Abstract

Fear of evaluation and a negative view of the self are the core aspects of social anxiety. Self-compassion and self-esteem are two distinct positive attitudes toward the self, which are positively related to each other, well-being and good psychological functioning. It is less clear, however, how they interplay in socially anxious individuals and if self-compassion may reduce the negative effect of low self-esteem on social anxiety. The current research aimed at evaluating the directional links between those constructs to check if self-compassion mediates the effect of self-esteem on social anxiety. In this study, 388 adult participants with elevated social anxiety completed measures of self-compassion, self-esteem and social anxiety. As expected, both self-esteem and self-compassion correlated negatively with social anxiety and positively with one another, with lower self-esteem being a stronger predictor of social anxiety. Importantly, self-compassion partially mediated the relationship between self-esteem and social anxiety. These findings suggest that self-compassion partially explains the negative effects of deficits in self-esteem on social anxiety. Practical implications of the research are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) or social phobia is defined by an intense fear of social situations in which the individual may be scrutinized by others (DSM–5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). SAD is one of the most common anxiety disorders, affecting between 7 and 13% of the Western population at some point in their life (Furmark, 2002). SAD is debilitating and causes significant emotional distress and functional impairment in work and social domains including relationships (Acarturk et al., 2008). Socially anxious individuals are not only afraid of the judgment of others, whether in a negative or in a positive way (Weeks et al., 2009), but also are harsh and critical on themselves (Clark & Wells, 1995). Studies show that self-criticism is robustly associated with SAD, and socially anxious (SA) people demonstrate particularly high levels of self-criticism (Cox et al., 2004; Iancu et al., 2015).

Self-esteem (SE) refers to attitude toward oneself, including the individual’s personal self-related feelings (Sedikides & Gress, 2003). Its’ level is related to positive feelings about oneself and believing that one is valued by others (Leary & MacDonald, 2003). Self-esteem trait was found to be positively associated with various adaptive outcomes (for review see Pyszczynski et al., 2004). Low SE is associated with a lack of confidence, a tendency to avoid people, higher levels of depression, anxiety, negative mood and a decreased life satisfaction (e.g., Orth, & Robins, 2013). SE is, however, often resistant to change (Swann, 1996) and elevated self-esteem seems to be the outcome of doing well, rather than the cause of it (Baumeister et al., 2003).

Self-compassion (SC) is another positive view of the self, characterized by a caring attitude toward oneself. It is defined in terms of three main components: self-kindness in contrast to being self-critical, a sense of common humanity in contrast to a sense of isolation, and mindfulness rather than over identification when encountering personal weakness or failures (see Neff, 2003a). People high in self-compassion who encounter difficult emotions tend to offer themselves warmth, kindness and non-judgmental understanding rather than belittling their painful experiences or engaging in self-criticism. Importantly, contrary to self-esteem, it does not involve evaluations of self-worth by comparison to others or to one’s own personal standards (Neff, 2003a). Studies showed that SC is a good predictor of psychosocial adjustment (MacBeth & Gumley, 2012) while avoiding the dysfunctions that might be associated with high self-esteem such as narcissism or poor empathy (e.g., Neff et al., 2007).

Self-compassion, self-esteem and social anxiety

Low self-esteem is implied as an associate feature of social anxiety (APA, 2013) and a number of research has provided evidence to support the link between social anxiety and low self-esteem (e.g., Lowe & Harris, 2019). This should be no surprise as in core of both, social anxiety and in the pursuit of self-esteem, lies the setting of goals which validate individuals abilities, and hence their self-worth. Such inclination may cause reaction to real or potential threats in ways that could be self- sabotaging, as when success is uncertain (socially anxious people perceive success often as hard to achieve or unachievable), they may feel anxious and commit actions that decrease the probability of success by creating excuses for failure, such as self-handicapping, avoidance or procrastination (Crocker and Park, 2004). Altogether, pursuit of self-esteem and fear of negative evaluation may therefore, divert individuals from fulfilling their fundamental human needs for relatedness, competence, and autonomy, and negatively affect self-regulation leading to mental health problems such as social anxiety disorder and depression (Crocker, 2002a; Deci & Ryan, 2000).

