Abstract

The Covid-19 stay-at-home restrictions put in place in New York City were followed by an abrupt shift in movement away from public spaces and into the home. This study used interrupted time series analysis to estimate the impact of these changes by crime type and location (public space vs. residential setting), while adjusting for underlying trends, seasonality, temperature, population, and possible confounding from the subsequent protests against police brutality in response to the police-involved the killing of George Floyd. Consistent with routine activity theory, we found that the SAH restrictions were associated with decreases in residential burglary, felony assault, grand larceny, rape, and robbery; increases in non-residential burglary and residential grand larceny motor vehicle; and no change in murder and shooting incidents. We also found that the protests were associated with increases in several crime types: felony assault, grand larceny, robbery, and shooting incidents. Future research on Covid-19’s impact on crime will need to account for these potentially confounding events.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

To control the transmission of Covid-19, New York City implemented a variety of stay-at-home (SAH) restrictions, closing non-essential businesses, schools, restaurants, and theaters, and barring all non-essential public gatherings (New York State Department of Health, 2020). Routine activity theory (RAT) argues that such changes in day-to-day routines can impact the distribution of crime in a community. The theory posits that predatory crimes against persons or property require three elements—(1) a motivated offender, (2) presence of a suitable target, and (3) the absence of a capable guardian—and that changes in routines related to work, school, and leisure can affect whether these elements come together to create opportunities for crime (Clarke & Felson, 2017; Cohen & Felson, 1979; Felson, 2013). For example, after World War II when people’s routines shifted away from the family household and into the labor force and single-family homes, new opportunities for offenders to interact with unguarded targets fueled an increase in crime during the 1950s and 1960s (Cohen & Felson, 1979).

With people shifting more activities into the home during the pandemic, RAT predicts changes in the distribution of crime opportunities depending on the type of crime and location. Specifically, in public settings it predicts fewer opportunities for crime against people (e.g., assault, larceny, robbery) and more opportunities for crime against unguarded property (e.g., car theft, non-residential burglary), while in residential settings it predicts fewer opportunities for crime against property (eg., residential burglary) and more opportunities for crime between members of a residence (e.g., domestic violence). From a RAT perspective, broad changes in the level of various crime types in a community would therefore be expected to coincide with the onset of the SAH restrictions.

Findings from research on the impact of SAH restrictions have generally been consistent with RAT. Typically, researchers have examined the effect of these changes using either interrupted time series analysis, step-ahead ARIMA forecasts, difference-in-differences, or event studies. Table 1 summarizes the findings from studies to date on the impact of SAH restrictions globally. Following the implementation of SAH restrictions, decreases were found in assault (De la Miyar et al., 2021a, b; Borrion et al., 2020; Gerell et al., 2020; Halford et al., 2020); robbery (Estévez-Soto, 2021; Poblete-Cazenave, 2020), theft (De la Miyar et al., 2021a, b; Halford et al., 2020; Hodgkinson & Andresen, 2020; Payne et al., 2020; Poblete-Cazenave, 2020), theft from vehicle (Halford et al., 2020; Hodgkinson & Andresen, 2020), residential burglary (Abrams 2021; Ashby, 2020a, b; Carter & Turner, 2021; Gerell et al., 2020; Halford et al., 2020; Mohler et al., 2020) and drug crime (Abrams, 2021), while increases were found in non-residential burglary (Abrams, 2021; Carter & Turner, 2021; Felson et al., 2020; Hodgkinson & Andresen, 2020; Payne et al., 2020), car theft (Abrams, 2021; Mohler et al., 2020) domestic violence (Bullinger et al. 2021; Leslie & Wilson, 2020; Mohler et al., 2020; Piquero et al., 2020), cybercrime (Buil-Gil et al., 2020), drug trafficking (Rashid, 2021), and shooting incidents (Kim & Phillips, 2021).

While a general pattern emerged, important differences were seen across locations, crime types, and time periods. Several studies have attempted to identify the factors that might explain the disparate effects. Nivette et al. (2021) found that locations that imposed more stringent restrictions over movement in public spaces saw larger declines in crime. Brantingham et al. (2021) found that gang-related criminal activities were largely unaffected by the SAH restrictions. Campedelli et al. (2020) found that differences across subcommunities within the same city were associated with a variety of factors, including prior level of crime in a sub-community, perceptions of safety, vacant housing rate, income heterogeneity, poverty, and demographics. Felson et al. (2020) distinguished residential areas from mixed commercial/residential areas and found an increase in burglary only in mixed land use areas. Finally, De la Miyar et al. (2021b) found that the trajectory for less severe crimes (assault, battery, fraud, property crime, theft) followed a U-shaped pattern, falling to a low point about two months after the SAH restrictions and several months later returning back to nearly pre-pandemic levels.

