Abstract

Background

Depression and anxiety are common in cardiac patients, and psychological interventions may also be used as part of general cardiac rehabilitation programs.

Purpose

This study aims to estimate effects of psychological interventions on mortality and psychological symptoms in this group, updating an existing Cochrane Review.

Method

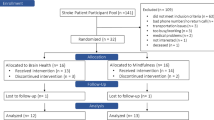

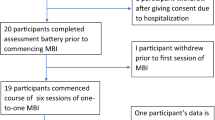

Systematic review and meta-regression analyses of randomized trials evaluating a psychological treatment delivered by trained staff to patients with a diagnosed cardiac disease, with a follow-up of at least 6 months, were used.

Results

There was no strong evidence that psychological intervention reduced total deaths, risk of revascularization, or non-fatal infarction. Psychological intervention did result in small/moderate improvements in depression and anxiety, and there was a small effect for cardiac mortality.

Conclusion

Psychological treatments appear effective in treating patients with psychological symptoms of coronary heart disease. Uncertainty remains regarding the subgroups of patients who would benefit most from treatment and the characteristics of successful interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Chung MC, Berger Z, Jones R, Rudd H. Posttraumatic stress disorder and general health problems following myocardial infarction (Post-MI PTSD) among older patients: the role of personality. Int J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2006;21(12):1163–74.

Krishnan KRR, Delong M, Kraemer H, et al. Comorbidity of depression with other medical diseases in the elderly. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(6):559–88.

Diener E, Chan MY. Happy people live longer: subjective well-being contributes to health and longevity. Appl Psychol Health Well-Being. 2011;3(1):1–43.

Stice E. Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2002;128(5):825.

Hopko DR, Mullane CM. Exploring the relation of depression and overt behavior with daily diaries. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46(9):1085–9.

Halaris A. Comorbidity between depression and cardiovascular disease. Int Angiol. 2009;28(2):92–9.

Hemingway H, Marmot M. Psychosocial factors in the aetiology and prognosis of coronary heart disease: systematic review of prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 1999;318(7196):1460–7.

Cesari M, Penninx BBWJH, Newman AAB, et al. Inflammatory markers and onset of cardiovascular events. Circulation. 2003;108(19):2317–22. Available at: http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/108/19/2317.short. Accessed February 29, 2012.

Hansson GK. Immune mechanisms in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21(12):1876–90. Available at: http://atvb.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/21/12/1876. Accessed March 26, 2012.

Mendall MA, Patel P, Asante M, et al. Relation of serum cytokine concentrations to cardiovascular risk factors and coronary heart disease. Heart. 1997;78(3):273–7.

Martin RA. Humor, laughter, and physical health: methodological issues and research findings. Psychol Bull. 2001;127(4):504.

Pasic J, Levy WC, Sullivan MD. Cytokines in depression and heart failure. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(2):181–93.

Greaves C, Sheppard K, Abraham C, et al. Systematic review of reviews of intervention components associated with increased effectiveness in dietary and physical activity interventions. BMC Publ Health. 2011;11(1):119.

Lespérance F, Frasure-Smith N. Depression in patients with cardiac disease: a practical review. J Psychosom Res. 2000;48:379–91.

Jolly K, Bradley F, Sharp S, Smith H, Mant D. Follow-up care in general practice of patients with myocardial infarction or angina pectoris: initial results of the SHIP trial. Southampton Heart Integrated Care Project. Fam Pract. 1998;15(6):548–55.

Black JL, Allison TG, Williams DE, Rummans TA, Gau GT. Effect of intervention for psychological distress on rehospitalization rates in cardiac rehabilitation patients. Psychosomatics. 1998;39(2):134–43.

Burnett-Zeigler I, Zivin K, Ilgen M, et al. Depression treatment in older adult veterans. Am J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2010.

Cepoiu M, McCusker J, Cole MG, et al. Recognition of depression by non-psychiatric physicians—a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(1):25–36.