Self-compassion, in contrast to self-esteem, does not rely on evaluations of self-worth (Neff, 2003a), and contrary to self-esteem pursuit does not have short- or long-term negative costs or consequences, but has been consistently linked with positive mental health outcomes (e.g., MacBeth & Gumley, 2012; Neff et al., 2018). Studies showed that individuals with social anxiety disorders (SAD) reported less self-compassion than healthy controls, and self-compassion was found to be negatively correlated with fear of negative evaluation, a key cognitive factor of SAD (Werner et al., 2012).

The Present Study

To our knowledge, no studies have examined, however, the interplay between self-esteem, self-compassion and social anxiety. It is possible that social anxiety severity is contingent on individuals’ abilities to be self-compassionate, which may partially explain how deficits in self-esteem translate into social anxiety. In other words, it seems plausible that part of the negative relationship between low self-esteem and social anxiety is mediated by low self-compassion. This is an important empirical question not only because of theoretical but also for practical reasons. SAD is one of the most prevalent psychiatric problems and follows a chronic and debilitating course if untreated (Acarturk et al., 2008). Still, there is space for improvement of its treatment efficacy (Mayo-Wilson et al., 2014), especially since 40 to 50% of patients with SA are not responsive to traditional cognitive behavioral therapies and effective and safe alternative therapies are needed (for meta-analysis, see: Liu et al., 2021). Although the pursuit of self-esteem has been described as a central preoccupation in Western countries for the last few decades (e.g., Baumeister et al., 2003), with hundreds of books and programs offering strategies to boost self-esteem (e.g., Glennon, 1999; McElherner & Lisovskis, 1998), its’ effectiveness is far from satisfying, as SE is resistant to change (Swann, 1996). Self-compassion, on the other side, is a skill that can be learned through targeted interventions (e.g., Bluth et al., 2017; Neff & Germer, 2013), thus could possibly be a mendable target for SA individuals’ treatment.

To answer fully the question whether self-compassion mediates the effect of low self-esteem on social anxiety a study with an experimental or longitudinal design is needed. First step, however, is to investigate the interplay between these measures in a cross-sectional study and to test if self-compassion indeed is a mediator between self-esteem and social anxiety. To date, there have been no studies that have empirically assessed the degree to which self-compassion provides an explanatory pathway for the effect of self-esteem on social anxiety. Therefore, we aimed at evaluating the directional links between those constructs within a testable model.

We examined these relationships by 1) investigating which of the two variables, self-compassion or self-esteem, contributes more to the negative relationship with social anxiety and 2) by testing if self-compassion mediates the relationship between self-esteem and social anxiety.

Method

Participants and procedure

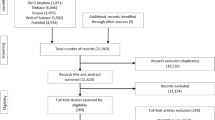

Participants included 388 Polish-speaking adults with elevated social anxiety levels (LSAS score M = 81.47, SD = 21.20). The majority were women (91%) with ages ranging from 18 to 50 years old (M = 31.97, SD = 7.41). Participants were recruited via open calls posted on the Internet, which invited them to participate in a scientific study aiming at examining adaptive self-concept. Further, the call delineated a few specific symptoms of social anxiety and asked those who fulfilled at least two of them to respond. The participants who had replied to the advertisement filled online questionnaires. The research protocol was approved by the IRB of the co-authors’ institution. All participants provided written informed consent.

Measures

The self-report version of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS-SR; Fresco et al., 2001), was used to evaluate both fear and avoidance with respect to 24 specific social situations. These include 11 social interactions (e.g., meeting strangers) and 13 performance situations (e.g., giving a prepared oral talk to a group). Participants rate fear or anxiety ranging from 0 (None) to 3 (Severe) and avoidance ranging from 0 (Never) to 3 (Usually). Cronbach's alpha for the scale in the present study was 0.88.

