Abstract

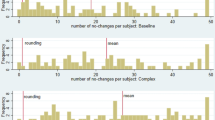

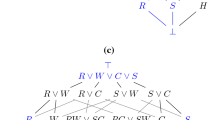

Forgetting can be a salient source of uncertainty for subjective beliefs, confidence, and ambiguity attitudes. To investigate this, we run several experiments where people bet on propositions (facts) that they cannot recall with certainty. We use betting preferences to infer subjects’ revealed beliefs and their revealed confidence in these beliefs. Forgetting is induced via interference tasks and time delays (up to one year). We observe a natural memory decay pattern where beliefs become less accurate and confidence is reduced as well. Moreover, we find a form of comparative ignorance where subjects are more ambiguity averse when they cannot recall the truth rather than never having learnt it. In a different vein, we identify an overconfidence pattern: on average, subjects overpay for bets on propositions that they believe in, but underpay for the opposite bets. We formulate a two-signal behavioral model of forgetting that generates all of these patterns. It suggests new testable hypotheses that are confirmed by our data.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

These numbers are reported at http://www.innocenceproject.org/dna-exonerations-in-the-united-states/ for the time period of 1989–2018.

In every one of the DNA exoneration cases involving eyewitness misidentification examined by Garrett (2011), witnesses who mistakenly identified innocent defendants did so with high confidence in a court of law.

For example, agents behave as if they forget fees on credit card accounts (Agarwal et al. 2013), the operating costs of mutual funds (Barber et al. 2005), whether or not sales tax is included in stated prices (Chetty et al. 2009) etc. Note that binary bets in our experiments are analogous to Arrow securities used in the Arrow-Debreu equilibria.

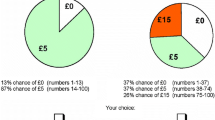

A coarse BDM procedure such as this has an advantage over a fine procedure in that it is easier for subjects to understand. The disadvantage is that it has less statistical power with regard to detecting small differences in valuations.

The comparison between L and PF is within-subject, whereas comparing CF with L or PF is within-subject with attrition, and comparing CF with other treatments is between-subjects. While each subject has repeated measures, for statistical tests, unless otherwise stated, each subject contributes one observation consisting of his/her average/proportion across proposition pairs (A,¬A). We report p-values for the Wilcoxon Sign-Rank test unless otherwise stated.

Indeterminate beliefs in stage L are rare and harder to explain exclusively by complete forgetting.

References

Agarwal, S., Driscoll, J.C., Gabaix, X., Laibson, D. (2013). Learning in the credit card market. Mimeo, SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=109162.

Baliga, S., & Ely, J. (2011). Mnemonomics: The sunk cost fallacy as a memory kludge. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 3, 35–67.

Barber, B., Odean, T., Zheng, L. (2005). Out of sight, out of mind: The effects of expenses on mutual fund flows. The Journal of Business, 78, 2095–2120.

Battigalli, P. (1997). Dynamic consistency and imperfect recall. Games and Economic Behavior, 20(1), 31–50.

Blavatskyy, P. (2009). Betting on own knowledge: Experimental test of overconfidence. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 38, 39–49.

Brewer, N., & Burke, A. (2002). Effects of testimonial inconsistencies. Law and Human Behavior, 30, 31–50.

Brown, G., Neath, I., Chater, N. (2007). A temporal ratio model of memory. Psychological Review, 114(3), 539–576.

Camerer, C., & Lovallo, D. (1999). Overconfidence and excess entry: An experimental approach. American Economic Review, 89(1), 306–318.

Chetty, R., Looney, A., Kroft, K. (2009). Salience and taxation: Theory and evidence. American Economic Review, 99, 1145–1177.

Costello, F., & Watts, P. (2014). Surprisingly rational: Probability theory plus noise explains biases in judgment. Psychological Review, 121, 463–480.

de Finetti, B. (1937). La prévision: ses lois logiques, ses sources subjectives. Annales de l’Institute Henri Poincare, 7, 1–68. Translated and reprinted in Kyburg and Smokler, 1964.

Erev, I., Wallsten, T., Budescu, D. (1994). Simultaneous over- and underconfidence: The role of error in judgment processes. Psychological Review, 101, 519–527.

