Abstract

Ribozymes are huge complex biological catalysts composed of a combination of RNA and proteins. Nevertheless, there is a reduced number of small ribozymes, the self-cleavage ribozymes, that are formed just by RNA and, apparently, they existed in cells of primitive biological systems. Unveiling the details of these “fossils” enzymes can contribute not only to the understanding of the origins of life but also to the development of new simplified artificial enzymes. A computational study of the reactivity of the pistol ribozyme carried out by means of classical MD simulations and QM/MM hybrid calculations is herein presented to clarify its catalytic mechanism. Analysis of the geometries along independent MD simulations with different protonation states of the active site basic species reveals that only the canonical system, with no additional protonation changes, renders reactive conformations. A change in the coordination sphere of the Mg2+ ion has been observed during the simulations, which allows proposing a mechanism to explain the unique mode of action of the pistol ribozyme by comparison with other ribozymes. The present results are at the center of the debate originated from recent experimental and theoretical studies on pistol ribozyme.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

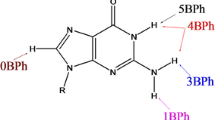

Enzymes are traditionally considered as made of proteins. Nevertheless, there is a small number of enzymes, called ribozymes, that are made from RNA. Most of the ribozymes are huge complex biological machines formed by a combination of RNA and proteins but there is a reduced number of much smaller ribozymes that are formed just by RNA. These are called the self-cleavage ribozymes because they catalyze the site-specific breaking of RNA by the nucleophilic attack of O2’ to the phosphorous atom thus provoking the breaking of the bond with the O5’ atom (see Scheme 1).

Five different self-cleavage ribozymes have been discovered since 1986: hammerhead [1], hairpin [2], hepatitis delta virus (HDV) [3], Varkud satellite [4], and glmS [5]. More recently, four more self-cleavage ribozymes were reported in a short period of time: twister [6], twister sister [7], pistol [7], and hatchet [7]. It is believed that many self-cleaving ribozymes are still working in living organisms after several billions of years [8].

The catalytic activity of self-cleaving ribozymes has been explained based on four possible different factors [9]: (α) the appropriate in-line orientation of the 2’-oxygen nucleophile, phosphorus electrophile, and the 5’-oxygen leaving group in the active site; (β) the electrostatic neutralization of the negative charge of non-bridging phosphate oxygen atoms; (γ) the deprotonation of the 2’-hydroxyl group by a base, i.e. the activation of the nucleophile; and (δ) the neutralization and stabilization of the 5’-oxygen leaving group by an acid (see Scheme 1). Recently, the deprotonation of the 2’-hydroxyl group has been attributed to two different variations [10,11,12]: by forming a hydrogen bond interaction between species of the active site and the 2’-oxygen atom, thus increasing its acidity (γ’), or by forming hydrogen bond interactions between the non-bridging oxygen atoms of the phosphate group with other groups different from the 2’-oxygen nucleophile thus favoring the transfer of the H2’ to another base of the active site (γ’’). More recently, primary, secondary and tertiary contributions have been defined for β, γ and δ factors [13].

A question of debate intrinsically connected to the different hypothesis proposed to explain the origin of catalysis of RNA-enzymes is the role assigned to the magnesium cations that have been identified in the cleavage site in some enzymes [8]. Some authors propose that the folded structure of the RNA itself contributes more to the catalytic function and that the divalent cations would play a structural role [14]. In contrast, other authors suggest that the catalysis in self-cleaving ribozymes is basically due to the role of the Mg2+ cations [15, 16]. It seems that hairpin, VS, and twister use a guanine as a base and an adenine as an acid, although in the later the proton donor role is played by the N3 atom and not by the N1 atom [17, 18]. In the env22 twister ribozyme, X-ray diffraction structures show that both an invariant guanosine and a Mg2+ are directly coordinated to the non-bridging phosphate oxygens at the self-cleavage site [19]. Further theoretical studies on the twister ribozyme suggest that the general acid must be the Mg2+-bound water molecule [20]. Other theoretical studies have been also focused on the role of the cation in hammerhead [21] and glmS ribozymes [22].

Structures of pistol ribozymes have been recently disclosed from X-ray diffraction techniques [23, 24], biochemical analysis [25], and atomic mutagenesis studies [26]. As discussed in some reviews [27,28,29], the structures show how the G-U cleavage site adopts a splayed-apart conformation with in-line alignment of the O2’ nucleophile with the P-O5’ cleaving bond. The N1 atom of guanine G40 is properly positioned to act as a general base while the N3 and 2’-OH positions of adenine A32 are located to be a candidate for general acid catalyst. This, together with the activity detected in the A32G pistol ribozyme mutant suggested that purine-32 N3 is of crucial importance for the pistol ribozyme activity [26]. In addition, an increase of one pKa unit of A32 was measured [23], and a second structure of the pistol ribozyme was solved with a guanine instead of an adenine in position 32 [24]. Atom-specific mutagenesis showed that neither the N1 nor the N3 base positions of A32 must be involved in the catalytic process [26].

As mentioned above, a critical question of debate about the activity of the small ribozymes is the role of Mg2+ cations. The direct participation of the divalent metal ion are ambiguous [25]. An strategy of testing the role of the Mg2+ was based on the replacement of the nonbridging oxygens of the scissile phosphate by sulfur atoms, since the S-Mg2+ interaction is much weaker than the O-Mg2+. This sulfur-containing pistol ribozyme showed a hinder activity [25], which was interpreted to conclude that the pistol ribozyme does not require inner-sphere coordination of divalent cation for catalysis [28].

Interestingly, it has been stressed the similarity between the pistol ribozyme crystal structure [23] with recent crystal structures of hammerhead ribozyme at pH 8 [16] and the structure of a hammerhead ribozyme transition state vanadate mimic [30]. Recently a new structure of the pistol ribozyme has been obtained and it has been compared to the structure of the hammerhead ribozyme. They present a high structural similitude but, while there is an agreement concerning the base, there is not regarding the acid that protonates the leaving group [31]. Finally, crystal structures of vanadate mimicking the transition state, and the products have been published [32].

