Abstract

Objectives

Our study addresses the question: Does providing inmates with education while incarcerated reduce their chances of recidivism and improve their postrelease employment prospects?

Methods

We aggregated 37 years of research (1980–2017) on correctional education and applied meta-analytic techniques. As the basis for our meta-analysis, we identified a total of 57 studies that used recidivism as an outcome and 21 studies that used employment as an outcome. We then applied random-effects regression across the effect sizes abstracted from each of these studies.

Findings

When focusing on studies with the highest caliber research designs, we found that inmates participating in correctional education programs were 28% less likely to recidivate when compared with inmates who did not participate in correctional education programs. However, we found that inmates receiving correctional education were as likely to obtain postrelease employment as inmates not receiving correctional education.

Conclusion

Our meta-analysis demonstrates the value in providing inmates with educational opportunities while they serve their sentences if the goal of the program is to reduce recidivism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Duguid (1982) provides limited discussion of sociopolitical development; we do not include this last component in our discussion here.

Despite the empirical rigor of this study, it is excluded from our own meta-analysis as our focus is solely on correctional education programs administered in the USA.

Databases included the Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), Education Abstracts Criminal Justice Abstracts, National Criminal Justice Reference Service Abstracts, Academic Search Elite, EconLit, Sociological Abstracts, Google Scholar, and the Rutgers Library of Criminal Justice Grey Literature Database.

Online repositories included the Vera Institute of Justice, Urban Institute, Washington State Institute for Public Policy, American Institutes for Research, Mathematica Policy Research, John Jay College of Criminal Justice Re-entry Institute, Justice Policy Institute, Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP), Juvenile Justice Educational Enhancement Program (JJEEP), RTI International, and Manpower Demonstration Research Corporation (MDRC).

In cases where multiple versions of the same paper were identified, such as when a conference presentation later becomes a peer-reviewed article, we used the most recent version of the study. In a few cases, there were multiple studies by the same author(s) that used variations of the same sample. In those cases, we chose the version of the study that had the broadest sample (e.g., all prisoners released between 1990 and 1995 rather than all prisoners released between 1990 and 1992).

Intent-to-treat analysis most closely reflects a practical program implementation scenario because it incorporates noncompliance and protocol deviations, which are common features of many prisoner rehabilitation programs. Additionally, intent-to-treat analysis maintains the initial balance of inmate characteristics generated from the original assignment to treatment or control in cases where there is assignment (Gupta 2011).

Our aggregation of multiple types of recidivism and time periods is based on the assumption that the estimated effect of correctional education is not contingent on the measurement strategy or specification used by the researcher. We tested this assumption by sampling studies that reported the effects of correctional education on recidivism using consistent definitions and time periods, and estimated our models on these limited subsamples with consistent metrics. We found that the effect of correctional education did not differ across the definition of recidivism (e.g., reincarceration, rearrest, parole failure) or time period used (e.g., 6 months since release from prison, 1 year since release from prison, 10 years since release from prison). This gives us confidence that the findings from our meta-analysis are robust and apply to a range of postrelease settings, circumstances, and outcomes. It is worth noting that the previous meta-analyses faced similar limitations due to variation in metrics reported by the study authors; our aggregation approach is in line with how the previous meta-analyses empirically dealt with this limitation. Without this aggregation approach, it would be impossible to apply meta-analytic methods to the study of correctional education due to the heterogeneity in measurement approaches.

It is not possible to discern the total number of studies that include female inmates in their samples due to inconsistencies in reporting. For a more detailed discussion of women’s participation in correctional education, see Rose (2004).

We computed robust standard errors for meta-regression using the ROBUMETA command available in Stata (Hedberg 2011). This was necessary only for our analysis of recidivism, as there was not sufficient nesting in the pool of eligible studies of employment to permit this computation. The results were not contingent on the method for estimating the standard errors; tests of significance reflect unadjusted standard errors.

Note that the last row, which includes the pooled effect size for levels 2, 3, 4, and 5, is the same as the pooled effect size for the total sample because they both are based on all 57 studies.

References

Andrews, D. A., & Bonta, J. (2010). The psychology of criminal conduct. London: Routledge.

