Abstract

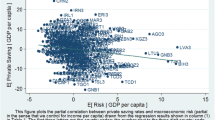

This paper estimates the effect of income uncertainty on assets held in accounts and cash, and finds substantial empirical evidence for precautionary savings. Using household-level panel data, it explicitly distinguishes between ‘real’ income uncertainty the household is actually exposed to, and ‘perceived’ income uncertainty. It finds that the latter substantially increases precautionary savings above and beyond the effect of ‘real’ income uncertainty. The effect of subjective economic uncertainty on behaviour has only begun to show up after the Great Recession. The economic crisis appears to have shifted households’ willingness to forgo current consumption for insurance pruposes. Our results imply that households save above their optimal level especially after and during a crisis, potentially exacerbating the economic downturn.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Benhabib and Bisin (2005) develop a neuroeconomic life-cycle model based on the assumption that a consumer can decide to override his/her automatic consumption choices with a cognitively controlled choice. This is related to the concept of mastery or locus of control (that is the belief that one can oneself affect one’s future economic outcomes) which has been shown empirically to affect wealth accumulation (Cobb-Clark et al. 2013). Exercising such self-restraint, however, is costly.

This should be particularly important for low-income households that struggle to build up sufficient savings; those households often rely on increased unsecured debt in the event of unemployment (see Sullivan 2008). Low-income household’s reliance on (typically expensive) unsecured debt could have long-term, undesirable distributional effects.

The level of wealth at any given point in time is the result not only of a series of behavioural choices, but also of a history of income shocks, starting conditions, and luck in terms of investment returns.

For detailed information on the HILDA Study, its survey design and collected information see Summerfeld et al. (2015).

The data was extracted using PanelWhiz, software that provides a graphical interface for assessing many panel data sets from around the world in Stata. Haisken-DeNew and Hahn (2010) provide a general introduction to the use of PanelWhiz, and Hahn and Haisken-DeNew (2013) discuss the software’s usage specifically for Australian datasets including HILDA.

This leaves a sample of one-family households, where this family is a couple-family with or without children, a lone-parent-family or a lone person without children.

The income or asset information is considered implausible, a) if the household’s reported unsecured debt exceeds $200,000 and exceeds twice the annual household income, or b) if household overall assets minus debt exceed 50 times the annual household income. The reported household income is considered implausible if it is less than 75% of the minimum income support payable to a couple or lone person, respectively. These restrictions drop a total of 155 observations.

We also estimated a version of equation (1) with added household fixed effects to control unobserved heterogeneity. The results do not change. However, panel attrition reduces the sample available for the fixed effects estimation. We thus prefer the cross-sectional estimates and present them in this paper; the panel estimates are available on request.

This imputation procedure is, although drawing on two different data sets, conceptually similar to a two-stage instrument variable estimation, and the prediction of expectations can be interpreted to represent the “first-stage” estimation results, while the main estimation of equation (1) represents the “second stage”. In that sense, our analysis follows Lusardi (1997) and Mastrogiacomo and Alessie (2014) who use instruments to deal with attenuation bias in measures of subjective uncertainty. The ‘first stage’-estimation includes controls for state of residence, age, gender, occupation, education, household size, income and year; these characteristics are also controlled in the “second stage” - the main estimation of equation (1) (Xitand lyitT), with the exception of gender. In addition, the probability of losing one’s job, leaving it voluntarily and finding a new one at least as good, as well as one’s self-rated financial situation compared to last year’s, are included in the first stage, but excluded from the second stage. For this strategy to be valid, these “instruments” must, first, be strongly correlated with economic expectations, and second, the household’s subjective assessment of the future state of the economy must be the only link between the “instruments” and the household’s savings rate. The F-statistic for a test on joint significance of these variables in the first stage is 68.10 (see Table 1), indicating that the first criterion is indeed fulfilled. In order to fulfil the second condition, a number of other crucial variables have to be controlled in the second stage: in particular variables that describe the households’ past and future real financial situation. As already discussed in Section 2, the estimation equation (1) will include current assets held in accounts and acit, other wealthln(wealthit), future income lyitT, and the variance of future income lvarlyitTto ensure that these conditions hold.

