ABSTRACT

Purpose

The third most frequently diagnosed cancer in Europe in 2018 was lung cancer; it is also the leading cause of cancer death in Europe. We studied patient and tumor characteristics, and patterns of healthcare provision explaining regional variability in lung cancer survival in southern Spain.

Methods

A population-based cohort study included all 1196 incident first invasive primary lung cancer (C33–C34 according to ICD-10) cases diagnosed between 2010 and 2011 with follow-up until April 2015. Data were drawn from local population-based cancer registries and patients’ hospital medical records from all public and private hospitals from two regions in southern Spain.

Results

There was evidence of regional differences in lung cancer late diagnosis (58% stage IV in Granada vs. 65% in Huelva, p value < 0.001). Among patients with stage I, only 67% received surgery compared with 0.6% of patients with stage IV. Patients treated with a combination of radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and surgery had a 2-year mortality risk reduction of 94% compared with patients who did not receive any treatment (excess mortality risk 0.06; 95% CI 0.02–0.16). Geographical differences in survival were observed between the two regions: 35% vs. 26% at 1-year since diagnosis.

Conclusions

The observed geographic differences in survival between regions are due in part to the late cancer diagnosis which determines the use of less effective therapeutic options. Results from our study justify the need for promoting lung cancer early detection strategies and the harmonization of the best practice in lung cancer management and treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lung cancer was the third most frequently diagnosed cancer in Europe in 2018 with 364,601 new cases [1]. In Spain, it is estimated that 28,347 new lung cancer cases were diagnosed in 2015. Lung cancer is the third most frequently diagnosed cancer in men after prostate and colorectal cancer; and the fourth in females after breast, colorectal, and endometrial cancer [2], excluding non-melanoma skin cancer. Moreover, lung cancer was the leading cause of cancer death among males in 2012 worldwide [3] with 1,590,000 deaths of lung cancer, accounting for 87% of the mortality from cancer and making it the leading cause of cancer death in the world [4].

Despite improvements in lung cancer biology and the increased diagnostic and therapeutic effort in recent decades, lung cancer still has one of the world’s lowest survival [5]. The European mean age-standardized 5-year relative survival for male lung cancer patients diagnosed in 2000–2007 was 12.0% and 15.9% for female patients [6]. Lung cancer survival in Spain had a poor prognosis, with a 5-year relative survival of 10.6% (95% CI 10.1–11.2) [7].

Patient and tumor characteristics are important drivers of lung cancer survival. For instance, smoking behavior varies significantly between individuals and populations reflecting geographical and temporal variability in lung cancer incidence [8]. Lung cancer survival among smokers is lower than that of non-smokers, but the effect of tobacco on lung cancer survival could be mediated by comorbidity associated with smoke [9, 10]. Furthermore, stage, age at diagnosis, and cancer treatment are the most important determinants of lung cancer survival [9]. Current evidence suggests the importance of an early diagnosis to allow a better lung cancer prognosis [6, 11, 12]. However, it is still difficult to make an early diagnosis of lung cancer [13, 14]. Furthermore, differences in patterns of healthcare may explain regional variability in lung cancer survival.

Recently, regional variability in lung cancer survival has been found in Spain [15]. We hypothesized that the regional variability in lung cancer survival could be characterized by patient, tumor, and healthcare provision determinants [16]. Characterizing factors associated with regional differences in lung cancer survival is extremely important for public health professionals and policymakers as it can help them to allocate resources and develop strategies to reduce survival inequalities. We studied the distribution and frequency of patient, tumor, and healthcare provision factors, their regional variability, and their association with lung cancer survival in southern Spain.

Methods: study design

We develop a population-based cohort study including 1196 incident lung cancer cases from two population-based cancer registries in southern Spain (Huelva and Granada) following international standard procedures and coding rules (http://www.hrstudies.eu/). Both cancer registries follow the international recommendations by the IARC (International Agency for Research on Cancer) and the ENCR (European Network of Cancer Registries) from the beginning of their activity (Granada from 1985 and Huelva from 2007). The cancer registry from Huelva is more recent than Granada. However, it has consolidated data of all anatomical sites since 2007 and has published their incidence results elsewhere [17].

