Abstract

This study suggests a comprehensive conceptualization of teacher knowledge for teaching early literacy in primary schools. Following the discourse on the professional knowledge of teachers, we argue that teachers’ knowledge relevant to support reading and writing at the beginning of primary school education is multidimensional by nature: Teachers need content knowledge (CK), pedagogical content knowledge (PCK), and general pedagogical knowledge (GPK). Although research on teacher knowledge has made remarkable progress over the last decade, and in particular in domains such as mathematics, relevant empirical research using standardized assessment that would allow in-depth analyses of how teacher knowledge is acquired by pre-service teachers during teacher education and how teacher knowledge influences instructional quality and student learning in early literacy is very scarce. The following research questions are focused on: (1) Can teachers’ professional knowledge for teaching early literacy be conceptualized in terms of CK, PCK, and GPK allowing empirical measurement? (2) How do teachers acquire such knowledge during initial teacher education? (3) Is teachers’ professional knowledge a premise for instructional quality in teaching early literacy to students? We present the conceptualization of teacher knowledge for teaching early literacy in primary schools in Germany as the country of our study and specific measurement instruments recently developed by our research group. Assessment data of 386 pre-service teachers at different teacher education stages is used to analyze our research questions. Findings show (1) construct validity of the standardized tests related to the hypothesized structure, (2) curricular validity related to teacher education, and (3) predictive validity related to instructional quality. Implications for teacher education and the professional development of teachers are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Broad agreement exists that teachers need professional knowledge for the successful mastering tasks that are typical for their profession. As early as in the 1980s, Shulman (1987) suggested to differentiate teacher knowledge into three components: content knowledge (CK), pedagogical content knowledge (PCK), and general pedagogical knowledge (GPK). Since then, many researchers have related their work on teacher knowledge, assuming these components can be identified and contribute to the effective teaching of students and their learning outcomes. During the last two decades, an increasing number of empirical studies have assessed teacher knowledge directly and provide evidence that teachers’ subject-specific knowledge and skills are decisive factors with respect to the achievement of their students (e.g., König et al., 2021; Hill et al., 2005; Baumert et al., 2010; Sadler et al., 2013). Moreover, research on teacher education effectiveness (Blömeke et al., 2008) has established the importance of measuring teacher knowledge as an outcome at various stages of teacher education (Kaiser & König, 2019).

Empirical studies that work with standardized assessments very often have a focus on the domain of mathematics (Ball et al., 2008; Baumert et al., 2010; Hill et al., 2005; Schmidt et al., 2007; Tatto et al., 2008). Mathematics is a core school subject worldwide (OECD, 2014) and therefore of great relevance. Nevertheless, the question arises how new insights proliferated by such empirical research are relevant to languages as well. Therefore, a number of studies have recently started to assess language teacher knowledge (König et al., 2016; König & Bremerich-Vos, 2020; Evens et al., 2018; Krauss et al., 2017), but they are predominantly focused on (foreign) language teaching at the secondary school level. In contrast, empirical investigation of primary school teachers’ knowledge, in particular with regards to teaching early literacy, is scarce.

Against this background, our article proposes a comprehensive conceptualization and operationalization of the professional knowledge of pre-service school teachers for teaching early literacy, who we directly assessed using standardized tests developed by our research group. Our investigation will be exemplified by assessment data from 386 pre-service teachers in Germany as a country in which German besides Mathematics constitute the core subjects taught at primary school. We first examine construct validity by looking at the structure of cognitive measures, namely pre-service teachers’ CK, PCK, and GPK. Second, we examine curricular validity by comparing such measures to specific learning opportunities pre-service teachers were exposed to at different stages during initial teacher education. Third, we ask whether teachers’ professional knowledge is a premise for instructional quality in teaching early literacy to students. The overall aim of this article is to contribute to a more precise outline of professional teacher knowledge for teaching early literacy and its relation to teacher education.

1.1 Literature survey

Teachers’ professional knowledge

Many scholars have emphasized that teacher knowledge contributes to effective teaching and student learning (Kaiser & König, 2019; König et al., 2021; Darling-Hammond & Bransford, 2007; Grossman & McDonald, 2008; Munby et al., 2001; Woolfolk Hoy et al., 2006; Gitomer & Zisk, 2015; Liu & Phelps, 2020). Over the last four decades, research on teacher expertise has provided evidence that teachers need professional knowledge for mastering typical professional tasks (e.g., Berliner, 2004; Stigler & Miller, 2018). In the 1980s, Shulman (1987) developed a classification of professional teacher knowledge components, referred to by many empirical researchers when distinguishing between content knowledge (CK), pedagogical content knowledge (PCK), and general pedagogical knowledge (GPK) (see, e.g., König et al., 2016; Baumert et al., 2010; Tatto et al., 2012; Krauss et al., 2017).

Teachers’ CK is related to the specific subject and the content of teaching. It is shaped by academic disciplines underlying the subject (Freeman, 2002). For example, in the comparative Teacher Education and Development Study in Mathematics (TEDS-M), mathematical content knowledge of future primary and secondary school teachers was assessed in 17 countries worldwide and comprised the following content areas: number, geometry, algebra, and data (Tatto et al., 2008, p. 36). Recently, König and Bremerich-Vos (2020) have conceptualized the CK of the German language teacher for the secondary level into knowledge of linguistics and literature, evidenced by a structural analysis using Rasch scaling models.

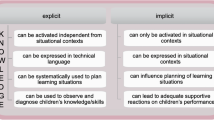

Teachers’ GPK, in contrast, is not bound to a particular teaching subject. As Shulman (1987, p. 8) pointed out, it involves “those broad principles and strategies of classroom management and organization that appear to transcend subject matter” and comprises knowledge about learners and learning, assessment, and educational contexts and purposes. A systematic review recently conducted by the OECD provided evidence that three broader fields have been covered by empirical research on GPK over the last decades: knowledge of instructional process (e.g., teaching methods, classroom management); student learning (e.g., individual dispositions of students and their learning processes); and assessment (e.g., diagnosing principles and evaluation procedures) (König, 2014).

