Abstract

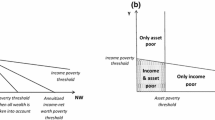

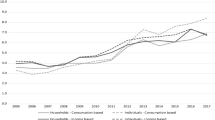

The purpose of this paper is to suggest an improved measure of financial poverty, based on household consumption and wealth as well as income. Data come from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics Australia (HILDA) Survey, which appears to be the first national socio-economic panel survey to provide longitudinal data on all three measures of household economic well-being. National measures of poverty in Australia and other Western countries are usually based only on low income. But this is conceptually incorrect; the measures lack validity. To be poor is to have a low material standard of living—involuntarily. So measures of poverty should also take account of household consumption and wealth. If a household has an adequate current level of consumption, it should not be classified as poor right now, even if its current income is low. Similarly, if it has substantial wealth (net worth), it should not be viewed as poor because it could draw down on wealth to boost current consumption. The invalidity of income-based measures has long been recognised in principle (Ringen 1987, The possibility of politics. Oxford: Clarendon Press). In practical terms, the problem is to combine measures of wealth and income, and especially consumption, in the same survey. In the 2005 HILDA Survey a battery of household expenditure items was included which, benchmarked against the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ Household Expenditure Survey for 2003–04, appeared to provide valid measurement of 53.4% of total household expenditure. These well measured items correlated 0.76 with total expenditure and, in combination with standard demographic variables, accounted for 78.3% of the variance in the total. This paper uses 2005–06 HILDA data to construct revised measures of financial poverty. The value of these measures for public policy and research purposes is illustrated. In particular, the new measures give much lower estimates of poverty than income-based measures. They can also be used to predict which households are at risk of future poverty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) now combines its main income survey—the Survey of Income and Housing (SIH)—with the Household Expenditure Survey (HES) in order to combine cross-sectional measures of income, consumption and wealth in the same survey.

However, even these households may be able to sustain their consumption level by borrowing, if they have high levels of human capital and are young or middle aged. In these circumstances it may be rational for them to borrow and rational for lenders to lend.

From a purely arithmetic point of view, it would of course be possible to measure two of these variables and calculate the third. In practice, the amount of measurement error in all surveys is such that it makes much more sense to attempt to measure all three.

The authors showed that in Canada one can account for about 79% of the cross-sectional variance total household non-durable expenditures with a regression equation which includes standard demographics plus questions eliciting spending on 4 items: food eaten at home, food eaten out, telephone costs, and gas, electricity and water.

Given a national representative sample and a representative time slice.

It is far from certain, however, that a longitudinal series of estimates of total expenditure could be validly obtained in this way. In other words, a few items may or may not provide an adequate basis for estimating annual changes in expenditure. Clearly, the prime purpose of HILDA is to provide longitudinal estimates.

The ABS Household Expenditure Surveys ask for some items to be recorded in a ‘shopping diary’ and uses a survey recall method for other more ‘lumpy’ items.

Only the 2005 HILDA data are used for benchmarking. The 2006 data are preliminary and have not yet been subject to detailed validity assessment.

We allowed ourselves a bit of leeway over 10% where there was good reason to believe that the HILDA estimates might be reasonably satisfactory. In particular, in view of large housing price increases in recent years, we accepted that HILDA’s high estimate of housing consumption might well be valid.

Total household goods and services expenditure recorded in HES 2003–04 was $893 per week. This figure includes payments of mortgage interest but not principal. In HILDA the question about mortgage payments made no distinction between interest and principal. So, for comparison with HILDA, one must add to $893 a sum of $36 which was the mean weekly amount of principal repayments in 2003–04. HILDA appears validly to measure items which in HES amount to 53.4% of $929 ($893 + $36).

Given good economic growth, one would expect a real increase of about this amount between the mid-point of the HES in January 2004 and September–October 2005 when the HILDA Survey was conducted.

This correlation was supplied by ABS, based on the HES for 2003–04.

See Browning et al. (2003, p. 557) for a similar result in Canada.

This seems realistic, given the list of items accurately measured. Clearly it would not be realistic if more consumer durables, in addition to housing, were included.

6% of current sale value is a fairly standard rule of thumb for the rent which a dwelling would be likely to attract. Clearly, actual rental values in specific suburbs can differ quite widely from this guideline.

The imputation was done by the author, using the SPSS MVA (missing values analysis) program. The imputation is likely to be revised in future years, when it is expected that the HILDA statistical team will undertake a longitudinal imputation of the kind already done for individual and household incomes and wealth.

Both HILDA results and SIH results reported here are weighted.

However, some smaller components of income, notably business income and investment income, are seriously mismeasured. Also, figures for Centrelink income support payments in HILDA are about 10% too low.

For reasons explained in Headey et al. (2005), we use an ABS benchmark for financial assets and an RBA benchmark for non-financial assets and specifically housing.

