Abstract

Using a large sample of monthly gross flows from 1997 to 2003, we uncover several previously undocumented regularities in investor behavior. First, investor purchases and sales produce fund-level gross flows that are highly persistent. Persistence in fund flows dominates performance as a predictor of future fund flows. More importantly, failing to account for flow persistence leads to incorrect inferences with respect to the relation between performance and flows. Second, we document that investors react differently to performance depending on the type of fund, and that investor trading activity produces meaningful differences in the persistence of fund flows across mutual fund types. Third, at least some investors appear to evaluate and respond to mutual fund performance over much shorter time spans than previously assessed. Additionally, we document differences in the speed and magnitude of investors’ purchase and sales responses to performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Patel et al. (1994), Fant and O’Neal (2000), and Del Guercio and Tkac (2002) find autocorrelation in annual net flows. Johnson (2007) examines autocorrelation in daily flows. Warther (1995) examines the autocorrelation in annual aggregate net cash flows. However, none of these studies assesses the impact of flow persistence on the performance flow relation.

Ivkovich and Weisbenner (2006) explicitly exclude multiple transactions (by a given investor) from their sample.

A hybrid fund is a fund that invests in a mix of equity and debt.

Del Guercio and Tkac (2007) examine the effect of changes in a fund’s Morningstar ranking to its monthly fund flows, and find that a decline (increase) in fund’s ranking is followed by a decline (increase) in flows the following months. Johnson (2007) provides some evidence on monthly performance flow relation, but Johnson’s sample is drawn from about ten funds within a single family, making it unclear if the results would hold generally. Johnson (2007) notes that “Only future research can definitively address this concern”. Warther (1995) analyzes the monthly and quarterly return-flow relation between sector/industry returns and aggregate flows into funds that follow that sector/industry. Edelen and Warner (2001) conduct a similar study at a semi-weekly and daily frequency. Goetzmann and Massa (2003) analyze the relation between S&P 500 spot return and the flows to three index funds, however it is hard to generalize their results, since their sample only comprises of index funds. Our study is different from that of Warther (1995), Edelen and Warner (2001), and Goetzmann and Massa (2003) in that it examines how individual fund performance affects flows into and out of the fund.

As we discuss later, Johnson (2007) documents what appears to be a non-decaying lagged response in monthly net flows to prior performance (see his Table I). We suggest that the difference between our findings and Johnson’s arise because we explicitly control for persistence in flows whereas Johnson does not.

We select this time period as electronic N-SAR filings were not mandatory until 1997.

Specifically, we take the end-of-period total net assets and adjust this by the fund’s monthly return reported by CRSP in order to derive the next five fund size observations. Alternatively, we also scale our dollar flows by the size reported on the preceding N-SAR, as well as the average of the size reported on the preceding and current N-SAR. Our results are unchanged. Additionally, we calculate net flows following Sirri and Tufano (1998), where net flows are calculated as {TNAt – [TNAt-1 * (1 + Returnt)]} / TNAt-1. We again find qualitatively similar results.

This is consistent with prior studies examining gross flows, such as O’Neal (1997).

The calculation of these variables is presented in Section 2.2.

We note that the CRSP reported returns are gross returns. We find qualitatively similar results using returns net of expenses.

The Fama French three factors and the momentum factor were downloaded from Kenneth French’s website: http://mba.tuck.dartmouth.edu/pages/faculty/ken.french/data_library.html.

The factors are excess returns from Morgan Stanley Capital International’s All Country Index, obtained from Datastream and the Broad Trade Weighted Exchange Index obtained from the St. Louis Fed Database (FRED).

The factors represent the term structure of interest rates, credit and liquidity spreads, exchange rates, mortgage spread and two equity market benchmarks. These factors are from CRSP, FRED and The Chicago Board of Trades.

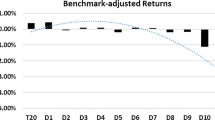

Prior research suggests the relation between performance and flows is convex. To ensure that our findings are not distorted by the imposed linearity, we rerun our analysis allowing for a non-linear performance flow relationship. We included the square of all lagged abnormal returns, as well as follow Sirri and Tufano (1998), where we rank fund performance, and split the ranking into 20-60-20 fractile buckets. Controlling for potential non-linearities does not change any of our inferences.