Building on CK and GPK, Shulman (1987, p. 8) introduced the notion of PCK as the subject-specific knowledge for the purpose of teaching and argued that PCK serves as the “category most likely to distinguish the understanding of the content specialist from that of the pedagogue.” Following Shulman, many scholars have applied his definition of PCK for the domain of mathematics. For example, Bukova-Güzel (2010, p. 1873), in reviewing previous work such as Grossman (1990), Schoenfeld (1998), and Shulman (1987), developed a framework, in which PCK comprises teacher knowledge of curriculum, knowledge of learners, and knowledge of teaching strategies and multiple representations. In turn, empirical studies that operationalized PCK in order to test teachers made use of such differentiations. For example in TEDS-M, PCK of future primary and secondary school teachers of mathematics was defined as the knowledge about the teaching and learning of mathematics as well as curricular knowledge (Blömeke & Delaney, 2012, p. 225; Tatto et al., 2008)

Although broad agreement exists that the teacher professional knowledge base comprises at least the three knowledge components CK, PCK, and GPK (Grossman & Richert, 1988), hardly any empirical study has investigated the question how these cognitive components are interrelated. For example, PCK may serve as knowledge category that draws on both CK and GPK as foundations. While theoretical distinctions have been pointed out, empirical educational research has not provided clear answers with respect to the differentiations proposed. Existing studies in mathematics either show that CK and PCK are very highly intercorrelated (Blömeke et al., 2011a, 2011b; Krauss et al., 2008) or even suggest that CK and PCK could be merged into one knowledge category (Hill et al., 2005). None of these analyses has systematically accounted for the significance of GPK, therefore leaving open the question of whether teachers’ PCK draws on both CK and GPK. For German language secondary teachers, the recent study by König and Bremerich-Vos (2020) integrated all three knowledge components, showing that PCK of German language teachers was more highly intercorrelated with their CK of linguistics and literature than with their GPK. How CK, PCK, and GPK are interrelated in case of teachers’ professional knowledge for teaching early literacy remains an open question though.

Teaching early literacy

In many countries worldwide, agreement exists that developing reading and writing literacy is indispensable for children’s growth, education, and daily life (Kucirkova et al., 2017; Mullis & Martin, 2019; Neuman et al., 2003). In Germany as the country of our study, the national standards for primary education established in 2004 specify to provide primary school students with a fundamental language education for being able to deal with present and future life situations (KMK, 2004a, 2004b). Early literacy instruction should promote children’s interest in reading and writing and acquiring basic reading and writing skills (KMK, 2004a, 2004b).

Whereas these educational goals related to teaching early literacy are binding regulations (KMK, 2004a, 2004b), disagreement exists about the specific teaching methods to reach these goals in primary schools. As a consequence, there are different concepts on how to teach basic reading and writing skills. These concepts differ from one another with regard to their principles of written language and their understanding of teaching and learning. A distinction is made between concepts that are course-oriented and learning path-oriented, depending on whether teachers or learners fulfill an active role in initial reading and writing instruction at primary school.

Course-oriented concepts such as traditional primer courses aim at introducing the learner to the subject of written language in a linear way. Among these concepts, there is variation again: On the one hand, there are classical phonographically oriented approaches that combine analytic and synthetic methods of teaching and writing. On the other hand, approaches with the main focus on syllables can be found. One specific syllables-based approach that differs a lot from the classical syllable primer is a more systematic-linguistic-oriented concept. It is based on getting insights into the prototypical structure of German words (two-syllabled trochaic words with a stressed or unstressed accentuation). For this purpose, a visual tool was constructed: the so-called house-model (Häuser-Modell). These models represent the four basic German word structures in a child-oriented way and should simplify the process of understanding the German orthographic system (Röber, 2009; Budde et al., 2012).

Concepts such as language experience approaches (Spracherfahrungsansätze) and the method of “writing to read” (Lesen durch Schreiben; Reichen, 2008) can be seen as learning path oriented. A main characteristic of the language experience approach is the focus on individual learning paths of children and their language experiences during the initial reading and writing instruction. Gaining language experience means to deal with written language in authentic and meaningful situations. The approach’s overall aim is to have learners developing, expanding, and differentiating their individual access to written language (Brügelmann & Brinkmann, 1998). Similar to the language experience approach, the “writing to read” method includes the learners’ language experience but mainly targets on spoken language. Therefore, students’ own words, which are preferably spoken the way they are written, that is, the pronunciation matches the phonetic spelling, become the subject of spoken language analyses. Finally, the isolated individual phonemes are connected to graphemes. A “Speaking Table of Letters and Sounds” (Anlauttabelle), which assigns single letters to sounds via visual symbols, provides orientation for the learners. It aims at enabling children to learn to read by frequent writing. Often, mixed forms of learning path and course-oriented concepts can be found in early literacy instruction.

For decades, it has been discussed by researchers and practitioners which method proves to be particularly the most effective for the acquisition of reading and writing skills. A meta-analysis has provided evidence that the different teaching methods do not influence primary students’ writing and reading skills at the end of grade four in German schools significantly (Funke, 2014). Instead, new insights from research on the professional knowledge of teachers give rise to better focus the importance of teacher’s professional knowledge for instructional quality and student learning.

Prior empirical research on teachers’ knowledge for early literacy

Empirical educational research on teachers’ professional knowledge for teaching early literacy is scarce. Approaches in language domains mainly focus on the secondary school level (König et al., 2016; König & Bremerich-Vos, 2020; Blömeke et al., 2011a, 2011b). Those for the primary school level (Evens et al., 2018; Rutsch and Dörfler, 2017) mostly do not cover teachers’ professional knowledge regarding early literacy instruction. Occasionally, single approaches can be found that analyze professional knowledge concerning early literacy acquisition and advanced literacy acquisition: Riegler and Wieprächtiger-Geppert (2016) for example developed an instrument to record the professional knowledge of primary school teachers about orthography and orthographic acquisition. Toro and Irene(2013) analyzed teachers’ CK and PCK about basic reading and writing acquisition by means of a three-part questionnaire. In Corvacho del Toro’s study, only the items that refer to the CK constitute reliable scales, but not the items that refer to the PCK. The study’s results highlight the importance of primary teachers’ CK regarding orthography especially for weaker students’ writing skills such as spelling performance (Toro and Irene, 2013). Internationally, a study by Carlisle et al. (2009) examined not only CK, but also PCK. Regarding initial reading, it has been shown that PCK has a greater impact on students’ performance outcome than CK. The existing findings are ambiguous since the professional knowledge about written language acquisition is modeled and operationalized differently (Jagemann, 2018).