Income is transformed into 2014 Australian dollars using the Consumer Price Indices provided by the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Where income information is not available in one or two of the four waves, it is assumed to be equal to the average household income as calculated from the waves for which the information was available. If income was missing in more than two of the four waves, observations have been removed from the sample. The within-household variance of income is calculated using true income observations only.

We have run robustness checks that additionally include the number of dependent children. Results do not change and are available from the authors on request.

This includes individually as well as jointly owned cheque accounts, savings accounts, keycard/EFTPOS accounts, other transaction accounts, fixed term deposits and cash management trusts.

All asset components have been transformed into 2014 Australian dollars using the Consumer Price Indices provided by the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

A number of items are missing in less than 1% of all cases; these are rare items for which most individuals indicate to not have this asset type or debt category at all: cash investments, and the value of and debt on investment properties. For somewhat more commonly held assets and debt categories, exact values are missing in more than 1% and less than 5% of all cases; these are the value of and debt on an owner-occupied home, the value of businesses, collectibles and vehicles, as well as the financial assets “equity investments”, “life insurance” and “trust funds”. The most commonly held types of assets and debt, which are missing in more than 5% of all cases, are positive and negative balances on bank accounts and credit card accounts, other forms of personal debt (including unpaid household bills), and pension savings. Among these categories, values are missing for 7.9% (other debt) to 18.3% (pension savings) of all observations.

Evaluated at all other variables set to zero, this would imply a cash savings rate of 5.7%, which is substantially higher than the empirical observed value of 1.5%. However, a household with all controlled characteristics at zero does not exist in the data.

To explore which of the two explanations is likely at play, we repeated the estimation adding a dummy-variable that indicates whether a household is currently paying off a mortgage. In that specification, the coefficient on non-financial assets is reduced by about 50% and becomes insignificant at the 10%-level; at the same time, households that currently pay off a mortgage are observed to accumulate on average 1.26 percentage points more cash relative to their income than other households. However, the underlying estimated coefficient is insignificant at the 10%-level.

We also estimate a fully interacted model, in which not only subjective and objective economic uncertainty, but also all control variables are interacted with the set of year dummies. The results on key coefficients (subjit and lvarlyitT) are robust to this change and available from the authors.

While this is not a measure of intelligence per se, the test’s predictive power for general intelligence tests is very high. The main advantage of this test compared to more direct measures of intelligence is that it is quick to administer in a survey setting.

References

Agarwal S, Mazumder B (2013) Cognitive abilities and household financial decision making. Am Econ J Appl Econ 5:193–207

Benhabib J, Bisin A (2005) Modelling internal commitment mechanisms and self-control: a neuroeconomics approach to consumption--saving decisions. Games and Economic Behavior 52:460–492

Carroll CD, Samwick AA (1998) How important is precautionary saving? Review of Economics and Statistics 80:410–419

Carroll CD, Hall RE, Zeldes SP (1992) The buffer-stock theory of saving: some macroeconomic evidence. Brook Pap Econ Act 1992(2):61–156

Carroll CD, Slacalek J, Sommer M (2012) Dissecting saving dynamics: measuring wealth, precautionary, and credit effects. John Hopkins University, Manuscript http://econ.jhu.edu/people/ccarroll/papers/cssUSSaving/

Christelis D, Jappelli T, Padula M (2010) Cognitive abilities and portfolio choice. Eur Econ Rev 54:18–38

Cobb-Clark DA, Schurer S (2012) The stability of big-five personality traits. Econ Lett 115:11–15

Cobb-Clark DA, Kassenboehmer SC, Sinning M (2013) Locus of control and savings. Ruhr economic paper 455. Ruhr University Bochum (RUB), Bochum