Our choice of 12 lags of flows and returns is ad hoc, but does allow us to capture potential seasonality in flows as well as a delayed response to fund performance.

We note, however, that the coefficient on the nine-month lag of returns is statistically insignificant.

Johnson (2007) examines the relation between net flows and the fund prior six months of returns (without controlling for lagged net flows). Consistent with our column 1, he finds relatively consistent return coefficients.

We multiply the outflow dollar amounts by negative one. This turns outflows from positive numbers to negative numbers and, thus, makes outflows negative inflows.

A natural conclusion is that observed relations between annual performance and subsequent annual flows could be a manifestation of persistent responses to monthly performance. We do not pursue that possibility in this paper.

A detailed description of the econometric properties of ARDL models is given in Chapter 19 of Greene’s (2002) textbook.

We focus on inflows because there is little relation between performance and outflows across the three fund types.

To conserve space, we do not report in figures or tables the results of our robustness checks. They are available from the authors upon request.

Specifically, we compute White standard errors adjusted to account for possible correlation across funds. Petersen (2006), among others, refers to these standard errors as clustered (or, Rogers) standard errors, where the clustering is across funds at a given point in time or, alternatively, across time for each fund.

The number of moment conditions is proportional to both the number of exogenous regressors and to the number of time series observations. With a dataset like ours, one is quite likely to face a bias/efficiency trade-off when using dynamic panel methods. See Baltagi, Chapter 8.7 for a thorough discussion of this point.

For International Equity funds and Hybrid funds, the significance patterns for net flows, inflows and outflows arrived at by clustering across funds did not change compared to those arrived at with White’s correction, although the magnitude of the clustered standard errors was much larger. For Domestic Equity funds, fewer performance lags were significant for inflows and net flows with the standard errors clustered across funds than with White’s.

By the end of 2010, these types of retirement accounts held 40 % of mutual fund assets (Investment Company Institute (2011)).

This point is consistent with the historical evolution of studies on mutual fund advisors’ ability to consistently generate abnormal returns. That line of research almost always considers growth equity funds and largely ignores the possibility of managerial ability and performance persistence in fixed-income funds (An exception is Chen et al. (2008) who look at the timing ability of bond fund managers). There is no obvious reason why, if one is in search of evidence of consistent abnormal returns that you should focus so exclusively on growth equity funds. If we assume an equal distribution of ability across the whole mutual fund environment, consistent abnormal returns are just as likely in fixed-income funds as they are in equity funds. Thus, it appears that finance academics, like actual mutual fund investors, may believe that ability is unequally distributed across mutual fund types.

Busse (2001) and Goriaev et al. (2005) are unable to find any evidence of risk-shifting within a year. Chen and Pennacchi (2009) find some evidence of changes in tracking error related to prior performance. Koski and Pontiff (1999) also find a negative relation between performance over the first part of a year and risk over the remainder of the year. Unlike Chevalier and Ellison (1997) and Brown et al. (1996), Koski and Pontiff attribute the risk to cash inflows resulting from good performance over the first part of the year.

References

Ahn S, Schmidt P (1995) Efficient estimation of models for dynamic panel data. J Econ 68:5–28

Alexander GJ, Cici G, Gibson S (2007) Does motivation matter when assessing trade performance? An analysis of mutual funds. Rev Financ Stud 20:125–150

Arellano M, Bond SR (1991) Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte-Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev Econ Stud 38:277–297

Arellano M, Bover O (1995) Another look at instrumental-variable estimation of error-components models. J Econ 68:29–52

Baltagi BH (2001) Econometric analysis of panel data. Wiley, New York

Bergstresser D, Poterba J (2002) Do after-tax returns affect mutual fund inflows? J Financ Econ 63:381–414

Berk JB, Green RC (2004) Mutual fund flows and performance in rational markets. J Polit Econ 112:1269–1295

Brown KC, Harlow WV, Starks LT (1996) Of tournaments and temptations: an analysis of managerial incentives in the mutual fund industry. J Finance 51:85–110

Busse JA (2001) Another look at mutual fund tournaments. J Financ Quant Anal 36:53–73

Chen Hsiu-lang, Pennacchi GG (2009) Does prior performance affect a mutual fund’s choice of risk? Theory and further empirical evidence. J Financ Quant Anal 44:745–775

Chen Y, Ferson W, Peters H (2008) Measuring the timing ability of fixed income mutual funds, working paper, Boston College

