Abstract

In this paper, we examine the effect of US-imposed sanctions on the civil liberties of the targeted countries for the 1972–2014 period. To deal with the problem of selection and to control for the pre-sanction dynamics, we use a potential outcomes framework, which does not rely on the selection of matching variables and has the further advantage of uncovering the effect of the treatment on the outcome variable over time. What we find is that sanctions result in a decline in civil liberties, measured either by the Freedom House civil liberties index or by the Cingranelli and Richards empowerment rights index. The results are robust across various specifications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Just before the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, the Athenian empire levied sanctions on the city of Megara, excluding Megarians from the empire’s market and harbors. For many scholars, the economic consequences of those sanctions were a decisive factor in the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War (Brunt 1951).

The recent debate over the appropriateness of imposing sanctions in order to destabilize the Maduro regime in Venezuela is suggestive: proponents of the use of sanctions claim that immiserizing the general population will destabilize the regime and eventually improve the conditions in the country. On the other hand, opponents consider the measures to be ineffective since they give the regime the opportunity to use propaganda and repression to strengthen its position further.

With that in mind, our baseline analysis includes a general category of sanction episodes and not only those with the goal of reducing repression and destabilizing the targeted regime.

To examine the robustness of our results, we also examine UN-imposed sanctions as well as sanctions imposed by all states.

Choi and James (2016) provide evidence that US military interventions also are primarily prompted by the same reason.

Specifically, Peksen and Drury (2009, 2010) find that sanctions have a negative effect on the level of democracy, as measured by the Freedom House index of civil and political liberties, which in the long run is equivalent to approximately a one-point decline in the index on its 1–7 cardinal scale. Peksen (2009) and Wood (2008) find similar effects using an index of respect for human rights and an index of political terror, as dependent variables, respectively.

Nooruddin (2002) deals with the problem of selection by estimating a selection model in the spirit of Heckman (1979). Similarly, Jing et al. (2003) estimate a two-stage model wherein sanctions are imposed according to an endogenous political process and the model therefore controls effectively for both the selection and the confounding factors problem. Here we follow another approach, mimicking randomization.

Kaempfer et al. (2004) consider a policy of using the sanctions to target directly the means of repression as more effective, since it increases the price of repression and thus destabilizes the regime.

The countries in our sample are listed in the “Appendix”.

The political liberties ideals involve, as Gastil (1982, p. 7) points out, the “rights to participate meaningfully in the political process. In a democracy this means the right of all adults to vote and compete for public office, and for elected representatives to have a decisive vote on public policies”. Civil liberties ideals involve a series of various economic, political and civil liberties enjoyed by the citizens of the country, such as freedom of expression and belief, association and organization rights, rule of law and personal autonomy and economic rights. Similarly, in the words of Gastil (ibid.), “Civil liberties are rights to free expression, to organize or demonstrate, as well as rights to a degree of autonomy such as is provided by freedom of religion, education, travel, and other personal rights”.

As robustness analysis, we also examine the effect of sanctions imposed by the United Nations and sanctions imposed by all states.

The United States participated in 46.5% of all sanctions imposed and issued 56.4% of all sanction threats from 1946 up to 2004.

See also Angrist and Kuersteiner (2011) for the technical details.

As country fixed effects are cancelled out when we take changes in the CL variable, no reason exists to include them at the first stage.

We can test whether significant pre-treatment dynamics exist by estimating the effect of treatment for years prior to the treatment. The figures and tables in the following section show that the estimator matches the pre-treatment dynamics, as in most cases the effect for t = − 4, …, − 1 turns out insignificant, providing evidence that the estimator removes any (pre-treatment) dynamics in the dependent variable that may be correlated with the treatment.

The weights used are calculated according to the inverse probability weighting scheme.

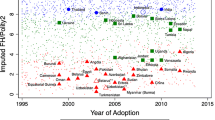

The three models discussed above rely on three basic assumptions to estimate the ATET: (i) conditional Independence, i.e., after conditioning on the covariates, the outcomes (civil liberties) are conditionally independent of the control-level potential outcome, (ii) overlap, i.e., each treated observation has a positive probability of being allocated to each treatment level and (iii) i.i.d., which in our setting rules out interactions among countries in each period. If we were to estimate the ATEs (Average Treatment Effects), those assumptions would have taken a more restrictive form, requiring both conditional independence and overlap to hold for both treatment statuses (Wooldrige 2010). For more details on the assumptions, see Imbens and Wooldridge (2009) and Angrist and Pischke (2009). To inspect visually whether the overlap assumption holds in Fig. 3 in the “Appendix”, we present the smoothed densities, using a standard Epanechnikov kernel, of the estimated propensities of receiving sanctions between the two groups. As the reader can verify, considerable overlap is found among treated and control propensities. What is more important, the control observations cover the support for all treated observations, when either the Freedom House or the empowerment rights index is used. That evidence provides support for the required overlap assumption and gives suggestive evidence in favor of our empirical strategy.