Cases were diagnosed with a first invasive primary lung cancer [C33–C34 according to International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition, (ICD-O-3)] between 2010 and 2011 with follow-up until April 2015. Cancer registry data related to patients’ sociodemographic and basic tumor characteristics were enhanced with information from hospital medical records including cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Variables included in the study

We included the date of cancer diagnosis from cancer registration data and patients’ date of death at the end of follow-up extracted from the National Death Index. The vital status “alive” was then validated with the information from patients’ hospital medical records. In addition to basic sociodemographic patient data, the date of diagnosis and the vital status, we characterized the information obtained from the medical records as patient, tumor, and healthcare provision factors.

Patient’s characteristics

We included age, gender, smoking status, and comorbidities including 19 diseases. Age at diagnosis was categorized into five age groups: 15–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74 and ≥ 75 years. Smoking status was categorized as the current, past, and never smoker. Comorbidities were included using the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) and coded according to the number of comorbidity conditions: no comorbidity (0–1 points), low comorbidity (2 points), high comorbidity (> 2 points), and unknown [18, 19].

Tumor factors

We included the presence of a previous lung disease, tumor topography, morphology, laterality, and stage at diagnosis. The final stage variable was defined as the combination of clinical and pathological TNM and categorized into five groups based on the 7th edition of the TNM manual: stage I–IV, and unknown. Topography and morphology (defined later) were coded according to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition (ICD-O-3).

Healthcare provision factors

We included diagnosis type and treatment information from medical records. The method of diagnosis was categorized as clinical/instrumental only, cytological, or histological (including histological diagnosis of metastasis). The clinical category included chest X-ray, spiral computed tomography (CT), positron emission tomography (PET), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), bronchoscopy, endobronchial ultrasound-guided bronchoscopy (EBUS), and mediastinoscopy. If the diagnosis was based on a cytological or a histological evaluation, the disease was considered microscopically verified and was further classified by morphology: adenocarcinoma (ADC), squamous cells carcinoma (SqCC), small cells carcinoma (SmCC), large cells carcinoma (LCC), and other types. Both microscopically verified and unverified lung cancer cases were included. First treatment information was classified into four different categories: surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted treatment, and their combination. We also included the time to first treatment as the time elapsed between the date of diagnosis and the date of the first treatment. Palliative care was defined as the treatment administered without curative intent and patients who did not receive surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted treatment, and their combination were classified as untreated.

Statistical analysis

To describe regional variability related to the patient’s tumor, diagnostic procedures, and treatment characteristics, we used counts and proportions. To assess the strength of the statistical differences between regions, we used the Chi-square test and the Fisher’s exact test when applicable. To describe the time to the first treatment, we used the median and the interquartile range (IQR). We used the region of analysis as a binary dependent variable with the province of Huelva as the reference to study regional variability in lung cancer treatment using logistic regression models for each of the treatment combinations. Odds of receiving treatment vs. non-treatment and each combination of treatment vs. any other therapy with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were computed. Models were adjusted for age, morphology, and stage at diagnosis. Then, to compare differences in the time to the first treatment by regions, we used the non-parametric Mann–Whitney test.

Finally, to investigate lung cancer survival by regions, we estimate 1- and 2-year age-standardized net survival using the Pohar Perme estimator [20]. To estimate the net survival, we used population regional life tables broken down by sex and categories of age [21]. For the standardization of the net survival by age, we used the standard cancer patient population and 95% CI were derived based on the delta method. Finally, we investigated regional variability in excess mortality due to cancer estimating excess mortality risks (EMR) using multivariable generalized linear models with a Poisson error structure [22]. We used Stata v. 14 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA) for the statistical analysis [23].

Results

Patient and tumor factors

Table 1 shows patient and tumor characteristics from 1196 incident cases of lung cancer in two southern Spanish provinces. The majority of the cases were men (83%) with a similar proportion in both regions. Age at diagnosis was significantly higher in Granada than in Huelva. Percentage of patients over 75 years old was 38% in Granada and 24% in Huelva. The percentage of non-smokers was lower in Huelva (10%) than in Granada (15%). For both regions, smoking in men was more frequent than in women (47% vs. 39%, data not shown); however, in Huelva, there was a greater percentage of women who smoke than in Granada (50% vs. 33%, data not shown). The presence of a previous pulmonary disease was more frequent in Huelva than Granada (55% vs. 37%), but the CCI showed higher comorbidity in Granada. Microscopic verification was obtained in 80% of cases with a higher proportion in Huelva than Granada (85% vs. 76%). Significant differences between the two regions were found regarding morphology, i.e., the most frequent histological type in Granada was adenocarcinoma (40%) but in Huelva it was squamous cell carcinoma (25%). Large cell carcinoma was much more frequent in Huelva than Granada (16% vs. 2%). Huelva showed a higher prevalence of stage IV at diagnosis than Granada (65% vs. 58%, p value < 0.001).