1.2 The study: teachers’ professional knowledge for teaching early literacy

Context of study

In Germany, initial teacher education is organized into two phases. First, pre-service teachers attend a German university with programs that emphasize academic, theoretical studies. A bachelor’s degree usually takes 3 years of study; future teachers will then study for 2 more years and finish university with a Master’s degree. After graduation, pre-service teachers enter the second phase of pre-service teacher education. Usually, it takes 1.5 years. This second phase can be regarded as induction. Pre-service teachers are asked to apply their knowledge in teaching and they work part-time at schools and attend courses in general pedagogy and subject-specific pedagogy; the study of subject-matter content is no longer part of this second phase. The second phase ends with the State Examination (Staatsexamen). During induction, a committee assesses pre-service teachers. Across the two phases, there are two possible programs in which pre-service teachers acquire professional knowledge for teaching early literacy. They pursue either a career for primary schools or a career for special needs schools.

Research questions and hypotheses

We asked the following research questions: (1) Can teachers’ professional knowledge for teaching early literacy be conceptualized in terms of CK, PCK, and GPK allowing empirical measurement (RQ 1)? (2) How do teachers acquire such knowledge during initial teacher education (RQ 2)? (3) Is teachers’ professional knowledge a premise for instructional quality in teaching early literacy to students (RQ 3)?

Regarding RQ 1, we predicted that pre-service teachers’ professional knowledge for teaching early literacy is not homogeneous but organized according to domains. This means that we assumed that professional knowledge is multidimensional. Alternatively, pre-service teachers’ professional knowledge would be homogeneous or one-dimensional. Technically speaking, the latter would imply an Item-Response Theory (IRT) scaling model in which only one latent variable was specified by all test items. Model 1 in Fig. 1 shows a graphical representation of this idea.

Regarding RQ 2, we consider the aim of initial teacher education programs to prepare well-qualified pre-service teachers (European Commission, (2013) ; KMK, 2004a, 2004b/2019, 2008/2019). Among other goals that might be pursued, such programs intend pre-service teachers acquire professional knowledge. Thus, subject-related but also general pedagogical opportunities to learn are provided by teacher education institutions (König et al., 2017; Schmidt et al., 2007). Since teacher education in Germany claims to be effective and the conceptualization of our tests measuring CK, PCK, and GPK suggests that all dimensions underlying the test instrument are curricular valid with regard to German teacher education, we assume to measure continuous knowledge gain of future teachers across the different stages of teacher education (bachelor studies, Master studies, induction).

With RQ 3, we refer to an analysis of predictive validity pre-service teacher knowledge has for the quality of instruction while teaching during their practical opportunities to learn. In the present study, Master students were surveyed at the end of their long-term practicum in schools which has a duration of 5 months. Pre-service teachers during induction are required to teach a limited number of lessons every week, so both groups should be able to report on the quality of the instruction they have delivered to their students. We assume positive correlations between pre-service teacher knowledge scores and basic dimensions of instructional quality such as effective classroom management, cognitive activation, and constructive support of students.

2 Method

2.1 Sampling design

Data are available from n = 386 pre-service teachers in Germany during their bachelor studies, Master studies, and induction (see Table 1). Their CK, PCK, and GPK were tested as part of quality assurance during teacher education at the University of Cologne in Germany, one of the largest teacher education universities in Germany and Europe. The quality assurance is part of a larger teacher education project (Zukunftsstrategie Lehrer*innenbildung Köln (ZuS): Inklusion und Heterogenität gestalten) that was launched in 2015. Two teaching types were focused on: pre-service teachers who qualify to teach at primary schools and pre-service teachers who qualify to teach at special needs schools. Both teaching types are exposed to the same learning opportunities in teaching early literacy at the University of Cologne (Hanke & Pohl, 2020). The majority of pre-service teachers are female (92%), which is fairly typical for primary teacher education in Germany (Blömeke et al., 2010, p. 138).

Pre-service teachers were surveyed during their teacher education courses. During bachelor studies, data collection could be carried out in large lectures, whereas during Master studies and induction, students had to be surveyed in small seminars. Since therefore bachelor students could be better reached, their response rates were higher and the sample is larger (Table 1). Pre-service teachers during induction were difficult to reach, resulting in a small sample which will later be discussed as a limitation of our sampling design.

Whereas the three groups differ by age on average (F(2,385) = 59.84, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.24), their mean grade point average (GPA, in German Abiturnote) does not show any statistically significant difference (F(2,381) = 1.37, p = 0.254, η2 < 0.01). Due to entrance selection at the University of Cologne (numerus clausus), average GPA of the pre-service teachers is fairly good.

2.2 Tests of CK, PCK, and GPK

When developing a comprehensive instrument for measuring primary school teachers’ professional knowledge for teaching early literacy, we basically considered that PCK would have to go beyond an “amalgam of content and pedagogy” (Shulman, 1987, p. 8). The German writing system is closely related to the spoken system more than it is the case in other languages. However, it is clearly a mixed system based on further structure-forming principles such as syllabic, morphological, and syntactic ones (that are not part of spoken language in this form). This combination of principles primarily constitutes the reception process (Maas, 2015). The complex system of written language evokes specific acquisition phenomena in the learning process, including mistakes in spelling or reading, as well as specific learner-internal acquisition strategies, which are for instance expressed by structural hypothesis-forming processes including possible over-generalization. Accordingly, we also assume a fundamental separation of professional knowledge into CK and PCK, but concerning the latter, we differentiate between aspects related to acquisition and aspects related to mediation (similar to König et al., 2016, for Teaching English as a Foreign Language). Table 2 serves as an overview of aspects and facets of teachers’ professional knowledge for teaching early literacy.

The operationalization of the selected domain- and target group-specific content aspects of professional knowledge for teaching early literacy follows both a content (knowledge areas) and a qualitative (type of knowledge) classification. CK with an emphasis on basic knowledge of linguistics accounts for aspects of graphology, phonology, morphology, orthography, syntax, and the reading process. PCK implies acquisition-related, development-related, and diagnostic knowledge as well as curricular and methodological knowledge related to teaching. In terms of quality, a distinction is made between declarative and procedural knowledge in both areas of knowledge, since, as especially the research on teacher expertise has worked out, both declarative and procedural knowledge contribute to the expert’s performance in the classroom (Stigler, & Miller, 2018). The test includes both single-choice tasks and more complex tasks with open and closed task format (see Table 3 for item examples). Table 2 provides an overview of the item matrix and the distribution of the 43 items. In total, CK comprises basic knowledge in linguistics (14 items); PCK deals with knowledge about student learning and development (7 items), curricular knowledge (8 items), diagnostic knowledge (4 items), and knowledge about teaching strategies (10 items).

