Abstract

Purpose

Preoperative fitness training has been listed as a top ten research priority in anesthesia. We aimed to capture the current practice patterns and perspectives of anesthetists and colorectal surgeons in Australia and New Zealand regarding preoperative risk stratification and prehabilitation to provide a basis for implementation research.

Methods

During 2016, we separately surveyed fellows of the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA) and members of the Colorectal Society of Surgeons in Australia and New Zealand (CSSANZ). Our outcome measures investigated the responders’ demographics, practice patterns, and perspectives. Practice patterns examined preoperative assessment and prehabilitation utilizing exercise, hematinic, and nutrition optimization.

Results

We received 155 responses from anesthetists and 71 responses from colorectal surgeons. We found that both specialty groups recognized that functional capacity was linked to postoperative outcome; however, fewer agreed that robust evidence exists for prehabilitation. Prehabilitation in routine practice remains low, with significant potential for expansion. The majority of anesthetists do not believe their patients are adequately risk stratified before surgery, and most of their colorectal colleagues are amenable to delaying surgery for at least an additional two weeks. Two-thirds of anesthetists did not use cardiopulmonary exercise testing as they lacked access. Hematinic and nutritional assessment and optimization is less frequently performed by anesthetists compared with their colorectal colleagues.

Conclusions

An unrecognized potential window for prehabilitation exists in the two to four weeks following cancer diagnosis. Early referral, larger multi-centre studies focusing on long-term outcomes, and further implementation research are required.

Résumé

Objectif

Le conditionnement physique préopératoire a été cité dans les dix priorités de recherche les plus importantes en anesthésie. Notre objectif était de déterminer quels étaient les habitudes actuelles de pratique ainsi que les perspectives des anesthésistes et des chirurgiens colorectaux en Australie et en Nouvelle-Zélande concernant la stratification préopératoire du risque et la préhabilitation afin de proposer un point de départ pour la recherche sur sa mise en œuvre.

Méthode

Au cours de l’année 2016, nous avons soumis un questionnaire séparé aux membres du Collège australien et néozélandais des anesthésistes (ANZCA - Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists) et aux membres de la Société colorectale des chirurgiens australiens et néozélandais (CSSANZ - Colorectal Society of Surgeons in Australia and New Zealand). Nos critères d’évaluation portaient sur les données démographiques, les habitudes de pratique et les perspectives des répondants. Les questions sur les habitudes de pratique touchaient à l’évaluation préopératoire et la préhabilitation fondée sur l’exercice physique et l’optimisation antianémique et nutritionnelle.

Résultats

Nous avons reçu 155 réponses d’anesthésistes et 71 réponses de chirurgiens colorectaux. Notre questionnaire a révélé que les deux spécialités reconnaissaient que la capacité fonctionnelle est liée au pronostic postopératoire; toutefois, moins de répondants étaient d’avis qu’il existe des données probantes fiables concernant la préhabilitation. Dans la pratique de routine, la préhabilitation demeure peu courante mais a le potentiel de prendre plus d’ampleur. La plupart des anesthésistes estiment que leurs patients ne sont pas stratifiés adéquatement en fonction de leur risque avant leur chirurgie, et la plupart de leurs collègues colorectaux sont ouverts à l’idée de retarder la chirurgie d’au moins deux semaines supplémentaires. Deux tiers des anesthésiologistes n’ont pas eu recours à un test d’effort cardiopulmonaire par manque d’accès à ce type d’examen. L’évaluation et l’optimisation antianémique et nutritionnelle sont moins fréquemment réalisées par les anesthésistes comparativement à leurs collègues colorectaux.

Conclusion

Il existe une fenêtre potentielle mais non reconnue pour la mise en œuvre d’une préhabilitation au cours des deux à quatre semaines suivant l’annonce d’un diagnostic de cancer. Une prise en charge précoce par des spécialistes, des études multicentriques plus importantes s’intéressant aux pronostics à long terme et des travaux de recherche supplémentaires sur la mise en œuvre sont nécessaires.