The Self-Compassion Scale (SCS; Neff, 2003b) is a 26-item self-report measure which employs a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Almost never) to 5 (Almost always). It assesses six facets of presence or absence of self-compassion: self-kindness, self-judgement, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness and over-identification Illustrating statement of self-compassion: “I’m kind to myself when I’m experiencing suffering.” Cronbach's alpha for the scale in the present study was 0.90.

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (SES; Rosenberg, 1965) is the most widely used self-report scale to measure levels of trait self-esteem (Gray-Little et al., 1997). It contains 10 items. A representative expression of self-esteem said, “I feel that I have a number of good qualities.” Cronbach's alpha for the scale in the present study was 0.87.

Results

Table 1 summarizes the reliabilities and descriptive statistics of all measures, together with the relationships between all the variables. The raw data are available at https://osf.io/vdc2t/.

Statistical analyses started with an examination of correlations among measures. Next, we want to examine if a negative correlation between self-esteem, self-compassion and social anxiety is mainly due to the common variance between self-esteem and self-compassion, or self-compassion share an unique variance with social anxiety. To assess the contribution of each of the two predictors in explaining social anxiety, we tested a multiple regression model.

Regression analyses are presented in Table 2. This model predicts 17.4% of social anxiety variance with self-esteem and self-compassion as significant predictors, (F (2, 385) = 40.43, p < 0.001). Self-esteem is a stronger predictor of SA than self-compassion (β = -0.324 vs β = -0.132 respectively). Hierarchical regression analysis revealed that adding self-esteem to a model based solely on self-compassion significantly improved the percentage of social anxiety variance explained from 10.6% to 17.4%, F(1, 385) = 31.39, p < 0.001.

Mediation analyses followed the framework of Baron and Kenny (1986) and rested upon the Process procedure described in Hayes (2018). Because of nonnormality of variable distributions a 1000-sample bootstrap was generated (i.e., generating 1000 samples by resampling with replacement from the current sample) for determining 95% confidence intervals that then could be used for testing the significance of correlation and regression coefficients.

The results of the Pearson correlation analysis indicated that social anxiety was negatively correlated with self-compassion: the higher the level of self-compassion, the lower the level of social anxiety (r = -0.426 ÷ -0.228, p < 0.001). Similarly, social anxiety was negatively correlated with self-esteem (r =—0.489 ÷ -0.304, p < 0.001). Self-compassion was positively correlated with self-esteem: the higher the self-compassion, the higher the self-esteem (r = 0.521 ÷ 0.663, p < 0.001).

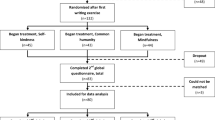

We tested the mediational model with social anxiety as the criterion variable, self-esteem as a predictor and self-compassion as a mediator. The model was significant, F(2, 385) = 40.43, p < 0.001. As Fig. 1 illustrates, the standardized regression coefficient between self-compassion and self-esteem was statistically significant, as was the standardized regression coefficient between self-esteem and social anxiety. The relationship between self-esteem and social anxiety was partially mediated by self-compassion and explained 17% in social anxiety variability (R2 = 0.17). The total (-0.50 ÷ -0.31) and the direct (-0.44 ÷ -0.21) effects of self-esteem on social anxiety were significant. We tested the significance of the indirect effect using bootstrapping procedure. Standardized indirect effects were computed for each of the 10,000 bootstrapped samples, and the 95% confidence interval was computed by determining the indirect effects at the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles. The bootstrapped standardized indirect effect 95% confidence interval ranged from -0.15 to -0.01. Thus, the indirect effect was statistically significant. Figure 1 presents the mediation.

