Abstract

Can citizens heed factual information, even when such information challenges their partisan and ideological attachments? The “backfire effect,” described by Nyhan and Reifler (Polit Behav 32(2):303–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9112-2, 2010), says no: rather than simply ignoring factual information, presenting respondents with facts can compound their ignorance. In their study, conservatives presented with factual information about the absence of Weapons of Mass Destruction in Iraq became more convinced that such weapons had been found. The present paper presents results from five experiments in which we enrolled more than 10,100 subjects and tested 52 issues of potential backfire. Across all experiments, we found no corrections capable of triggering backfire, despite testing precisely the kinds of polarized issues where backfire should be expected. Evidence of factual backfire is far more tenuous than prior research suggests. By and large, citizens heed factual information, even when such information challenges their ideological commitments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Google News search for the “backfire”, “backlash”, or “boomerang” effect and the names of Nyhan or Reifler returns over 300 unique articles. The 2010 backfire paper has also enjoyed remarkable academic attention. Among all papers printed in Political Behavior in the last 10 years, “When Corrections Fail” has been cited four times as much as the next most cited paper.

In this way, the apparent difficulty in making one’s policy preferences fit with one’s factual attitudes is redolent of Americans’ struggle to have their policy preferences fit with each other—what Converse (1964) famously described as poor “constraint.”

To avoid the possibility of unintended panel conditioning, we excluded any Turk worker which had been participated in a prior study.

The choice of the OLS model, and the specific measures for agreement, ideology, and correction, were chosen to be consistent with Nyhan and Jason (2010).

This relationship persisted if we compare respondents along the partisan scale. This result is described in Sect. A.14.1 on p. xxvi.

Of course, the attitudinal consequence of this fact remains at a respondent’s discretion, but functional democratic competence would seem to require that voters adopt a common set of basic political facts.

Three articles were taken from study 3: the original Bush WMD article, the piece by Speaker Paul Ryan criticizing President Obama’s policy toward abortion, and Secretary Hillary Clinton claim that twice as many Americans were employed in solar than in the oil industry. Three novel mock articles were also provided: Senator Sanders claiming that the EPA had found fracking was responsible for polluting water supplies, Donald Trump claiming that his tax cut plan would grow federal tax receipts, and Trump claiming that the true unemployment rate was actually higher than 30%. These mock articles can be read in Sect. A.9, which can be found in the appendix on p. xvi. The items can be read in Table 11 on p. xxiii.

For this study, President Obama, Secretary Clinton, and Senator Sanders are deemed liberal speakers, and President Trump and President Bush are deemed conservative speakers.

Coppock and McClellan (2017) report an extensive test of the Lucid sample, comparing it to Turk, the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey, and the American National Election Study’s (ANES) face to face and online samples. Treating the ANES face-to-face sample as the “gold standard”, the Lucid sample is more psychologically similar to the ANES than the Turk sample on the Big-5 personality battery, and better matches the political knowledge and conservatism in the ANES. Coppock and McClellan also test the Lucid sample’s ability to recover treatment effects in canonical social psychology experiments. Both Lucid and Turk samples recover the same framing effect observed the General Social Survey (a massive face-to-face survey instrument), improving the appetite for public spending when it is described as “assistance to the poor” or “caring for the poor” rather than “welfare.” Both Lucid and Turk feature the same framing effect underpinning prospect theory [(the famous Tversky and Kahneman (1983) finding which shows risk tolerance is affected by framing possible outcomes as gains or losses.] Both Lucid and Turk recover indistinguishable experimental effects as observed in Hiscox (2006) in framing attitudes about free trade. Most importantly for this study, the one failed replication was on rumor corrections in the aforementioned Berinsky paper (2017), where Lucid respondents were unusually resistant to corrective information. This suggests that the Lucid sample is at least a comparably demanding sample in which to test factual adherence.

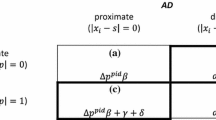

In brief—a weak correction might inadvertently advertise the weakness of the corrective case, or a strong correction might have more obvious factual implications, and therefore inspire more forceful counterargument.

These respondents were recruited on Mechanical Turk.

As a robustness check—there was no significant relationship between ideology and perceived accordance, for any of the tested pairs.

It’s instructive to consider those statement/correction pairs at either end of this spectrum. The statement by Senator Ted Cruz about the incidence of violence targeted at law enforcement, described above, was judged the most proximate correction. At the other end of this continuum is the 2012 claim by Congressman Paul Ryan that “Obama stands for an absolute, unqualified right to abortion—at any time, under any circumstances, and paid for by taxpayers” and the correction that “The number of abortions steadily declined during President Obama’s first term, with fewer abortions in 2012 than any year since 1973.” While Cruz makes a precise claim about the change in the incidence of killings of police officers, Ryan’s statements merely suggested a spike in the incidence of abortion.

