Abstract

Background

Participation in coronary heart disease secondary prevention programs is low. Innovative programs to meet this treatment gap are required.

Purpose

To aim of this study is to describe the effectiveness of a telephone-delivered secondary prevention program for myocardial infarction patients.

Methods

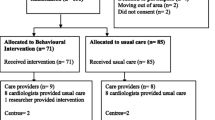

Four hundred and thirty adult myocardial infarction patients in Brisbane, Australia were randomised to a 6-month secondary prevention program or usual care. Primary outcomes were health-related quality of life (Short Form-36) and physical activity (Active Australia Survey).

Results

Significant intervention effects were observed for health-related quality of life on the mental component summary score (p = 0.02), and the social functioning (p = 0.04) and role-emotional (p = 0.03) subscales, compared with usual care. Intervention participants were also more likely to meet recommended levels of physical activity (p = 0.02), body mass index (p = 0.05), vegetable intake (p = 0.04) and alcohol consumption (p = 0.05).

Conclusions

Telephone-delivered secondary prevention programs can significantly improve health outcomes and could meet the treatment gap for myocardial infarction patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Smith Jr SC, Allen J, Blair SN, Bonow RO, Brass LM, Fonarow GC, et al. AHA/ACC guidelines for secondary prevention for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2006 Update: endorsed by the national heart, lung, and blood institute. Circulation. 2006;113(19):2363–72. May 16, 2006.

Piepoli MF, Corrà U, Benzer W, Bjarnason-Wehrens B, Dendale P, Gaita D, et al. Secondary prevention through cardiac rehabilitation: from knowledge to implementation. A position paper from the cardiac rehabilitation section of the European association of cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2010;17(1):1–17. 0.1097/HJR.0b013e3283313592.

Clark AM, Hartling L, Vandermeer B, McAlister FA. Meta-analysis: secondary prevention programs for patients with coronary artery disease. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(9):659–72. November 1, 2005.

Joliffe J, Rees K, Taylor R, Thompson D, Oldridge N, Ebrahim S. Exercise-based rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Review In: The Cochrane Library. 2003(1):1–41.

Briffa T, Kinsman L, Maiorana AJ, Zecchin R, Redfern J, Davidson PM, et al. An integrated and coordinated approach to preventing recurrent coronary heart disease events in Australia. MJA. 2009;190:683–6.

Davies P, Taylor F, Beswick A, Wise F, Moxham T, Rees K, et al. Promoting patient uptake and adherence in cardiac rehabilitation. The Cochrane Library. 2010(7).

Scott IA, Lindsay KA, Harden HE. Utilisation of outpatient cardiac rehabilitation in Queensland. Med J Aust. 2003;179(7):341–5.

Daly J, Sindone AP, Thompson DR, Hancock K, Chang E, Davidson P. Barriers to participation in and adherence to cardiac rehabilitation programs: a critical literature review. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 2002;17:8–17.

Gurewich D, Prottas J, Bhalotra S, Suaya JA, Shepard DS. System-level factors and use of cardiac rehabilitation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2008;28(6):380–5.

British Heart Foundation. National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation 2011: an annual, BHF funded report into the provision and uptake of cardiac rehabilitation across England, Wales and Northern Ireland. 2011.

Allen JK, Dennison CR. Randomized trials of nursing interventions for secondary prevention in patients with coronary artery disease and heart failure: systematic review. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010;25(3):207–20. doi:10.1097/JCN.0b013e3181cc79be.

Neubeck L, Redfern Ju, Fernandez R, Briffa T, Bauman A, Freedman SB. Telehealth interventions for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease: a systematic review. J Cardiovasc Risk. 2009;16(3):281–9. June 1, 2009.

Blair J, Corrigal H, Angus NJ, Thompson DR, Leslie S. Home versus hospital-based cardiac rehabilitation: a systematic review. Rural Remote Heal. 2011;11(2):1532–49. Apr–Jun Epub Apr 6.

Redfern J, Briffa T, Ellis E, Freedman SB. Patient-centered modular secondary prevention following acute coronary syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2008;28(2):107–15. quiz 16–7.

Stewart S, Inglis S, Hawkes A. Chronic cardiac care: A guide to specialist nurse management. London: Blackwell BMJ Books; 2006.

Worcester MUC, Le Grande MR. The role of cardiac rehabilitation in influencing psychological outcomes. Stress Heal. 2008;24(3):267–77.

Heran BS, Chen JMH, Ebrahim S, Moxham T, Oldridge N, Rees K, et al. Exercise-based rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011. doi:1002/14651858.CD001800.pub2. Issue 7. Art. No.: CD001800.

Hawkes AL, Atherton J, Taylor CB, Scuffham P, Eadie K. Houston Miller N, et al. Randomised controlled trial of a secondary prevention program for myocardial infarction patients ('ProActive Heart'): study protocol. Secondary prevention program for myocardial infarction patients. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2009;9:16–22.

National Heart Foundation of Australia and Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand. Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. MJA. 2006;184:S1–S30.

The Heart Foundation Australia Website. Available from: http://www.heartfoundation.org.au/Heart_Information/Information_by_Phone/Pages/default.aspx.