Andrews, D. A., & Dowden, C. (2007). The risk-need-responsivity model of assessment and human service in prevention and corrections: crime-prevention jurisprudence. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 49(4), 439–464.

Andrews, D. A., Zinger, I., Hoge, R. D., Bonta, J., Gendreau, P., & Cullen, F. T. (1990a). Does correctional treament work? A clinically relevant and psychologically informed meta-analysis. Criminology, 28(3), 369–404.

Andrews, D. A., Bonta, J., & Hoge, R. D. (1990b). Classification for effective rehabilitation: rediscovering psychology. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 17(1), 19–52.

Aos, S., Miller, M., & Drake, E. (2006). Evidence-based adult correction programs: what works and what does not. Olympia: Washington State Institute for Public Policy.

Arbuthnot, J. (1984). Moral reasoning development programs in prison: cognitive development and critical reasoning approaches. Journal of Moral Education, 13(2), 108–119.

Arbuthnot, J., & Gordon, D. A. (1983). Moral reasoning development in correctional intervention. Journal of Correctional Education, 34(4), 133–138.

Berman, J. J. (1973). Parollees’ problems, aspirations and attitudes. Evanston: Northwestern University.

Bonta, J., & Andrews, D. A. (2007). Risk-need-responsivity model for offender assessment and rehabilitation. Ottawa, Canada: Public Safety Canada.

Bonta, J., & Gendreau, P. (1990). Reexamining the cruel and unusual punishment of prison life. Law and Human Behavior, 14(4), 347–372.

Bushway, S., & Reuter, P. (2002). Labor markets and crime risk factors. In D. P. Farrington, D. L. Mackenzie, L. Sherman, & B. C. Welsh (Eds.), Evidence-based crime prevention. New York: Routledge.

Clear, T. R., Rose, D. R., Waring, E., & Scully, K. (2003). Coercive mobility and crime: a preliminary examination of concentrated incarceration and social disorganization. Justice Quarterly, 20(1), 33–64.

Cronin, J. (2011). The path to successful reentry: the relationship between correctional education, employment and recidivism. Columbia: University of Missouri, Institute of Public Policy.

Cullen, F. T. (1994). Social support as an organizing concept for criminology: presidential address to the academy of criminal justice sciences. Justice Quarterly, 11(4), 527–559.

Davis, L. M., Bozick, R., Steele, J. L., Saunders, J., & Miles, J. N. V. (2013). Evaluating the effectiveness of correctional education: a meta-analysis of programs that provide education to incarcerated adults. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation.

Davis, Lois M., Jennifer L. Steele, Robert Bozick, Malcom V. Williams, Susan Turner, Jeremy N.V. Miles, Jessica Saunders, and Paul S. Steinberg. 2014. How effective is correctional education, and where do we go from here? The results of a comprehensive evaluation. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Duguid, S. (1982). Rehabilitation through education: a Canadian model. Journal of Offender Counseling Services Rehabilitation, 6(1–2), 53–67.

Duwe, G., & Clark, V. (2014). The effects of prison-based educational programming on recidivism and employment. The Prison Journal, 94(4), 454–478.

Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in metaanalysis detected by a simple, graphical test. British Medical Journal, 9(4), 28–35.

Farrington, David P., Jeremy W. Coid, Louise M. Harnett, Darrick Jolliffe, Nadine Sateriou, Richard E. Turner, and Donald J. West. 2006. Criminal careers up to age 50 and life success up to age 48: new findings from the Cambridge study in delinquent development (2nd ed.). London: Home Office Research, Development and Statistics Directorate.

Gerber, J., & Fritsch, E. J. (1995). Adult academic and vocational correctional education programs: a review of recent research. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 22(1/2), 119–142.

Goff, A., Rose, E., Rose, S., & Purves, D. (2007). Does PTSD occur in sentenced prison populations? A systematic literature review. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 17(3), 152–162.

Gorgol, L. E., & Sponsler, B. A. (2011). Unlocking potential: results of a national survey of postsecondary education in state prisons. Issue brief. Washington, DC: Institute for Higher Education Policy.