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to assess the directional links between the constructs of self-esteem, self-compassion and social anxiety to test the main hypothesis that self-compassion mediates the negative effect of low self-esteem on social anxiety. Similarly to previous work (Neff & Vonk, 2009), we found that self-compassion and self-esteem are positively related. In accordance with the view that individuals with social anxiety tend to have a negative mental representation of the self (Rapee & Heimberg, 1997), we also found that social anxiety was negatively related to both positive attitudes toward the self, with self-esteem being a stronger predictor of social anxiety than self-compassion. These findings are in line with research showing that self-esteem (Lowe & Harris, 2019) and self-compassion (Potter et al., 2014) are significant predictors of social anxiety measures.

More importantly, we found that self-compassion partially mediates the relationship between self-esteem and social anxiety. Self-esteem implied both direct and indirect effects mediated by self-compassion on social anxiety. In similar vein, Fatima et al. (2017) reported that the relationship between self-esteem and social anxiety was mediated by social connectedness, a measure that is similar to common humanity—the subscale of self-compassion, and was previously found to correlate positively with self-compassion (Neff et al., 2007). Our findings are also broadly congruent with Marshall et al. (2015) results which showed that the longitudinal effect of self-esteem on mental health depended on self-compassion. Interestingly, recently DeLury and Poulin (2018) showed with experimental design that self-compassion as a state buffers the effect of a self-esteem threat on academic task performance. Previous studies have established that self-esteem pursuit impairs self-regulation and elevates reactivity to threatening feedback (Crocker, 2002b), as it increases the chance of interpreting events and feedback from others in terms of what it means about their self (Crocker et al., 2006), the typical attitude of socially anxious. Self-compassion, on the other hand, has been found to be capable of buffering individuals from the motivational and emotional consequences of self-esteem threats (e.g., DeLury & Poulin, 2018; Neff et al., 2005). The current research adds to this growing literature an indication that self-compassion, understood as disposition, can partially mediate (not only moderate) negative effect of self-esteem, self-worth contingent on competition and appearance, on social anxiety. It seems, that self-compassionate people are able to recognize that making mistakes and being imperfect are parts of the shared human experience not a personal defect – a typical core belief held by socially anxious, and so when feelings of inadequacy arise, a frequent phenomenon in SA, they can meet it with a greater sense of calm and security. It could be argued that self-compassion helps in addition to maintain a more balanced and rational stance toward adversities, which may keep anxiety at a lower level. Indeed, a recent study found the evidence that SC was incompatible with the irrational beliefs of self-worth and low frustration tolerance, and moreover it explained the positive linkages of self-esteem with these two irrationalities (Stephenson et al., 2018).

More broadly, the present findings point to the increasing evidence that self-compassion may act as a protective factor (see also Bluth & Neff, 2018; MacBeth & Gumley, 2012). Neff et al. (2018) for example demonstrated that self-compassion significantly predicts well-being (50 different outcome measures) almost in all areas of functioning, psychopathology, positive psychological health, emotional intelligence, self-concept, body image, motivation, and interpersonal functioning, with exception to empathy.

Previous research found that fostering self-compassion is an important process in reducing shame and self-criticism among people with social anxiety disorder (Boersma et al., 2015). The results of the present study similarly suggest that enhancing self-compassion could be beneficial for reducing symptoms of SAD. As self-compassion is a skill that can be learned through mindfulness and compassion-based interventions (e.g., Neff & Germer, 2013), it brings hope to increase the effectiveness of treatment for this debilitating and frequent mental health problem. Future studies should, however, examine this prediction in an experimental manner.

The current research has several limitations. First, all conclusions were based on correlational data including mediation analyses, precluding inferences about causation. Future work should assess in experimental or longitudinal with three points of measurements design if interventions aiming at improving self-compassion lead to an alleviation of social anxiety. Second, the studied group comprises of individuals high in social anxiety distinguished on the basis of elevated scores in a popular self-report measure of social anxiety. Future work would benefit from including individuals with a formal diagnosis of SAD. Lastly, the majority of the sample being women means that the results should be replicated on a more diverse sample.

Notwithstanding these considerations, our findings suggest that self-compassion plays an important role in buffering against social anxiety in individuals with low self-esteem, and indicate an avenue for future studies employing experimental design to verify this hypothesis.