Unfortunately, the crystal structure in the pistol, where the 2’-O nucleophile was substituted by a deoxy 2’-H, traps the ribozyme in a pre-catalytic state. Moreover, one has to consider the effect of the crystalline environment, as RNA structures can be influenced by crystal packing artifacts that are sensitive to crystallization conditions. Thus, X-ray crystal structures represent static pictures of a deactivated enzyme that is not the same as in a solution [33]. So, some discrepancies between biochemical studies and crystallographic data appear. Classical molecular dynamic (MD) simulations have been carried out to clarify this point [34,35,36].

The present paper represents, to our knowledge, the first theoretical study of the reactivity of the pistol ribozyme utilizing classical and QM/MM hybrid MD simulations. The reaction mechanism of the self-cleavage RNA reaction, with special attention to the role of the active site Mg2+ cations, will be explored.

2 Computational Methods

2.1 Model Set Up

The X-ray structure of the pistol ribozyme (PDB ID 5KTJ) [24] was used to build the model for our simulations. The self-cleaving pistol ribozyme can be found as a dimer in the PDB file, containing two pairs of chains, chains A and B, which were both selected along with the corresponding counterions. The dimer structure contained three types of counterions, five samarium (III) ions, six cobalt hexammine (III) complexes, and nine magnesium ions. All samarium (III) ions were substituted by magnesium ions and the cobalt hexammine (III) complexes were substituted by magnesium hexahydrate complexes, containing finally a total of twenty magnesium ions in the final model. Then, because the cleavage site of the pistol ribozyme is between G10 and U11, the crystal structure contains a non-cleavable modified dG base. In order to obtain a reactive form for this cleavage site, O2’ was modeled in place so the deoxyribose found in the X-ray structure was transformed into a ribose nucleotide. Afterwards, the tLEAP module of the AmberTools [37] package was used to add all missing hydrogen atoms at pH = 7.0. Three different models were initially established as a starting point for exploring the role of the residues close to the cleavage site, all of them solvated in a box of 72 × 73 × 79 Å3 TIP3P [38] water molecules. In the first model, M1, the standard protonation state for all the nucleobases was set and 23 sodium counterions were added. The total system contains 37,672 atoms. The second model, M2, was set with the standard protonation state for all the nucleobases but guanine G40, which was parametrized as deprotonated in the N1 atom, 24 sodium counterions were added, with a total of 37,552 atoms. The third model, M3, was set as the M2 model, with guanine G40 deprotonated in the N1 nitrogen, and additionally, guanine G32 protonated in the N3 nitrogen atom. 23 sodium counterions were added, with a total of 37,681 atoms. Parameters for Mg2+, were adapted from Villa and co-workers [39]. Parameters for guanine nucleobase deprotonated in N1, and guanine nucleobase protonated in N3 were obtained using the Antechamber software [40] as provided in Electronic Supplementary Material.

NAMD [41] software was used to perform the molecular dynamics (MD) simulation, with AMBER force field ff99 [42] with the parmbsc0 [43] and parmχOL3 [44] dihedral modifications, supplemented by van der Waals parameters for phosphates [45] for modelling the ribozyme and TIP3P forcefield for the solvent and counterions. The simulation protocol was the same for all three systems. First, the models were minimised using conjugate gradient energy minimization of 100,000 steps, and later gradually heated up to 297 K with 0.001 K increments. Then 100 ps of NPT equilibration was performed using the Nosé-Hoober Langevin piston [46] as implemented in NAMD for pressure control. Finally, 50 ns of NVT production were performed. In all simulations periodic boundary conditions were used, the Langevin thermostat [47] was set as temperature control and the time step was 1 fs.

2.2 QM/MM Calculations

A fourth model was prepared for the QM/MM exploration. The protonation states of the different species in this new model are equivalent to those of the M1 model but, additionally, a water molecule originally coordinated to the Mg2+ was substituted by a hydroxide ion OH−, and a sodium counterion was added.

After equilibrating the system as described above for the other models, a structure was chosen based on MD analysis, selecting an adequate reactive conformer for exploring the reaction path. In particular, the selected representative conformation from the equilibrated dynamics presents internal coordinates corresponding to a reactive conformation, taken into account the self-cleavage RNA reaction mechanism to be studied (see a discussion about the reactive conformation in next section). The system was simulated using a QM/MM potential, where the QM subsystem was composed of the ribose of guanine G10, the phosphate group of uracil U11, and the coordination sphere of the Mg2+ ion, containing a total of 54 atoms and 9 hydrogen link atoms where covalent bonds were cut in the QM-MM partition (Fig. 1). The QM subset of atoms was treated with the AM1d (Mg from AM1/d [48] and H, O, and P from AM1/d-PhoT [49]). The rest of the system was treated with the AMBER and TIP3P force fields for the ribozyme, counterions, and the solvent, as implemented in the fDYNAMO library [50,51,52]. Potential energy surfaces, PESs, for each chemical step, were obtained by grid scanning of selected distinguished reaction coordinates. Then, the stationary points were optimized by a micro–macro iteration method [53] at AM1d/MM level of theory. These structures were characterized by the matrix of second energy derivatives, and the minimum energy path (MEP) was finally computed as the intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) path.

Finally, the Nudge Elastic Band method (NEB) as implemented in QM3 [54] was used in order to obtain an additional description of MEP at a high level of theory, by using the M06-2X DFT functional [55] and the 6–31 + G(d,p) basis set for treating the QM subset of atoms and the AMBER and TIP3P force fields respectively for treating the MM subset of atoms. From the starting structure, the proposed reaction products were constructed and localized. Then the NEB method was used, where a geometrical interpolation of the structures is performed followed by an optimization of the full path. Once the final MEP structures were obtained, the structure corresponding to the highest energy point was optimized by a micro–macro iteration method at M06-2X/MM level of theory and the MEP was recalculated by computing the IRC paths at the same level of theory.