By giving priority to a greater number of items measuring PCK, we intend to consider the specific acquisition constellation in case of the early literacy acquisition within the first two school years. In contrast to later phases, in which CK may be prioritized, in the present case, the facets of PCK are to be accentuated or to be examined more precisely. In addition, four requirements were taken into consideration when designing the survey instrument:

Concept neutrality

All current teaching concepts that are implemented in the practice of teaching are accounted for the instrument without preferring a specific teaching method as outlined previously (e.g., course oriented and learning path oriented approaches). Nevertheless, critical knowledge of the existing teaching methods is also collected.

Teaching proximity

Wherever possible, various instructional examples, such as learner’s written material and texts, textbook assignments, and teaching materials, were added to the items. However, core components of linguistic and didactic terminology were not neglected.

Ecological validity

We ensured that the knowledge specified by the instrument corresponds with well-known basics on the acquisition of early literacy.

Normativity

A survey of experts with both university professors and induction teacher educators was conducted to examine content validity, i.e., confirming the relevance of the different knowledge facets for the acquisition of teaching early literacy during teacher education (Bruckmann et al., 2019).

While tests measuring CK and PCK for teaching early literacy were newly developed, in the present study, we used an existing GPK test that was developed in the context of the international comparative study TEDS-M (König et al., 2011). The test assesses GPK that is related to generic dimensions of teaching quality and, therefore, measures knowledge allowing teachers to prepare, structure, and evaluate lessons (“structure”), to motivate and support students, as well as manage the classroom (“motivation/classroom management”), to deal with heterogeneous learning groups in the classroom (“adaptivity”), and to assess students (“assessment”). Table 3 contains two-item examples illustrating the subareas “motivation/classroom management” and “structure.” In TEDS-M and further studies, evidence for reliability of the test could be provided (König et al., 2011). For example, the overall reliability of the test is 0.78 in König et al. (2011, p. 194). In the study by König and Pflanzl (2016), correlations between GPK and generic dimensions of teaching quality are 0.33 (GPK and effective classroom management), 0.47 (GPK and teaching methods/teacher clarity), and 0.51 (GPK and teacher-student relationships). Due to time constraints in the present study, we used a shorter version with 40 items only (for a more detailed description of the test, see, e.g., König et al., 2011; König, 2014).

2.3 Instructional quality

Those pre-service teachers who had been exposed to substantial practical learning opportunities were additionally required to respond to a scale inventory with which we captured self-reported instructional quality. The scale inventory was developed in a previous study (Depaepe & König, 2018). It relates to the concept of three basic dimensions of instructional quality applied to primary level reading and writing instruction (Stahns et al., 2020). Each basic dimension is measured by two subscales with three or four Likert-items, ranging from 1 (“fully disagree”) to 4 (“fully agree”). Cognitive activation was measured using the subscales “cognitive demanding tasks” (3 items, e.g., “I asked the students questions they had really to think of.”) and “stimulating students’ cognitive independence” (3 items, e.g., “When working on challenging tasks, I allowed students to apply their own strategies.”). To measure effective classroom management, the subscales “preventing disorder” (4 items, e.g., “I always knew exactly what happened in the classroom.”) and “providing structure” (4 items, e.g., “I frequently told the students what they had to remember.”) were used. Constructive support was measured using the subscales “encouraging students” (4 items, e.g., “I showed an interest in every student’s learning.”) and “differentiated instruction” (3 items, e.g., “The single students often had different tasks.”).

2.4 Scaling and data analysis

The data allows empirical analyses of the standardized tests for the total sample (RQ 1) as well as for the pre-service teachers in different stages of their professionalization (RQ 2). In addition, pre-service teachers in their Master studies who had to teach during their long-term practicum (for 5 months) and pre-service teachers during induction were asked to provide self-reports about the instructional quality of their lessons delivered to their students. Using these two groups of advanced pre-service teachers allows empirical analyses related to RQ 3.

For answering RQ 1, we did the model comparison between three-dimensional model (right side in Fig. 1) and one-dimensional model (left side in Fig. 1) by using the Conquest software package (Wu et al., 1997), allowing a likelihood ratio test, deviance statistics, Akaike information criterion (AIC), and Bayesian information criterion (BIC). All cases were included in the modeling, thus effectively increasing the analytical power of the scaling analysis (Bond & Fox, 2007). The deviance statistics (i.e., − 2*log likelihood) of the model is calculated of which the smaller the model fitted the data better. We examined the empirical reliability of each scale by using Expected a Posteriori estimation (EAP; de Ayala, 1995) which allows an unbiased description of population parameters (Wu et al., 1997). We also use indices of infit and outfit mean square error (MNSQ) that can be reported by Conquest. When all the items are below 1.4 (Wright & Linacre, 1994), items fit the specific scaling model. For answering RQ 2, we used IRT test scores by fitting the three-dimensional model (EAP estimates derived from Conquest scaling analysis) to present descriptive statistics for CK, PCK, and GPK and to implement analysis of variance (ANOVA) for comparing the CK, PCK, and GPK means between the groups of bachelor students, Master students, and pre-service teachers during induction. For answering RQ 3, the correlation between IRT test scores (EAP estimates) and the six subtests of instructional quality were calculated.

3 Results

3.1 Empirical findings on the structure of professional knowledge

RQ 1 concerns the structure of teacher knowledge for teaching early literacy. We examined whether the items to test pre-service teachers’ CK, PCK, and GPK would serve as indicators of one general factor. This model was compared with a model in which the CK, PCK, and GPK were specified as three latent variables by the relevant test items (see Fig. 1). Table 4 contains information on the deviance statistics (i.e., − 2*log likelihood) of each model. AIC and BIC were calculated as well, since both are based on the deviance statistics and account for the number of parameters as well as sample size. The findings allow us to assume the hypothesized multidimensionality rather than the one-dimensionality of pre-service teachers’ knowledge. The relative Chi-square (i.e., the ratio of the Chi-square deviance and the degrees of freedom) shows a statistically significant improvement of the three-dimensional model. AIC and BIC are lower for the three-dimensional model than for the one-dimensional model. As the weighted mean square item fit statistics of the three-dimensional model show, they range between 0.78 and 1.18 for all 82 items, therefore fitting the three-dimensional framework (Wright & Linacre, 1994).