An example of a proximate correction is Representative Gutiérrez’s promise that President Obama would be the “champion...[of the] undocumented” paired with the evidence that Obama was a prodigious deporter of these residents. This correction/statement pair was scored 81.7 on a 100-pt scale of accordance.

An example of a distant correction is Governor Romney’s description of the United States using “a credit card ...issued by the Bank of China” and the correction that China holds about 15% of US debt. This correction/statement pair was scored 47.2.

Contra our evidence in “Does Counterargument Explain Our Pattern of Findings?” section.

References

Barnes, L., Feller, A., Haselswerdt, J., & Porter, E. (2016). Information and preferences over redistributive policy: A field experiment. Working Paper.

Berinsky, A. J. (2017). Rumors and health care reform: Experiments in political misinformation. British Journal of Political Science, 47(2), 241–262. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123415000186.

Brock, T. C. (1967). Communication discrepancy and intent to persuade as determinants of counterargument production. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 3(3), 296–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(67)90031-5.

Bullock, J. G., Gerber, A. S., Hill, S. J., & Huber, G. A. (2013). Partisan bias in factual beliefs about politics. Working Paper, March 2013, pp. 1–73. https://doi.org/10.1561/100.00014074.

Cacioppo, J. T., Petty, R. E., & Morris, K. J. (1983). Effects of need for cognition on message evaluation, recall, and persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(4), 805–818. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.45.4.805.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., & Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American Voter. New York: Wiley.

Carmines, E., & Stimson, J. (1980). The two faces of issue voting. American Political Science Review, 74(1), 78–91. https://doi.org/10.2307/1955648.

Chong, D., & Druckman, J. (2013). Counterframing effects. The Journal of Politics, 75(1), 1–16. Retrieved from http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1017/S0022381612000837.

Cochran, W. G., & Cox, G. M. (1957). Experimental designs. New York: Wiley.

Conover, P. J., & Feldman, S. (1981). The origins and meaning of liberal/conservative self-identifications. American Journal of Political Science, 25(4), 617. https://doi.org/10.2307/2110756.

Converse, P. E. (2006). The nature of belief systems in mass publics (1964). Critical Review: A Journal of Politics and Society, 18(1–3), 1–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/08913810608443650.

Coppock, A., & Mcclellan, O. A. (2017). Validating the demographic, political, psychological, and experimental results obtained from a new source of online survey respondents. Retrieved from http://alexandercoppock.com/papers/CM_lucid.pdf.

Fishkin, J. S., & Luskin, R. C. (2005). Experimenting with a democratic ideal: Deliberative polling and public opinion. Acta Politica, 40, 284–298. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500121.

Fowler, A., & Montagnes, B. P. (2015). College football, elections, and false-positive results in observational research. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(45), 13800–13804.

Gerber, A., & Green, D. (1999). Misperceptions about perceptual bias. Annual Review of Political Science, 2, 189–210. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.2.1.189.

Gollust, S. E., Lantz, P. M., & Ubel, P. A. (2009). The polarizing effect of News Media messages about the social determinants of health. Public Health, 99, 2160–2167. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.161414.

Healy, A., Malhotra, N., & Mo, C. (2010). Irrelevant events affect voters’ evaluations of government performance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(29), 12804–12809. Retrieved from http://www.pnas.org/content/107/29/12804.short.

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The Weirdest people in the world?’. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2–3), 61–135. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0999152X.

Hiscox, M. J. (2006). Through a glass and darkly: Attitudes toward international trade and the curious effects of issue framing. International Organization. Cambridge University Press. http://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818306060255.

Howell, W. G., & West, M. R. (2009). Educating the public. Education Next, 9(3), 40–47.

Jost, J. T., Nosek, B. A., & Gosling, S. D. (2008). Ideology: Its resurgence in social, personality, and political psychology. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(2), 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00070.x.

Kahan, D. M., Peters, E., Dawson, E. C., & Slovic, P. (2017). Motivated numeracy and enlightened selfgovernment. Behavioural Public Policy, 1(01), 54–86. https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2016.2.

Kaplan, J. T., Gimbel, S. I., & Harris, S. (2016). Neural correlates of maintaining one’s political beliefs in the face of counterevidence. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 39589. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep39589.

Kuklinski, J. H., & Quirk, P. J. (2000). Reconsidering the rational public: Cognition, heuristics, and mass opinion. In Elements of reason: Cognition, choice and the bounds of rationality (pp. 153–182).

