2021 (included). In the four additional years we cover with respect to the most recent previous review published, a large number of relevant papers has been published. Out of the 221 papers we review (see Sect. 3.1), 59 papers (27% of our sample) have been published in the years 2018–2021.

Second, although we review all the papers dealing with STPs, which allows us to identify the main topics analysed in the literature (see Sect. 3.3), we narrow the focus of our review to studies analysing park effect on tenant’s performance.

Third, due to this narrower scope of our review, we can adopt a different approach, applying quantitative methods to carry out an in-depth analysis of these papers on different types of effects; in this way, we are able to go beyond the inconclusiveness highlighted in previous review papers, and highlight the main messages from previous works.

Fourth, following the recommendations from previous reviews (Henriques et al., 2018; Lecluyse et al., 2019), we explicitly consider the heterogeneous nature of STPs to extract new conclusions compared with previous review papers.

Overall, our focus on the results of previous works and the methodology followed to analyse these results, allows us to integrate knowledge from previous studies and to build evidence on the effect of the on-park location on tenants performance.

3 A general review of STPs literature

In this section, we describe the methodology followed to select papers to review, provide some basic bibliometric indicators and identify papers’ main topics and aims.

3.1 Methodology

This paper is based on an in-depth literature review and a systematic search methodology to ensure the inclusion of all relevant contributions and facilitate future updating. We identified the papers using a keyword search in Web of Knowledge databases (currently managed by Clarivate Analytics). To narrow our search to identify the most relevant papers, we limited the Databases, Document Types and Research Areas to those shown in Table 1.

The second step of our methodology was to identify research scope in terms of the organisations studied. There are several definitions of STP,Footnote 2 due, likely, to the variety of existing experiences, which has resulted in different interpretations of the STP concept. Some authors consider it ‘nebulous’ (Shearmur & Doloreux, 2000) and highlight the lack of agreement over their definition, which has been exacerbated by the many different terms used in the literature to describe parks,Footnote 3 for example, science park, research park, technology park, science and technology park, business park, innovation centre, technopole, etc. (Chan & Lau, 2005; Link & Scott, 2007; Shearmur & Doloreux, 2000; Sofouli & Vonortas, 2007). To add to this confusion, the terms ‘STP’ and ‘incubator’ are often used interchangeably, despite the different aims and distinctive characteristics of these entities.Footnote 4

Therefore, in the Topic field of the web platform, we employed a set of keywords, which we broadened successively as new papers were analysed. Table 2 presents the keywords used and the numbers of papers identified by each keyword.

Our keyword search, performed on the 8th January 2022, identified 1188 papers. This number included some duplicates resulting from the use of similar keywords. After purging our sample of duplicate entries (using Endnote Web, a Clarivate Analytics product), we obtained 965 papers. From this total, we rejected 744 following a reading of their abstracts.

In the next step, we considered both backward (papers cited by the selected papers) and forward (papers citing the selected papers) citations, to ensure the inclusion of all relevant papers. In the final step, we conducted a manual selection of the relevant papers. At the end of this process, we obtained 221 papers considered relevant for our review.

3.2 Description of the studies

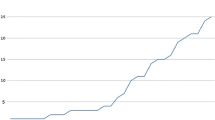

Figures 1 and 2 depict the distribution of the 221 papers by publication year and journal. We can observe that the scholarly interest in STPs shows no sign of waning, with one third of the papers included in our review published in the last 5 years (2017–2021). Two journals, namely The Journal of Technology Transfer (JoTT) and Technovation, are the most cited, accounting for the 20% of all the works reviewed. It is worth noting that, while Technovation was clearly the main outlet before 2016, JoTT has assumed a leading position in recent years, with 10 papers published in the last 5 years.

Figure 3 shows numbers of papers by STP location; the main focus is on STPs in China, Spain, Taiwan, Sweden, the USA and the UK, although most of the industrialised countries are covered. There is also evidence on STPs in emerging economies (25% of our sample), although more studies on developing countries are needed, as suggested by Henriques et al. (2018).

Figure 4 depicts the most common keywords listed in the selected papers. It gives an idea of the complexity and interdisciplinary nature of the research on STPs. These keywords include, among others, terms related to innovation, knowledge transfer, university-industry relations, geography, regional development, triple helix and entrepreneurship.

3.3 Main topics analysed

We can identify six broad categories of aims: (i) project hypothesis for setting up a new STP or a group of STPs; (ii) STPs performance assessment framework; (iii) evolution paths and outcomes of an STP or a group of STPs; (iv) best practices and critical success factors; (v) role of STPs in national/regional economy; (vi) effects on tenant firms.

First, some studies hypothesise about the setting up of new parks or a group of parks in Kuwait (Al-Sultan, 1998) the Rome area (Cricelli et al., 1997), Shanghai (Ma, 1998) and Ankara University STP (Fikirkoca & Saritas, 2012) in a bid to ensure their successful establishment.

Second, although the design of an assessment framework for STPs is particularly difficult due, in part, to the multiple stakeholders and their various and, sometimes, conflicting interests, some papers make some attempts in this direction (Chan & Lau, 2005; Ferrara et al., 2016; Guadix et al., 2016; Hobbs et al., 2020; Jimenez-Zarco et al., 2013; Latorre et al., 2017; Meseguer-Martinez et al., 2021; Ribeiro et al., 2021; Xia et al., 2017; Zeng et al., 2010).

Third, several papers provide information on the results and development dynamics of an individual STP (e.g. Barbera & Fassero, 2013; Chou & Lin, 2007; Hommen et al., 2006; Howard & Link, 2019; Hu, 2011; Ku et al., 2005; Kulke, 2008; Lee & Yang, 2000; Miao & Hall, 2014; Phillips & Yeung, 2003; Yan et al., 2020; Zou & Zhao, 2014) or a group of STPs (Bakouros et al., 2002; Chordà, 1996; Eto, 2005; Kim & Jung, 2010; Scott, 1990; Sofouli & Vonortas, 2007; Suzuki, 2004; Yang, Hsu, et al., 2009; Yang, Motohashi, et al., 2009) in a territory, region or country. The importance is acknowledged of the historical and cultural contexts of these innovation intensive environments (Roberts, 2005), and some papers focus on the historical and contextual evolutions of STPs (Feldman, 2007; Kim et al., 2014; Mathews, 1997; Park, 2004; Shin, 2001; Zhou, 2005) and compare STPs in different countries (Bruton, 1998; Garnsey & Longhi, 2004; Gašparíková, 1998; Huang & Fernández-Maldonado, 2016). With few exceptions (e.g. Brooker, 2013; Lewis & Tenzer, 1992), most of the cases analysed are successful cases.

Fourth, the interest of policy-makers and industry leaders in identifying best practice in the formation and operation of STPs has increased and several papers focus on individual examples of best practice (e.g. Giaretta, 2014; Tan, 2006; Zhu & Tann, 2005) and the transfer of best practice from one context to another (Wonglimpiyarat, 2010). Other authors identify more directly the critical success factors for STPs (Berbegal-Mirabent et al., 2020; Cabral, 1998;Footnote 5 Etzkowitz & Zhou, 2018; Khanmirzaee et al., 2021; Koh et al., 2005; Xie et al., 2018; Yang, 2018) or focus on STP business model and strategy (Bozzo, 1998; Durão et al., 2005; Hansson et al., 2005). Some recent papers emphasise best management practices (Al-Kfairy & Mellor, 2020; Durak et al., 2021; Laspia et al., 2021; Magalhães Correia et al., 2021) and the role played by tenant expectations and how STPs can modulate them (Lecluyse & Knockaert, 2020; Ng et al., 2021).