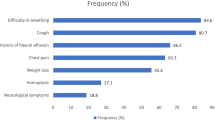

Diagnosis procedures, treatment characteristics, and time to the first treatment

Tables 2 and 3 show differences in health care provision factors between provinces. All diagnostic tests except CT and MRI were applied differentially in the two regions. Thoracic imaging and bronchoscopy were more frequently used in Huelva, whereas PET, mediastinoscopy, and EBUS were more frequently used in Granada (Table 2). Chemotherapy or radiotherapy was administered to a greater percentage of patients in the province of Huelva, while surgery or targeted therapy was applied in a similar proportion (Table 3).

Surgery was only indicated in 15% of all stages patients in both regions. For each stage, patients who received surgery were 81% with stage I, 55% with stage II, 11% with stage III and 2% with stage IV (data not shown). Our study shows that treatments containing surgery are performed in a very small percentage of patients in stage IV (0.9% radio + surgery, 0.3% chemo + surgery and 0.4% radio + chemo + surgery) (data not shown).

Forty percent of the patients in Granada and 32% in Huelva received treatment without curative intent. The first treatment with surgery or target treatment had similar percentages in both regions. There was a greater tendency in Huelva compared to Granada to administer only radiotherapy (13% vs. 5%), radiotherapy along with chemotherapy (24% vs. 16%) or the combination of radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and surgery (4% vs. 2%). In contrast, treatment with chemotherapy alone (20% vs. 14%) or surgery alone (10% vs. 6%) was more common in Granada (Table 3).

We found a greater probability of treatment with only radiotherapy in Huelva than in Granada (OR = 2.8; 95% CI 1.8–4.4), whereas in Granada the probability of performing only surgery (OR = 0.5; 95% CI 0.2–1.0) or only chemotherapy (OR = 0.5; 95% CI 0.4–0.8) was higher (Table 4).

The time elapsed from diagnosis to the first treatment was higher in Granada (median of 43 days; IQR 26–82 days) compared to Huelva (39 days; IQR 18–64 days) (p value < 0.001). Chemotherapy was the first therapeutic option both in Granada (first treatment administered in 35% of patients) and in Huelva [although with a lower percentage (29%)] followed by radiotherapy (24% in Huelva vs. 10% in Granada).

Age-standardized net survival and excess mortality risk

Survival was greater in Granada than in Huelva, in both men and women. 1-year net survival was 35% in Granada vs. 26% in Huelva, and 2-year net survival was 21% in Granada vs. 17% in Huelva. Survival in females was higher than males in the two regions, with percentages almost twice higher than males 2 years after diagnosis. Greater survival in Granada was observed in all age groups, although it was more pronounced between 45 and 64 years of age (Table 5). However, stratified analysis by cancer stage only showed a higher survival probability in Granada for patients with cancer stage IV, while in stages I–III Huelva obtained better indicators than Granada 2-year after diagnosis (Table 5).

Multivariable adjustment showed moderate evidence for higher excess cancer mortality in Huelva than Granada with 13% 2-year EMR of death (95% CI 0.97–1.30). All treatment combinations including surgery showed better survival than any other treatment combination without surgery. The most effective treatment regarding 2-year survival was the combination of radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and surgery, reducing the risk of death by 94% compared to patients who did not receive this combination of treatment (EMR = 0.06; 95% CI 0.02–0.16). Patients who were treated with a single therapeutic option other than surgery had a lower reduction in the risk of death compared to other treatments combinations (Table 6).

Discussion

The present population-based study analyzed lung cancer net survival in patients diagnosed in two southern Spanish regions and showed geographical differences of patient, tumor, and healthcare provision determinants associated with 1- and 2-year net survival probability (age-standardized 1-year net survival was 35% in Granada and 26% in Huelva). 1-year age-standardized net survival for lung cancer in southern Spain is lower than the overall Spanish 1-year age-standardized net survival, i.e., 38% (95% CI 37–38) and the European, 39% (95% CI 38.8–39.2) [15, 24]. Furthermore, we found that more than 50% of cases were diagnosed late (stage IV) and the prevalence of late diagnosis was different between the study regions (58% in Granada vs. 65% in Huelva).