Table 5 contains the latent intercorrelations for pre-service teachers’ CK, PCK, and GPK. High latent intercorrelations (> 0.8) are between PCK and CK on the one side and moderately high intercorrelation (> 0.5) between PCK and GPK on the other side. By contrast, medium size intercorrelation can be found with respect to the relation between GPK and CK (> 0.3).

To test for differences in degree of intercorrelation, we used the significance test proposed by Meng et al. (1992). As we had expected, the intercorrelation between CK and PCK is significantly higher than the intercorrelation between CK and GPK (z = 13.87, p < 0.001); and GPK is more highly intercorrelated with PCK than with CK (z = 7.76, p < 0.001). These differences may reflect the fact that CK and GPK are more distant from each other, whereas PCK relies on both knowledge of content and knowledge of pedagogy (Shulman, 1987). Interestingly, and contrary to our expectations, PCK and CK are intercorrelated more highly than PCK and GPK (z = 7.70, p < 0.001). This might be caused by the subject-specific emphasis given to PCK testing in our approach.

Figure 2 shows an item–person map from the multidimensional IRT analysis. On the left side, the abilities of future teachers are represented (one “X” represents 2.5 pre-service teachers), whereas on the right side, the distribution of test items is shown (each of the 82 test items has a number). If the location of an item and a person match, the person has a probability of 0.5 to succeed on that item. The higher a person is above an item on the scale, the more likely the person will succeed on the item. The lower a person is below an item on the scale, the more likely the person will be unsuccessful on the item. All three tests cover the pre-service teachers’ abilities quite well, as the range of person abilities (left side) was well covered by item difficulties (right side). The three-dimensional model and its results show that it was possible to create a test score for each knowledge dimension. The reliability was good (i.e., empirical reliability where the standard error was computed using EAP estimation, see Brown & Croudace, 2015) for CK (0.677), PCK (0.794), and GPK (0.818).

3.2 Descriptive findings on professional knowledge

Regarding RQ 2, findings show that the more advanced pre-service teachers are in the course of their initial teacher education, the higher they perform on all three knowledge assessments (Fig. 3). To facilitate reading, EAP estimates were linearly transformed to a mean of 500 and a standard deviation of 100 for each of the CK, PCK, and GPK scales, respectively. Whereas bachelor students’ average test scores are clearly below 500, Master students score around 550 and the test scores of pre-service teachers during induction are even slightly higher. In particular, pre-service teachers during induction reach an average score of 600 in the GPK assessment, which is about half a standard deviation higher than the test score of Master students and more than one standard deviation higher compared to bachelor students.

Findings from ANOVA show that group mean differences are statistically significant and practically relevant (CK, F(2,283) = 16.1, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.08; PCK, F(2,383) = 30.2, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.14; GPK, F(2,383) = 45.1, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.19). However, as post hoc tests for comparing the single groups show, concerning CK, PCK, and GPK, only bachelor students are outperformed by Master students and pre-service teachers during induction, but there are no significant mean differences between Master students and pre-service teachers during induction. One reason might be the small sample size of pre-service teachers during induction which causes large standard error (see Fig. 3). Since hypothesis testing always depends on sample size, we also computed effect size d (Cohen, 1992) to get further insights. There is no practically relevant effect when Master students and pre-service teachers during induction are compared towards their CK (0.08) and PCK (0.13); however, effect is almost medium when their GPK is compared (0.47). In contrast, there are medium to large effects when bachelor and Master students are compared (CK/PCK/GPK 0.64/0.87/1.02) or when bachelor students and pre-service teachers during induction are compared (0.76/1.01/1.35).

3.3 Findings on predictive validity of professional knowledge

To investigate RQ 3, we selected the subsample of those pre-service teachers in their Master studies or induction phase, since they had been sufficiently exposed to practical learning opportunities and thus be able to respond to a scale inventory measuring six aspects of instructional quality. Moreover, we only considered those pre-service teachers to be able to give valid judgements who had been trained for teaching a whole class. So, we only selected pre-service teachers that qualified for teaching in primary schools and who were either in their Master studies or induction (n = 57).

Table 6 provides findings from three intercorrelational analyses that were separately carried out for each of the three knowledge tests due to sample size. Statistically significant correlations are among pre-service teachers’ CK and PCK and the basic dimension of effective classroom management (subscale “Preventing disorder”). That means, the better the pre-service teachers scored in the CK and PCK assessment, the higher they rated items related to self-reported effective classroom management they provided when teaching during practical learning opportunities. Surprisingly and against our expectations, none of the other instructional quality scales was significantly correlated with the knowledge assessments.

4 Discussion

In the present study, we suggested a comprehensive conceptualization of teacher knowledge for teaching early literacy in primary schools. Starting from the discourse on the professional knowledge of teachers, as outlined by Shulman (1987) and the teacher expertise research, we argued that teachers’ knowledge relevant to support reading and writing at the beginning of primary school education is multidimensional by nature. Teachers who teach students at early grades are not just generalists. Instead, they need CK, PCK, and GPK. Therefore, we investigated pre-service teachers’ knowledge towards its structure (construct validity), how it is acquired during initial teacher education (curricular validity), and examined its significance for self-reported instructional quality (predictive validity). In a previous expert survey, we had already provided evidence for content validity of tests (Bruckmann et al., 2019). Although the context of our study is Germany, we think that all our research questions are of principle nature, therefore contributing to the larger scientific discourse on teachers’ professional knowledge going beyond the German speaking context.

4.1 Conceptualization of professional knowledge

Three standardized tests were used to directly assess pre-service teachers’ professional knowledge for teaching early literacy. In an IRT-scaling analysis, it turned out that a three-dimensional model which differentiated among CK, PCK, and GPK fitted significantly better to the data than a one-dimensional model in which teacher knowledge was operationalized across all test items. PCK was more closely correlated with CK on the one side and GPK on the other side, which confirms Shulman’s notion of PCK being an amalgam of both content and pedagogy (Shulman, 1987). Moreover the correlation between PCK and CK is in accordance with empirical studies in the area of mathematics and secondary level language teaching that also provided evidence that PCK is closely related to CK (König et al., 2016; König & Bremerich-Vos, 2020; Ball et al., 2008; Blömeke et al., 2011a, 2011b; Krauss et al., 2008).