Welton NJ, Caldwell DM, Adamopoulos E, Vedhara K. Mixed treatment comparison meta-analysis of complex interventions: psychological interventions in coronary heart disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(9):1158.

Rees K, Bennett P, West R, Davey SG, Ebrahim S. Psychological interventions for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;2:CD002902.

DeBusk RF, Miller NH, Superko R, et al. A case-management system for coronary risk factor modification after acute myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:721–9.

Erdman RAM, Duivenvoorden HJ. Psychologic evaluation of a cardiac rehabilitation program: a randomized clinical trial in patients with myocardial infarction. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 1983;3(10):696–704.

Fridlund B, Hogstedt B, Lidell E, Larsson PA. Recovery after myocardial infarction: effects of a caring rehabilitation programme. Scand J Caring Sci. 1991;5(1):23–32.

Linden W, Phillips MJ, Leclerc J. Psychological treatment of cardiac patients: a meta-analysis. Eur Hear J. 2007;28(24):2972–84.

ENRICHD. Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease (ENRICHD) study intervention: rationale and design. Psychosom Med. 2001;63(5):747–55.

Butler A, Chapman J, Forman E, Beck A. The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26(1):17–31.

Abraham C, Michie S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Heal Psychol. 2008;27(3):379.

Wilson C, Huston T, Koval J, et al. SCIRehab Project series: the psychology taxonomy. J Spinal Cord Med. 2009;32(3):319.

Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2011;343:d5928. Available at: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3196245&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. Accessed March 19, 2012.

Cochrane. Preferred method for handling continuous variables. 2003. Available at: http://heart.cochrane.org/resources-review-authors.

Follmann D, Elliot P, Suh I, Cutler J. Variance imputation for overviews of clinical trials with continuous response. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:769–73.

Hersen M, Hilsenroth MJ, Segal DL. Comprehensive handbook of psychological assessment. Hoboken: Wiley; 2004.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–34.

Brown MA, Munford AM, Munford PR. Behavior therapy of psychological distress in patients after myocardial infarction or coronary bypass. J Cardpulm Rehabil. 1993;13(3):201–10.

Burgess AW, Lerner DJ, d’ Agostino RB, Vokonas PS. A randomized control trial of cardiac rehabilitation. Soc Sci Med. 1987;24(4):359–70.

Cowan MJ, Pike KC, Kogan BH. Psychosocial nursing therapy following sudden cardiac arrest: impact on two-year survival. Nurs Res. 2001;50(2):68–76.

Elderen-van-Kemenade T, Maes S, van-den Broek Y. Effects of a health education programme with telephone follow-up during cardiac rehabilitation. Br J Clin Psychol. 1994;33(3):367–78.

Gallacher JEJ, Hopkinson CA, Bennett P, Burr ML, Elwood PC. Effect of stress management on angina. Psychol Heal. 1997;12(4):523–32.

HofmanBang C, Lisspers J, Nordlander R, et al. Two-year results of a controlled study of residential rehabilitation for patients treated with percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty—a randomized study of a multifactorial programme. Eur Hear J. 1999;20(20):1465–74.

Ibrahim MA, Feldman JG, Sultz HA, et al. Management after myocardial infarction: a controlled trial of the effect of group psychotherapy. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1974;5(3):253–68.

Jones DA, West RR. Psychological rehabilitation after myocardial infarction: multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1996;313(7071):1517–21.

Oldenburg B, Perkins RJ, Andrews G. Controlled trial of psychological intervention in myocardial infarction. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53(6):852–9.

Rahe RH, Ward HW, Hayes V. Brief group therapy in myocardial infarction rehabilitation: three- to four-year follow-up of a controlled trial. Psychosom Med. 1979;51(3):229–42.

Friedman M, Thoresen CE, Gill JJ, et al. Feasibility of altering type A behaviour pattern after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1982;66(1):83–92.

Stern MJ, Gorman PA, Kaslow L. The group counseling v exercise therapy study. A controlled intervention with subjects following myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143(9):1719–25.