Greenberg, E., Dunleavy, E., & Kutner, M. (2007). Literacy behind bars: results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy Prison Survey. NCES 2007-473. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

Gupta, S. K. (2011). Intention-to-treat concept: a review. Perspectives in Clinical Research, 2(3), 109–112.

Harer, M. D. (1995). Prison education program participation and recidivism: a test of the normalization hypothesis. Washington, DC: Federal Bureau of Prisons, Office of Research and Evaluation.

Hedberg, Eric C. (2011). ROBUMETA: Stata module to perform robust variance estimation in meta-regression with dependent effect size estimates, working paper.

Hedges, L. V., Tipton, E., & Johnson, M. C. (2010). Robust variance estimation in meta-regression with dependent effect size estimates. Research Synthesis Methods, 1(1), 39–65.

Hill, L., Scaggs, S. J. A., & Bales, W. D. (2017). Assessing the statewide impact of the Specter Vocational Program on reentry outcomes: a propensity score matching analysis. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 56(1), 61–86.

Kim, R. H., & Clark, D. (2013). The effect of prison-based college education programs on recidivism. Journal of Criminal Justice, 41, 196–204.

Kohlberg, L. (1963). The development of children’s orientations toward a moral order. Human Development, 6(1–2), 11–33.

Landenberger, N. A., & Lipsey, M. W. (2005). The positive effects of cognitive–behavioral programs for offenders: a meta-analysis of factors associated with effective treatment. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 1(4), 451–476.

Langan, Patrick A., and David J. Levin. 2002. Recidivism of prisoners released in 1994 Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Langenbach, M., North, M. Y., Aagaard, L., & Chown, W. (1990). Televised instruction in Oklahoma prisons: a study of recidivism and disciplinary actions. Journal of Correctional Education, 41(2), 87–94.

Lattimore, P. K., Witte, A. D., & Baker, J. R. (1988). Sandhills vocational delivery system experiment: an examination of correctional program implementation and effectiveness. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice.

Lattimore, P. K., Witte, A. D., & Baker, J. R. (1990). Experimental assessment of the effect of vocational training on youthful property offenders. Evaluation Review, 14(2), 115–133.

Laub, J. H., & Sampson, R. J. (2003). Shared beginnings, divergent lives: delinquent boys to age 70. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Linden, R., Perry, L., Ayers, D., & Parlett, T. A. A. (1984). An evaluation of a prison education program. Canadian Journal of Criminology, 26, 65–73.

Lipsey, M. W. (2009). The primary factors that characterize effective interventions with juvenile offenders: a meta-analytic overview. Victims and Offenders, 4(2), 124–147.

Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (1993). The efficacy of psychological, educational, and behavioral treatment: confirmation from meta-analysis. American Psychologist, 48(12), 1181–1209.

Lockwood, S., Nally, J. M., Ho, T., & Knutson, K. (2012). The effect of correctional education on postrelease employment and recidivism: a 5-year follow-up study in the state of Indiana. Crime & Delinquency, 58(3), 380–396.

MacKenzie, D. L. (2006). What works in corrections: reducing the criminal activities of offenders and delinquents. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Maruna, S., & LeBel, T. P. (2010). The desistance paradigm in correctional practice: from programmes to lives. In F. McNeill, P. Raynor, & C. Trotter (Eds.), Offender supervision: new directions in theory, research and practice (pp. 65–89). Cullompton: Willan.

Murray, Joseph, David P. Farrington, Ivana Sekol, and Rikke F. Olsen. 2009. Effects of parental imprisonment on child antisocial behaviour and mental health: a systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews 2009(4).

Pettit, B. (2012). Invisible men: mass incarceration and the myth of black progress. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Pew Center on the States. (2011). State of recidivism: the revolving door of America’s prisons. Washington, DC: The Pew Charitable Trusts.

Piaget, J. (1997). The moral judgement of the child. Glencoe, IL: The Free Press.

Piehl, A. M. (1995). Learning While Doing Time, Kennedy School Working Paper #R94-25. Boston, MA: Harvard University.