We conceive the doubly robust method as being more general, since it combines the two other methods and we rely solely on it for the robustness analysis. The associated impulse response functions for the regression adjustment and the inverse probability weighting methods are shown in the “Appendix”. The remaining results are available from the authors and are qualitatively similar to the ones presented here.

We should note that in all cases the pre-sanction dynamics are found to be either statistically or quantitatively insignificant, i.e., the coefficients for the years t = − 4, − 3, −2, − 1 are statistically insignificant or have very small values. These findings imply that countries are made comparable in terms of pre-treatment dynamics. This result remains valid in our robustness tests as well.

The finding also verifies the analysis of Kaempfer and Lowenberg (1999), who show that unilateral sanctions are more effective in reducing repression than multilateral sanctions.

We should note that in 58 out of 67 sanction episodes in our sample, the United States also participated as a primary or secondary sender.

References

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., Robinson, J. A., & Yared, P. (2009). Reevaluating the modernization hypothesis. Journal of Monetary Economics, 56(8), 1043–1058.

Acemoglu, D., Naidu, S., Restrepo, P., & Robinson, J. A. (2018). Democracy does cause growth. Journal of Political Economy (forthcoming).

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2005). Economic origins of dictatorship and democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Adam, A., & Filippaios, F. (2007). Foreign direct investment and civil liberties: A new perspective. European Journal of Political Economy, 23(4), 1038–1052.

Angrist, J. D., Jordi, O., & Kuersteiner, G. M. (2018). Semiparametric estimates of monetary policy effects: String theory revisited. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 36(3), 1–17.

Angrist, J. D., & Kuersteiner, G. M. (2011). Causal effects of monetary shocks: Semiparametric conditional independence tests with a multinomial propensity score. Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(3), 725–747.

Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J.-S. (2009). Mostly harmless ecoometrics: An empiricists companion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Barro, R. J. (1999). Determinants of democracy. Journal of Political Economy, 107(S6), S158–S183.

Bjørnskov, C., & Rode, M. (2017). Regime types and regime change: A new dataset. Working Paper, Aarhus University and Universidad de Navarra.

Brunt, P. A. (1951). The Megarian Decree. The American Journal of Philology, 72(3), 269–282.

Bueno De Mesquita, B., & Siverson, R. M. (1995). War and the survival of political leaders: A comparative study of regime types and political accountability. American Political Science Review, 89(4), 841–855.

Cheibub, J. A., Gandhi, J., & Vreeland, J. R. (2010). Democracy and dictatorship revisited. Public Choice, 143(1), 67–101.

Choi, S.-W., & James, P. (2016). Why does the United States intervene abroad? Democracy, human rights violations, and terrorism. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 60(5), 899–926.

Cingranelli, D. L., & Richards, D. L. (2010). The Cingranelli and Richards (CIRI) human rights data project. Human Rights Quarterly, 32(2), 401–424.

Cortright, D., & Lopez, G. A. (2000). The sanctions decade: Assessing UN strategies in the 1990s. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Cox, D. G., & Drury, A. C. (2006). Democratic sanctions: Connecting the democratic peace and economic sanctions. Journal of Peace Research, 43(6), 709–722.

Daponte, B. O., & Garfield, R. (2000). The effect of economic sanctions on the mortality of Iraqi children prior to the 1991 Persian Gulf War. American Journal of Public Health, 90(4), 546–552.

Denizer, C., Kaufmann, D., & Kraay, A. (2013). Good countries or good projects? Macro and micro correlates of World Bank project performance. Journal of Development Economics, 105, 288–302.

Galtung, J. (1967). On the effects of international economic sanctions, with examples from the case of Rhodesia. World Politics, 19(3), 378–416.

Gastil, R. D. (1982). Freedom in the world: Political rights and civil liberties. Westport: Greenwood Press.

Gutmann, J., Neuenkirch, M., & Neumeier, F. (2016). Precision-guided or blunt? The effects of US economic sanctions on human rights (CESifo Working Paper Series No. 229). CESifo Institute, Munich.

Heckman, J. J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47(1), 153–161.

Henderson, C. W. (1998). Population pressures and political repression. Social Sciences Quarterly, 74(2), 322–333.

Hufbauer, G. C., Schott, J. J., Elliott, K. A., & Oegg, B. (2009). Economic sanctions reconsidered. Peterson Institute for International Economics: Washington.

Huntington, S. P. (1993). The third wave: Democratization in the late twentieth century. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Imbens, G. W., & Wooldridge, J. M. (2009). Recent developments in the econometrics of program evaluation. Journal of economic literature, 47(1), 5–86.

Jing, C., Kaempfer, W. H., & Lowenberg, A. D. (2003). Instrument choice and the effectiveness of international sanctions: A simultaneous equations approach. Journal of Peace Research, 40(5), 519–535.

Kaempfer, W. H., & Lowenberg, A. D. (1988). The theory of international economic sanctions: A public choice approach. American Economic Review, 78(4), 786–793.

Kaempfer, W. H., & Lowenberg, A. D. (1999). Unilateral versus multilateral international sanctions: A public choice perspective. International Studies Quarterly, 43(1), 37–58.