There are several remaining gaps in the research on the impact of the SAH restrictions. First, much of the early research has been limited to the first several months of the pandemic, with several studies having somewhat longer study periods. As SAH restrictions remained in effect beyond this time in many places, studies with longer time periods are needed. Second, studies in the U.S. that extend beyond May 2020 are potentially confounded by the nationwide protests in response to the police-involved killing of George Floyd (Kim & Phillips, 2021; Rosenfeld et al., 2021). In recent years, several such events were followed by an abrupt increase in some crime types, often referred to as the “Ferguson effect,” including robberies (Pyrooz et al., 2016), shootings (Arthur & Asher, 2016; Morgan & Pally, 2016) and murders (Arthur & Asher, 2016; Morgan & Pally, 2016). Research suggests that these increases might be due to a pullback in policing (Devi & Fryer, 2020; Shi, 2009) or the erosion of community trust (Capellan et al., 2020; Rosenfeld, 2016). With longer time series data, it is therefore important to control for the possible history bias caused by these alternative events (Shadish et al., 2002). Third, as Stickle and Felson (2020) have pointed out, when researching crime in a pandemic it is critical to account for place-based differences between residential and non-residential settings. While several studies have accounted for these differences for burglary (Abrams, 2021; Ashby, 2020b; Carter & Turner, 2021; Felson et al., 2020; Gerell et al., 2020; Halford et al., 2020; Hodgkinson & Andresen, 2020; Mohler et al., 2020; Payne et al., 2020) and assault (Gerell et al., 2020), this level of granularity is so far lacking for other crime types.

Current Focus

On March 16, 2020, New York City initiated a series of stay-at-home restrictions to curb the spread of Covid-19. Research on the impact of similar restrictions has shown sharp and immediate changes in the levels of various crime types, broadly consistent with RAT. However, a rigorous analysis of the impact of the restrictions imposed in New York City, the location of one of the U.S.’s most lethal outbreaks (Yang et al., 2021) and strictest lockdowns (Hale et al., 2020), has yet to be conducted. Also, prior research on the impact of similar SAH restrictions has had several limitations, including: (1) short study periods, (2) lack of place-based distinctions for various crime types, and (3) in the U.S. a failure to control for the subsequent protests against police brutality. To address these limitations, this study will estimate the impact of New York City’s SAH restrictions on multiple crime types using interrupted time series models. The models will be stratified by incident location to explore place-based differences (public space v. residential) and will include a second breakpoint to account for the subsequent period of protests, allowing us to explore differences in the impact of the SAH restrictions in New York City by crime type, location, and time period.

Data and Methods

Crime Data

Crime incident data were collected from the New York Police Department’s (NYPD) open portal (NYPD, 2021).Footnote 1 Crime types were classified by the NYPD based on New York State Penal Law (except for rape, which follows the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting definition). In all, eight crime types were included in the analysis:

-

burglary

-

felony assault

-

grand larceny

-

grand larceny motor vehicle

-

murder

-

rape

-

robbery

-

shooting incidents

For the period of January 1, 2017, to December 31, 2020, crime incidents were aggregated by day for each crime type. Data on incident location (NYPD’s “description of premises” variable) was used to identify whether an incident was carried out in a public space or a residential setting. This was possible for all crime types except murder and shootings, for which the NYPD does not provide premises type information.

SAH Restrictions

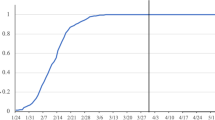

The first SAH restrictions in New York City occurred on March 16, 2020, closing schools, restaurants (except takeout), bars, theaters, and gyms, and limiting public gatherings (Axelson, 2020). According to mobility data from this time, these restrictions caused a dramatic shift in people’s routines away from public spaces and into the home (Fig. 1). To measure the impact of these restrictions on crime incidents, we used a dummy variable whereby 0 represents the pre-intervention period (January 1, 2017 – March 15, 2020) and 1 represents the intervention period (March 16, 2020 – December 31, 2020).