The prevalence of tobacco smoking and lung disease was higher in Huelva than in Granada; patients in Huelva were younger and showed lower comorbidity, both which could mean a better prognosis concerning survival [25, 26]. However, although older age is associated with a worse prognosis, some studies show tumors in younger patients are more aggressive than in older patients, as has been observed in the present study. In this regard, Sacher et al. [27] conclude that younger age is associated with an increased likelihood of harboring a targetable genotype and the survival of young patients with that genotype is unexpectedly poor compared with other age groups, suggesting more aggressive disease biology. On the other hand, in Huelva, a higher number of patients were diagnosed in stage IV and a lower percentage in stage I, which suggests that the difference in survival is due to late diagnosis. In fact, survival in Huelva is superior to Granada in all stages except stage IV, which reinforces this hypothesis. Also, in Huelva, there was a higher percentage of bilateral tumors, which have a worse prognosis and are more difficult to approach from the therapeutic point of view [28,29,30].

Women have a lower incidence of lung cancer than men as generally they smoke less than men [31]. However, the smoking prevalence in Spain has declined in men from 65% in 1978 to 31% in 2015, but it has increased from 17% in 1975 to 25% in 2015 [32]. This new pattern of tobacco consumption has important implications for the incidence and mortality of lung cancer by sex in Spain. For instance, the lung cancer sex-specific incidence rate ratio for men compared with women has decreased importantly from 9.6 times in the period 1993–1997 to 6.3 in 2003–2007 [33].

Overall we found higher lung cancer survival among women compared with men which is in line with research in other countries [34]. The mechanisms for these differences are not yet well understood but differences between the sexes such as health-seeking behavior have been postulated as a possible hypothesis to explain the differences [35,36,37,38]. For instance, a study in Spain found that women have worse perceptions of their health than men, making them attend health services more frequently than men [39].

We found remarkable differences related to the provision of cancer care in both southern regions that might explain cancer survival outcomes. All diagnostic tests except CT and MRI were applied differentially in the two regions. Thoracic imaging and bronchoscopy were more frequently used in Huelva, whereas PET, mediastinoscopy, and EBUS were more commonly used in Granada. Treatments that include surgery are more effective for the survival of lung cancer patients, although their use is only indicated in tumors in early stages. Besides, in a large number of patients, the only therapeutic option is with palliative intent, mainly because they are elderly patients with distant metastasis. That is why, to maximize the probability of survival, efforts for early detection of lung cancer must increase. We observed that the combination of treatments improves survival. Of all combinations, those that included surgery had the best results reducing death risk. The most effective treatment regarding survival was the combination of radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and surgery, reducing the risk of death by 94% compared to patients who did not receive treatment. Chemotherapy combined with surgery and surgery alone was also more effective than the other treatments. It is important to emphasize the relevance of early cancer detection for lung cancer surgery and survival. Nevertheless, surgery is only indicated in early stages. However, early lung cancer detection is still difficult [40]. In our study, surgery was only indicated in 15% of patients who were mostly in stage I (81%). Only 17 of the 1196 cases analyzed (1.4%) were included in a clinical trial at the time of the investigation.

A recent improvement of new therapies has had a slight influence in lung cancer survival—1-year survival rates have modestly increased, particularly among women who have a better prognosis and higher survival [41]. Unfortunately, the use of these new therapies, in particular, tyrosine kinase inhibitors [42, 43], has been scarce during the period of this study. It could be due to the slow introduction of some new treatments in our community. When analyzing the type of treatment, we observed that untreated patients have the highest percentages as they represent 40% and 32% in Granada and Huelva, respectively. Lung cancer patients, who were in poor condition and exhibited severe chronic complications or were in the late stages of the disease, usually receive only palliative treatment or no treatment at all.

To the extent of our knowledge, this is the first high-resolution study showing regional variability in patient, tumor, and healthcare determinants that also highlights a remarkably high prevalence of late diagnosis in Spain. However, more consistent comparative evidence is needed in terms of calendar time and sample size to externally validate the relevance of our findings.

In summary, the observed regional differences in lung cancer may be due to the late cancer diagnosis, which determines the use of less effective therapeutic options. Patient, tumor, and provision of healthcare determinants could partially explain the observed geographical variability. The results of our study justify the need for monitoring adherence to regional guidelines and promoting the harmonization of the best practice in lung cancer management and treatment.

Abbreviations

- ADC:

-

Adenocarcinoma

- CCI:

-

Charlson comorbidity index

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- EBUS:

-

Endobronchial ultrasound guided bronchoscopy

- EMR:

-

Excess mortality risks

- ICD-O-3:

-

International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition

- LCC:

-

Large cells carcinoma

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- SmCC:

-

Small cells carcinoma

- SqCC:

-

Squamous cells carcinoma

References

ECIS European Commission. https://ecis.jrc.ec.europa.eu/. Accessed 01 Mar 2018.