Fifth, many papers investigate the role played by STPs in the national and/or regional economy, focusing on several aspects. These includes the role of STPs in fostering indigenous innovation capacities strategy and increasing regional technology growth and competitiveness (Olcay & Bulu, 2016; Zeng et al., 2011; Zhang & Wu, 2012), in encouraging technological entrepreneurship (Yu et al., 2009), in playing a bridging role and facilitating knowledge transfer among various actors (Albahari et al., 2019; Balle et al., 2019; Benneworth & Ratinho, 2014; Link & Scott, 2007; Meseguer-Martinez et al., 2020; Steruska et al., 2019; Walcott, 2002; Wicaksono & Ririh, 2021), especially with universities (Aportela-Rodriguez & Pacios, 2017; Gan et al., 2021; Löfsten et al., 2020; Phongthiya et al., 2021), in fostering open innovation (Silva et al., 2020), in modernizing a country’s economy and innovation system (Chen et al., 2013; Phelps & Dawood, 2014) and in financing technology (Scandizzo, 2005). When debating the effect of STPs in regional economies, particularly interesting is the case of structurally underdeveloped (del Castillo Hermosa & Barroeta, 1998; Grasland, 1992) and rural (Goldstein & Luger, 1992) regions.

Sixth, the main reason for the existence and proliferation of STPs and for the amount of public investment in STPs are the supposed benefits for tenant firms. Due to the importance of this topic for assessing the effectiveness of STPs, and the large number of papers dealing with this issue, in what follows we focus our attention on research which uses tenants as the unit of analysis, and, due to the idiosyncrasy of the research questions, we focus mainly on papers that use quantitative methods.

4 Analysis of quantitative studies focusing on STP effect on tenant firms

In this section, we analyse in depth quantitative papers dealing with the estimation of the effects of the on-park location on tenant firms. In the first subsection, we provide a description of the sample used and the main methodologies applied, then in Sect. 4.2. we report the effect found on three main dimensions: economic performance, innovation performance and cooperation patterns. Section 4.3. presents the results of a regression analysis, done to identify whether the effects found are sensitive to the samples and methodologies used.

4.1 Samples and methods

Table 10 (Annex 2) provides a list of the quantitative papers included in the analysis. We observe that they include a large variety of samples and methodologies. However, it is possible to make some general comments. Many of the samples are based on comparing groups of on-park firms to comparable groups of off-park firms, to assess whether their results differ. The comparability criteria are usually based on several firms’ characteristics (such as firm age, size, industry sector, innovation effort, etc.). Others compare the (within) performance of firms during location in an STP against either after leaving the park or before joining it,Footnote 6 while some other studies no do not employ any comparability criteria.

It can be seen that, with some notable exceptions, most studies rely on small park and firm samples (see Annex 2). Also, regression analysis tends to be the preferred methodology if larger datasets are available, but mean comparisons between on- and off-park samples are also frequent.

An important limitation of many of these studies and one that many researchers ignore, is the selection bias problem. That is, that firms located in an STP may, a priori, be different from off-park firms due to unobserved factors. Failing to address these sources of endogeneity can result in biased results. For example, in an assessment of whether on-park firms collaborate more with academia compared to off-park firms, it might be that the on-park firms have a stronger taste for science (which would emerge even were they located outside an STP). Ignoring this source of unobserved heterogeneity in the analysis could result in the finding that on-park firms collaborate more with academia, which, in turn, would be considered the result of on-park location. Few studies, mostly recently (e.g. Hasan et al., 2020; Koster et al., 2019; Liberati et al., 2016; Ramírez-Alesón & Fernández-Olmos, 2018; Siegel et al., 2003a; Squicciarini, 2008; Ubeda et al., 2019; Vásquez-Urriago et al., 2014, 2016a; Xue & Zhao, 2021; Yang, Hsu, et al., 2009; Yang, Motohashi, et al., 2009), apply econometric methods to address the selection bias problem.

4.2 Type of effects analysed

Papers aimed at assessing the impact of on-park location on tenants focus mainly on three main dimensions (Fig. 5): firm’s economic performance, tenants’ innovation and firm’s patterns of cooperation, especially with universities and other research centres.

4.2.1 Economic performance

Table 3 presents the most frequent variables used to assess the impacts of STPs on the economic performance of park firms. A few papers deal with the effects of STPs on firms’ economic performance. The main indicators are employment and sales growth, productivity and profitability. In relation to employment, Löfsten and Lindelöf (2001, 2002, 2003) find that on-park firms show substantially higher rates of job creation than firms in the off-park sample. This result is confirmed by Colombo and Delmastro (2002), Díez-Vial and Fernández-Olmos (2017a)Footnote 7 and Koster et al. (2019). However, Ferguson, (2004) argues that STPs can have positive effects on the employment growth of tenant firms only up to a certain point, while on-park location is a limiting factor for firms entering a development period characterised by high-growth. This latter result is refuted by Arauzo-Carod et al. (2018); while finding a negative average effect on employment growth and sales growth, they show that STPs are more beneficial for high-growth firms (see Sect. 5). Additionally, Cumming et al. (2019) find parks have a positive impact on start-ups survival rate.

The three papers by Löfsten & Lindelöf also find that on-park firms record substantially higher sales growth compared to the off-park sample and this finding is confirmed by Liberati et al. (2016) and Díez-Vial and Fernández-Olmos (2017a). However, Lamperti et al. (2017) find no statistically significant differences between on- and off-park samples.

Sung et al. (2003) and Fernández-Alles et al. (2015), from a more qualitative perspective, report on-park managers’ opinions on the effect of the on-park location on firm growth. Sung et al. find that STPs have a very small influence on firm growth, but Fernández-Alles et al. conclude that STPs are perceived by Academic Spin-Off (ASO) managers to be important for the initial establishment of an ASO, but becomes redundant as the firm achieves maturity.

In relation to productivity, Hu (2007) finds that Chinese STPs do not help firms to achieve higher labour productivity growth, and Zhang and Sonobe (2011) suggest that this result can be explained by congestion effects in STPs that likely outweigh the positive effects of agglomeration economies in relation to labour productivity. The recent papers by Hasan et al. (2020) and Koster et al. (2019) find a positive effect of STPs on global firm productivity. Koster et al. (2019) also show employees of on-park firms have higher wages.

Finally, In the case of profitability, there is no clear evidence of better performance of on-park firms (Liberati et al., 2016; Lindelöf & Löfsten, 2002, 2003; Löfsten & Lindelöf, 2001, 2002).

4.2.2 Innovation performance

Evaluation of the on-park effect on firms’ innovative performance has attracted the attention of several researchers, suggesting that STPs have an impact on innovation performance. However, again, the empirical evidence is contrasting over all the dimensions considered, which deal with the park effect on innovation inputs (R&D intensity and workforce quality), outputs (patenting activity and new product development and sales), and R&D productivity.

Table 4 presents the most frequent variables used to assess innovation performance and the sign of the effect found.