Google mobility data on time spent at home (February 15, 2020 – December 31, 2020) (Google, 2021). Solid red line indicates the start of the SAH restrictions (March 16, 2020) and the dashed red line indicates the start of the protests against police brutality (May 28, 2020). The measure is calculated based on location history data from Google accounts. Google maps are used to distinguish places of residences from other location types. Beginning on February 15, 2020, the data captures changes in duration at a place of residence compared to a pre-COVID-19 baseline period (the median value from the 5-week period Jan 3 – Feb 6, 2020). Data were aggregated across the five New York City counties. Note that the largest possible change in mobility may only be around 50%, as people already spend much of their time at home

Protests against Police Brutality

The police-involved killing of George Floyd sparked sustained nationwide protests against police brutality, which in New York City began on May 28, 2020 (NYC Department of Investigation, 2020). According to data from the Armed Conflict and Location Event Data (ACLED) project, the social unrest continued until early December, and included a total of 179 Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests against police brutality across New York City (ACLED, 2021).

There are several reasons to expect that events were associated with changes in crime. Prior research has found that similar protests in the past were followed by an increase in multiple crime types (Arthur & Asher, 2016; Morgan & Pally, 2016; Pyrooz et al., 2016). A study of 34 U.S. cities, conducted by the National Commission on Covid-19 and Criminal Justice (NCCCJ), found an association between the start of the protests against police brutality in 2020 and increases in homicide, aggravated assault, and motor vehicle theft (Rosenfeld et al., 2021). That other countries with similar responses to Covid-19 did not see a rise in crime suggests an alternative explanation for such increases in the U.S. (Economist, 2021). Finally, in the aftermath of the protests there was a sharp and sustained pullback in policing for the remainder of 2020, as measured by the frequency of Terry stops (Fig. 2) and arrests (Fig. 3). Thus, to control for the impact of these events, we included a second dummy variable whereby 0 represents the period before the social unrest (January 1, 2017 – May 27, 2020) and 1 represents the period after (May 28, 2020 – December 31, 2020).

Descriptive Analysis

We conducted descriptive analyses for each crime type. The mean and standard deviation of daily counts are presented for each segment of the analysis: the pre-SAH period (January 1, 2017 – March 15, 2020), the post-SAH period (March 16, 2020 – May 27, 2020), and the post-protest period (May 28, 2020 – December 31, 2020). For crimes types with location information available (burglary, felony assault, grand larceny, grand larceny motor vehicle, rape, robbery), the descriptive analysis was stratified by location: public space vs. residential.

Interrupted Time Series Analysis

We used interrupted time series (ITS) analysis to estimate the impact of the SAH restrictions on each crime type. In the absence of a randomized-controlled experiment, ITS is considered a strong quasi-experimental alternative (Shadish et al., 2002). Following Nivette et al. (2021), the ITS models were estimated using segmented Poisson generalized linear models with a logit-link function, given the count nature and daily frequency of the crime incident data. Because RAT predicts immediate changes—depending on whether motivated offenders and targets converge at a particular time—we estimated the impact of the SAH restriction on the change in level of multiple crime types (Bernal et al., 2017). For nearly all crime types (burglary, felony assault, grand larceny, grand larceny motor vehicle, rape, robbery), the NYPD provides a description of the location type for each crime incident. Where this information was available, the models were stratified by location.

To control for possible confounding due to cyclical crime trends, such as day-of-the week crime patterns and seasonal crime patterns (Andresen & Malleson, 2015; McDowall et al., 2012), dummy variables were included for day-of-the-week, month, and year. Additionally, average daily temperature (°F) was included to adjust for its association with property and violent crime, which has been found to be independent of seasonal fluctuations (Field, 1992; McDowall et al., 2012), Historical weather data was manually retrieved from Weather Underground (Weather Underground, 2021). Based on an inspection of the data, dummy variables were also included for outliers for a particular crime type on a given day (e.g., January 1st).

We took several further steps to ensure the models were appropriately specified. Augmented Dickey-Fuller tests were run to test for a unit-root process (random walk with or without drift) in the time series. For each crime time series, we were able to reject the null that it was generated by a non-stationary process (Table 2).