Engen EM, Gruber J (2001) Unemployment insurance and precautionary saving. J Monet Econ 47:545–579

Finlay R (2012) The distribution of household wealth in Australia: evidence from the 2010 HILDA survey. RBA Bulletin:19–27

Guiso L, Jappelli T, Terlizzese D (1992) Earnings uncertainty and precautionary saving. J Monet Econ 30:307–337

Guiso L, Sapienza P, Zingales L (2008) Trusting the stock market. J Financ 63:2557–2600

Hahn MH, Haisken-DeNew JP (2013) Panelwhiz and the Australian longitudinal data infrastructure in economics. Australian Economic Review 46:379–386

Haisken-DeNew JP, Hahn MH (2010) Panelwhiz: efficient data extraction of complex panel data sets-an example using the German SOEP. Journal of Applied Social Science Studies 130:643–654

Hayes C , Watson N (2009) HILDA imputation methods. HILDA project technical paper 2/09, Melbourne: Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, University of Melbourne

Hurst E, Lusardi A, Kennickell A, Torralba F (2010) The importance of business owners in assessing the size of precautionary savings. Rev Econ Stat 92:61–69

Kazarosian M (1997) Precautionary savings a panel study. Review of Economics and Statistics 79:241–247

Laibson D (1997) Golden eggs and hyperbolic discounting. Q J Econ 112:443–477

Little RJA, Su HL (1989) Item nonresponse in panel surveys. In: Kasprzyk D, Duncan G, Kalton G, Singh MP (eds) Panel surveys. Wiley, New York, pp 400–425

Lusardi A (1997) Precautionary saving and subjective earnings variance. Econ Lett 57:319–326

Lusardi A (1998) On the importance of the precautionary saving motive. Am Econ Rev 88:449–453

Mastrogiacomo M, Alessie R (2014) The precautionary savings motive and household savings. Oxf Econ Pap 66:164–187

Mody A, Ohnsorge F, Sandri D (2012) Precautionary savings in the great recession. IMF Economic Review 60:114–138

OECD (2015) National accounts at a glance 2015. OECD Publishing

Saucier G (1994) Mini-markers: A brief version of Goldberg's unipolar big-five markers. J Pers Assess 63:506–516

Smith JP, McArdle JJ, Willis R (2010) Financial decision making and cognition in a family context. Econ J 120:F363–F380

Sullivan JX (2008) Borrowing during unemployment - unsecured debt as a safety net. J Hum Resour 43:383–412

Summerfeld M, Freidin S, Hahn M, Li N, Macalalad N, Mundy L, Watson N, Wilkins R, Wooden M (2015) HILDA user manual release 14. Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, University of Melbourne, Melbourne

Ventura L, Eisenhauer JG (2006) Prudence and precautionary saving. J Econ Financ 30:155–168

Wilkins, Roger, 2013. The distribution and dynamics of household net wealth. Families, Incomes and Jobs Volume 8 - A Statistical Report on Waves 1 to 10 of the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey: 73--81. Melbourne: Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, University of Melbourne

Wooden, Mark, 2013. The measurement of cognitive ability in wave 12 of the HILDA survey. HILDA project discussion paper 1/13, Melbourne: Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, University of Melbourne

Acknowledgements

The research reported on in this paper is part of the Australian Research Council (ARC) funded Discovery Project `Subjective Expectations and Economic Behaviour’ (Grant DP130103755, awarded to John Haisken-DeNew). Access to the Consumer Attitudes, Sentiments & Expectations (CASiE) Survey was graciously provided by Guay Lim at the the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research (Melbourne Institute). The paper uses the general release file of the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey. The unit record data from the HILDA Survey can be obtained from the Australian Data Archive, which is hosted by The Australian National University (ANU). The HILDA survey was initiated and is funded by the Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS) and managed by the Melbourne Institute. The findings and views reported in this paper are those of the authors alone and should not be attributed to the Australian Government, DSS, the Australian Data Archive, the ARC, ANU or the Melbourne Institute, and none of those entities bear any responsibility for the analysis or interpretation of the unit record data from the HILDA Survey provided by the authors. We thank Melisa Bubonya, Bob Gregory, Arvid Hoffman, Sonja Kassenboehmer, Viet Nguyen, Davud Rostam-Afschar as well as participants at the 2017 Conference of the European Economic Association in Lisboa, the 2016 European Society for Population Economics Conference in Berlin, the 2016 Hepburn Springs Workshop, and the Department of Economics Seminar Series at Deakin University for helpful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix - Cognitive and non-cognitive skills