3 Results and Discussion

The present study has been divided into two stages. First, a deep insight into the time evolution of the structures of pistol ribozyme in aqueous solution has been carried out starting from the crystal X-ray structure by classical MD simulations. Different models were set up, as described in the previous section. A dynamic description of the systems will be then obtained. Second, after selecting the protonation state of the different species of the active site in a proper reactive conformation, the self-cleavage RNA reaction will be explored by obtaining the potential energy profile from hybrid QM/MM simulations.

3.1 Molecular Dynamics Simulations

As explained in the previous section, three models were prepared to explore the possible starting point for the self-cleavage reaction: M1, where the protonation of the base was according to the canonical system with no additional protonation changes; M2, where the guanine G40 is deprotonated in N1 position; and M3, where the guanine G40 is deprotonated in N1 and guanine G32 protonated at the N3 position. The analysis of the geometries along the three unconstrained independent MD simulations will be used to test whether G40 and G32 appear in a proper position to act as acid and base, as proposed in the literature from analysis of X-ray structures (see Introduction section).

The time evolution of key geometrical variables along the 50 ns MD simulations starting from model M1 is shown in Fig. 2. The first interesting observation is the change of the inner sphere of the Mg2+ cation, initially interacting with N7 of G33 but after ca. 5 ns Mg2+ interacts with the proRP oxygen atom of the phosphate group (see Fig. 2a). The evolution of the distance between NH2-G40 that stabilizes the negative charge of this oxygen atom dramatically changes at this point, as observed in Fig. 2b. A similar change in the coordination of the Mg2+ from the crystal structure to the aqueous solution was detected by Gaines and York in MD simulations of twister ribozyme [56]. Apparently, this change is correlated with the evolution of other key geometrical variables presented in Fig. 2. Thus, the value of the O2’–P–O5’ angle noticeable increases at 5 ns, coincidently with the change in the coordination of the cation, and it then starts to oscillate up to values close to the linearity (see Fig. 2c). The evolution observed in the O2’–P–O5’ angle is also correlated with the O2’–P distance, depicted in Fig. 2d. This correlation can be analyzed with Fig. 2g; despite not-negligible oscillations are observed, the shortest distances between the O2’ and P atoms (ca. 3 Å) are achieved when the O2’–P–O5’ angle oscillates around 160 degrees. The definition of the limits of an “active” inline attack geometry was established by York and co-workers, as the one that has an O2′–P′O5′ angle of more than 125° and O2′–P distance of less than 3.5 Å [57]. This behavior is confirmed in previous studies of related models, where reactive conformations appear less often during MD simulations with the calculated probabilities not higher than 7.7% [57,58,59].

Time evolution of key geometrical variables along the 50 ns MD simulations starting from model M1: a Mg2+–O proRP distance; b HNH2G40–O proRP; c O2’–P–O5’ angle; d O2’–P distance; e N1G40–O2’ distance; f HO2’–O proSP distance. Panel “g” shows a correlation between the O2’–P–O5’ angle and the O2’–P distance on the population of structures obtain during the MD simulations. Axis in panel “g” represent the limits of the active conformations, as explained in the text. Red dots correspond to the snapshot selected as reactive conformation. All distances in Å and the angle in degrees

Figure 2e shows how N1G40–O2’ distance is perfectly equilibrated after 30 ns of the MD simulation. It is interesting to notice that this equilibrated configuration represents a geometry in which the hydrogen atom of the N1 position of G40 is pointing towards the O2’ thus acting as a hydrogen bond donor, decreasing the pKa of the O2’. This role of G40 contrasts with the one that has been traditionally assigned. Thus, the fact that G40 (N1 position) is a highly conserved residue in the crystal structures of pistol ribozyme has been associated with a role as a general base responsible for the abstraction of the proton from O2’ [23, 24]. Interestingly, our results and interpretation would be in agreement with the proposed catalytic strategy of small nucleolytic ribozymes coined as γ’ by Bevilacqua and co-workers [12]. In a more recent nomenclature, this would be a referred to secondary (2°) γ catalysis [13, 35, 60]. The equilibrated conformation obtained from our MD simulations is also characterized by a strong hydrogen bond interaction between the hydrogen atom of O2’ and the proSP oxygen atom of the scissile phosphate, as observed in Fig. 2f. A snapshot from the last 10 ns of the MD simulation (see red dots in Fig. 2) that represents the commented features of a reactive conformation is presented in Fig. 3.

Representative snapshot of the equilibrated geometry of a reactive conformation (red dots in Fig. 2). Distances in Å, angle in degrees

The corresponding analysis of the MD simulations with the other two models, M2 and M3, clearly shows that different protonation states of guanine G40 and guanine G32 render non-reactive conformations of the active site. In particular, the time evolution of the O2’–P–O5’ angle and the O2’–P distance in the M2 model does not show any improvement along the simulation (see Fig. 4). As shown in Fig. 4a, the coordination of the Mg2+ has already changed in the initial structure of the trajectory and it is already interacting with the proRP oxygen atom. This is confirmed by the long HNH2G40–O proRP distance (see Fig. 4b). While the initial structure shows both large angle and short distance (ca. 150 degrees and 3.3 Å, respectively) after 10 ns of the MD simulation the O2’–P distance oscillate around values close to 4 Å and the O2’–P–O5’ angle decreases to values around 135 degrees. This combination of values is clearly characterizing non-reactive conformations for the subsequent RNA cleavage (see Fig. 4f). Moreover, the distance between the N1 atom of G40 and the O2’ atom is always around 5 Å (see Fig. 4d), probably due to the electrostatic repulsion between the proSP and the proRP non-bridging oxygen atoms and the negatively charged G40. Thus, G40 cannot act as a base to abstract the proton from O2’. Finally, the O2’ atom is not activated in this M2 model, as it was in model M1, due to the lack of interaction with G40. As a consequence, the interaction between the H atom of O2’ and the proSP non-bridging oxygen atom is not observed during the 50 ns of the MD simulation (see Fig. 4e).