Our findings underline the necessity to differentiate teacher knowledge components as suggested by Shulman (1987) and to consider teacher knowledge a multidimensional construct. Although previous studies that investigated the trias of CK, PCK, and GPK for different domains and school levels (e.g., English as a foreign language in secondary school level, König et al., 2016) have made visible the necessity for differentiating, the present study presumably has additional value: Disagreement exists as to what extent primary school teachers actually need subject-specific professional knowledge or, in contrast, whether only GPK would be sufficient for teaching at the primary level (Blömeke et al., 2011a, 2011b). As we found empirical evidence for separating the three knowledge components, we can interpret this as an important argument in favor of subject specialization even on the primary school level.

4.2 Professional knowledge acquisition

Regarding RQ 2, we intended to explain the variation in teacher knowledge for teaching early literacy in terms of the different training stages of pre-service teachers. Longitudinal data was not available, so we analyzed statistical mean differences among pre-service teacher groups to explore how knowledge might be acquired in the course of training. As expected, test scores varied across pre-service teachers from different stages, adequately reflecting differences in the learning opportunities they had been exposed to during their teacher education.

Pre-service teachers at a later stage (Master studies, induction) outperformed those at an earlier stage (bachelor studies) at university. Statistically significant mean differences were restricted to these groups, since sample size of pre-service teachers during induction was very small (n = 17), thus causing large standard errors (Fig. 3). Concerning GPK, however, at least the numeric values of average test scores were much higher (nearly half a standard deviation) for pre-service teachers during induction than during Master studies, reflected by almost medium size effect (d = 0.47). Thus, it is not surprising that previous studies that applied the GPK test to different groups of pre-service teachers showed statistically significant mean differences between Master students and pre-service teachers during induction (e.g., König et al., 2016, for pre-service secondary teachers for TEFL).

To sum up, test score differences by teacher education stage as shown in our study are well aligned to certain priorities laid down in the initial teacher education curriculum. That both CK and PCK are fostered during initial teacher education is a finding worth considering for the professionalization of primary teachers, whose knowledge base has sometimes been trivialized either to a minimum of CK or to GPK only. We also consider this as evidence for curricular validity of the tests.

4.3 Professional knowledge as a premise for instructional quality

Since CK and PCK standardized tests for teaching early literacy have been recently developed, we finally were interested in an analysis of predictive validity related to instructional quality. While for GPK, evidence for predictive validity has been provided in several previous studies targeting pre-service teachers (König & Kramer, 2016; Depaepe & König, 2018) as well as in-service teachers (König & Pflanzl, 2016; König et al., 2021); an examination of CK and PCK might reveal completely new insights.

Since, for validity reasons, we had to select a subsample, we focused on those pre-service teachers who had already been exposed to a substantial amount of teaching experience (n = 57). Findings related to our RQ 3 are limited, though. Only pre-service teachers’ CK and PCK were correlated with a key facet of effective classroom management (“preventing disorder”), whereas, in contrast, no other correlations could be found. One reason might be that the measurement quality of instructional quality through self-reports is limited. Another limitation might be that pre-service teachers have difficulties in self-evaluating their instructional practice delivered to students. Moreover, evidence exists that novice teachers usually are overwhelmed by the complexity of teaching situations. They highlight teaching challenges in terms of effective classroom management as one of the most important problems (Maulana et al., 2017). At the same time, however, they indicate that they are not sufficiently prepared to mastering these challenges (Jones, 2006). This could be another explanation that systematic variation among pre-service teachers is primarily among those categories (see Table 6).

4.4 Limitations

Although findings of the present study are promising, limitations exist as well. First, sample size of the more advanced pre-service teachers was relatively small and our sampling design did not allow longitudinal analysis models. Second, we only assessed pre-service teachers, whereas it remains an important issue to target in-service teachers as well. Third, our analysis of predictive validity was limited for reasons already mentioned. Future research should apply different approaches to capture instructional quality, such as in vivo rating or video-recordings of lessons (e.g., König et al., 2021). Fourth, predictive validity should be examined using student assessment data as well, in order to assure that teachers’ professional knowledge for teaching early literacy is decisive for student progress. Most of these shortcomings are considered in a current project that is carried out by our research group. Therefore, these research desiderata have been focused on already and new findings will be proliferated in the near future.

References

Ball, D. L., Thames, M. H., & Phelps, G. (2008). Content knowledge for teaching: What makes it special? Journal of Teacher Education, 59(5), 389–407.

Baumert, J., Kunter, M., Blum, W., Brunner, M., Voss, T., Jordan, A., & Tsai, Y. (2010). Teachers’ mathematical knowledge, cognitive activation in the classroom, and student progress. American Educational Research Journal, 47, 133–180.

Berliner, D. C. (2004). Describing the behavior and documenting the accomplishments of expert teachers. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 24, 200–212.

Blömeke, S., & Delaney, S. (2012). Assessment of teacher knowledge across countries: A review of the state of research. ZDM Mathematics Education, 44(3), 223–247.

Blömeke, S., Felbrich, A., Müller, C., Kaiser, G., & Lehmann, R. (2008). Effectiveness of Teacher Education. ZDM, 40(5), 719–734.

Blömeke, S., Houang, R., & Suhl, U. (2011). TEDS-M: Diagnosing teacher knowledge by applying multidimensional item response theory and multi-group models. IERI Monograph Series: Issues and Methodologies in Large-Scale Assessments, 4, 109–126.

Blömeke, S., Suhl, U., & Kaiser, G. (2011). Teacher education effectiveness: Quality and equity of future primary teachers’ mathematics and mathematics pedagogical content knowledge. Journal of Teacher Education, 62(2), 154–171.

Blömeke, S., Buchholtz, C., & Hacke, S. (2010). Demographischer Hintergrund und Berufsmotivation angehender Primarstufenlehrkräfte im internationalen Vergleich. In S. Blömeke, G. Kaiser, & R. Lehmann (Eds.), TEDS-M 2008 – Professionelle Kompetenz und Lerngelegenheiten angehender Primarstufenlehrkräfte im internationalen Vergleich (pp. 131–168). Münster: Waxmann.