Appendix - Cognitive and non-cognitive skills

There are several cognitive and non-cognitive skills indicators for which we control in the estimation of wealth accumulation strategies. The lower panel of Table 3 shows all cognitive and non-cognitive indicators that are included in the estimations.

First, we include cognitive skills in the estimation, which play a role in investment strategies: individuals with higher mathematical skills are less likely to make financial mistakes (Agarwal and Mazumder 2013), and higher cognitive skills are correlated with stock market participation (Christelis et al. 2010). HILDA contains three measures of cognitive skills; the tests and their implementation in HILDA are described in detail in Wooden (2013). The ‘Backwards Digit Span’ test (which is part of many intelligence tests, such as the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scales) tests respondents’ memory by reading out strings of single-digit numbers, which participants are meant to repeat in reverse order. In the ‘Symbol Digits Modalities’ test, participants match symbols to numbers using a printed key as quickly as possible. The last test gauges intelligence by assessing reading ability: participants are asked to pronounce irregularly spelled words.Footnote 20 We recode all three test scores so that the new score is a variable with mean zero and variance one; afterwards, the average of all three measures with equal weights is calculated to represent a person’s overall cognitive skills. For couples, the higher cognitive score is used to represent the couple’s cognitive skills, as Smith et al. (2010) have shown that in married couples, the spouse with higher cognitive skills is most likely the dominant financial decision maker.

A second dimension of cognitive and non-cognitive skills that has been shown to impact on wealth accumulation, and may be correlated with economic expectations, is an individual’s level of trust (Guiso et al. 2008). A loss on an investment can occur not only because of a negative development of the market, but also because of fraud; thus, an individual’s trust in the market must be sufficiently high for them to participate. HILDA provides a measure of trust in respondent’s level of agreement with the statement “Generally speaking, most people can be trusted”. Agreement or disagreement can be given on a scale from 1 to 7. For couples, the average response between both members is used to represent the couple’s level of trust.

Third, we control for an individual’s level of risk aversion when it comes to financial investment strategies. Respondents in HILDA are asked what best describes the amount of risk they are prepared to take when it comes to spare cash used to save or invest. They can then choose between the options: taking “substantial”, “above-average” or “average” risks, to earn “substantial”, “above-average” or “average” returns, or “I am not willing to take risk”. We have translated these into values from 1 to 4. For couples, we take the average. Interviewees also have the option to respond that they never have spare cash to save or invest, in which case we consider the item missing.

Finally, we include a measure of five dimensions of personality: Agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, extroversion and openness to new experiences (the ‘Big Five’). Respondents state how well 36 different adjectives describe them; the inventory of items was developed by Saucier (1994). Factor analysis is used to combine these items into five indicators, representing one personality dimension each. The indicators range from 1 to 7. Measures of personality are included in waves 2005, 2009 and 2013. We assume that personality is fixed in the medium-term (Cobb-Clark and Schurer 2012); for each personality dimension, the average level of the corresponding indicator over all available waves is used to represent a person’s personality for the entire observation period. For couples, the average indicator within each personality dimension across both couple members is used to represent the couple.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Broadway, B., Haisken-DeNew, J.P. Keep calm and consume? Subjective uncertainty and precautionary savings. J Econ Finan 43, 481–505 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12197-018-9451-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12197-018-9451-0