Time evolution of key geometrical variables along the 50 ns MD simulations starting from model M2: a Mg2+–O proRP distance; b HNH2G40–O proRP; c O2’–P–O5’ angle; d O2’–P distance; e N1G40–O2’ distance; f HO2’–O proSP distance. Panel g shows a correlation between the O2’–P–O5’ angle and the O2’–P distance on the population of structures obtain during the MD simulation. Axis in panel “g” represent the limits of the active conformations, as explained in the text. Red dots correspond to the snapshot selected as reactive conformation. All distances in Å and the angle in degrees

The simulation with model M3 reveals that the hypothesis of having deprotonated guanine G40 and the protonated N3 of guanine G32 does not appear realistic. As observed in the time evolution of the key distances (see Fig. S1 of the Electronic Supplementary Material), G32 is dramatically displaced from the O5’ atom, thus precluding its possible role of improving the leaving group character of O5’ atom. This result is in agreement with mutational studies, as mentioned in the Introduction section.

3.2 AM1d/MM Results

Once explored the possible conformations of the reactants-like structures of the active site of the pistol ribozyme, the self-cleavage of RNA was first studied based on an exploration of potential energy surfaces (PESs). At this point, since the previous MD simulations suggest that G40 cannot be deprotonated, the first question is elucidating which is the species in the active site that can act as a base to deprotonate the O2’ nucleophilic group. An attempt to transfer the H atom from O2’ to the proSP non-bridging oxygen atom rendered a barrier too high for being compatible with this biological catalytic process, as confirmed with the higher level DFT/MM calculations (see below). The presence of the positively charged Mg2+ interacting with the non-bridging oxygen atom must be impeding this proton transfer.

An exploration of the active site does not render any evident candidate to act as a base. Then, once discarded the G40 and the proSP oxygen atom as acceptors of this proton transfer, we supposed that a deprotonated water molecule coordinated to the Mg2+ acts as a base, as originally proposed for a reduced model of the hammerhead ribozyme by Torres, Lovell and co-workers [61], and later by Leclerc and Karplus [62]. This is also in agreement with the proposal of Bevilacqua and co-workers in the HDV ribozyme [63] and more recently, Lilley and co-workers in the twister sister [64].

The AM1d/MM PES generated with the O2’-P distance and the anti-symmetric combination of distances defining the proton transfer from O2’ to the hydroxyl group coordinated to the Mg2+ as distinguished reaction coordinates is presented in Fig. 5, while the resulting energy profile is shown in Fig. 6. According to the potential energy surface, the proton transfer precedes the nucleophilic attack. This step was confirmed by localizing a TS, TS-1, and running an IRC down to the valleys of reactants (R) and an intermediate (I) (see black stars in Fig. 5). This result suggests a pre-equilibrium before the nucleophilic attack. The activation of the O2’ by the hydrogen bond interaction with the N1 atom of G40 has decreased its pKa, thus facilitating its deprotonation, but it also decreases its capability to form a new covalent bond with the P atom. The activation of the nucleophilic O2’ and the nucleophilic attack take place in a sequential way and not in a concerted manner. This proposal is in agreement with previous theoretical simulations on Hammerhead [65], and HDV [66].

AM1d/MM PES obtained with the antisymmetric combination of interatomic distances defining the proton transfer from O2’ to a hydroxyl group coordinated to the Mg2+ cation and the O2’ nucleophilic attack to the phosphorous atom. Distances in Å. Black dots represent the position of fully optimized structures (minima and saddle point of order one) while black stars identify the structures generated along the IRC traced from the optimized TS-1

An optimized structure of the TS-1, displayed in Fig. 7a, shows how the proton is in between its donor and acceptor atoms (1.27 and 1.40 Å to the O2’ and the oxygen atom of the hydroxyl group, respectively) while the large distance between O2’ and the phosphor atom (3.11 Å), together with a short distance of the scissile bond between the phosphor atom and the leaving group (P-O5’ distance equal to 1.65 Å), reveal that the nucleophilic attack is not taking place concertedly with the proton transfer. Analysis of the coordination sphere of the Mg2+ from reactants to the intermediate (see Table 1) provides interesting conclusions. First, it is evident that the coordination sphere is qualitatively invariable from reactants to the Int1. Nevertheless, it seems that the Mg2+ is displacing towards the two oxygen atoms of the phosphoryl groups of G33 and U35, and the oxygen atom of G32 that will act as an acid in the protonation of the O5’ leaving group. There is a water molecule that is coupled to the Mg2+ as well as the proRP non-bridging oxygen atom. The OH− is also following this displacement but, because it is being transformed from a hydroxyl to a water molecule, the interatomic distance is slightly increasing. A migration of the Mg2+ was also observed in theoretical simulations of the Hammerhead ribozyme [65, 67, 68], although our calculations do not describe such dramatic variation. Interestingly, as observed in Fig. 7a, a water molecule that is coordinated to the second Mg2+ cation is interacting with the O6 of G40 which increases its acidity, thus increasing the strength of the hydrogen bond interaction with O2’. Also, another water molecule coordinated to the same Mg2+ cation was found to interact with the proSP oxygen atom, stabilizing the negative charge on this atom.

The structures obtained as intermediates clearly show a long distance between the N3 atom of G32 and the O5’ atom of the scissile phosphoryl bond. These results, in agreement with experimental data [26], discard the hypothesis of the N3 atom of G32 role as the acid to protonate the O5’ leaving group. In contrast, an inspection of the geometry of the intermediate obtained after activation of the nucleophile (Int) suggests that the hydroxyl group of the sugar ring of G32 does this role. This hydroxyl group, as commented above, is in the coordination sphere of the Mg2+, which increases its acid character. Thus, the distinguished reaction coordinates employed to generate a PES corresponding to the nucleophilic attack and leaving group departure were the anti-symmetric combination of distances that define the breaking and forming bonds, (O5’-P) – (P-O2’), and the anti-symmetric combination of distances that define the proton transfer from O2’ of G32 to the O5’, (O2’G32-H) – (H-O5’), as seen in Fig. 8. The resulting potential energy profile is shown in Fig. 6.