Bond, T., & Fox, C. (2007). Applying the Rasch model: Fundamental measurement in the human sciences (2nd). LEA.

Brown, A., & Croudace, T. J. (2015). Scoring and estimating score precision using multidimensional IRT. In S. P. Reise & D. A. Revicki (Eds.), Handbook of Item Response Theory Modeling: Applications to Typical Performance Assessment (pp. 307–333). Taylor & Francis.

Bruckmann, Ch., Glutsch, N., Pohl, Th., Hanke, P., & König, J. (2019). Notwendiges Professionswissen für den basalen Lese- und Schreibunterricht aus der Sicht von Experten und Expertinnen der Lehrerausbildung. Lehrerbildung auf dem Prüfstand, 12(1), 5–18.

Brügelmann, H., & Brinkmann, E. (1998). Die Schrift erfinden – Beobachtungshilfen und methodische Ideen für einen offenen Anfangsunterricht im Lesen und Schreiben. Lengwil: Libelle.

Budde, M., Riegler, S., & Wieprächtiger-Geppert, M. (2012). Sprachdidaktik. Akademie.

Bukova-Güzel, E. (2010). An investigation of pre-service mathematics teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge, using solid objects. Scientific Research and Essays, 5, 1872–1880.

Carlisle, J. F., Correnti, R., Phelps, G., & Zeng, Ji. (2009). Exploration of the contribution of teachersʼ knowledge about reading to their students’ improvement in reading. Reading and Writing, 22, 457–486.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155.

Corvacho del Toro, Irene M. (2013). Fachwissen von Grundschullehrkräften. Schriften aus der Fakultät Humanwissenschaften der Universität Bamberg, Vol. 13. Bamberg.

de Ayala, R. J. (1995). An investigation of the standard errors of expected a posteriori ability estimates. American Educational Research Association, 4–43.

Darling-Hammond, L., & Bransford, J. (2007). Preparing teachers for a changing world: What teachers should learn and be able to do. John Wiley & Sons.

Depaepe, F., & König, J. (2018). General pedagogical knowledge, selfefficacy and instructional practice: Disentangling their relationship in pre-service teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 69, 177–190.

European Commission. (2013). Supporting teacher competence development for better learning outcomes. European Commission Education and Training UE.

Evens, M., Elen, J., Larmuseau, C., & Depaepe, F. (2018). Promoting the development of teacher professional knowledge: Integrating content and pedagogy in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 75, 244–258.

Freeman, D. (2002). The hidden side of the work: Teacher knowledge and learning to teach – A perspective from north American educational research on Teacher education in English language teaching. Language Teaching, 35(1), 1–13.

Funke, R. (2014). Erstunterricht nach der Methode Lesen durch Schreiben und Ergebnisse schriftsprachlichen Lernens – Eine metaanalytische Bestandsaufnahme. Didaktik Deutsch, 19(36), 21–41.

Gitomer, D. H., & Zisk, R. C. (2015). Knowing what teachers know. Review of Research in Education, 39, 1–53.

Grossman, P. L. (1990). The making of a teacher: Teacher knowledge and teacher education. Teachers College Press.

Grossman, P., & McDonald, M. (2008). Back to the future: Directions for research in teaching and teacher education. American Educational Research Journal, 45(1), 184–205.

Grossman, P. L., & Richert, A. E. (1988). Unacknowledged knowledge growth: A re-examination of the effects of teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 4, 53–62.

Hanke, P., & Pohl, T. h. (2020). Deutsch (Primarstufe) in der Lehrerinnen- und Lehrerbildung. Bestandsaufnahme und Perspektiven. In C. Cramer, J. König, M. Rothland, & S. Blömeke (Hrsg.), Handbuch Lehrerinnen- und Lehrerbildung. Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt/UTB, 402–409.

Hill, H. C., Rowan, B., & Ball, D. L. (2005). Effects of teachers’ mathematical knowledge for teaching on student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 42(2), 371–406.

Jagemann, S. (2018). Schriftsystematisches Professionswissen. Neuralgische Punkte und ein Vorschlag zur Modellierung. In S. Riegler, & S. Weinhold (Eds.), Rechtschreiben unterrichten (pp. 13–28). Berlin: Schmidt.

Jones, V. (2006). How do teachers learn to be effective classroom managers? In C. M. Evertson & C. S. Weinstein (Eds.), Handbook of classroom management: Research, practice, and contemporary issues (pp. 887–907). LEA.

Kaiser, G., & König, J. (2019). Competence measurement in (Mathematics) teacher education and beyond: implications for policy. Higher Education Policy, 32, 597–615.

KMK (2004a). Bildungsstandards im Fach Deutsch für den Primarbereich (Jahrgangsstufe 4). Bonn: KMK.

KMK (2004b/2019). Standards für die Lehrerbildung: Bildungswissenschaften. Bonn: KMK.

KMK (2008/2019). Ländergemeinsame inhaltliche Anforderungen für die Fachwissenschaften und Fachdidaktiken in der Lehrerbildung. Bonn: KMK.

König, J. (2014). Designing an international instrument to assess teachers’ general pedagogical knowledge (GPK): review of studies, considerations, and recommendations. Paris: OECD.

König, J., & Kramer, C. (2016). Teacher professional knowledge and classroom management: On the relation of general pedagogical knowledge (GPK) and classroom management expertise (CME). ZDM, 48(1), 139–151.

König, J., & Bremerich-Vos, A. (2020). Deutschdidaktisches Wissen angehender Sekundarstufenlehrkräfte. Testkonstruktion und Validierung. Diagnostica, 66(2), 93–109.

König, J., Blömeke, S., Jentsch, A., Schlesinger, L., Felske, C., Musekamp, F., & Kaiser, G. (2021). The links between pedagogical competence, instructional quality, and mathematics achievement in the lower secondary classroom. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 107, 189–212.

König, J., Blömeke, S., Paine, L., Schmidt, B., & Hsieh, F-J. (2011). General pedagogical knowledge of future middle school teachers. On the complex ecology of teacher education in the United States, Germany, and Taiwan. Journal of Teacher Education, 62(2), 188–201.

König, J., Lammerding, S., Nold, G., Rohde, A., Strauß, S., & Tachtsoglou, S. (2016). Teachers’ professional knowledge for teaching english as a foreign language: assessing the outcomes of teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 67(4), 320–337.