4.2.2.1 Inputs

In the case of the inputs to the innovation process, Fukugawa (2006), Yang, Motohashi, et al. (2009), Yang, Hsu, et al. (2009), Díez-Vial and Fernández-Olmos (2015), Lamperti et al. (2017) and Xue and Zhao (2021) show that on-park firms are more R&D intensive than off-park firms, while Westhead (1997) and Colombo and Delmastro (2002) do not find a positive correlation between on-park location and R&D intensity. There is also contrasting evidence related to workforce quality (measured as the percentage of researchers and engineers in the total workforce) (see Table 4).

4.2.2.2 Outputs

Studies that consider the outputs of the innovation process focus mainly on assessing the park effect on patents, new product development and innovation sales. A positive impact on the number of patents filed has been found by Squicciarini (2008), Huang et al., (2012), Lamperti et al., (2017) and Corrocher et al. (2019).Footnote 8 Corrocher et al. (2019) also find that STP location increases the likelihood of patenting. Other authors (Chan et al., 2011; Colombo & Delmastro, 2002; Liberati et al., 2016; Lindelöf & Löfsten, 2002, 2003; Löfsten & Lindelöf, 2002; Squicciarini, 2009; Westhead, 1997) find no statistically significant differences between on- and off-park firms. In the case of new product development and sales, some studies find a positive effect (Chan et al., 2011; Claver-Cortés et al., 2018; Díez-Vial & Fernández-Olmos, 2015; Siegel et al., 2003a; Ubeda et al., 2019; Vásquez-Urriago et al., 2014, 2016b), while others report non-significant effects (Felsenstein, 1994; Lindelöf & Löfsten, 2002, 2003; Löfsten & Lindelöf, 2002; Radosevic & Myrzakhmet, 2009; Ramírez-Alesón & Fernández-Olmos, 2018; Westhead, 1997). Montoro-Sánchez et al. (2011) find that knowledge spillovers have a stronger effect on innovation and R&D cooperation in the case of on-park firms.

4.2.2.3 R&D productivity

Finally, some papers assess the effect of on-park location on R&D productivity, taken account of both the inputs to and outputs of the innovation process. Siegel et al. (2003b) define an R&D production function with three possible R&D outputs (number of new products/services launched; number of patents applied for or awarded, and number of copyrights granted) and two R&D inputs (R&D expenditure and number of scientists and engineers). They find that on-park firms achieve slightly higher research productivity than the equivalent off-park sample. This finding is confirmed by Yang, Motohashi, et al. (2009), Yang, Hsu, et al. (2009), but is rejected by Westhead (1997).

4.2.3 Cooperation patterns

Various researchers evaluate the park effect on the cooperation patterns of tenant firms, with both other on-park and with off-park organisations, especially with universities.Footnote 9

The proximity that an on park location provides to other on park firms is part of the added value provided to tenants, since it can facilitate interaction among firms. However, studies that analyse this issue explicitly (Chan et al., 2010; Radosevic & Myrzakhmet, 2009) find that on-park firms are more likely to collaborate with off-park firms than with other park firms. Vásquez-Urriago et al. (2016a) show that on-park location increases the likelihood of cooperation and increases the intangible benefits of cooperation.Footnote 10

A common objective among all STPs is fostering knowledge and technology transfer between universities and industry (Link & Scott, 2006; Storey & Tether, 1998). The type and extent of the interactions between tenant firms and universities or public research centres has been widely investigated with inconclusive results (Table 5).

Some studies find a non-significant effect of on-park location on the establishment of links between firms and universities. Quintas et al. (1992) suggest that the extent of the research links between academic institutions and STP firms appears to differ very little from the links to academia of similar firms located outside a park. This result is confirmed by Malairaja and Zawdie (2008), who demonstrate that the level of interaction between firms and universities generally is robust, but that there are no statistically significant differences between on- and off-park firms. Somewhat surprisingly, Radosevic and Myrzakhmet (2009) find that the propensity to establish links with universities is stronger in the off-park sample.

Other authors find a positive effect of on-park location on the patterns of collaboration with universities. Felsenstein (1994) shows that the level of interaction between on park firms and local universities is generally low, but is higher than the levels of interaction between off park companies and universities. Vedovello (1997) concludes that STPs facilitate the establishment of informal links, but have no influence on firms’ capacities to establish formal links to universities. Phillimore (1999) suggests that consideration should be given to both formal and informal collaboration when evaluating the effects of STPs on the propensity to cooperate. However, there is also some evidence that on-park firms show a higher propensity to establish formal links and engage in joint research with research institutes (Colombo & Delmastro, 2002; Díez-Vial & Fernández-Olmos, 2015; Fukugawa, 2006; Löfsten & Lindelöf, 2002, 2003; Minguillo et al., 2015). Caldera and Debande (2010), adopting a university perspective, determine that universities with STPs generate more R&D income.Footnote 11

A possible explanation for these contrasting findings is that, in some cases, managers may choose to locate on-park to obtain prestige and image of such a location, obtain access to university facilities and benefit from prestige endowed by a link to a university (Phillips & Yeung, 2003; Westhead & Batstone, 1998). None of these reasons indicate the need for a formal link between the firm and a university. On the other hand, there is a stream of literature that analyses the importance for parks and their tenants to be geographically close to a university. Link and Scott (2003) find a direct relationship between geographical proximity between the park and a university, and the park’s employment growth. In the case of a formal relationship between park and university, university managers expect enhanced research output (e.g., publications and patents) and increased extramural funding. Geographical proximity to a university also has a positive effect on the proportion of university spin-offs in the park (Link & Scott, 2005). In fact, STPs seem to be particularly important for the creation of ASOs (Lindelöf & Löfsten, 2005), which might explain why on-park firms’ managers seem to give more importance to geographical proximity to a university than managers of off-park-firms (Dettwiler et al., 2006).

4.3 Regression analysis

The previous section shows that clear conclusions about the effect of STPs on firms are difficult to draw. For almost every dependent variable, we can find studies that show a positive effect and studies that find no significant effect of STPs on firms. These mixed results has been highlighted by other literature reviews (e.g., Hobbs et al., 2017a; Lecluyse et al., 2019).

In this section, we want to analyse if these mixed results can be explained by methodological differences across studies and by the different contextual factors of the analysis.

On the one hand, one potential explanatory factor for the mixed results is the sample size. We expect that papers that use larger samples are more likely to achieve a positive and significant STP effect. The reason is that statistical significance crucially depends on sample size (ceteris paribus, smaller samples result in larger standard errors, which, in turn, lead to larger p-values and, accordingly, less statistical significance).

On the other hand, we expect that papers using just mean comparisons between on- and off-park firms are more likely to yield a positive STP effect. This is due to the endogeneity of STP location. Firms that decide to locate on-park must pass the scrutiny of the park’s management, whose admission criteria are based mostly on the viability of the business idea and the firm’s growth potential. Thus, we can expect on-park firms to be, at least to some extent, ‘better’ than off-park firms so that the simple comparison will overestimate the STP effect. One way to address this situation is to control for firm characteristics, such as size, R&D intensity or industry, (that is, using ‘conditional mean differences’). However, it may well be that on-park firms may be different from off-park firms in some unobserved characteristics. If this is the case, the differences in the conditional means would also overestimate the STP effect and other methods such as instrumental variables or differences in differences should be used to get consistent estimates of the STP effect.