Lippman, W. (1922). Public opinion. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company.

Lord, C., Ross, L., & Lepper, M. (1979). Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. Journal of Personality and Social. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/psp/37/11/2098/.

Mondak, J. J. (1993). Public opinion and heuristic processing of source cues. Political Behavior, 15(2), 167–192. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/586448.

Mondak, J. J. (1994). Policy legitimacy and the Supreme Court: The sources and contexts of legitimation. Political Research Quarterly, 47(3), 675. https://doi.org/10.2307/448848.

Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2010). When corrections fail: The persistence of political misperceptions. Political Behavior, 32(2), 303–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9112-2.

Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2017). Answering on cue? How corrective information can produce social desirability bias when racial differences are salient. Retrieved from http://www.dartmouth.edu/~nyhan/obama-muslim.pdf.

Nyhan, B., Reifler, J., Edelman, C., Passo, W., Banks, A., Boston, E., et al. (2015). Answering on cue?. Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College.

Nyhan, B., Reifler, J., Richey, S., & Freed, G. L. (2014). Effective messages in vaccine promotion: A randomized trial. Pediatrics, 133(4), e835–e842. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-2365.

Nyhan, B., Reifler, J., & Ubel, P. A. (2013). The hazards of correcting myths about health care reform. Medical Care, 51(2), 127–132. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e318279486b.

Prior, M. (2007). Is partisan bias in perceptions of objective conditions real? The effect of an accuracy incentive on the stated beliefs of partisans. In Annual conference of the Midwestern Political Science Association.

Prior, M., Sood, G., & Khanna, K. (2015). The impact of accuracy incentives on partisan bias in reports of economic perceptions. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 10, 489–518. https://doi.org/10.1561/100.00014127.

Redlawsk, D. P. (2002). Hot cognition or cool consideration? Testing the effects of motivated reasoning on political decision making. The Journal of Politics, 64(4), 1021–1044. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2508.00161.

Sanna, L. J., Schwarz, N., & Stocker, S. (2002). When debiasing backfires: Accessible content and accessibility experiences in debiasing hindsight. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning Memory and Cognition, 28(3), 497–502. https://doi.org/10.1037//0278-7393.28.3.497

Schaffner, B. F., & Roche, C. (2017). Misinformation and motivated reasoning: Responses to economic news in a politicized environment. Public Opinion Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfw043.

Skurnik, I., Yoon, C., Park, D. C., & Schwarz, N. (2005). How warnings about false claims become recommendations. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(4), 713–724. https://doi.org/10.1086/426605.

Sniderman, P. M., Brody, R. A., & Tetlock, P. E. (1993). Reasoning and choice: Explorations in political psychology. Cambridge University Press.

Stroud, N. J. (2008). Media use and political predispositions: Revisiting the concept of selective exposure. Political Behavior, 30, 341–366. https://doi.org/10.2307/40213321.

Swire, B., Berinsky, A. J., Lewandowsky, S., & Ecker, U. K. H. (2017). Processing political misinformation: Comprehending the Trump phenomenon. Royal Society Open Science, 4(3), 160802. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.160802.

Taber, C. S., & Lodge, M. (2006). Motivated specticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. Political Science, 50(3), 755–769. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00214.x.

Thorson, E. (2015). Belief echoes: The persistent effects of corrected misinformation. Political Communication, 46(9), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2015.1102187.

Trevors, G. J., Muis, K. R., Pekrun, R., Sinatra, G. M., & Winne, P. H. (2016). Identity and epistemic emotions during knowledge revision: A potential account for the backfire effect. Discourse Processes. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2015.1136507.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1983). Extensional versus intuititive reasoning: The conjuction fallacy in probability judgment. Psychological Review, 90(4), 293–315. http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/rev/90/4/293/.

Wood, T., & Oliver, E. (2012). Toward a more reliable implementation of ideology in measures of public opinion. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76(4), 636–662. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfs045.

Zaller, J. R. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Leticia Bode, John Brehm, DJ Flynn, Jim Gimpel, Don Green, Will Howell, David Kirby, Michael Neblo, Brendan Nyhan, Gaurav Sood, and the participants at the Center for Stategic Initiatives workshop. Research support was generously furnished by the Cato Institute, and we owe a special debt of gratitude to Emily Ekins and David Kirby. All remaining errors are the responsibility of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

All figures and tables in this paper can be replicated with the syntax available at the Political Behavior dataverse: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/AGRX5U

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wood, T., Porter, E. The Elusive Backfire Effect: Mass Attitudes’ Steadfast Factual Adherence. Polit Behav 41, 135–163 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-9443-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-9443-y