Data Availability

The dataset is available at https://osf.io/vdc2t/.

References

Acarturk, C., de Graaf, R., van Straten, A., Have, M. T., & Cuijpers, P. (2008). Social phobia and number of social fears, and their association with comorbidity, health-related quality of life and help seeking: a population-based study. Social Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43, 273–279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-008-0309-1.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Author.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173.

Baumeister, R. F., Campbell, J. D., Krueger, J. I., & Vohs, K. D. (2003). Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4, 1–44.

Bluth, K., & Neff, K. D. (2018). New frontiers in understanding the benefits of self-compassion. Self and Identity, 17(6), 605–608.

Bluth, K., Campo, R. A., Futch, W. S., & Gaylord, S. A. (2017). Age and gender differences in the associations of self-compassion and emotional well-being in a large adolescent sample. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(4), 840–853.

Boersma, K., Håkanson, A., Salomonsson, E., & Johansson, I. (2015). Compassion focused therapy to counteract shame, self-criticism and isolation. A replicated single case experimental study for individuals with social anxiety. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 45(2), 89–98.

Clark, D. M., & Wells, A. (1995). A cognitive model of social phobia. In R. G. Heimberg, M. R. Liebowitz, D. A. Hope, & F. R. Schneier (Eds.), Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment (pp. 69–93). The Guilford Press.

Cox, B. J., Fleet, C., & Stein, M. B. (2004). Self-criticism and social phobia in the US National Comorbidity Survey. Journal of Affective Disorders, 82, 227–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.012.

Crocker, J. (2002a). Contingencies of self-worth: Implications for self-regulation and psychological vulnerability. Self and Identity, 1, 143–149.

Crocker, J. (2002b). The costs of seeking self-esteem. Journal of Social Issues, 58, 597–615.

Crocker, J., & Park, L. E. (2004). The costly pursuit of self-esteem. Psychological Bulletin, 130(3), 392.

Crocker, J., Brook, A. T., Niiya, Y., & Villacorta, M. (2006). The pursuit of self-esteem: Contingencies of self-worth and self-regulation. Journal of Personality, 74, 1749–1772.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227–268.

DeLury, S. S., & Poulin, M. J. (2018). Self-compassion and verbal performance: Evidence for threat-buffering and implicit self-related thoughts. Self and Identity, 17(6), 710–722.

Fatima, M., Niazi, S., & Ghayas, S. (2017). Relationship between Self-Esteem and Social anxiety: Role of Social Connectedness as a Mediator. Pakistan Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 15(2), 12–17.

Fresco, D. M., Coles, M. E., Heimberg, R. G., Liebowitz, M. R., Hami, S., Stein, M. B., & Goetz, D. (2001). The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale: A comparison of the psychometric properties of self-report and clinician-administered formats. Psychological Medicine, 31, 1025–1035.

Furmark, T. (2002). Social phobia: overview of community surveys. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 105(2), 84–93.

Glennon, W. (1999). 200 ways to raise a girl’s self-esteem. Conari Press.

Gray-Little, B., Williams, V. S. L., & Hancock, T. D. (1997). An item response theory analysis of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(5), 443–451.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. Guilford Press.

Iancu, I., Bodner, E., & Ben-Zion, I. Z. (2015). Self esteem, dependency, self-efficacy and self-criticism in social anxiety disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 58, 165–171.

Leary, M. R., & MacDonald, G. (2003). Individual differences in self-esteem: A review and theoretical integration. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (pp. 401–418). Guilford Press.

Liu, X., Yi, P., Ma, L., Liu, W., Deng, W., Yang, X., Liang, M., Luo, J., Li, N., & Li, X. (2021). Mindfulness-based interventions for social anxiety disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 300, 113935.

Lowe, J., & Harris, L. M. (2019). A comparison of death anxiety, intolerance of uncertainty and self-esteem as predictors of social anxiety symptoms. Behaviour Change, 36(3), 165–179.