Pompoco, A., Wooldredge, J., Lugo, M., Sullivan, C., & LaTessa, E. (2017). Reducing inmate misconduct and prison retures with facility education programs. Criminology and Public Policy, 16(2), 515–547.

Rose, C. (2004). Women’s participation in prison education: what we know and what we don’t know. Journal of Correctional Education, 55(1), 78–100.

Sabol, W. J. (2007). Local labor market conditions and post-prison employment: evidence from Ohio. In S. Bushway, M. A. Stoll, & D. F. Weiman (Eds.), Barriers to reentry? The labor market for released prisoners in post-industrial America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Sabol, W. J., & Lynch, J. P. (2003). Assessing the longer-run consequences of incarceration: effects on families and employment. Contributions in Criminology and Penology, 55, 3–26.

Saylor, W. G., & Gaes, G. G. (1997). Training inmates through industrial work participation, and vocational and apprenticeship instruction. Corrections Management Quarterly, 1(2), 32–43.

Schnittker, J., & John, A. (2007). Enduring stigma: the long-term effects of incarceration on health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 48(2), 115–130.

Sherman, L., Gottfredson, D. C., MacKenzie, D. L., Eck, J., Reuter, P., & Bushway, S. D. (1997). Preventing crime: what works, what doesn’t, what’s promising. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs.

Travis, J., Western, B., & Redburn, S. (2014). The growth of incarceration in the United States: exploring causes and consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Turner, Susan F. (2018). Multiple faces of reentry. In J. Wooldridge, & P. Smith (Eds.), Oxford handbook on prisons and punishment. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Uggen, C. (2000). Work as a turning point in the life course of criminals: a duration model of age, employment and recidivism. American Sociological Review, 65, 529–546.

Uggen, C., Manza, J., & Thompson, M. (2006). Citizenship, democracy, and the civic reintegration of criminal offenders. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 605(1), 281–310.

Visher, C., Winterfield, L., & Coggeshall, M. B. (2005). Ex-offender employment programs and recidivism: a meta-analysis. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 1(3), 295–315.

Western, B. (2006). Punishment and inequality in America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Wildeman, C., Wakefield, S., & Turney, K. (2013). Misidentifying the effects of parental incarceration? A comment on Johnson and Easterling (2012). Journal of Marriage and Family, 75(1), 252–258.

Wilson, D. B., Gallagher, C. A., & MacKenzie, D. L. (2000). A meta-analysis of corrections-based education, vocation, and work programs for adult offenders. Journal of Research in Crime & Delinquency, 37(4), 347–368.

Winterfield, L., Coggeshell, M., Burke-Storer, M., Correa, V., & Tidd, S. (2009). The effects of postsecondary correctional education: final report. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute.

Funding

This research was conducted with support from a grant from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance (2010-RQ-BX-0001). All analyses and interpretations are the authors alone.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

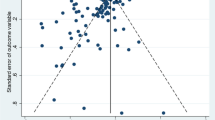

Forest plots

In this appendix, we present two forest plots: one for the recidivism analysis and one for the employment analysis. Each row in the plot corresponds to an effect size, labeled on the left with the corresponding first author of the study and the year of publication. Studies with multiple effect sizes are listed multiple times with a capital letter to differentiate among them. The black box represents the effect size estimate for the study, and the “whiskers” extend to the range of 95% confidence intervals. The box and whiskers for each effect size are plotted in relation to the dashed line down the center of the graph, which indicates an odds ratio of 1. Effect sizes to the right of this line indicate that the treatment group had a higher odds of recidivating (or being employed), and effect sizes to the left of this line indicate that the comparison group had a higher odds of recidivating (or being employed). If the whiskers for the corresponding box do not cross this dashed line, then the study yielded a significant difference between the treatment and comparison group for that particular effect size at the conventional level of p < 0.05. Conversely, if the whiskers for the corresponding box cross this dashed line, then there is no significant difference detected between the treatment and the comparison group for that particular effect size at the conventional level of p < 0.05.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bozick, R., Steele, J., Davis, L. et al. Does providing inmates with education improve postrelease outcomes? A meta-analysis of correctional education programs in the United States. J Exp Criminol 14, 389–428 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-018-9334-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-018-9334-6