Van-Dixhoorn JJ, Duivenvoorden HJ. Effect of relaxation therapy on cardiac events after myocardial infarction: a 5-year follow-up study. J Cardpulm Rehabil. 1999;19(3):178–85.

Appels A, Bar F, van der Pol G, et al. Effects of treating exhaustion in angioplasty patients on new coronary events: results of the randomized exhaustion intervention trial (EXIT). Psychosom Med. 2005;67(2):217–23.

Claesson M, Birgander L, Lindahl B, et al. Women’s hearts: stress management for women with ischemic heart disease: explanatory analyses of a randomized controlled trial. J Cardpulm Rehabil. 2005;25(2):93–102.

Koertge J, Janszky I, Sundin O, et al. Effects of a stress management program on vital exhaustion and depression in women with coronary heart disease: a randomized controlled intervention study. J Intern Med. 2008;263(3):281–93.

Mayou R, Thompson D, Clements A, et al. Guideline-based early rehabilitation after myocardial infarction: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(2):89–95.

McLaughlin T, Aupont O, Bambauer K, et al. Improving psychologic adjustment to chronic illness in cardiac patients: the role of depression and anxiety. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(12):1084–90.

Michalsen A, Grossman P, Lehmann N, et al. Psychological and quality-of-life outcomes from a comprehensive stress reduction and lifestyle program in patients with coronary artery disease: results of a randomized trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2005;74(6):344–52.

Peng J, Jiang LJ. Psychotherapy on negative emotions for the incidence of ischemia-related events in patients with coronary heart disease. Chin J Clin Rehabil. 2005;9(4):38–9.

Sebregts EHWJ, Falger PRJ, Appels A, Kester ADM, Bär FWHM. Psychological effects of a short behavior modification program in patients with acute myocardial infarction or coronary artery bypass grafting: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychosom Res. 2005;58(5):417–24.

Dunn AL, Trivedi MH, Kampert JB, Clark CG, Chambliss HO. Exercise treatment for depression: efficacy and dose response. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(1):1–8.

Kuper H, Nicholson A, Kivimaki M, et al. Evaluating the causal relevance of diverse risk markers: horizontal systematic review. BMJ. 2009;339:b4265.

Carney RM, Freedland KE, Miller GE, Jaffe AS. Depression as a risk factor for cardiac mortality and morbidity: a review of potential mechanisms. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:897–902.

Jacobson NS, Dobson KS, Truax PA, et al. A component analysis of cognitive—behavioral treatment for depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64(2):295–304.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge all the authors who provided additional information on request and Cornelia Junghans for Russian and German translations. Ben Whalley was supported by an ESRC fellowship (PTA-026-27-2113). We also wish to acknowledge the authors of the original Cochrane review as follows: Karen Rees, Division of Health Sciences, Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK; Philippa Davies, Academic Unit of Psychiatry, School of Social and Community Medicine, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK; Paul Bennett, Department of Psychology, University of Swansea, Swansea, UK; Shah Ebrahim, Department of Non-communicable Disease Epidemiology, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK; Zulian Liu, Peninsula Medical School, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK; Robert West, Wales Heart Research Institute, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK; and Tiffany Moxham, Wimberly Library, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, Florida, USA. The study was funded by a UK National Institute for Health Research Cochrane Programme Grant (CPG510).

Conflict of Interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

A version of this article has been accepted and published by the Cochrane Review Group, December 2011 [citation, Whalley B, Rees K, Davies P, Bennett P, Ebrahim S, Liu Z, West R, Moxham T, Thompson DR, Taylor RS. Psychological interventions for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011;8(art no CD002902). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002902.pub3].

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Whalley, B., Thompson, D.R. & Taylor, R.S. Psychological Interventions for Coronary Heart Disease: Cochrane Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Int.J. Behav. Med. 21, 109–121 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-012-9282-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-012-9282-x