Chevalier J, Ellison G (1997) Risk taking by mutual funds as a response to incentives. J Polit Econ 105:1167–1200

Christoffersen S, Evans R, Musto D (2005) The economics of mutual fund brokerage: evidence from the cross section of investment channels, working paper

Cochrane JH (2001) Asset pricing. Princeton University Press, New Jersey

Cohen L, Schmidt B (2009) Attracting flows by attracting big clients. J Finance 64:2125–2151

Del Guercio D, Tkac PA (2002) The determinants of the flow of funds of managed portfolios: mutual funds vs. pension funds. J Financ Quant Anal 37:523–557

Del Guercio D, Tkac PA (2007) Star power: The effect of Morningstar ratings on mutual fund flows, working paper, University of Oregon

DeSantis G, Gerard B (1998) How big is the risk premium for currency risk. J Financ Econ 49:375–412

Dumas B, Solnik B (1995) The world price of foreign exchange risk. J Finance 2:445–479

Edelen RM (1999) Investor flows and the assessed performance of open-end mutual funds. J Financ Econ 53:439–466

Edelen RM, Warner JB (2001) Aggregate price effects of institutional trading: a study of mutual fund flow and market returns. J Financ Econ 59:195–220

Fama E, French KR (2002) Testing tradeoff and pecking order predictions about dividends and debt. Rev Financ Stud 15:1–33

Fama EF, MacBeth JD (1973) Risk, return and equilibrium: empirical tests. J Polit Econ 81:607–636

Fant F, O’Neal E (2000) Temporal changes in the determinants of mutual fund flows. J Financ Res 23:353–371

Goetzmann WN, Massa M (2003) Index funds and stock market growth. J Bus 76:1–28

Goriaev A, Nijman TE, Werker BJM (2005) Yet another look at mutual fund tournaments. J Empir Finance 12:127–137

Graham J, Lemmon M, Schallheim J (1998) Debt, leases, taxes and the endogeneity of corporate tax status. J Finance 53:131–162

Greene WH (2002) Econometric analysis. Prentice Hall, New Jersey

Investment Company Institute (2006) Fact book. Investment Company Institute, Washington, D.C

Investment Company Institute (2009) Fact book. Investment Company Institute, Washington, D.C

Investment Company Institute (2011) Fact book. Investment Company Institute, Washington, D.C

Ivkovich Z, Weisbenner SJ (2006) ‘Old’ money matters: the sensitivity of mutual fund redemption decisions to past performance, working paper, University of Illinois

Johnson WT (2007) Who monitors the mutual fund manager, new or old shareholders?, working paper, University of Oregon

Keswani A, Stolin D (2008) Which money is smart? Mutual fund buys and sells of individual and institutional investors. J Finance 63:85–118

Koski JL, Pontiff J (1999) How are derivatives used? Evidence from the mutual fund industry. J Finance 54:791–816

Nanda V, Jay Wang Z, Zheng Lu (2009) The ABCs of mutual funds: on the introduction of multiple share classes. J Financ Intermediation 18:329–361

O’Neal E (1997) How many mutual funds constitute a diversified mutual fund portfolio? Financ Anal J 53:37–46

Patel J, Zeckhauser RJ, Hendricks D (1994) Investment flows and performance: evidence from mutual funds, cross-border investments and new issues. In: Satl R, Levitch R, Ramachandran R (eds) Japan, Europe and the International financial markets: analytical and empirical perspectives. Cambridge University Press, New York

Petersen MA (2006) Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: comparing approaches, working paper, Northwestern University

Pontiff J (1996) Costly arbitrage: evidence from closed-end funds. Q J Econ 111:1135–1151

Sirri ER, Tufano P (1998) Costly search and mutual fund flows. J Finance 53:1589–1622

Warther VA (1995) Aggregate mutual fund flows and security returns. J Financ Econ 39:209–235

Wooldridge J (2002) Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT Press, Cambridge

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix A

Appendix A

We use Standard and Poor’s classification to group funds into four major categories. Listed below are the categories, and the Standard & Poor’s codes and their descriptions belonging to each category:

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cashman, G.D., Nardari, F., Deli, D.N. et al. Investor behavior in the mutual fund industry: evidence from gross flows. J Econ Finan 38, 541–567 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12197-012-9231-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12197-012-9231-1