All models included a population offset based on New York City population estimates for a given year. Population data came from the U.S. Census Bureau (Census, 2021). To address overdispersion, a scaling adjustment was used to produce more conservative estimates of uncertainty (Bernal et al., 2017; Bhaskaran et al., 2013). Finally, to correct for autocorrelation, we examined the ACF and PACF model residual plots, and where indicated included autoregressive term(s) (AR) for lagged values and/or moving average (MA) term(s) for lagged residuals. Akaike information criterion values were used to assess model fit.

Results

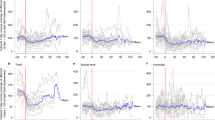

We used ITS analysis to estimate the impact of SAH restrictions on multiple crime types in New York City. To account for possible confounding due to the subsequent protests, our models were segmented by two breakpoints to create three periods: the pre-SAH period, the post-SAH period, and the post-protest period. Figure 4 shows the trends for each crime type over the course of these three time periods.

Descriptive statistics across these three time periods are presented for each crime category in Table 3. During the period of the SAH restrictions, the daily average number of incidents decreased for grand larceny (-58.4), robbery (-12.3), felony assault (-11.7), and rape (-2.1), and increased for burglary (+ 5.4), grand larceny motor vehicle (+ 4.0) shooting incidents (+ 0.1), and murder (+ 0.2). Compared to the post-SAH period, in the post-protest period the daily average number of incidents increased for all crime categories: grand larceny (+ 32.2), felony assault (+ 15.1), robbery (+ 13.0), grand larceny motor vehicle (+ 9.5), burglary (+ 8.3), shooting incidents (+ 3.6), rape (+ 0.5), murder (+ 0.5).

Segmented Poisson regression was used to estimate the change in level of multiple crime types following the SAH restrictions, while controlling for underlying trends, seasonality, temperature, population, and possible confounding from the protests against police brutality. Findings from the ITS analyses are presented in Table 4. After the implementation of the SAH restrictions, we found several statistically significant level changes: rape decreased by 40% (IRR = 0.60; 95% CI, 0.45–0.81; p < 0.01), grand larceny decreased by 33% (IRR = 0.67; 95% CI, 0.63–0.72; p < 0.001), robbery decreased by 32% (IRR = 0.68; 95% CI, 0.63–0.74; p < 0.001), and felony assault decreased by 21% (IRR = 0.79; 95% CI, 0.74–0.85; p < 0.001). While not the focus of this study, it is notable that there were also several statistically significant level changes following the protests: shootings increased by 96% (IRR = 1.96; 95% CI, 1.59–2.41; p < 0.001), robbery increase by 24% (IRR = 1.24; 95% CI, 1.15–1.32; p < . 001), felony assault increased by 23% (IRR = 1.23, 95% CI, 1.17–1.31; p < 0.001), and grand larceny increased by 22% (IRR = 1.22; 95% CI, 1.16–1.29; p < 0.001).

Stratified by Incident Location

To examine whether there were place-based differences in the impact of the SAH restrictions, our analyses were stratified by location: public space vs. residential setting. Descriptive statistics across the three relevant time periods are presented in Table 5. In public spaces, during the post-SAH period, the daily average number of incidents decreased for grand larceny (-42.6), robbery (-11.0), felony assault (-8.9), and rape (-0.5), but increased for burglary (+ 9.0) and grand larceny motor vehicle (+ 3.1). In residential settings, during the post-SAH period, the daily average number of incidents decreased for grand larceny (-15.0), burglary (-3.5), felony assault (-1.7), rape (-1.6), and robbery (-1.2), but increased for grand larceny motor vehicle (+ 0.9).

Results from the stratified ITS analyses are presented in Tables 6 and 7. In public spaces, there were several statistically significant level changes: rape decreased by 46% (IRR = 0.54; 95% CI, 0.33–0.88; p < 0.05), robbery decreased by 37% (IRR = 0.63; 95% CI, 0.58–0.69; p < 0.001), grand larceny decreased by 37% (IRR = 0.63; 95% CI, 0.59–0.68; p < 0.001), felony assault decreased by 34% (IRR = 0.66; 95% CI, 0.59–0.73; p < 0.001), and burglary increased by 28% (IRR = 1.28; 95% CI, 1.15–1.42; p < 0.001). In residential settings, there were also several statistically significant level changes: rape decreased by 30% (IRR = 0.70; 95% CI, 0.49–0.99; p < 0.05), grand larceny decreased by 24% (IRR = 0.76; 95% CI, 0.68–0.84; p < 0.001), burglary decreased by 14% (IRR = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.78–0.95; p < 0.05), felony assault decreased by 10% (IRR = 0.90; 95% CI, 0.83–0.98; p < 0.05), and grand larceny motor vehicle increased by 67% (IRR = 1.67; 95% CI, 1.22–2.28; p < 0.01).