König, J., Bremerich-Vos, A., Buchholtz, C., Lammerding, S., Strauß, S., Fladung, I., & Schleiffer, C. (2017). Modelling and validating the learning opportunities of preservice language teachers: On the key components of the curriculum for teacher education. European Journal of Teacher Education, 40(3), 394–412.

König, J., & Pflanzl, B. (2016). Is teacher knowledge associated with performance? On the relationship between teachers' general pedagogical knowledge and instructional quality. European Journal of Teacher Education, 39(4), 419–436.

Krauss, S., Brunner, M., Kunter, M., Baumert, J., Blum, W., Neubrand, M., & Jordan, A. (2008). Pedagogical content knowledge and content knowledge of secondary mathematics teachers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(3), 716–725.

Krauss, S., Lindl, A., Schilcher, A., Fricke, M., Göhring, A., & Hofmann, B. (Eds.). (2017). FALKO: Fachspezifische Lehrerkompetenzen: Konzeption von Professionswissenstests in den Fächern Deutsch, Englisch, Latein, Physik, Musik, Evangelische Religion und Pädagogik. Münster: Waxmann.

Kucirkova, N., Snow, C. E., Grøver, V., & McBride, C. (Eds.). (2017). The Routledge international handbook of early literacy education: A contemporary guide to literacy teaching and interventions in a global context. Taylor & Francis.

Liu, S., & Phelps, G. (2020). Does teacher learning last? Understanding how much teachers retain their knowledge after professional development. Journal of Teacher Education, 71(5), 537–550.

Maas, U. (2015). Laute und Buchstaben – zu den phonographischen Grundlagen des Schrifterwerbs. C. Röber & H. Olfert (Eds.) Schriftsprach- und Orthographieerwerb. Erstlesen, Erstschreiben (pp. 113–139). Baltmannsweiler: Schneider.

Maulana, R., Helms-Lorenz, M., & Van de Grift, W. (2017). Validating a model of effective teaching behaviour of pre-service teachers. Teachers and Teaching, 23(4), 471–493.

Meng, X. L., Rosenthal, R., & Rubin, D. B. (1992). Comparing correlated correlation coefficients. Psychological Bulletin, 111(1), 172–175.

Mullis, I. V., & Martin, M. O. (2019). PIRLS 2021 assessment frameworks. International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement.

Munby, H., Russell, T., & Martin, A. K. (2001). Teachers’ knowledge and how it develops. Handbook of Research on Teaching, 4, 877–904.

Neuman, S. B., & Dickinson, D. K. (Eds.). (2003). Handbook of early literacy research (Vol. 1). Guilford Press.

OECD. (2014). PISA 2012 results: what students know and can do. Student Performance in Mathematics, Reading, and Science, Vol 1. Paris: OECD.

Reichen, J. (2008). Lesen durch Schreiben: Lesenlernen ohne Leseunterricht. Grundschulunterricht Deutsch, 2, 4–8.

Riegler, S., Wieprächtiger-Geppert, M. (2016). Konzeptneutral und unterrichtsnah. Ein Instrument zur Erfassung des Professionswissens zu Orthographie und Orthographieerwerb. In H. Zimmermann & A. Peyer (Eds.), Wissen und Normen. Facetten professioneller Kompetenz von Deutschlehrkräften (pp. 199–219). Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Röber, C. (2009). Die Leistungen der Kinder beim Lesen- und Schreibenlernen – Grundlagen der Silbenanalytischen Methode. Baltmannsweiler: Schneider.

Rutsch, J., & Dörfler, T. (2017). Vignettentest zur Erfassung des fachdidaktischen Wissens im Leseunterricht bei angehenden Lehrkräften. Diagnostica, 64, 2–13.

Sadler, P. M., Sonnert, G., Coyle, H. P., Cook-Smith, N., & Miller, J. L. (2013). The influence of teachers’ knowledge on student learning in middle school physical science classrooms. American Educational Research Journal, 50(5), 1020–1049.

Schmidt, W. H., Tatto, M. T., Bankov, K., Blömeke, S., Cedillo, T., Cogan, L., et al. (2007). The preparation gap: Teacher education for middle school mathematics in six countries – Mathematics teaching in the 21st century (MT21 Report).

Schoenfeld, A. H. (1998). Toward a theory of teaching-in-context. Issues in Education, 4(1), 1–94.

Shulman, L. S. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1–22.

Stahns, R., Rieser, S., & Hußmann, A. (2020). Können Viertklässlerinnen und Viertklässer Unterrichtsqualität valide einschätzen? Ergebnisse zum Fach Deutsch. Unterrichtswissenschaft, 1–20.

Stigler, J. W., & Miller, K. F. (2018). Expertise and expert performance in teaching. In A. Ericsson, R. R. Hoffman, A. Kozbelt, & A. M. Williams (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance (2nd edition, pp. 431–452). Cambridge University Press.

Tatto, M. T., Schwille, J., & Senk, S. L. (2008). Teacher education and development study in mathematics (TEDS-M). IEA.

Tatto, M. T., Schwille, J., Senk, S., Ingvarson, L., Rowley, G., Peck, R., et al. (2012). Policy, practice, and readiness to teach primary and secondary mathematics in 17 countries. Findings from the IEA teacher education and development study in mathematics (TEDS-M).

Woolfolk Hoy, A., Davis, H., & Pape, S. J. (2006). Teacher knowledge and beliefs. Handbook of Educational Psychology, 2, 715–738.

Wright, B. D., & Linacre, J. M. (1994). Reasonable mean-square fit values. Rasch Measurement Transactions, 8(3), 370.

Wu, M., Adams, R. J., & Wilson, M. (1997). Multilevel item response models: An approach to errors in variables regression. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 22(1), 47–76.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Moreover, this work is part of a larger project called Zukunftsstrategie Lehrer*innenbildung Köln (ZuS): Inklusion und Heterogenität gestalten. ZuS is part of the Qualitätsoffensive Lehrerbildung (Quality Initiative for Initial Teacher Education), a joint initiative of the Federal Government and the Länder which aims to improve the quality of teacher training. The programme is funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research [grant number 01JA1515 and 01JA1815].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

König, J., Hanke, P., Glutsch, N. et al. Teachers’ professional knowledge for teaching early literacy: conceptualization, measurement, and validation. Educ Asse Eval Acc 34, 483–507 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-022-09393-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-022-09393-z