Similar content being viewed by others

It is estimated that by 2030, cancer treatment will involve 45 million surgical procedures per year worldwide.1 Despite a relatively low incidence of anesthesia-related mortality, perioperative morbidity following major cancer surgery remains a significant contributor to healthcare expenditure.2,3 The aging and increasingly sedentary population in high-income countries including Canada, Australia, and the United States, along with its burgeoning comorbid burden,4 is likely to increase postoperative complication rates and length of hospital stay. The cost of all complications from patients undergoing rectal cancer resections in Australia during 2013 to 2014 totaled $77 million at an average of $28,000 per episode, with over half of patients likely to suffer from complications and be twice as costly. The frequency of complications for patients undergoing intra-abdominal surgery in Canada is also high, at 51.9%, with the occurrence of any complications tripling the cost on average.5,6 The increasing demand on the value-proposition of healthcare has increased interest in prehabilitation and over the past decade has seen a shift in focus by anesthetists to assume the role of perioperative physicians, particularly in the preoperative setting.7

Prehabilitation of the surgical patient refers to the preoperative optimization of functional capacity prior to an anticipated stressor—major cancer surgery—and typically occurs between diagnosis and elective surgical intervention.8 Optimization of patients with malignant disease conveys an extra set of challenges because of the functional decline associated with neoadjuvant therapy9 as well as the time-sensitive nature of the planned surgical intervention. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy per se also offers a window of opportunity, during which time preoperative optimization can occur in anticipation of major surgery.

Randomized-controlled studies have shown that unimodal approaches to prehabilitation can reduce postoperative complications by up to 50%.10,11,12 There has also been emerging research in prehabilitation, for multimodal programs involving exercise, nutrition, smoking cessation, and psychologic support.13,14 Nevertheless, it is unclear if this interest has translated into the clinical domain. This evidence-to-practice gap in healthcare is typically 17 years15; implementation science in the field of perioperative care is only an emerging field. With this survey we have attempted to gain insights into commonly studied implementation outcomes (acceptability, appropriateness, adoption, feasibility, penetration) by surveying attitudes of key stakeholders (surgeons and anesthetists). To date, there has only been one prior survey of North American colorectal surgeons, and none of anesthetists or any other perioperative clinicians.16 Our surveys set out to capture the perspectives and practice patterns among Australasian anesthetists and colorectal surgeons with regards to multimodal prehabilitation programs in major cancer surgery.

Methods

We conducted a survey of fellows of the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA) and members of the Colorectal Surgical Society of Australia and New Zealand (CSSANZ) to identify the uptake, perspectives, and practice patterns regarding objective risk assessment and prehabilitation in patients scheduled to undergo major cancer surgery.

Permission to survey ANZCA fellows was granted by the ANZCA Clinical Trials Network (CTN), and CSSANZ members by the CSSANZ secretariat following ethics approval from the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre Ethics Committee, Melbourne, Australia (LNR/16/PMCC/97). An e-mail containing a link to both surveys was distributed via the respective societies in 2016; the ANZCA survey of 17 questions was sent to 1,000 practicing fellows using simple random sampling, as per standard ANZCA CTN policy (as detailed in Appendices 1 and 2), while the CSSANZ survey of 33 questions was sent to all 207 practicing members. We aimed to capture as many ANZCA-affiliated anesthetists as possible (from a total of 5,310). A formal sample size calculation suggested that 131 ANZCA fellows were needed to allow an error margin of 8% for their responses, assuming the target population was 1,000 using a 95% confidence interval-based estimate.

The survey questions were sequentially generated and reduced by a multidisciplinary team led by anesthetists and colorectal surgeons, and included a hematologist, exercise physiologist, physiotherapist, nutritionist, and social worker. Both surveys were divided into several domains investigating the responders’ demographics, practice patterns, and perspectives, with the aim to generate at least two items within these domains using face and content validity. Practice patterns examined preoperative assessment and prehabilitation utilizing exercise, hematinic, and nutrition optimization. Questions examining practices and perspectives were designed as a five-Likert scale, with options such as not available, unsure, or other, and the option to comment where feasible. Excluding demographic questions, a total of 37 questions was reduced to 11 in the ANZCA survey; 31 questions was reduced to 27 in the CSSANZ survey.

The surveys were vetted by the respective societies and then piloted among four anesthetists and three colorectal surgeons respectively in our institution. Adjustments were continuously made based on feedback prior to online distribution. Surveys were administered using SurveyMonkey (Palo Alto, CA, USA). The electronic survey included logic which allowed further questioning based on responses to primary questions.