Discussion

To curtail the spread of Covid-19, New York City imposed one of the most stringent lockdowns in the U.S. (Hale et al., 2020). The ensuing shift in day-to-day routines created one instance of what Stickle and Felson (2020) describe as the largest criminological experiment in history. Relying on routine activity theory, we predicted that the SAH restrictions would impact the level of crime depending on the crime type and location. Prior research has shown dramatic changes in the distribution of crime following the implementation of SAH restriction in locations across the globe. However, to date no rigorous study has been conducted on the impact of SAH restrictions in New York City. Moreover, earlier research has had several important limitations, including short study periods, lack of place-based distinctions for various crime types, and in the U.S. a lack of control for possible confounding from the subsequent protests against police brutality. To address these limitations, we used ITS analysis to estimate the impact of the SAH restriction on multiple crime types in New York City, while adjusting for underlying trends, seasonality, temperature, population, and possible confounding from the subsequent protests. The analyses were then stratified by incident location.

There was considerable variation in the impact of the SAH restrictions by crime type and location. For burglary, there was no change in the aggregate, but broken down by location there was a 26% increase in public spaces and a 14% decrease in residential settings. For felony assault, there was a 21% decrease in the aggregate, and broken down by location a 34% decrease in public spaces and a 10% decrease in residential settings. For grand larceny, there was a 33% decrease in the aggregate, and broken down by location a 37% decrease in public spaces and a 24% decrease in residential settings. For grand larceny motor vehicle, there was no change in the aggregate, and broken down by location a 67% increase in residential settings only. For murder, there was no change (data was not available for stratified analysis). For rape, there was a 40% decrease in the aggregate, and broken down by location a 46% decrease in public spaces and a 30% decrease in residential settings. For robbery, there was a 32% reduction in the aggregate, and broken down by location a 37% decrease in public spaces only. For shooting incidents, there was no change (data was not available for stratified analysis).

There were also several notable increases in the level of crime in the period following the protests against police brutality: shootings (96%), robbery (24%), felony assault (23%), grand larceny (22%), and grand larceny motor vehicle (8%). It is possible that some of these changes represent a regression back to pre-pandemic levels due to rising mobility, as was seen in Mexico City’s U-shaped crime recovery (De la Miyar et al., 2021b). However, this is a less plausible when it comes to the increase in shooting incidents, which were unaffected by the SAH restrictions and then rose sharply following the protests. One possibility is that both of these events had an independent effect on crime, as Kim & Phillips (2021) found for certain kinds of shooting incidents. More research is needed to tease apart the impact of these two events, as well as to examine other factors that may have played a role (e.g., the increased sale of firearms in 2020; Economist, 2021).

Overall, our findings contribute to the literature on the effect of SAH restrictions and crime in several ways. First, our findings suggest that SAH restrictions impacted crime by shifting the distribution of suitable targets. With fewer people to target on city streets, we found decreases in predatory crimes commonly committed against individuals in public places: felony assault, grand larceny, rape, and robbery. Importantly, these effects were found either exclusively in public spaces, as was the case with robbery, or to have a much greater magnitude in public spaces compared to residential settings, as was the case with felony assault, grand larceny, and rape. Second, our findings suggest that SAH restrictions impacted crime by displacing capable guardianship. With fewer potential guardians in the streets but more in residences, we found a divergent impact on burglary: an increase in public spaces but a decrease in residential settings. Third, this was the first study to find an increase in grand larceny motor vehicle incidents exclusively in residential settings, despite the increased presence of capable guardians in and around homes. We suspect that this was simply because there were a greater number of cars parked in residential settings after the lockdown, or as Willie Sutton would have put it, “that’s where the cars were.” Fourth, we found that SAH restrictions had no impact on either murder or shooting incidents. This was likely due to the fact that such crimes are often connected with gang-related activity (National Gang Center, 2020), which remained stable throughout the pandemic (Brantingham et al., 2021; Rashid, 2021). Finally, the findings lend credence to our concern about confounding from the protests against police brutality, as these events were followed by immediate changes in the level of multiple crime types.