Kaempfer, W. H., Lowenberg, A. D., & Mertens, W. (2004). International economic sanctions against a dictator. Economics and Politics, 16(1), 29–52.

Kline, P. (2011). Oaxaca-Blinder as a reweighting estimator. The American Economic Review, 101(3), 532–537.

Knutsen, C. H. (2015). Why democracies outgrow autocracies in the long run: Civil liberties, information flows and technological change. Kyklos, 68(3), 357–384.

Lektzian, D., & Souva, M. (2001). Institutions and international cooperation: An event history analysis of the effects of economic sanctions. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 45(1), 61–79.

Lektzian, D., & Souva, M. (2003). The economic peace between democracies: Economic sanctions and domestic institutions. Journal of Peace Research, 40(6), 641–660.

Levitsky, S., & Way, L. A. (2010). Competitive authoritarianism: Hybrid regimes after the Cold War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lipset, S. M. (1959). Some social requisites of democracy: Economic development and political legitimacy. American Political Science Review, 53(01), 69–105.

Morgan, T. C., Bapat, N., & Kobayashi, Y. (2014). Threat and imposition of economic sanctions 1945–2005: Updating the TIES dataset. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 31(5), 541–558.

Neuenkirch, M., & Neumeier, F. (2016). The impact of US sanctions on poverty. Journal of Development Economics, 121, 110–119.

Nooruddin, I. (2002). Modeling selection bias in studies of sanctions efficacy. International Interactions, 28(1), 59–75.

Peksen, D. (2009). Better or worse? The effect of economic sanctions on human rights. Journal of Peace Research, 46(1), 59–77.

Peksen, D., & Drury, A. C. (2009). Economic sanctions and political repression: Assessing the impact of coercive diplomacy on political freedoms. Human Rights Review, 10(3), 393–411.

Peksen, D., & Drury, A. C. (2010). Coercive or corrosive: The negative impact of economic sanctions on democracy. International Interactions, 36(3), 240–264.

Poe, S. C., Neal Tate, C., & Keith, L. C. (1999). Repression of the human right to personal integrity revisited: A global cross-national study covering the years 1976–1993. International Studies Quarterly, 43(2), 291–313.

Services, H. H. (2001). Overview and compilation of US trade statutes. Washington: US Government Printing Office.

Weeks, J. L. P. (2014). Dictators at war and peace. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Wintrobe, R. (1998). The political economy of dictatorship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wood, R. M. (2008). A hand upon the throat of the nation: Economic sanctions and state repression, 1976–2001. International Studies Quarterly, 52(3), 489–513.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Nikos Mylonidis, Thomas Moutos, Mario Gilli, Stamatia Ftergioti, Fabio Antoniou, Mohammad Reza Farzaneganm, Paul Schaudt, participants at the 11th CESifo Workshop on Political Economy, participants at the 2nd PEDD conference, and seminar participants at the University of Ioannina and University of Patras and two anonymous referees for all their valuable comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix

See Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 and Table 8.

Smoothed density for the propensity to receive sanctions. Notes The figures plot the smoothed density of the estimated propensities to receive sanctions. The top figure uses the Freedom House civil liberties index and the bottom figure the empowerment rights index. The black line plots the density for countries that received sanctions, while the gray line plots the density for the control countries, which have not received sanctions. The densities are smoothed using a standard Epanechnikov kernel

Country list

Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, Argentina, Armenia, Australia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Belarus, Belgium, Benin, Bhutan, Bolivia, Bosnia, Botswana, Brazil, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cambodia, Cameroon, Canada, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Chile, China, Colombia, Comoros, Congo Brazzaville, Congo Kinshasa, Costa Rica, Croatia, Cuba, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Djibouti, Dominican Republic, East Timor, Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea Estonia, Ethiopia, Fiji, Finland, France, Gabon, Gambia, Georgia, Germany, Ghana, Greece, Guatemala, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Ivory Coast, Jamaica, Japan, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Korea North, Korea South, Kosovo, Kuwait, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Latvia, Lebanon, Lesotho, Liberia, Libya, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Madagascar, Malawi, Malaysia, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mexico, Moldova, Mongolia, Montenegro, Morocco, Mozambique, Myanmar, Namibia, Nepal, Netherlands, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Niger, Nigeria, Norway, Oman, Pakistan, Panama, Papua New Guinea, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Qatar, Romania, Russia, Rwanda, Saudi Arabia, Senegal, Serbia, Sierra Leone, Singapore, Slovenia, Solomon Islands, Somalia, South Africa, Spain, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Suriname, Swaziland, Sweden, Switzerland, Syria, Taiwan, Tajikistan, Tanzania, Thailand, Togo, Tunisia, Turkey, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates, Uganda, Ukraine, United Kingdom, Uruguay, Uzbekistan, Venezuela, Vietnam, Yemen, Yugoslavia, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Adam, A., Tsarsitalidou, S. Do sanctions lead to a decline in civil liberties?. Public Choice 180, 191–215 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-018-00628-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-018-00628-6