Galceran J, Ameijide A, Carulla M, Mateos A, Quirós JR, Rojas D, et al. Cancer incidence in Spain, 2015. Clin Transl Oncol. 2017;19:799–825.

Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108.

WHO. Globocan 2012—Home [Internet]. Globocan 2012. 2012. http://globocan.iarc.fr/Default.aspx. Accessed 1 Mar 2018.

Allemani C, Matsuda T, Di Carlo V, Harewood R, Matz M, Nikšić M, et al. Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000–14 (CONCORD-3): analysis of individual records for 37,513,025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries. Lancet. 2018;391:1023–75.

De Angelis R, Sant M, Coleman MP, Francisci S, Baili P, Pierannunzio D, et al. Cancer survival in Europe 1999–2007 by country and age: results of EUROCARE-5—a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:23–34.

Chirlaque MD, Salmerón D, Galceran J, Ameijide A, Mateos A, Torrella A, et al. Cancer survival in adult patients in Spain. Results from nine population-based cancer registries. Clin Transl Oncol. 2018;20(2):201–11.

Wong MCS, Lao XQ, Ho K-F, Goggins WB, Tse SLA. Incidence and mortality of lung cancer: global trends and association with socioeconomic status. Sci Rep. 2017;7:14300.

Tammemagi CM, Neslund-Dudas C, Simoff M, Kvale P. Smoking and lung cancer survival: the role of comorbidity and treatment. Chest. 2004;125:27–37.

Nordquist LT, Simon GR, Cantor A, Alberts WM, Bepler G. Improved survival in never-smokers vs current smokers with primary adenocarcinoma of the lung. Chest. 2004;126:347–51.

Tan YK, Wee TC, Koh WP, Wang YT, Eng P, Tan WC, et al. Survival among Chinese women with lung cancer in Singapore: a comparison by stage, histology and smoking status. Lung Cancer. 2003;40:237–46.

Fry WA, Phillips JL, Menck HR. Ten-year survey of lung cancer treatment and survival in hospitals in the United States: a national cancer data base report. Cancer. 1999;86:1867–76.

Alberts WM. Diagnosis and management of lung cancer executive summary: aCCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2007;132:1S–19S (2nd edition).

Xie L, Ugnat A-M, Morriss J, Semenciw R, Mao Y. Histology-related variation in the treatment and survival of patients with lung carcinoma in Canada. Lung Cancer. 2003;42:127–39.

Salmerón D, Chirlaque MD, Isabel Izarzugaza M, Sánchez MJ, Marcos-Gragera R, Ardanaz E, et al. Lung cancer prognosis in Spain: the role of histology, age and sex. Respir Med. 2012;106:1301–8.

Woods LM, Rachet B, Coleman MP. Origins of socio-economic inequalities in cancer survival: a review. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:5–19.

Viñas Casasola MJ, Fernández Navarro P, Fajardo Rivas ML, Gurucelain Raposo JL, Alguacil Ojeda J. Distribución municipal de la incidencia de los tumores más frecuentes en un área de elevada mortalidad por cáncer. Gac Sanit. 2017;31:100–7.

De Groot V, Beckerman H, Lankhorst GJ, Bouter LM. How to measure comorbidity: a critical review of available methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:221–9.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83.

Perme MP, Stare J, Esteve J. On estimation in relative survival. Biometrics. 2012;68:113–20.

Corazziari I, Quinn M, Capocaccia R. Standard cancer patient population for age standardising survival ratios. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:2307–16.

Dickman PW, Sloggett A, Hills M, Hakulinen T. Regression models for relative survival. Stat Med. 2004;23:51–64.

StataCorp. Stata statistical software: release 12. College Station: StataCorp LP; 2011.

Francisci S, Minicozzi P, Pierannunzio D, Ardanaz E, Eberle A, Grimsrud TK, et al. Survival patterns in lung and pleural cancer in Europe 1999-2007: results from the EUROCARE-5 study. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:2242–53.

Aggarwal C, Langer CJ. Older age, poor performance status and major comorbidities: how to treat high-risk patients with advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:130–6.