Ericson, K. (2011). Forgetting we forget: Overconfidence and memory. Journal of the European Economic Association, 9(1), 43–60.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). Z-tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10(2), 171–178.

Fischhoff, B., Slovic, P., Lichtenstein, S. (1977). Knowing with certainty: The appropriateness of extreme confidence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 3(4), 552–564.

Fox, C., & Tversky, A. (1995). Ambiguity aversion and comparative ignorance. Quaterly Journal of Economics, 110, 585–603.

Froehle, C., & White, D. (2014). Interruption and forgetting in knowledge-intensive service environments. Production and Operations Management, 23(4), 704–722.

Garrett, B. (2011). Convicting the Innocent. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Heath, C., & Tversky, A. (1991). Preference and belief: Ambiguity and competence in choice under uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 4(1), 5–28.

Hirshleifer, D., & Welch, I. (2002). An economic approach to the psychology of change: Amnesia, inertia, and impulsiveness. Journal of Economic Management Strategy, 11(3), 379–421.

Hoelzl, E., & Rustichini, A. (2005). Overconfident: Do you put your money on it? The Economic Journal, 115(503), 305–318.

Keren, G. (1991). Calibration and probability judgements: Conceptual and methodological issues. Acta Psychologica, 77, 217–273.

Kirchler, E., & Maciejovsky, B. (2002). Simultaneous over- and underconfidence: Evidence from experimental asset markets. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 25, 65–85.

Lichtenstein, S., & Fischhoff, B. (1977). Do those who know more also know more about how much they know? Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 20(2), 159–183.

Lindsay, R., Wells, G., Rumpel, C. (1981). Can people detect eyewitnesses identification accuracy within and across situations? Journal of Applied Psychology, 66, 79–89.

McKenna, S., & Glendon, I. (1985). Occupational first aid training: Decay in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (cpr) skills. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 58(2), 109–117.

Moore, D., & Healy, P. (2008). The trouble with overconfidence. Psychological Review, 115(2), 502–517.

Mullainathan, S. (2002). A memory-based model of bounded rationality. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(3), 735–774.

Piccione, M., & Rubinstein, A. (1997a). The absent-minded drivers paradox: Synthesis and responses. Games and Economic Behavior, 20(1), 121–130.

Piccione, M., & Rubinstein, A. (1997b). On the interpretation of decision problems with imperfect recall. Games and Economic Behavior, 20(1), 3–24.

Roediger, H., Wixted, J., Desoto, K.A. (2012). The curious complexity between confidence and accuracy in reports from memory. In Nadel, L. , & Sinnott-Armstrong, W. (Eds.) Memory and law. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rowan, C. (2015). Assessing memory decay rate: What factors are the best predictors of decrements in training proficiency in a threat vehicle identification task. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 59th Annual Meeting.

Rubin, D., & Wenzel, A. (1996). One hundred years of forgetting: A quantitative description of retention. Psychological Review, 103(4), 734–760.

Savage, L.J. (1972). The foundations of statistics, 2nd edn. New York: Dover Publications Inc.

Shaw, J.S., & McClure, K.A. (1996). Repeated postevent questioning can lead to elevated levels of eyewitness confidence. Law and Human Behavior, 20, 629–653.

Trautmann, S., Vieider, F., Wakker, P. (2008). Causes of ambiguity aversion: Known versus unknown preferences. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 36, 225–243.

Voorhoeve, A., Binmore, K., Stewart, L. (2012). How much ambiguity aversion? Finding indifferences between Ellsberg’s risky and ambiguous bets. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 45(3), 215–238.

Wilson, A. (2003). Bounded memory and biases in information processing. Econometrica, 82(6), 2257–2294.

Wixted, J.T., & Wells, G. (2017). The relationship between eyewitness confidence and identification accuracy: A new synthesis. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 18, 10–65.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The authors are grateful to Michele Peruzzi for excellent z-Tree programming and Iris Fuli for maintaining the code and assisting during the experimental sessions. We thank Michael McBride, Gary Charness, W. Kip Viscusi, Marc Machina, Larry Epstein, Massimo Marinacci, John Duffy, Stergios Skaperdas and an anonymous referee for their comments and discussions.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kopylov, I., Miller, J. Subjective beliefs and confidence when facts are forgotten. J Risk Uncertain 57, 281–299 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-018-9295-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-018-9295-1