However, this apparently miraculous result is partly due to cancelling errors; both the assets and debt figures in HILDA are too low judged against benchmarks. But when debts are subtracted from assets, the errors largely cancel out.

The OECD equivalence scale was used. It is based on giving a weight of 1.0 to the first adult in the household, 0.5 to other adults, and 0.3 to children under 15. There is ample international evidence to show that point estimates of poverty are little affected by which of several reasonable equivalence scales one uses, although the specific households deemed to be poor are considerably affected by the weight given to children (Buhmann et al. 1988; Coulter et al. 1992). For a recent article proposing sophisticated improvements to equivalence scales, see Creedy and van der Ven (2005).

A more critical view is that poverty lines are essentially arbitrary. While this is arguably the case, it is also true that public opinion, as reflected in surveys in many Western countries, deems that to have an income below about 50–60% of current median household income is to be poor (Citro and Michael 1995).

Caner and Wolff (2004) propose what are in some ways more sophisticated measures of asset poverty, based on the number of months a household could survive on its assets if its income was cut off. But their measures classify almost all young households as asset poor, which in some respects is sensible but ignores the fact that many have good access to loans.

Strictly speaking, the dates of the wealth, consumption and income poverty measures are not the same. The wealth and consumption measures apply to the dates on which the Survey was conducted (September–October 2005 and September–October 2006). The income measures relate to Financial Years 2004–05 and 2005–06.

It also quite important to realise that household consumption is more highly related to net worth (correlation in 2006 = 0.65) than to household net income (correlation = 0.40).

In principle, gifts should be recorded as income in HILDA, but survey research experience suggests substantial under-recording.

As noted earlier, parental subsidies should be recorded in surveys as inter-household transfers but are, in practice, often omitted as a source of income.

It is not really clear why. In some cases they may be saving a lot; for example, to buy a house.

Results are very similar if the measure used is income + consumption poverty, based on 60% of median lines.

Results for the prime working age group (25–54) followed the same pattern as for the total population, although overall poverty rates were considerably lower.

Of course, if people in this group had had a great deal of wealth in 2005, only extreme spending could have reduced them to income + consumption + wealth poverty in 2006. In fact, only 1.9% were reduced to income + consumption poverty, indicating that wealth really does provide an effective buffer in most cases.

About two-thirds of these individuals were already below the income poverty line in 2005 and then fell below the income + consumption + wealth poverty line in 2006 because their consumption fell (or, in a few cases, because of a decline in net worth). The remaining one-third were above the income poverty line in 2005 and appear to have become poor in 2006 partly because of ‘overspending’ in the previous year.

One case: loans were made available to low income people to tide over emergencies (e.g. to cover extra expenses at the beginning of the school year) in 1993–96 when Peter Baldwin was Minister of Social Security. The Victorian Government appears to have operated a somewhat similar scheme in the 1980s.

Again, multivariate analysis confirmed these results.

The HES total for the items was $929, being $893 for what HES terms ‘total goods and services expenditure’, plus $36 for mortgage principal repayments. HES separates out mortgage interest and mortgage principal and does not include the latter in total goods and services expenditure. By contrast, the HILDA mortgage repayment question made no distinction between interest and principal payments.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2000). Household expenditure survey 1998–99 (Cmnd 6535.0). Canberra: ABS.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2005). Household expenditure survey 2003–04 (Cmnd 6535.0). Canberra: ABS.

Barrett, G. F., Crossley, T. F., & Worswick, C. (2000). Consumption and income inequality in Australia. Economic Record, 233, 116–138.

Browning, M., Crossley, T. F., & Weber, G. (2003). Asking consumption questions in general purpose surveys. Economic Journal, 113, 540–567.

Buhmann, B., Rainwater, L., Schmaus, G., & Smeeding, T. M. (1988). Equivalence scales, well-being, inequality and poverty: sensitivity estimates across ten countries using the Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) database. Review of Income and Wealth, 34, 115–142.

Caner, A., & Wolff, E. N. (2004). Asset poverty in the United States, 1984–99: Evidence from the panel study of income dynamics. Review of Income and Wealth, 50, 493–518.

Citro, C. F., & Michael, R. T. (1995). Measuring poverty: A new approach. Washington, DC: National Academic Press.

Coulter, F. A. E., Cowell, F. A., Jenkins, S. P. (1992). Equivalence scale relativities and the extent of inequality and poverty. Economic Journal, 102, 1067–1082.

Council of Australian Governments (COAG) (2006). Human capital reform: Report by the COAG national reform initiative working group (February).

Creedy, J., & Tan, L. (2007). The relationship between personal income and net worth. Australian Economic Review, 40, 165–181.

Creedy, J., & van der Ven, J. (2005). Taxation, reranking and equivalence scales. Bulletin of Economic Research, 57, 13–36.