AM1d/MM PES obtained with the anti-symmetric combination of distances defining the breaking and forming bonds and the anti-symmetric combination of distances defining the proton transfer from O2’ of G32 to the O5’. Black and red dots represent the position of fully optimized transition structures TS-2a and TS-2b, respectively, while the stars identify the structures generated along the IRCs traced from the optimized transition states. Distances in Å and iso-energetic lines in kcal·mol−1

The PES presented in Fig. 8 shows how the RNA breaking can take place through two different concerted mechanisms and, as observed in Fig. 6, both paths have quite similar energy barriers. The reaction path through the TS-2a (black dot in Fig. 8) describes a process where the proton transfer would take place after the nucleophilic attack, while in the reaction path through the TS-2b (red dot in Fig. 8), the protonation of the leaving O5’ atom would take place before the nucleophilic attack. Details of the optimized structures are displayed in Fig. 7b and c, where key distances and the O2’-P-O5’ angle are reported. As observed in the geometries, that are in agreement with their position on the PES of Fig. 8, TS-2a must be considered as a late-TS from the nucleophilic attack and the scissile P-O5’ bond point of view. According to the same criterion, the TS-2b would be describing an early-TS. This observation is related to the different values of the hydrogen bond distance between the G40 and the O2’. Thus, when the O2’-P bond is in an advanced stage of the reaction (TS-2a), the negative charge in O2’ has been reduced and its interaction with the HN1 atom of G-40 is weaker (longer HN1-O2’ distance, 2.49 Å). On the contrary, when the O2’-P bond is in an early stage of the reaction (TS-2b), the charge on O2’ is larger (in absolute value) and the distance is significantly shorter (HN1-O2’ distance equal to 1.85 Å). Regarding the proton transfer from G32 to the O5’ leaving group, this is in an early stage of the process in the TS-2a while in the TS-2b the proton transfer to O5’ atom is more advanced.

The evolution of the distances that define the coordination sphere of the Mg2+ from the intermediate to products, listed in Table 1, supports the conclusions derived from the analysis of the first step. Thus, despite the coordination sphere is qualitatively invariant, the small variation of some distances confirms the tiny migration of the Mg2+ from its interaction with the pro-RP oxygen atom to the O2’ of G32 and the oxygen atom of the phosphate group of U35. As discussed above, based on our results and in agreement with previous studies in hammerhead ribozyme [65, 67, 68], this movement is associated with a negative charge migration as the reaction proceeds. Finally, as deduced from the energy profiles shown in Fig. 6, the high energy barrier values obtained at the AM1d/MM level seems to be overestimated. Then, higher level of theory, M06-2X/MM, was used to support that analysis based on geometries of stationary points can be considered as robust.

3.3 M06-2X/MM Results

Because several authors have suggested that G40 acts as a base [23, 24, 28, 31, 34], we have done an additional effort to explore this possibility based on high level M06-2X/MM calculations starting from structures where the coordination of the Mg2+ has moved from N7 of G33 to the proRP oxygen of the phosphate. Thus, this can be a reactive conformation for the proposed mechanism. Consequently, transition state structures were optimized from structures derived from NEB simulations, as described in the Methods section. Thus, the possible role of the unprotonated G40 as the base to abstract the proton from O2’ was first explored, localizing a transition state structure for this process (see Fig. S2 in the Electronic Supplementary Material). Second, a transition state defining the deprotonation of the O2’ by a hydroxyl anion coordinated to the Mg2+ was localized (see Fig. 9). And third, a possible concerted process for the O2’ nucleophilic attack to the P atom and the P-O5’ bond breaking was confirmed after localizing a transition state for the self-assisted mechanism corresponding to the proton transfer from O2’ to the proSP non-bridging oxygen, concomitant with the attack to the phosphorous atom, was fully optimized (see Fig. S3 in the Electronic Supplementary Material). Analysis of the energy profiles obtained at M06-2X/MM shows that first and third possibilities can be ruled out,according to the high energy barriers obtained after running the IRC paths to the corresponding reactant state, 26.8 and 63.1 kcal·mol−1, respectively; while the proton transfer to the hydroxyl anion coordinated to the Mg2+ renders an energy barrier of just 2.1 kcal·mol−1 (see Fig. S4 in the Electronic Supplementary Material).

The breaking of the P-O5’ bond can be assisted by G32 as an acid to transfer a proton to the O5’ atom. The located transition state (see Fig. S5 in the Electronic Supplementary Material) renders nevertheless a high energy barrier (ca. 62 kcal·mol−1). These high level optimized structures displayed in Fig. S3 and S5 are qualitatively equivalent to those optimized at lower level displayed in Fig. 7a and Fig. 7c which confirms that, despite the exploration of the mechanisms based on classical MD simulations and AM1d/MM optimizations provide overestimated energy barriers, the geometries can be used for reliable analysis.

Finally, because it has been also suggested that a water molecule coordinated to the Mg2+ can act as an acid to protonate O5’, [26, 31, 34] this process has been also explored at M06-2X/MM level but any attempt to localize a transition state was unsuccessfully, probably due to the relative orientations of the different species that prevent the direct proton transfer.

4 Conclusions

In the present work, a computational study of the reactivity of the pistol ribozyme has been carried out by means of classical MD simulations with AMBER and TIP3P forcefields for modelling the ribozyme and solvent, respectively, and QM/MM hybrid calculations with the QM sub-set of atoms described at semiempirical (AM1d) and DFT (M06-2X) level of theory. Different mechanisms for the self-cleavage RNA reaction have been explored with special attention to the role of the active site Mg2+ cations. The results have been compared to those previously obtained from other ribozymes such as hammerhead ribozyme. The study was initiated with a deep insight into the possible protonation state of the titratable species in the active site by preparing different models and an analysis of the evolution of the geometries along the corresponding unconstraint MD trajectories. This is a key step for the following exploration of the mechanism because of the uncertainty derived from the previous structural studies in this ribozyme. Analysis of the MD simulations was used to test whether G40 and G32 appear in a proper position to act as base and acid, respectively, as proposed in previous studies [27, 28, 34] from analysis of X-ray structures [23, 24, 31, 32]. Our results reveal that only the model where the protonation of the nucleotide base was according to the canonical state renders reactive conformations of the active site. Moreover, it is important to note that the analysis of the evolution of the geometries along the MD trajectory shows a change of the inner sphere of the Mg2+ cation. In particular, the interaction with N7 of G33 is lost and a new interaction is established with the proRP oxygen atom of the phosphate group. This result is in contrast with recent experimental and theoretical studies [32, 35, 36] suggesting that Mg2+ is kept in the inner-sphere of N7 of G33, which means to be in the outer-sphere of the proRP oxygen atom.