MacBeth, A., & Gumley, A. (2012). Exploring compassion: A meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(6), 545–552.

Marshall, S. L., Parker, P. D., Ciarrochi, J., Sahdra, B., Jackson, C. J., & Heaven, P. C. L. (2015). Self-compassion protects against the negative effects of low self-esteem: A longitudinal study in a large adolescent sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 74, 116–121.

Mayo-Wilson, E., Dias, S., Mavranezouli, I., Kew, K., Clark, D. M., Ades, A. E., & Pilling, S. (2014). Psychological and pharmacological interventions for social anxiety disorder in adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(5), 368–376.

McElherner, L. N., & Lisovskis, M. (1998). Jumpstarters: Quick class-room activities that develop self-esteem, creativity, and cooperation. Free Spirit Press.

Neff, K. D. (2003a). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude towards oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85–101.

Neff, K. D. (2003b). Development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2, 223–250.

Neff, K. D., & Vonk, R. (2009). Self-compassion versus global self-esteem: Two different ways of relating to oneself. Journal of Personality, 77(1), 23–50.

Neff, K. D., & Germer, C. K. (2013). A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(1), 28–44.

Neff, K. D., Hsieh, Y. P., & Dejitterat, K. (2005). Self-compassion, achievement goals, and coping with academic failure. Self and Identity, 4(3), 263–287.

Neff, K. D., Kirkpatrick, K. L., & Rude, S. S. (2007). Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(1), 139–154.

Neff, K. D., Long, P., Knox, M. C., Davidson, O., Kuchar, A., Costigan, A., ... Breines, J. G. (2018). The forest and the trees: Examining the association of self-compassion and its positive and negative components with psychological functioning. Self and Identity, 17(6), 627–645.

Orth, U., & Robins, R. W. (2013). Understanding the link between low self-esteem and depression. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(6), 455–460.

Potter, R. F., Yar, K., Francis, A. J. P., & Schuster, S. (2014). Self-compassion mediates the relationship between parental criticism and social anxiety. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 14(1), 33–43.

Pyszczynski, T., Greenberg, J., Solomon, S., & Schimel, J. (2004). Why do people need self-esteem? A theoretical and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin, 130(3), 435–468.

Rapee, R. M., & Heimberg, R. G. (1997). A cognitive-behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35, 741–756.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press.

Sedikides, C., & Gress, A. P. (2003). Portraits of the self. In M. A. Hogg & J. Cooper (Eds.), Sage handbook of social psychology (pp. 110–138). Sage.

Stephenson, E., Watson, P. J., Chen, Z. J., & Morris, R. J. (2018). Self-compassion, self-esteem, and irrational beliefs. Current Psychology, 37(4), 809–815.

Swann, W. B. (1996). Self-Traps: The Elusive Quest for Higher Self-Esteem W. H. Freeman.

Werner, K. H., Jazaieri, H., Goldin, P. R., Ziv, M., Heimberg, R. G., & Gross, J. J. (2012). Self-compassion and social anxiety disorder. Anxiety Stress Coping, 25(5), 543–558.

Weeks, J. W., Rodebaugh, T. L., Heimberg, R. G., Norton, P. J., & Jakatdar, T. A. (2009). To avoid evaluation, withdraw: Fears of evaluation and depressive cognitions lead to social anxiety and submissive withdrawal. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 33, 375–389.

Funding

Research was partially funded by the National Science Centre (Grant 2015/19/B/HS6/02216) to the last author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

The responsible Ethics Committees approved the present study.

Consent to participate

All participants were properly instructed and gave online their informed consent to participate.

Consent for publication

All participants were properly instructed that data gained in the present study will be used for publication in an anonymous form and gave online their informed consent for publication.

Conflicts of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there are no conflicts of interest or competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Holas, P., Kowalczyk, M., Krejtz, I. et al. The relationship between self-esteem and self-compassion in socially anxious. Curr Psychol 42, 10271–10276 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02305-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02305-2