In this section, we conduct a statistical analysis of the quantitative studies of STP impact on tenants. We identified 38 studies dealing with this topic, with 148 estimations of STP impact on any tenant output. Of these 148 observations, 92 (62.16%) yield a (statistically significant) positive effect of STPs with 56 (37.84%) showing no (statistically significant) positive effect.Footnote 12

The objective of this statistical analysis is to analyse whether there are systematic relationships between the results of the studies and their characteristics. More precisely, we will consider four characteristics: sample size, statistical method, time period and geographical area.

First, we define sample size as the logarithm of the number of firms located on park in the study (lsampleon). The median study uses only 134 on-park firms, with some studies using a large number of firms which results in a mean value of 326.8 on-park firms.

Second, we define three dummy variables according to the methodology used: meandiff, which takes the value of 1 for those analyses reporting unconditional mean differences between tenants and firms outside parks (14 estimates, 9.46%), cmeandiff, which takes the value of 1 for those reporting conditional mean differences, because they use either multiple regression models or matching procedures (104 estimates, 70.27%) and endog which takes the value of 1 for those that use some other method to address endogeneity such as instrumental variables or differences in differences (30 estimates, 20.27% of estimates).

Third, we are also interested in analysing whether the STP effect shows some kind of trend. To do this, we defined a dummy variable (old) to identify studies based on pre-2005 data. This cut-off point was chosen because it results in samples of almost equal size (45.3% estimates using pre-2005 data and 54.7% estimates using post-2005 data).

Fourth, we define three dummy variables for the countries more represented in our sample: spain which takes the value of 1 for those analysis using Spanish data (39 estimates, 26.35%), italy, which takes the value of 1 for those analysis using Italian data (29 estimates, 19.6%) and sweden, which takes the value of 1 for those analysis using Swedish data (28 estimates, 18.9%).

Table 6 presents the results of this analysis. We employ a probit model and report marginal effects at the mean. Columns (1) and (2) focus only on the technical characteristics of the studies (sample and methodology) and Columns (3) and (4) include also the time period and the countries. Columns (1) and (3) report robust standard errors and Columns (2) and (4) report standard errors clustered by paper.

First, we observe that, as expected, the sample size is positively correlated to the likelihood of a (positive and statistically significant) effect of STPs. This result is very significant from a statistical point of view. We can see in Fig. 6 that the probability of finding a positive and significant STP effect increases very fast with sample size. It should be noted that with samples larger than 350 STPs firms the likelihood of finding a positive and significant STP impact is above 70% and with samples larger than 800 firms is above 80%. However, with samples lower than 50 on-park firms the likelihood of finding a positive and significant STP effect is below 50%. The main reason for that is the statistical significance depends on the ratio between the estimated coefficient (usually positive) and the estimated standard deviation for that coefficient (the standard error). That is, statistical significance inversely depends on the sample size. It should be highlighted that most of the reviewed studies deal with very small sample sizes of STP firms (only 20% of analyses deal with samples larger than 500 on-park firms). The fact that small sample size reduces statistical power (the ability to detect effects that actually exist in the population) is well known in statistics and seems to be the main driver behind the contradictory evidence on STP effect.

Second, regarding the effect of the method employed, we observe that, on the one hand, studies using unconditional mean differences show a positive non-significant coefficient (the reference group is studies based on conditional mean differences), supporting the idea that, to some extent, these results may reflect the self-selection of better firms into STPs. However, if this self-selection is addressed with more adequate methods, the coefficient remains positive and non-significant (again, compared to the reference group of studies using conditional mean differences). At first sight, these results seem striking. However, a closer examination of analyses using conditional mean differences (usually employing multiple regression models) shows that they often employ the types of covariates that are considered ‘bad controls’ (Wooldridge, 2005) because they are also potential channels for STP effects. For example, if STPs are able to increase the R&D intensity (or cooperation activities) of tenants, and R&D intensity (or cooperation activities) influence the output measure (such as productivity or sales from new products), then holding R&D intensity (or cooperation activities) constant when estimating the STP effect will result in the STP effect being underestimated. This applies to most studies that employ multiple regression models.

Third, we find that the age of the study has a small, positive and non-significant coefficient, suggesting that the STP impact has not substantially varied over time.

Fourth, we do not find statistical evidence of inter-country differences in the STP effect. The coefficients for Spain and Italy are positive but non-significant while the coefficient for Sweden is negative but also non-significant.

So far, our analysis has employed a broad definition of STP output. In what follows, we adopt a stricter definition, which excludes indicators that, actually, are inputs for firms (e.g., R&D investment or cooperation with universities). This provides a sample of 109 observations, of which 64 (58.7%) show a (statistically significant) positive effect of STPs and 45 (41.3%) do not.

Table 7 (which is organised similar to Table 6) presents the results of the analysis, which are similar to those described above. That is, our results are not dependent on a broader or narrower definition of output.

5 Heterogeneous effects

In the previous sections, we reported evidence of the average effects of on-park location. However, the effects of on-park location may differ for firms with different characteristics and, in addition, some park characteristics are more likely to provide tenant firms with added value. Authors that consider only average effects, ignore the possibility of heterogeneous effects, which may be one of the reasons behind the mixed evidence in the literature, as suggested by Albahari (2015, 2019). In this section, following the suggestions of Henriques et al (2018) and Lecluyse et al., 2019), we review papers explicitly considering firm- and park- characteristics when assessing the impact of the on-park location on tenants.

Tables 8 and 9 include quantitative papers that take account of park and tenant characteristics respectively, and their main findings. It can be seen that, both park and tenant characteristics might be affecting the added-value to firms of on-park location. This supports the hypothesis that some parks are more effective and that some firms benefit more from being located in an STP.

5.1 Park characteristics

In the case of park-level heterogeneity, park age is a frequently considered variable. It has been found to have a positive effect on sales (Liberati et al., 2016), R&D efficiency (Yang & Lee, 2021) and number of university spin-offs within the park (Link & Scott, 2005). Its effect on patents is not clear, with both positive (Teng et al., 2020) and negative (Squicciarini, 2009) effects found. Albahari et al. (2018) show park age has a non-linear effect on tenants’ innovation performance, with firms in younger and older parks outperforming firms in medium-aged parks. Lamperti et al. (2017) find a positive, but not statistically significant effect of park age on patenting activity of firms and a negative (non-significant) effect on tenants’ propensity to invest in R&D.

There is consensus in the literature about the importance of links to renowned and dynamic research universities (Bigliardi et al., 2006; Cabral, 1998; Harper & Georghiou, 2005; Ramasamy et al., 2004; Ratinho & Henriques, 2010; Yang, 2018), and access to diverse and talented human resources (Cabral, 1998; Harper & Georghiou, 2005; Koh et al., 2005; Löfsten et al., 2020; Ramasamy et al., 2004). The level of involvement of universities in the park is considered explicitly in some quantitative studies. Yang and Lee (2021) find parks with closer R&D collaborations with HEIs have greater R&D efficiency. Albahari et al. (2017) found a positive effect on tenants’ patenting activity, but a negative effect on innovation sales, while Teng et al. (2020) show a negative effect on both number of patents, in line with Squicciarini (2009), and on innovation sales. Arauzo-Carod et al. (2018) show a positive effect on sales and employment growth, while Link and Scott (2005) found no significant effects on the number of university spin-offs companies created, although they show that a greater geographical distance from a university has a negative effect. The number of universities linked to the park has a positive effect on tenants’ patenting activity and a not statistically significant effect on tenants’ propensity to invest in R&D (Lamperti et al., 2017).