Limitations

Several limitations of this paper are worth noting. First, we used reported incidents as our measure of crime. Thus, one concern is whether the crime declines we saw reflect a true change or an artifact of hesitancy to report (For a lengthy discussion of why the changes are unlikely to be an artifact of hesitancy to report, see Abrams, 2021). Second, changes in key elements of routine activity theory were not directly measured, but instead were presumed given the dramatic increase in time spent at home following the SAH order. Third, several crime types that might have been affected by changes in routine activity were not included in this study, such as cybercrime, drug crime, domestic violence, and subway crime. Future studies are needed to evaluate the impact of SAH restrictions on these crime types in New York City. Fourth, while we found that the protests against police brutality were temporally associated with increases in several crime types, it is possible that the circumstances created by the SAH restrictions also played a causal role. More research is needed to disentangle the impact of these two causes. Fifth, though New York City provided a unique opportunity to study the effect of stringent SAH restrictions during a very lethal outbreak, it is unclear how generalizable the findings are to other locations. Future research is needed to identify factors responsible for any variation found in the impact of SAH restrictions across geographic locations. Finally, though routine activity theory proved useful as a framework, we have no doubt that other theories can be used to better understand Covid-19’s impact on crime.

Conclusions

The broad stay-at-home restrictions imposed in New York City were followed by an abrupt shift in movement. Consistent with routine activity theory, we found that these changes were associated with decreases in residential burglary, felony assault, grand larceny, rape, robbery; increases in non-residential burglary and residential grand larceny motor vehicle; and no change in murder and shooting incidents. Several months after the start of the SAH restrictions, New York City experienced sustained and mass protests against police brutality followed by a sharp drop in the frequency of Terry stops and arrests. We found that these events were associated with increases in several crime types: felony assault, grand larceny, robbery, and shooting incidents. Future research on Covid-19’s impact on crime will need to account for these potential confounding events.

Data Availability

Datasets used in the analysis can be made available.

Code Availability

Code used in the analysis (Stata do files) can be made available.

Notes

Data on burglary, felony assault, grand larceny, grand larceny motor vehicle, rape, and robbery were collected from the NYPD’s Incident-level Complaint database. Data on shootings were collected from the NYPD’s Incident-level Shooting database. For shootings with multiple victims, the data were de-duplicated to identify unique shooting incidents. Data on homicides were collected from the NYPD’s Supplemental Annual Homicide report.

References

Abrams, D. S. (2021). COVID and crime: An early empirical look. Journal of Public Economics, 194, 104344.

Andresen, M. A., & Malleson, N. (2015). Intra-week spatial-temporal patterns of crime. Crime Science, 4(1), 1–11.

Armed Conflict and Location Data (2021): Retrieved from: https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool/

Arthur, R., & Asher, J. (2016). Gun violence spiked—and arrests declined—in Chicago right after the Laquan McDonald video release. FiveThirtyEight. Retrieved from: https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/gun-violence-spiked-and-arrests-declined-in-chicago-right-after-the-laquan-mcdonald-video-release

Ashby, M. P. (2020). Changes in police calls for service during the early months of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 14(4), 1054–1072.

Ashby, M. P. (2020b). Initial evidence on the relationship between the coronavirus pandemic and crime in the United States. Crime Science, 9, 1–16.

Axelson, B. (2020). Coronavirus timeline in NY: Here’s how Gov. Cuomo has responded to COVID-19 pandemic since January. Syracuse. https://www.syracuse.com/coronavirus/2020/04/coronavirus-timeline-in-ny-heres-how-gov-cuomo-has-responded-to-covid-19-pandemic-since-january.html

Bernal, J. L., Cummins, S., & Gasparrini, A. (2017). Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: A tutorial. International Journal of Epidemiology, 46(1), 348–355.

Bhaskaran, K., Gasparrini, A., Hajat, S., Smeeth, L., & Armstrong, B. (2013). Time series regression studies in environmental epidemiology. International Journal of Epidemiology, 42(4), 1187–1195.

Borrion, H., Kurland, J., Tilley, N., & Chen, P. (2020). Measuring the resilience of criminogenic ecosystems to global disruption: A case-study of COVID-19 in China. Plos one, 15(10), e0240077.