All the following attempts to explore different mechanisms based on QM/MM simulations are then initiated from this new configuration where the proRP oxygen is placed in the inner-sphere of Mg2+. Our results suggest a crucial role to the Mg2+, activating a hydroxyl coordinated to the cation to act as a base in the initial step, and activating the G32 to act as an acid in the final P-O5’ breaking bond step. Nevertheless, it must be pointed out that these conclusions open the door for possible discussions either because of the limitations of the classical MD simulations themselves or because of the possible source of error derived from the parametrization of the force fields, especially the Mg2+ cation. Nevertheless, Leonarski et al. [69] claimed that, in general, the assumed assignation of the coordination of Mg2+ to N7 of a guanine is questionable, which makes our suggestion of the migration of Mg2+ a feasible alternative mechanism.

The structural analysis of other ribozymes, in particular the hammerhead, has suggested a direct interaction of Mg2+ with oxygen proRP, in contrast to the indirect interaction proposed for pistol ribozyme [23,24,25, 31, 32, 34, 36]. In the present study we observed a direct Mg2+—proRP oxygen interaction and assign the role of the acid to the O2’ of G32, making the proposed mechanism similar to the one suggested for the hammerhead ribozyme. Thus, the present study offers a new scenario to interpret the behaviour of the pistol ribozyme, but also suggests that more simulations are required to confirm the self-cleavage RNA reaction mechanism.

Data Availability

Cartesian coordinates of the active site of relevant structures are deposited as Electronic Supplementary Material.

Code Availability

5KTJ PDB structure can be downloaded from www.rcsb.org/structure/5KTJ. VMD v1.9.2 can be downloaded free of charge from www.ks.uiuc.edu/Research/vmd. NAMD v2.14 can be downloaded free of charge from www.ks.uiuc.edu/Research/namd. PROPKA3 v3.2 can be freely downloaded from github.com/jensengroup/propka. MOLDEN v5.8.1 can be downloaded under academic license from www3.cmbi.umcn.nl/molden. Antechamber is part of AmberTools20 that can be get from ambermd.org/AmberTools.php. Gaussian 09 D01 can be purchased from gaussian.com. fDYNAMO v2.2 can be freely downloaded from www.pdynamo.org/downloads

References

Prody GA, Bakos JT, Buzayan JM, Schneider IR, Bruening G (1986) Autolytic processing of dimeric plant-virus satellite RNA. Science 231:1577–1580

Buzayan JM, Gerlach WL, Bruening G (1986) Nonenzymatic cleavage and ligation of RNAs complementary to a plant-virus satellite RNA. Nature 323:349–353

Sharmeen L, Kuo MYP, Dintergottlieb G, Taylor J (1988) Antigenomic RNA of human hepatitis delta-virus can undergo self-cleavage. J Virol 62:2674–2679

Saville BJ, Collins RA (1990) A site-specific self-cleavage reaction performed by a novel RNA in Neurospora mitochondria. Cell 61:685–696

Winkler WC, Nahvi A, Roth A, Collins JA, Breaker RR (2004) Control of gene expression by a natural metabolite- responsive ribozyme. Nature 428:281–286

Roth A, Weinberg Z, Chen AGY, Kim PB, Ames TD, Breaker RR (2014) A widespread self-cleaving ribozyme class is revealed by bioinformatics. Nat Chem Biol 10:56–60

Weinberg Z, Kim PB, Chen TH, Li SS, Harris KA, Lunse CE, Breaker RR (2015) New classes of self-cleaving ribozymes revealed by comparative genomics analysis. Nat Chem Biol 11:606–610

Wilson TJ, Liu Y, Lilley DMJ (2016) Ribozymes and the mechanisms that underline RNA catalysis. Front Chem Sci Eng 10:178–185

Emilsson GM, Nakamura S, Roth A, Breaker RR (2003) Ribozyme speed limits. RNA 9:907–918

Bingaman JL, Gonzalez IY, Wang B, Bevilacqua PC (2017) Activation of the glmS ribozyme nucleophile via overdetermined hydrogen bonding. Biochemistry 56:4313–4317

Bingaman JL, Zhang S, Stevens DR, Yennawar NH, Hammes-Schiffer S, Bevilacqua PC (2017) The GlcN6P cofactor plays multiple catalytic roles in the glmS ribozyme. Nat Chem Biol 13:439–445

Seith DD, Bingaman JL, Veenis AJ, Button AC, Bevilacqua PC (2018) Elucidation of catalytic strategies of small nucleolytic ribozymes from comparative analysis of active sites. ACS Catal 8:314–327

Bevilacqua PC, Harris ME, Piccirilli JA, Gaines C, Ganguly A, Kostenbader K, Ekesan S, York DM (2019) An ontology for facilitating discussion of catalytic strategies of RNA-cleaving enzymes ACS Chem. Biol 14:1068–1076

Murray JB, Seyhan AE, Walter NG, Burke JM, Scott WG (1998) The hammerhead, hairpin and VS ribozymes are catalytically proficient in monovalent cations alone. Chem Biol 5:587–595

Golden BL (2011) Two distinct catalytic strategies in the hepatitis delta virus ribozyme cleavage reaction. Biochemistry 50:9424–9433

Mir A, Chen J, Robinson K, Lendy E, Goodman J, Neau D, Golden BL (2015) Two divalent metal ions and conformational changes play roles in the hammerhead ribozyme cleavage reaction. Biochemistry 54:6369–6375

Gaines CS, York DM (2016) Ribozyme catalysis with a twist: active state of the twister ribozyme in solution predicted from molecular simulation. J Am Chem Soc 138:3058–3065

Wilson TJ, Liu Y, Domnick C, Kath-Schorr S, Lilley DMJ (2016) The novel chemical mechanism of the twister ribozyme. J Am Chem Soc 138:6151–6162