Park size has been shown to have a positive effect on firms’ innovation sales (Albahari et al., 2018), patenting activity (Squicciarini, 2009) and R&D efficiency (Yang & Lee, 2021). Cadorin et al. (2021) find that park size has a positive impact on a composite indicator of the success of tenants.

The level of specialization of STPs affects positively the propensity to cooperate with other tenants (Koçak & Can, 2014), invest in R&D (Lamperti et al., 2017) and sales growth (Gwebu et al., 2019),Footnote 13 although Liberati et al. (2016) found a negative effect of degree of park specialization on tenants’ sales.

The characteristics of the region in which the parks are located influence the park effect (Poonjan et al., 2020). Albahari et al. (2018) show that firms in less technologically developed regions benefit more from being on-park.

Other park characteristics that have been shown to modulate the park effect are number of research centres (Lamperti et al., 2017), presence of very large companies (outliers) (Squicciarini, 2009), park ownership type (public/private) (Liberati et al., 2016), the quality of human capital (Yang & Lee, 2021), the number of co-located firms that share related and complementary business activities (Gwebu et al., 2019), and management company size (Albahari et al., 2018).

5.2 Firm characteristics

When firm-level heterogeneity is considered, authors consider the possibility that some firms benefit more than others from being located on-park. Tenants’ size is one of the most studied variables. Park location seems more beneficial for small firms in terms of sales (Liberati et al., 2016), patenting activity (Huang et al., 2012) and innovation sales (Vásquez-Urriago et al., 2016b), although Huang et al. (2012) found that larger firms benefit more than smaller firms in relation to market performance (measured as market share) from the on-park location. Arauzo-Carod et al. (2018) employ percentile regression and show that park location has a positive effect on sales and employment growth only in the case of high-growth firms.

Tenant firm age seems also to have an effect. Liberati et al. (2016) show that older firms benefit more from being on park in terms of sales, while Díez-Vial and Fernández-Olmos (2017a), who consider sales growth, employment growth and innovation sales, show that parks have a stronger effect for younger firms.

The level of internal R&D seems to enhance the park effect in terms of employment and sales growth (Díez-Vial & Fernández-Olmos, 2017a) and new product sales (Díez-Vial & Fernández-Olmos, 2015). Vásquez-Urriago et al. (2016b) show that firms that do not invest in R&D do not benefit from park location, but that even a low level of internal innovation effort results in high returns from park location.

A positive attitude from the firm’s managers to park activities and the time managers spend on park daily, affect the relationships among tenants (Koçak & Can, 2014). Ng et al. (2020) show that the perceived benefits sought by companies in STPs depend on the type of company and this influences the perceived benefit of park attributes.

Other firm-level characteristics that have been demonstrated to moderate the park effect include level of industry maturity (Díez-Vial & Fernández-Olmos, 2017b) and experience of previous collaboration with HEIs (Díez-Vial & Fernández-Olmos, 2015).

6 Conclusions and directions for further research

In this paper, we conducted a comprehensive and systematic review of the stream of work on STPs. We focused especially on quantitative studies aimed at evaluating the added value to firms of on-park location.

The interest of the academic community in STPs is rapidly growing, although the literature can be still considered at an embryonic stage (Hobbs et al., 2017a). Of the 221 papers reviewed, 59 papers (27%) have been published in the last 4 years.

Quantitative studies focus essentially on evaluating the returns to firms of on-park location, in relation to their economic performance, innovation performance and patterns of cooperation with other firms and with universities. Our review shows that, in the case of almost every variable studied, the evidence is contrasting. We conducted a regression analysis that shows that these contradictory results are mainly explained by the fact that studies using a small sample size of on-park firms are less likely to find statistically significant results. This finding may represent a key to go beyond the inconclusiveness of the literature on STP effects found in other studies: the absence of evidence cannot be interpreted as evidence of absence. We do not find a significant influence of the methodology employed, the time period considered or the country analysed. Although there is a large body of scholarly research on assessing the value-added of STPs to tenant firms, we believe that more empirical research is needed. Better datasets are becoming more available and this allows researchers to employ larger sample sizes and methodologies aimed at dealing with the endogeneity of STP location.

Some previous reviews on STPs (Henriques et al., 2018; Lecluyse et al., 2019) have indicated the need to consider the heterogeneous effects of on-park location, i.e. some characteristics of firms and parks make that some firms benefit more than others from on-park location and some parks have a greater effect on firms than others. We have found 19 quantitative papers explicitly taking into account heterogeneous effects. The review in this paper provides evidence of the existence of heterogeneous effects at both park and tenant firm level over several dimensions, like firm size, age or R&D intensity and park size, age, links with university or location. Only three of the papers reviewed conduct a joint analysis of park-level and firm-level heterogeneity. We believe that taking into account simultaneously firm and park characteristics would improve the matching and, consequently, increase the effects of STPs.

Other future lines of research are suggested hereinafter. First, we believe we need to better understand the channels through which the STP effect takes place; to this end, more evidence is needed on the role played by the services provided by park management, by the co-location with other on-park firms and the university and by image factors (e.g. park location reducing investors’ perceived risks and increasing customers’ trust). Filling these gaps would provide policymakers and managers with a better understanding of STPs. Second, within the stream of research analysing the role of STPs in their regional innovation systems, it would be useful to study the existence and extent of knowledge spillovers of parks, on firms located nearby, but outside their perimeters. Finally, in many countries, STPs are considered an important innovation and local development policy. Therefore, it is crucial to compare their costs and effects with the costs and effects of other policies, such as public venture capital programmes, technology grant/loan programmes, promotion of technology transfer from universities and research centres, high-technology business incubators, etc.

Notes

In addition to these reviews, there are other two papers with a regional focus. Poonjan & Tanner (2020) review 64 papers with the aim of developing a comprehensive framework of how regional contextual factors have been shown to play a role for STP performance. They distinguish five relevant regional factors: university and research institutes, industrial structure, institutional settings, financial support and urbanization. On the other hand, Theeranattapong et al. (2021) review the literature on the roles of the university in the Regional Innovation System actors-university-science park nexus. They distinguish three types of activities performed by the university: knowledge co-creation, acting as a conduit and inter-organisational relationship building and conclude that further research is needed on the relationship between Regional Innovation Systems and Science Parks, especially in peripheral regions.

The most frequent definitions are reported in Annex 1.

Some terms have achieved particular prominence in certain countries (e.g., STPs tend to be called Technopoles in the francophone world and Research Parks in the US) (Link & Scott, 2007; Shearmur & Doloreux, 2000). The European Union tried to differentiate among some of these terms (Scandizzo, 2005), but the most recent literature shows that its attempts have not been successful. There have been also some attempts to introduce a typology of STPs (Albahari et al., 2017; Ng et al., 2019).

Annex 1 provides the most frequent definitions of STPs and tries to explain the different roles played by STPs and incubators in their support for innovative firms.

In a different paper, Díez-Vial & Fernández-Olmos (2017b), use a different methodology and find no statistically significant effects on employment or sales growth.