Brantingham, J. P., Tita, G. E., & Mohler, G. (2021). Gang‐related crime in Los Angeles remained stable following COVID‐19 social distancing orders. Criminology & Public Policy, 20(3), 423–436.

Buil-Gil, D., Miró-Llinares, F., Moneva, A., Kemp, S., & Díaz-Castaño, N. (2020). Cybercrime and shifts in opportunities during COVID-19: A preliminary analysis in the UK. European Societies, 23(sup1), S47–S59.

Bullinger, L. R., Carr, J. B., & Packham, A. (2021). COVID-19 and crime: Effects of stay-at-home orders on domestic violence. American Journal of Health Economics, 7(3), 000–000.

Calderon-Anyosa, R. J., & Kaufman, J. S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 lockdown policy on homicide, suicide, and motor vehicle deaths in Peru. Preventive Medicine, 143, 106331.

Campedelli, G. M., Favarin, S., Aziani, A., & Piquero, A. R. (2020). Disentangling community-level changes in crime trends during the COVID-19 pandemic in Chicago. Crime Science, 9(1), 1–18.

Capellan, J. A., Lautenschlager, R., & Silva, J. R. (2020). Deconstructing the Ferguson effect: A multilevel mediation analysis of public scrutiny, de-policing, and crime. Journal of Crime and Justice, 43(2), 125–144.

Carter, T. M., & Turner, N. D. (2021). Examining the immediate effects of COVID-19 on residential and commercial burglaries in Michigan: An interrupted time-series analysis. Journal of Criminal Justice, 76, 101834.

Clarke, R. V., & Felson, M. (2017). Introduction: Criminology, routine activity, and rational choice (1st ed.). In Routine activity and rational choice (pp. 1–14). Routledge

Cohen, L. E., & Felson, M. (1979). Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review, 44, 588–608.

Census (2021). United States Census Bureau Quick Facts. Retrieved from: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts

De la Miyar, J. R. B., Hoehn-Velasco, L., & Silverio-Murillo, A. (2021). Druglords don’t stay at home: COVID-19 pandemic and crime patterns in Mexico City. Journal of Criminal Justice, 72, 101745.

De la Miyar, J. R. B., Hoehn-Velasco, L., & Silverio-Murillo, A. (2021b). The U-shaped crime recovery during COVID-19: Evidence from national crime rates in Mexico. Crime Science, 10(1), 1–23.

Devi, T., & Fryer Jr, R. G. (2020). Policing the Police: The Impact of "Pattern-or-Practice" Investigations on Crime (No. w27324). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Economist (2021, March 27). In 2020 American Experienced a Terrible Surge in Murder. Why? Retrieved from: https://www.economist.com/united-states/2021/03/25/in-2020-america-experienced-a-terrible-surge-in-murder-why

Estévez-Soto, P. R. (2021). Crime and COVID-19: Effect of changes in routine activities in Mexico City. Crime Science, 10(1), 1–17.

Felson, M. (2013). Routine activity approach. In Environmental criminology and crime analysis (pp. 92–99). Willan.

Felson, M., Jiang, S., & Xu, Y. (2020). Routine activity effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on burglary in Detroit, March 2020. Crime Science, 9(1), 1–7.

Field, S. (1992). The effect of temperature on crime. The British Journal of Criminology, 32(3), 340–351.

Garnett, Margaret (2020). Investigation into NYPD Response to the George Floyd Protests. New York City Department of Investigation.

Gerell, M., Kardell, J., & Kindgren, J. (2020). Minor covid-19 association with crime in Sweden. Crime Science, 9(1), 1–9.

Google (2021). COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports. Retrieved from https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility/

Hale, T., Atav, T., Hallas, L., Kira, B., Phillips, T., Petherick, A., & Pott, A. (2020). Variation in US states responses to COVID-19. Blavatnik School of Government.

Halford, E., Dixon, A., Farrell, G., Malleson, N., & Tilley, N. (2020). Crime and coronavirus: Social distancing, lockdown, and the mobility elasticity of crime. Crime Science, 9(1), 1–12.

Hawdon, J., Parti, K., & Dearden, T. E. (2020). Cybercrime in America amid covid-19: The initial results from a natural experiment. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 546–562.

Hodgkinson, T., & Andresen, M. A. (2020). Show me a man or a woman alone and I’ll show you a saint: changes in the frequency of criminal incidents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Criminal Justice, 69, 101706.