Lembicz M, Gabryel P, Brajer-Luftmann B, Dyszkiewicz W, Batura-Gabryel H. Comorbidities with non-small cell lung cancer: is there an interdisciplinary consensus needed to qualify patients for surgical treatment? Ann Thorac Med. 2018;13:101–7.

Sacher AG, Dahlberg SE, Heng J, Mach S, Jänne PA, Oxnard GR. Lung cancer diagnosed in the young is associated with enrichment for targetable genomic alterations and poor prognosis HHS Public Access. JAMA Oncol. 2016;1:313–20.

De Leyn P, Moons J, Vansteenkiste J, Verbeken E, Van Raemdonck D, Nafteux P, et al. Survival after resection of synchronous bilateral lung cancer. Eur J Cardio Thorac Surg. 2008;34:1215–22.

Tsunezuka Y, Matsumoto I, Tamura M, Oda M, Ohta Y, Shimizu J, et al. The results of therapy for bilateral multiple primary lung cancers: 30 years experience in a single centre. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30:781–5.

Mun M, Kohno T. Single-stage surgical treatment of synchronous bilateral multiple lung cancers. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:1146–51.

Gandini S, Botteri E, Iodice S, Boniol M, Lowenfels ABB, Maisonneuve P, et al. Tobacco smoking and cancer: a meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:155–64.

Sánchez-Cruz JJ, García LI, Mayoral JM. Encuesta andaluza de salud 2015–2016 de Adultos. Sevilla: Consejería de Salud. Junta de Andalucía; 2016.

Galceran J, Amejeide A, Carulla M, Mateps A, Quirós JR, Alemán A, et al. Estimaciones de la incidencia y la supervivencia del cáncer en españa y su situación en europa. Red Española de Registros de Cáncer. 2014;1–58.

Fu JB, Kau TY, Severson RK, Kalemkerian GP. Lung cancer in women: analysis of the national surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. Chest. 2005;127:768–77.

Moore R, Doherty D, Chamberlain R, Khuri F. Sex differences in survival in non-small cell lung cancer patients 1974-1998. Acta Oncol. 2004;43:57–64.

Wisnivesky JP, Halm EA. Sex differences in lung cancer survival: do tumors behave differently in elderly women? J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1705–12.

Micheli A, Ciampichini R, Oberaigner W, Ciccolallo L, de Vries E, Izarzugaza I, et al. The advantage of women in cancer survival: an analysis of EUROCARE-4 data. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:1017–27.

Skuladottir H, Olsen JH. Can reproductive pattern explain better survival of women with lung cancer? Acta Oncol. 2006;45:47–53.

Redondo-Sendino A, Guallar-Castillón P, Banegas JR, Rodríguez-Artalejo F. Gender differences in the utilization of health-care services among the older adult population of Spain. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:155.

Salomaa E-R, Sallinen S, Hiekkanen H, Liippo K. Delays in the diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer. Chest. 2005;128:2282–8.

Sant M, Allemani C, Santaquilani M, Knijn A, Marchesi F, Capocaccia R. EUROCARE-4. Survival of cancer patients diagnosed in 1995–1999. Results and commentary. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:931–91.

Shroff GS, de Groot PM, Papadimitrakopoulou VA, Truong MT, Carter BW. Targeted Therapy and Immunotherapy in the Treatment of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Radiol Clin North Am. 2018;56:485–95.

Nishinarita N, Igawa S, Kasajima M, Kusuhara S, Harada S, Okuma Y, et al. Smoking History as a predictor of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients with non-small cell lung cancer harboring EGFR mutations. Oncology. 2018;95(2):109–15.

Acknowledgements

Maria Jose Sanchez Perez is supported by the Andalusian Department of Health: Research, Development, and Innovation Office project grant PI-0152/2017. Miguel Angel Luque-Fernandez is supported by the Spanish National Institute of Health, Carlos III Miguel Servet I Investigator Award (CP17/00206).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Ethical approval

This study involves a secondary data analysis from existing data and records. The information was recorded by the investigator in such a manner that subjects could not be identified, directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects. The regional ethical review board approved the study proposal. Furthermore, data from the participant cancer registry has data management policies in place allowing for the preservation of individual patients’ confidentiality including the ethical approvals from local mandatory bodies.

Informed consent

For this type of study formal consent is not required

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Rodríguez-Barranco, M., Salamanca-Fernández, E., Fajardo, M.L. et al. Patient, tumor, and healthcare factors associated with regional variability in lung cancer survival: a Spanish high-resolution population-based study. Clin Transl Oncol 21, 621–629 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-018-1962-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-018-1962-9