Siegel et al. (2003b) find a positive effect on no. of patents, although when they control for endogeneity bias, the magnitude is quite small.

In this section, the term universities includes other HEIs and research centres.

However, they find no relevant effect on the economic returns from cooperation.

Which it can reasonably be supposed to come from contracts with on-park firms, although this is not specified in the paper.

Only 3 specifications yield (statistically significant) negative estimates. In the subsequent analysis, they are included in the group of specifications with non statistically significant positive estimates.

Gwebu et al. (2019) find a positive effect of the tenant-park alignment (a dummy variable coded as 1 if the tenant firm shares business focus with the park and otherwise 0), which is more likable to occur in specialized parks, on sales growth against peers.

The UKSPA definition refers to science parks.

The AURP definition refers to university research parks.

References

Abramovsky, L., & Simpson, H. (2011). Geographic proximity and firm-university innovation linkages: Evidence from Great Britain. Journal of Economic Geography, 11(6), 949–977. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbq052

Al-Kfairy, M., & Mellor, R. B. (2020). The role of organisation structure in the success of start-up science and technology parks (STPs). Knowledge Management Research & Practice. https://doi.org/10.1080/14778238.2020.1838962 in Press.

Al-Sultan, Y. Y. (1998). The concept of science park in the context of Kuwait. International Journal of Technology Management, 16(8), 800–807.

Albahari, A. (2015). Science and technology parks: Does one size fit all? In J. Tian Miao, P. Benneworth, & N. A. Phelps (Eds.), Making 21st century knowledge complexes: Technopoles of the world revisited (pp. 191–206). Routledge.

Albahari, A. (2019). Heterogeneity as a key for understanding science and technology park effects. In S. Amoroso, A. Link, & M. Wright (Eds.), Science and technology parks and regional economic development (pp. 143–157). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-30963-3_9

Albahari, A., Barge-Gil, A., Pérez-Canto, S., & Modrego, A. (2018). The influence of science and technology park characteristics on firms’ innovation results. Papers in Regional Science, 97(2), 253–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12253

Albahari, A., Catalano, G., & Landoni, P. (2013). Evaluation of national science park systems: A theoretical framework and its application to the Italian and Spanish systems. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 25(5), 599–614. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2013.785508

Albahari, A., Klofsten, M., & Rubio-Romero, J. C. (2019). Science and technology parks: A study of value creation for park tenants. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 44(4), 1256–1272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-018-9661-9

Albahari, A., Pérez-Canto, S., Barge-Gil, A., & Modrego, A. (2017). Technology parks versus science parks: Does the university make the difference? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 116(2017), 13–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.11.012

Aportela-Rodriguez, I. M., & Pacios, A. R. (2017). University libraries and science and technology parks: Reasons for collaboration. Libri, 67(3), 235–244. https://doi.org/10.1515/libri-2017-0007

Appold, S. J. (2004). Research parks and the location of industrial research laboratories: An analysis of the effectiveness of a policy intervention. Research Policy, 33(2), 225–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0048-7333(03)00124-0

Arauzo-Carod, J. M., Segarra-Blasco, A., & Teruel, M. (2018). The role of science and technology parks as firm growth boosters: An empirical analysis in Catalonia. Regional Studies, 52(5), 645–658. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1447098

Armanios, D. E., Eesley, C. E., Li, J., & Eisenhardt, K. M. (2017). How entrepreneurs leverage institutional intermediaries in emerging economies to acquire public resources. Strategic Management Journal, 38(7), 1373–1390. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2575

AURP. (2019). AURP. https://www.aurp.net/what-is-a-research-park

Bakouros, Y. L., Mardas, D. C., & Varsakelis, N. C. (2002). Science park, a high tech fantasy?: An analysis of the science parks of Greece. Technovation, 22(2), 123–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-4972(00)00087-0

Balle, A. R., Steffen, M. O., Curado, C., & Oliveira, M. (2019). Interorganizational knowledge sharing in a science and technology park: The use of knowledge sharing mechanisms. Journal of Knowledge Management, 23(10), 2016–2038. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-05-2018-0328

Barbera, F., & Fassero, S. (2013). The place-based nature of technological innovation: The case of Sophia Antipolis. Journal of Technology Transfer, 38(3), 216–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-011-9242-7

Bass, S. J. (1998). Japanese research parks: National policy and local development. Regional Studies, 32(5), 391–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343409850116808

Battelle Technology Partnership Practice. (2013). Driving Regional Innovation and Growth: Results from the 2012 Survey of North American University Research Park. https://aurp.memberclicks.net/assets/documents/aurp_batelllereportv2.pdf

Benneworth, P., & Ratinho, T. (2014). Reframing the role of knowledge parks and science cities in knowledge-based urban development. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 32(5), 784–808. https://doi.org/10.1068/c1266r

Berbegal-Mirabent, J., Alegre, I., & Guerrero, A. (2020). Mission statements and performance: An exploratory study of science parks. Long Range Planning, 53(5), 101932. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2019.101932

Bigliardi, B., Dormio, A. I., Nosella, A., & Petroni, G. (2006). Assessing science parks’ performances: Directions from selected Italian case studies. Technovation, 26(4), 489–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2005.01.002

Biswas, R. R. (2004). Making a technopolis in Hyderabad, India: The role of government IT policy. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 71(8), 823–835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2004.01.009

Bozzo, U. (1998). Technology park: An enterprise model. Progress in Planning, 49(3–4), 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-9006(98)00010-5

Brooker, D. (2013). From “wannabe” Silicon Valley to global back office? Examining the socio-spatial consequences of technopole planning practices in Malaysia. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 54(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/apv.12001

Bruton, G. D. (1998). Incubators as a small business support in Russia: Contrast of university-related U.S. incubators. Journal of Small Business Management, 36(1), 91–94.

Cabral, R. (1998). Refining the Cabral-Dahab science park management paradigm. International Journal of Technology Management, 16(8), 813–818. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.1998.002694

Cabral, R. (2004). The Cabral Dahab Science Park Management Paradigm applied to the case of Kista, Sweden. International Journal of Technology Management, 28(3/4/5/6), 419–443. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.2004.005297

Cadorin, E., Klofsten, M., & Löfsten, H. (2021). Science Parks, talent attraction and stakeholder involvement: An international study. Journal of Technology Transfer, 46(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-019-09753-w

Caldera, A., & Debande, O. (2010). Performance of Spanish universities in technology transfer: An empirical analysis. Research Policy, 39(9), 1160–1173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2010.05.016

Chan, K. F., & Lau, T. (2005). Assessing technology incubator programs in the science park: The good, the bad and the ugly. Technovation, 25(10), 1215–1228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2004.03.010

Chan, K. Y. A., Oerlemans, L. A. G., & Pretorius, M. W. (2010). Knowledge exchange behaviours of science park firms: The innovation hub case. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 22(2), 207–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537320903498546

Chan, K. Y. A., Oerlemans, L. A. G., & Pretorius, M. W. (2011). Innovation outcomes of South African new technology-based firms: A contribution to the debate on the performance of science park firms. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 14(4), 361–378.