Dvornak, N., & Kohler, M. (2007). Housing wealth, stock market wealth and consumption: a panel analysis for Australia. Economic Record, 261, 117–130.

European Commission, EUROSTAT (2000). European social statistics, income, poverty and social exclusion. Luxembourg: European Union.

Friedman, M. (1957). A theory of the consumption function. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Goodin, R. E., Headey, B., Muffels, R., & Dirven, H.-J. (1999). The real worlds of welfare capitalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Headey, B., Warren, D., & Harding, G. (2006). Families, incomes and jobs: A statistical report of the HILDA survey. Melbourne: Melbourne Institute.

Headey, B., Warren, D., & Wooden, M. (2007). The structure and distribution of household wealth in Australia: Cohort differences and retirement issues. Canberra: Department of Family and Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FACSIA).

Headey, B., Marks, G., & Wooden, M. (2005). The structure and distribution of household wealth in Australia. Australian Economic Review, 38, 159–175.

Nolan, B., Maitre, B., O’Neill, D., & Sweetman, O. (2000). The distribution of income in Ireland. Dublin: Oak Tree Press.

Ringen, S. (1987). The possibility of politics. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Ringen, S. (1988) Direct and indirect measures of poverty. Journal of Social Policy, 17, 351–365.

Saunders, P. (1998). Development of indicative budget standards for Australia, Policy Research Paper No. 74, University of NSW, Social Policy Research Centre.

Saunders, P., & Adelman, L. (2004). Resources, deprivation and exclusion approaches to measuring well-being: a comparative study of Australia and Britain. 28th General conference of the international association for research in income and wealth, cork, Ireland (Aug. 22–28).

Saunders, P. (2005). Poverty wars: Reconnecting research with reality. Sydney: University of NSW Press.

Sen, A. (1999). Development and freedom. New York: Anchor Books.

Townsend, P. (1979). Poverty in the United Kingdom. Harmondsworth, Penguin.

Watson, N., & Wooden, M. (2004). Assessing the quality of the HILDA survey Wave 2 Data. HILDA Technical Paper (May).

Yates, J. (1991). Imputed rent and income distribution. The Review of Income and Wealth, 40, 43–66.

Acknowledgement

Many thanks to Melbourne Institute colleagues John Freebairn and Roger Wilkins for valued comments and suggested revisions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Benchmarking—Household Expenditure Items Measured Validly In HILDA 2005 Compared With HES 2003–04

Appendix: Benchmarking—Household Expenditure Items Measured Validly In HILDA 2005 Compared With HES 2003–04

This appendix benchmarks HILDA results for 2005 against the Household Expenditure Survey (HES) for 2003–04. Weekly expenditures are shown. The HILDA figures have been deflated by 4.7% to allow for the increase in CPI between January 2004 (mid-point of the HES data collection) and September 2005 (mid-point of the HILDA data collection). Only items which appear to be reasonably accurately measured in HILDA are shown. A margin of plus or minus 10% between HILDA and HES was considered reasonably satisfactory, subject to a few small additional deviations explained below. In general, one would expect the HILDA figures to be a few percent higher than the HES figures, because real disposable per capita (and hence per household) incomes increased in the 21 months between the two data collections. In fact, this is what we do find.

Using a band of plus or minus 10%, the well measured items amount to 53.4% of total household expenditure on goods and services as reported in HES.Footnote 35 Within HES these items correlated 0.76 with total expenditure. Also within HES, a regression equation using these items plus standard demographics accounted for 78.3% of the variance in total expenditure.

Household Weekly Expenditures

HES | HILDA | |

|---|---|---|

2003–04 | 2005* | |

Groceries (note i) | $131 | $142 |

Alcohol | $23 | $22 |

Tobacco | $12 | $13 |

Public transport & taxis | $7 | $7 |

Meals eaten out | $42 | $41 |

Motor fuel | $33 | $34 |

Car maintenance | $14 | $15 |

Telephone | $27 | $26 |

Home fuel | $23 | $22 |

Home maintenance | $21 | $19 |

Health insurance | $17 | $15 |

Education | $18 | $16 |

Mortgage payments (note ii) | $82 | $92 |

Rent (note iii) | $46 | $51 |

Total | $496 | $515 |

-

(i)

The HILDA question, which was made more precise in 2006, is related specifically to food, cleaning products, pet food and personal care products.

-

(ii)

The difference between HES and HILDA is a little over 10%. Given the big increase in house prices in recent years this difference seems acceptable. Note that households are included even if they pay no mortgage.

-

(iii)

The difference between HES and HILDA is a little over 10%. Given the increase in rents in recent years this difference seems acceptable. Note that households are included even if they pay no rent.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Headey, B. Poverty Is Low Consumption and Low Wealth, Not Just Low Income. Soc Indic Res 89, 23–39 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9231-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9231-2