Ren A, Kosutic M, Rajashankar KR, Frener M, Santner T, Westhof E, Micura R, Patel DJ (2014) In-line alignment and Mg2+ coordination at the cleavage site of the env22 twister ribozyme. Nat Comm 5:5534–5543

Ucisik MN, Bevilacqua PC, Hammes-Schiffer S (2016) Molecular dynamics study of twister ribozyme: role of Mg2+ ions and the hydrogen-bonding network in the active site. Biochemistry 55:3834–3846

Chen H, Giese TJ, Golden BL, York DM (2017) Divalent metal ion activation of a guanine general base in the hammerhead ribozyme: insights from molecular simulations. Biochemistry 56:2985–2994

Zhang S, Stevens DR, Goyal P, Bingaman JL, Bevilacqua PC, Hammes-Schiffer S (2016) Assessing the potential effects of active site Mg2+ ions in the glmS ribozyme-cofactor complex. J Phys Chem Lett 7:3984–3988

Ren A, Vušurović N, Gebetsberger J, Gao P, Juen M, Kreutz C, Micura R, Patel DJ (2016) Pistol ribozyme adopts a pseudoknot fold facilitating site-specific in-line cleavage. Nat Chem Biol 12:702–708

Nguyena LA, Wanga J, Steitz TA (2017) Crystal structure of Pistol, a class of self-cleaving ribozyme. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 114:1021–1026

Harris KA, Lünse CE, Li S, Brewer KI, Breaker RR (2016) Biochemical analysis of pistol self-cleaving ribozymes. RNA 21:1852–1858

Neuner S, Falschlunger C, Fuchs E, Himmelstoss M, Ren A, Patel DJ, Micura R (2017) Atom-specific mutagenesis reveals structural and catalytic roles for an active-site adenosine and hydrated Mg2+ in pistol ribozymes. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 56:15954–15958

Lee K-Y, Lee B-J (2017) Structural and biochemical properties of novel self-cleaving ribozymes. Molecules 22:678–695

Ren A, Micura R, Patel DJ (2017) Structure-based mechanistic insights into catalysis by small self-cleaving ribozymes. Curr Opin Chem Biol 41:71–83

Gebetsberger J, Micura R (2017) Unwinding the twister ribozyme: from structure to mechanism. WIR RNA 8:e1402

Mir A, Golden BL (2016) Two active site divalent ions in the crystal structure of the hammerhead ribozyme bound to a transition state analogue. Biochemistry 55:633–636

Wilson TJ, Liu Y, Li N-S, Dai Q, Piccirilli JA, Lilley J, D. M. (2019) Comparison of the structures and mechanisms of the pistol and hammerhead ribozymes. J Am Chem Soc 14:7865–7875

Teplova M, Falschlunger C, Krasheninina O, Egger M, Ren A, Patel DJ, Mivcura R (2020) Crucial roles of two hydrated Mg2+ ions in reaction catalysis of the pistol ribozyme. Angew Chem Int Ed 59:2837–2843

Panteva MT, Dissanayake T, Chen H, Radak BK, Kuechler ER, Giambasu GM, Lee T-S, York DM (2015) Multiscale methods for computational RNA enzymology. Method Enzymol 533:335–374

Kostenbader K, York DM (2019) Molecular simulations of the pistol ribozyme: unifying the interpretation of experimental data and establishing functional links with the hammerhead ribozyme. RNA 25:1439–1456

Ganguly A, Weissman BJ, Piccirilli JA, York DM (2019) Evidence for a catalytic strategy to promote nucleophile activation in metal-dependent RNA-cleaving ribozymes and 8–17 DNAzyme. ACS Catal 9:10612–20617

Roy RN, Joseph NN, Steitz TA (2020) Molecular dynamics analysis of Mg2+-dependent cleavage of a pistol ribozyme reveals a fail-safe secondary ion for catalysis. J Comput Chem 14:1345–1352

Case DA, Aktulga HM, Belfon K, Ben-Shalom IY, Brozell SR, Cerutti DS, Cheatham TE III, Cruzeiro V, Darden TA, Duke RE, Giambasu G, Gilson MK, Gohlke H, Goetz AW, Harris R, Izadi S, Izmailov SA, Jin C, Kasavajhala K, Kaymak MC, King E, Kovalenko A, Kurtzman T, Lee TS, LeGrand S, Li P, Lin C, Liu J, Luchko T, Luo R, Machado M, Man V, Manathunga M, Merz KM, Miao Y, Mikhailovskii O, Monard G, Nguyen H, O’Hearn KA, Onufriev A, Pan F, Pantano S, Qi R, Rahnamoun A, Roe DR, Roitberg A, Sagui C, Schott-Verdugo S, Shen J, Simmerling CL, Skrynnikov NR, Smith J, Swails J, Walker RC, Wang J, Wei H, Wolf RM, Wu X, Xue Y, York DM, Zhao S, Kollman PA (2021) Amber 2021. San Francisco, University of California

Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML (1983) Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J Chem Phys 79:926–935

Allnér O, Nilsson L, Villa A (2012) Magnesium ion-water coordination and exchange in biomolecular simulations. J Chem Theory Comput 8:1493–1502

Wang J, Wang W, Kollman PA, Case DA (2006) Automatic atom type and bond type perception in molecular mechanical calculations. J Mol Graph Model 25:247–260

Phillips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, Villa E, Chipot C, Skeel RD, Kalé L, Schulten K (2005) Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J Comput Chem 26:1781–1802

Wang J, Cieplak P, Kollman PA (2000) How well does a restrained electrostatic potential (RESP) model perform in calculating conformational energies of organic and biological molecules? J Comput Chem 21:1049–1074

Pérez A, Marchán I, Svozil D, Sponer J, Cheatham TE, Laughton CA, Orozco M (2007) Refinement of the AMBER force field for nucleic acids: improving the description of alpha/gamma conformers. Biophys J 92:3817–3829