Chen, C.-Y., Lin, Y.-L., & Chu, P.-Y. (2013). Facilitators of national innovation policy in a SME-dominated country: A case study of Taiwan. Innovation: Management, Policy & Practice, 15(4), 405–415. https://doi.org/10.5172/impp.2013.15.4.405

Chen, C., & Link, A. N. (2018). Employment in China’s hi-tech zones. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 14(3), 697–703. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-017-0486-z

Cheng, F., van Oort, F., Geertman, S., & Hooimeijer, P. (2014). Science parks and the co-location of high-tech small- and medium-sized firms in China’s Shenzhen. Urban Studies, 51(5), 1073–1089. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098013493020

Chordà, I. M. (1996). Towards the maturity stage: An insight into the performance of French technopoles. Technovation, 16(3), 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-4972(95)00042-9

Chou, T. L., & Lin, Y. C. (2007). Industrial park development across the Taiwan strait. Urban Studies, 44(8), 1405–1426. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980701373529

Claver-Cortés, E., Marco-Lajara, B., Manresa-Marhuenda, E., & García-Lillo, F. (2018). Location in scientific-technological parks, dynamic capabilities, and innovation. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 30(4), 377–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2017.1313404

Colombo, M. G., & Delmastro, M. (2002). How effective are technology incubators? Evidence from Italy. Research Policy, 31(7), 1103–1122. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0048-7333(01)00178-0

Corrocher, N., Lamperti, F., & Mavilia, R. (2019). Do science parks sustain or trigger innovation? Empirical evidence from Italy. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 147(October 2019), 140–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.07.005

Cricelli, L., Gastaldi, M., & Levialdi, N. (1997). A system of science and technology parks for the Rome area. International Journal of Technology Management, 13(2), 140–152. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.1997.001653

Cumming, D., Werth, J. C., & Zhang, Y. (2019). Governance in entrepreneurial ecosystems: Venture capitalists vs. technology parks. Small Business Economics, 52(2), 455–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9955-6

Dahab, S. S., & Cabral, R. (1998). Services firms in the IDEON science park. International Journal of Technology Management, 16(8), 740–750. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.1998.002696

del Castillo Hermosa, J., & Barroeta, B. (1998). The technology park at Beocillo: An instrument for regional development in Castilla-León. Progress in Planning, 49(3–4), 241–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-9006(98)00012-9

Dettwiler, P., Lindelöf, P., & Löfsten, H. (2006). Utility of location: A comparative survey between small new technology-based firms located on and off science parks—implications for facilities management. Technovation, 26(4), 506–517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2005.05.008

Díez-Vial, I., & Fernández-Olmos, M. (2015). Knowledge spillovers in science and technology parks: How can firms benefit most? Journal of Technology Transfer, 40(1), 70–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-013-9329-4

Díez-Vial, I., & Fernández-Olmos, M. (2017a). The effect of science and technology parks on firms’ performance: How can firms benefit most under economic downturns? Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 29(10), 1153–1166. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2016.1274390

Díez-Vial, I., & Fernández-Olmos, M. (2017b). The effect of science and technology parks on a firm’s performance: A dynamic approach over time. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 27(3), 413–434. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-016-0481-5

Diez-Vial, I., & Montoro-Sanchez, A. (2017). Research evolution in science parks and incubators: Foundations and new trends. Scientometrics, 110(3), 1243–1272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-2218-5

Durak, İ, Arslan, H. M., & Özdemir, Y. (2021). Application of AHP–TOPSIS methods in technopark selection of technology companies: Turkish case. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2021.1925242 in Press.

Durão, D., Sarmento, M., Varela, V., & Maltez, L. (2005). Virtual and real-estate science and technology parks: A case study of Taguspark. Technovation, 25(3), 237–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-4972(03)00110-X

de Ribeiro, J. A., Ladeira, M. B., de Faria, A. F., & Barbosa, M. W. (2021). A reference model for science and technology parks strategic performance management: An emerging economy perspective. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 59, 101612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jengtecman.2021.101612

de Mello, J. M. C., & Rocha, F. C. A. (2004). Networking for regional innovation and economic growth: The Brazilian Petrópolis technopole. International Journal of Technology Management, 27(5), 488–497. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.2004.004285

Echols, A. E., & Meredith, J. W. (1998). A case study of the Virginia Tech Corporate Research Center in the context of the Cabral-Dahab Paradigm, with comparison to other US research parks. International Journal of Technology Management, 16(8), 761. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.1998.002697

Eto, H. (2005). Obstacles to emergence of high/new technology parks, ventures and clusters in Japan. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 72(3), 359–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2004.08.008

Etzkowitz, H., & Zhou, C. (2018). Innovation incommensurability and the science park. R and D Management, 48(1), 73–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12266

European Commission. (2002). Benchmarking of business incubators. Brussels: European Commission.

Feldman, J. M. (2007). The managerial equation and innovation platforms: The case of Linköping and Berzelius science park. European Planning Studies, 15(8), 1027–1045. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310701448162

Felsenstein, D. (1994). University-related science parks—‘seedbeds‘ or ‘enclaves’ of innovation? Technovation, 14(2), 93–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-4972(94)90099-x

Ferguson, R. (2004). Why firms on science parks should not be expected to show better performance—the story of twelve biotechnology firms. International Journal of Technology Management, 28(3/4/5/6), 470–482. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijtm.2004.005305

Fernández-Alles, M., Camelo-Ordaz, C., & Franco-Leal, N. (2015). Key resources and actors for the evolution of academic spin-offs. Journal of Technology Transfer, 40(6), 976–1002. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-014-9387-2

Ferrara, M., Lamperti, F., & Mavilia, R. (2016). Looking for best performers: A pilot study towards the evaluation of science parks. Scientometrics, 106(2), 717–750. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1804-2

Fikirkoca, A., & Saritas, O. (2012). Foresight for science parks: The case of Ankara University. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 24(10), 1071–1085. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2012.723688

Fukugawa, N. (2006). Science parks in Japan and their value-added contributions to new technology-based firms. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 24(2), 381–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijindorg.2005.07.005

Gan, Q. Q., Hong, J., & Hou, B. J. (2021). Assessing the different types of policy instruments and policy mix for commercialisation of university technologies. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 33(5), 554–567. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2020.1831468

Garnsey, E., & Longhi, C. (2004). High technology locations and globalisation: Converse paths, common processes. International Journal of Technology Management, 28(3/4/5/6), 336. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.2004.005292

Gašparíková, J. (1998). The role of spin-off organisations and incubator centres (Science and technoparks and regional centres) in economic development. Ekonomicky Casopis, 46(6), 913–929.