Kim, D. Y., & Phillips, S. W. (2021). When COVID-19 and guns meet: A rise in shootings. Journal of Criminal Justice, 73, 101783.

Leslie, E., & Wilson, R. (2020). Sheltering in place and domestic violence: Evidence from calls for service during COVID-19. Journal of Public Economics, 189, 104241.

McDowall, D., Loftin, C., & Pate, M. (2012). Seasonal cycles in crime, and their variability. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 28(3), 389–410.

Mohler, G., Bertozzi, A. L., Carter, J., Short, M. B., Sledge, D., Tita, G. E., … & Brantingham, P. J. (2020). Impact of social distancing during COVID-19 pandemic on crime in Los Angeles and Indianapolis. Journal of Criminal Justice, 68, 101692.

Moise, I. K., & Piquero, A. R. (2021). Geographic disparities in violent crime during the COVID-19 lockdown in Miami-Dade County, Florida, 2018–2020. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 17, 1–10.

Morgan, S. L., and Pally, J. A. 2016. Ferguson, Gray, and Davis: An analysis of recorded crime incidents and arrests in Baltimore City, March 2010 through December 2015. Obtained from http://socweb.soc.jhu.edu/faculty/morgan/papers/MorganPally2016.pdf

National Gang Center (2020). National Youth Gang Survey Analysis. 2020. https://www.nationalgangcenter.gov/survey-analysis/measuring-the-extent-of-gang-problems.

New York Police Department (2021). Retrieved from: https://www1.nyc.gov/site/nypd/stats/crime-statistics/citywide-crime-stats.page

New York State Department of Health (2020). Retrieved from: http://coronavirus.health.ny.gov/new-york-state-pause

Nivette, A. E., Zahnow, R., Aguilar, R., Ahven, A., Amram, S., Ariel, B., … & Eisner, M. P. (2021). A global analysis of the impact of COVID-19 stay-at-home restrictions on crime. Nature Human Behaviour, 1–10.

Payne, J. L., Morgan, A., & Piquero, A. R. (2020). COVID-19 and social distancing measures in Queensland, Australia, are associated with short-term decreases in recorded violent crime. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 1–25.

Piquero, A. R., Riddell, J. R., Bishopp, S. A., Narvey, C., Reid, J. A., & Piquero, N. L. (2020). Staying home, staying safe? A short-term analysis of COVID-19 on Dallas domestic violence. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 601–635.

Poblete-Cazenave, R. (2020). The great lockdown and criminal activity-evidence from Bihar, India. India (June 8, 2020).

Pyrooz, D. C., Decker, S. H., Wolfe, S. E., & Shjarback, J. A. (2016). Was there a Ferguson Effect on crime rates in large US cities? Journal of Criminal Justice, 46, 1–8.

Rashid, S. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on selected criminal activities in Dhaka Bangladesh. Asian Journal of Criminology, 16(1), 5–17.

Rosenfeld, R. (2016). Documenting and explaining the 2015 homicide rise: Research directions. Washington, DC.

Rosenfeld, R. Abt, T., Lopez, E. (2021). Pandemic, Social Unrest, and Crime in U.S. Cities: 2020 Year-End Update. Washington, D.C.: Council on Criminal Justice.

Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference/William R. Shadish, Thomas D. Cook, Donald T. Campbell. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Shen, Y., Fu, R., & Noguchi, H. (2021). COVID‐19's Lockdown and Crime Victimization: The State of Emergency under the Abe Administration. Asian Economic Policy Review.

Shi, L. (2009). The limit of oversight in policing: Evidence from the 2001 Cincinnati riot. Journal of Public Economics, 93(1–2), 99–113.

Stickle, B., & Felson, M. (2020). Crime rates in a pandemic: The largest criminological experiment in history. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 525–536.

Weather Underground (2021). Historical Weather. Retrieved from: www.wunderground.com/history

Yang, W., Kandula, S., Huynh, M., Greene, S. K., Van Wye, G., Li, W., … & Shaman, J. (2021). Estimating the infection-fatality risk of SARS-CoV-2 in New York City during the spring 2020 pandemic wave: a model-based analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 21(2), 203–212.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

None to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Koppel, S., Capellan, J.A. & Sharp, J. Disentangling the Impact of Covid-19: An Interrupted Time Series Analysis of Crime in New York City. Am J Crim Just 48, 368–394 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-021-09666-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-021-09666-1