Zgarbová M, Otyepka M, Sponer J, Mládek A, Banáš P, Cheatham TE, Jurečka, P.Refinement of the Cornell, et al (2011) Nucleic acids force field based on reference quantum chemical calculations of glycosidic torsion profiles. J Chem Theory Comput 7:2886–2902

Steinbrecher T, Latzer J, Case DA (2012) Revised AMBER parameters for bioorganic phosphates. J Chem Theory Comput 8:4405–4412

Martyna GJ, Tobias DJ, Klein ML (1994) Constant pressure molecular dynamics algorithms. J Chem Phys 101:4177–4189

Grest GS, Kremer K (1986) Molecular dynamics simulation for polymers in the presence of a heat bath. Phys Rev A 33:3628–3631

Imhof P, Noé F, Fischer S, Smith JC (2006) AM1/d Parameters for Magnesium in Metalloenzymes. J Chem Theory Comput 2:1050–1056

Nam K, Cui Q, Gao J, York DM (2007) Specific reaction parametrization of the AM1/d hamiltonian for phosphoryl transfer reactions: H, O, and P atoms. J Chem Theory Comput 3:486–504

Field MJ, Albe M, Bret C, Proust-De Martin F, Thomas A (2000) The dynamo library for molecular simulations using hybrid quantum mechanical and molecular mechanical potentials. J Comput Chem 21:1088–1100

Krzemińska A, Paneth P, Moliner V, Świderek K (2015) Binding isotope effects as a tool for distinguishing hydrophobic and hydrophilic binding sites of HIV-1 RT. J Phys Chem B 119:917–927

Świderek K, Marti S, Tuñón I, Moliner V, Bertran J (2015) Peptide bond formation mechanism catalyzed by ribosome. J Am Chem Soc 137:12024–12034

Martí S, Moliner V, Tuñón I (2005) Improving the QM/MM description of chemical processes: a dual level strategy to explore the potential energy surface in very large systems. J Chem Theory Comput 1:1008–1016

Martí S (2020) QMCube (QM3): An all-purpose suite for multiscale QM/MM calculations. J Comput Chem 42:447–457

Zhao Y, Truhlar DG (2008) The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: Two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other function. Theor Chem Acc 120:215–241

Gaines CS, York DM (2017) Model for the functional active state of the TS ribozyme from molecular simulation. Angew Chem Int Ed 56:13392–13395

Heldenbrand H, Janowski PA, Giambaşu G, Giese TJ, Wedekind JE, York DM (2014) Evidence for the role of active site residues in the hairpin ribozyme from molecular simulations along the reaction path. J Am Chem Soc 136:7789–7792

Świderek K, Marti S, Tuñón I, Moliner V, Bertran J (2017) Molecular mechanism of the site-specific self-cleavage of the RNA phosphodiester backbone by a twister ribozyme. J Theor Chem Acc 136:31

Martí S, Bastida A, Świderek K (2019) Theoretical studies on mechanism of inactivation of kanamycin A by 4’-O-Nucleotidyltransferase. Front Chem 6:660

Lihanova Y, Weinberg CE (2021) Biochemical analysis of cleavage and ligation activities of the pistol ribozyme from Paenibacillus polymyxa. RNA Biol. https://doi.org/10.1080/15476286.2021.1874706

Torres RA, Himo F, Bruice TC, Noodleman L, Lovell T (2003) Theoretical examination of Mg2+-mediated hydrolysis of a phosphodiester linkage as proposed for the hammerhead ribozyme. J Am Chem Soc 125:9861–9867

Leclerc F, Karplus M (2006) Two-metal-ion mechanism for hammerhead-ribozyme catalysis. J Phys Chem B 110:3395–3409

Nakano S, Chadalavada DM, Bevilacqua PC (2000) General acid-base catalysis in the mechanism of a hepatitis delta virus ribozyme. Science 287:1493–1497

Liu Y, Wilson TJ, Lilley DM (2017) The structure of a nucleolytic ribozyme that employs a catalytic metal ion. Nat Chem Biol 13:508–513

Wong K-Y, Lee T-S, York DM (2011) Active participation of the Mg2+ ion in the reaction coordinate of RNA self-cleavage catalyzed by the hammerhead ribozyme. J Chem Theory Comput 7:1–3

Mlýnský V, Walter NG, Šponer J, Otyepka M, Banáš P (2015) The role of an active site Mg2+ in HDV ribozyme self-cleavage: insights from QM/MM calculations. Phys Chem Chem Phys 17:670–679

Lee T-S, López CS, Martick M, Scott WG, York DM (2007) Insight into the role of Mg2+ in hammerhead ribozyme catalysis from X-ray crystallography and molecular dynamics simulation. J Chem Theory Comput 3:325–327

Lee T-S, Silva López C, Giambasu GM, Martick M, Scott WG, York DM (2008) Role of Mg2+ in hammerhead ribozyme catalysis from molecular simulation. J Am Chem Soc 130:3053–3064

Leonarski F, D’Ascenzo L, Auffinger P (2017) Mg2+ ions: do they bind to nucleobase nitrogens? Nucleic Acid Res 43:987–1004

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (PGC2018- 094852-B-C21, PGC2018-094852-B-C22 and PID2019-107098RJ-I00), the Generalitat Valenciana (Grant AICO/2019/195 and SEJI/2020/007) and Universitat Jaume I (Grant UJI-B2020-03 and UJI-A2019-04). N.S-A. thanks to the MINECO for the doctoral FPI grant (BES-2016-078029). Authors acknowledge computational resources from the Servei d’Informàtica of Universitat Jaume I.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

11244_2021_1494_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Supplementary file1 (DOCX 2028 KB) Parameters for guanine nucleobase deprotonated in N1 and guanine nucleobaseprotonated in N3; time evolution of key geometrical variables along the 50 ns MDsimulations starting from model M3; transition state structures optimized at M06-2X/MMlevel; Cartesian coordinates of the active site of relevant structures

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Serrano-Aparicio, N., Świderek, K., Tuñón, I. et al. Theoretical Studies of the Self Cleavage Pistol Ribozyme Mechanism. Top Catal 65, 505–516 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11244-021-01494-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11244-021-01494-1