Painter JE, Borba CP, Hynes M, Mays D, Glanz K. The use of theory in health behaviour research from 2000 to 2005: a systematic review. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35:358–62.

Bandura A. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall; 1977.

Bunker SJ, Colquhoun DM, Esler MD, Hickie IB, Hunt D, Jelinek M, et al. "Stress" and coronary heart disease: psychosocial risk factors. Med J Aust. 2003;178:272–6.

National Heart Foundation of Australia and Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand. Reducing risk in heart disease: guidelines for preventing cardiovascular events in people with coronary heart disease. National Heart Foundation of Australia; 2003.

National Heart Foundation of Australia and the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand. Reducing risk in heart disease 2007 (updated 2008).

National Heart Foundation of Australia. My Heart My Life: a manual for patients with coronary heart disease. National Heart Foundation of Australia; 2007.

Hawthorne G, Osborne RH, Taylor A, Sansoni J. The SF36 version 2: critical analyses of population weights, scoring algorithms and population norms. Qual Life Res. 2007;16(4):661–73.

Dempster M, Donnelly M. Measuring the health related quality of life of people with ischaemic heart disease. Heart. 2000;83(6):641–4. June 1, 2000.

Stewart AL, Greenfield S, Hays RD, Wells K, Rogers WH, Berry SD, et al. Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions. JAMA: J Am Med Assoc. 1989;262(7):907–13. August 18, 1989.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). The Active Australia Survey: a guide and manual for implementation, analysis and reporting. Canberra: AIHW2003.

Timperio A, Salmon J, Crawford D. Validity and reliability of a physical activity recall instrument among overweight and non-overweight men and women. J Sc Med Sport/Sports Med Aust. 2003;6(4):477–91.

Heesch KC, Hill RL, van Uffelen JGZ, Brown WJ. Are active Australia physical activity questions valid for older adults? J Sci Med Sport. 2010;14(3):233–7.

Brown WJ, Trost SG, Bauman A, Mummery K, Owen N. Test–retest reliability of four physical activity measures used in population surveys. J Sci Med Sport/Sports Med Aus. 2004;7(2):205–15.

Hodge A, Patterson AJ, Brown WJ, Ireland P, Giles G. The Anti Cancer Council of Victoria FFQ: relative validity of nutrient intakes compared with weighed food records in young to middle-aged women in a study of iron supplementation. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2000;24(6):576–83.

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(11):726–32.

Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gøtzsche PC, Devereaux PJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ.340.

Hoffman BM, Babyak MA, Craighead WE, Sherwood A, Doraiswamy PM, Coons MJ, et al. Exercise and pharmacotherapy in patients with major depression: one-year follow-up of the SMILE study. Psychosom Med. 2011;73(2):127–33.

Vale MJ, Jelinek MV, Best JD, Dart AM, Grigg LE, Hare DL, et al. Coaching patients On Achieving Cardiovascular Health (COACH): a multicenter randomized trial in patients with coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(22):2775–83. December 8, 2003.

US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical activity and health: a report of the Surgeon General Atlanta, Georgia: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, CDC, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion 1996.

Goode AD, Reeves MM, Eakin EG. Telephone-delivered interventions for physical activity and dietary behavior change: an updated systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(1):81–8.

Waters LA, Reeves MM, Fjeldsoe BS, Eakin EG. Characteristics of control group participants who increased their physical activity in a cluster-randomized lifestyle intervention trial. BMC Publ Health. 2011;11:27.

Sjostrom O, Holst D. Validity of a questionnaire survey: response patterns in different subgroups and the effect of social desirability. Acta Odontol Scand. 2002;60(3):136–40.

Shephard RJ. Regression to the mean. A threat to exercise science? Sports Med. 2003;33(8):575–84.

van Sluijs EM, van Poppel MN, Twisk JW, van Mechelen W. Physical activity measurements affected participants' behavior in a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(4):404–11.

Coyne T, Ibiebele TI, McNaughton S, Rutishauser IHE, O'Dea K, Hodge AM, et al. Evaluation of brief dietary questions to estimate vegetable and fruit consumption? Using serum carotenoids and red-cell folate. Public Health Nutr. 2005;8(03):298–308.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council project grant #443222. Adrienne O’Neil is supported by a Post Graduate Award from the National Heart Foundation of Australia (PP 08 M4079). The funding bodies had no role in the design or conduct of the study, data extraction or data analyses. We thank The Prince Charles Hospital and Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital staff for their support of the study, and acknowledge the dedicated work of our health coaches, Dr Dominique Bird, Ms Brigid Hanley and Ms Bernice Kelly, as well as our telephone interviewers. We thank our research investigators, Professor Paul Scuffam, Ms Nancy Houston Miller and Professor John Bett. We are also grateful for Associate Professor Darren Walters’ support of the study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hawkes, A.L., Patrao, T.A., Atherton, J. et al. Effect of a Telephone-Delivered Coronary Heart Disease Secondary Prevention Program (ProActive Heart) on Quality of Life and Health Behaviours: Primary Outcomes of a Randomised Controlled Trial. Int.J. Behav. Med. 20, 413–424 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-012-9250-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-012-9250-5