Giaretta, E. (2014). The trust “builders” in the technology transfer relationships: An Italian science park experience. Journal of Technology Transfer, 39(5), 675–687. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-013-9313-z

Goldstein, H. A., & Luger, M. I. (1992). University-based research parks as a rural development strategy. Policy Studies Journal, 20(2), 249–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.1992.tb00153.x

González-Masip, J., Martín-de Castro, G., & Hernández, A. (2019). Inter-organisational knowledge spillovers: Attracting talent in science and technology parks and corporate social responsibility practices. Journal of Knowledge Management, 23(5), 975–997. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-06-2018-0367

Grasland, L. (1992). The search for an international position in the creation of a regional technological space: the example of montpellier. Urban Studies, 29(6), 1003–1010. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420989220080931

Guadix, J., Carrillo-Castrillo, J., Onieva, L., & Navascués, J. (2016). Success variables in science and technology parks. Journal of Business Research, 69(11), 4870–4875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.045

Guerrero, M., Urbano, D., Cunningham, J. A., & Gajón, E. (2018). Determinants of graduates’ start-ups creation across a multi-campus entrepreneurial University: The case of monterrey institute of technology and higher education. Journal of Small Business Management, 56(1), 150–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12366

Gwebu, K. L., Sohl, J., & Wang, J. (2019). Differential performance of science park firms: An integrative model. Small Business Economics, 52(1), 193–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0025-5

Hansson, F., Husted, K., & Vestergaard, J. (2005). Second generation science parks: From structural holes jockeys to social capital catalysts of the knowledge society. Technovation, 25(9), 1039–1049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2004.03.003

Harper, J. C., & Georghiou, L. (2005). Foresight in innovation policy: Shared visions for a science park and business-University links in a city region. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 17(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537320500088716

Hasan, S., Faggian, A., Klaiber, H. A., & Sheldon, I. (2018). Agglomeration economies or selection? An analysis of Taiwanese science parks. International Regional Science Review, 41(3), 335–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160017616642822

Hasan, S., Klaiber, H. A., & Sheldon, I. (2020). The impact of science parks on small- and medium-sized enterprises’ productivity distributions: The case of Taiwan and South Korea. Small Business Economics, 54(1), 135–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0083-8

Henriques, I. C., Sobreiro, V. A., & Kimura, H. (2018). Science and technology park: Future challenges. Technology in Society, 53(2018), 144–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2018.01.009

Hobbs, K. G., Link, A. N., & Scott, J. T. (2017a). Science and technology parks: An annotated and analytical literature review. Journal of Technology Transfer, 42(4), 957–976. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-016-9522-3

Hobbs, K. G., Link, A. N., & Scott, J. T. (2017b). The growth of US science and technology parks: Does proximity to a university matter? Annals of Regional Science, 59(2), 495–511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-017-0842-5

Hobbs, K. G., Link, A. N., & Shelton, T. L. (2020). The regional economic impacts of University research and science parks. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 11(1), 42–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-018-0566-5

Hommen, L., Doloreux, D., & Larsson, E. (2006). Emergence and growth of Mjärdevi Science Park in Linköping, Sweden. European Planning Studies, 14(10), 1331–1361. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310600852555

Howard, E. S., & Link, A. N. (2019). An oasis of knowledge: The early history of gateway University Research Park. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 10(3), 1037–1063. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-017-0513-x

Hu, A. G. (2007). Technology parks and regional economic growth in China. Research Policy, 36(1), 76–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2006.08.003

Hu, M. C. (2011). Evolution of knowledge creation and diffusion: The revisit of Taiwan’s Hsinchu Science Park. Scientometrics, 88(3), 949–977. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-011-0427-5

Hu, T.-S. (2008). Interaction among high-tech talent and its impact on innovation performance: A comparison of Taiwanese science parks at different stages of development. European Planning Studies, 16(2), 163–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310701814462

Hu, T.-S., Lin, C.-Y., & Chang, S.-L. (2005). Technology-based regional development strategies and the emergence of technological communities: A case study of HSIP, Taiwan. Technovation, 25(4), 367–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2003.09.002

Huang, K. F., Yu, C. M. J., & Seetoo, D. H. (2012). Firm innovation in policy-driven parks and spontaneous clusters: The smaller firm the better? Journal of Technology Transfer, 37(5), 715–731. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-012-9248-9

Huang, W.-J., & Fernández-Maldonado, A. M. (2016). High-tech development and spatial planning: Comparing the Netherlands and Taiwan from an institutional perspective. European Planning Studies, 24(9), 1662–1683. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1187717

IASP International Board. (2002).

Jenkins, J. C., Leicht, K. T., & Jaynes, A. (2008). Creating high-technology growth: High-tech employment growth in US metropolitan areas, 1988–1998. Social Science Quarterly, 89(2), 456–481. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2008.00542.x

Jimenez-Zarco, A. I., Cerdan-Chiscano, M., & Torrent-Sellens, J. (2013). Challenges and Opportunities in the Management of Science Parks: Design of a tool based on the analysis of resident companies. Review of Business Management, 15(48), 362–389. https://doi.org/10.7819/rbgn.v15i48.1503

Jongwanich, J., Kohpaiboon, A., & Yang, C.-H. (2014). Science park, triple helix, and regional innovative capacity: Province-level evidence from China. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 19(2), 333–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/13547860.2014.880285

Khanmirzaee, S., Jafari, M., & Akhavan, P. (2021). Analyzing the competitive advantage’s criteria of science and technology parks and incubators using DEMATEL approach. Journal of the Knowledge Economy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-021-00802-0 in Press.

Kihlgren, A. (2003). Promotion of innovation activity in Russia through the creation of science parks: The case of St. Petersburg (1992–1998). Technovation, 23(1), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-4972(01)00077-3

Kim, H.-Y., & Jung, C. M. (2010). Does a technology incubator work in the regional economy? Evidence from South Korea. Journal of Urban Planning and Development, 136(3), 273–284. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)UP.1943-5444.0000019

Kim, H., Lee, Y.-S., & Hwang, H.-R. (2014). Regionalization of planned S&T parks: The case of Daedeok S&T park in Daejeon, South Korea. Environment and Planning c: Government and Policy, 32(5), 843–862. https://doi.org/10.1068/c1269r

Koçak, Ö., & Can, Ö. (2014). Determinants of inter-firm networks among tenants of science technology parks. Industrial and Corporate Change, 23(2), 467–492. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtt015

Koh, F. C. C., Koh, W. T. H., & Tschang, F. T. (2005). An analytical framework for science parks and technology districts with an application to Singapore. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(2), 217–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2003.12.002

Koster, H. R. A., Cheng, F. F., Gerritse, M., & van Oort, F. G. (2019). Place-based policies, firm productivity, and displacement effects: Evidence from Shenzhen, China. Journal of Regional Science, 59(2), 187–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12415

Ku, Y. L., Liau, S.-J., & Hsing, W.-C. (2005). The high-tech milieu and innovation-oriented development. Technovation, 25(2), 145–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-4972(03)00074-9

Kulke, E. (2008). The technology park Berlin-Adlershof as an example of spatial proximity in regional economic policy. Zeitschrift Fur Wirtschaftsgeographie, 52(4), 193–208.

Lai, H., & Shyu, J. Z. (2005). A comparison of innovation capacity at science parks across the Taiwan Strait : The case of Zhangjiang High-Tech Park and Hsinchu Science-based Industrial Park. Technovation, 25, 805–813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2003.11.004

Lamperti, F., Mavilia, R., & Castellini, S. (2017). The role of science parks: A puzzle of growth, innovation and R&D investments. Journal of Technology Transfer, 42(1), 158–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-015-9455-2

Landoni, P., Scellato, G., & Catalano, G. (2010). Science Parks contribution to scientific and technological local development: The case of AREA science park trieste. International Journal of Technology, Policy and Management, 10(1–2), 36–52. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTPM.2010.032852

Laspia, A., Sansone, G., Landoni, P., Racanelli, D., & Bartezzaghi, E. (2021). The organization of innovation services in science and technology parks: Evidence from a mu. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 173(2021), 121095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121095