Duplicate responses were avoided. Allocation was blinded, IP addresses were not logged, and all responses remained anonymous. All participants received an e-mail reminder two weeks following the initial e-mail distribution date. Non-participation was assumed if no response was seen one month following the second e-mail. When measuring the proportion of responses to a survey item, the number of respondents to each survey was used for consistency purposes.

Result

The number of respondents included 155 of 1,000 anesthetists and 71 of 207 colorectal surgeons, with over 50% of each group graduating after the year 2000. On a weekly basis, 70% (50/71) of responding colorectal surgeons performed two to five major colorectal resections, whereas 77% (119/155) of the responding anesthetists cared for less than two patients undergoing major cancer surgery (Table). The surveys showed that the preoperative team is still dominated by the surgeon and anesthetist, with frequent consultation of organ-specific physicians such as cardiologists and respiratory physicians. Non-medical staff, such as dieticians, physiotherapists, and smoking cessation representatives, were either reported as unsure, never, or rarely involved in more than 59% of cases (42/71 and 106/155) (Fig. 1). The American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification was the most common tool used for risk stratification by anesthetists and colorectal surgeons (Fig. 2).

Incidence of preoperative clinician involvement by specialty. This graph shows anesthetists and surgeons reporting that other clinicians, particularly allied health, are infrequently involved in the primary preoperative care of patients undergoing major cancer surgery. A = anesthetist; CS = colorectal surgeon

Incidence of type of risk assessment scores utilized in clinical practice. This graph shows that the ASA is used most frequently, with most other risk assessments infrequently used. A = anesthetists, ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification; CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index; CS = colorectal surgeons; ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncologic Group score; HAQ = Hospital-specific Health Assessment Questionnaire; NSQIP = American College of Surgeons’ National Surgery Quality Improvement Program; POSSUM = Physiologic and Operative Severity Score for the enumeration of mortality and morbidity

Preoperative assessment of risk and evaluation of functional capacity (fitness)

Both anesthetists and colorectal surgeons rarely used objective measurements of fitness (Fig. 3). Less than 10% of anesthetists (9/155) and colorectal surgeons (6/71) routinely utilize cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET). Nevertheless, 46% (33/71) of colorectal surgeons believe CPET to be useful, and 40% (62/155) of anesthetists believe there is robust evidence for objective functional testing in major cancer surgery. Two-thirds (93/155) of surveyed anesthetists lack access to a CPET laboratory. Reasons for non-use for the remaining 21 respondents included time and logistical problems, requesting, interpreting, or acting upon the results (16/21), or a lack of knowledge of the test itself (3/21).

Preoperative evaluation of hematinic and nutritional status

Anemia is frequently assessed by the preoperative anesthetist (131/155) and colorectal surgeon (70/71); however, while almost all colorectal surgeons screen for iron deficiency, 39% (28/71) would perform the test in the absence of anemia. Conversely, 20% (31/155) of anesthetists never screen for it even in the presence of a hemoglobin of less than 100 g·L−1. When iron deficiency anemia is identified, colorectal surgeons (64/71 vs 36/71) are more likely to treat it with iron infusion than with oral therapy compared with anesthetists (99/155 vs 91/155) (Fig. 4).

Predominance of strategies used for the preoperative treatment of iron deficiency anemia. This graph shows the comparative predominance of each intervention between anesthetists and colorectal surgeons. Colorectal surgeons have a greater preference to treat iron deficiency anemia with intravenous iron infusion. A = anesthetists; CS = colorectal surgeons; EPO = erythropoietin; Intraop = intraoperative; PRBC = packed red blood cells; Preop = preoperativef

Formal nutrition assessment scores are not utilized by the anesthetist (less than 9/155) or colorectal surgeon (less than 10/71). Subjective assessment or knowledge of the body mass index (BMI) may lead half the surveyed colorectal surgeons to consult a dietician (48/71). Anesthetists (34/155) mostly do not consult dieticians even if malnutrition is found.

Biomarkers to assess for general function and nutrition such as albumin and blood sugar level are used by colorectal surgeons (55/71 and 47/71), but somewhat less by anesthetists (104/155 and 94/155) (Fig. 5).

Incidence of use of biomarkers for preoperative risk assessment. This figure shows that albumin is most frequently used to assess nutrition. BSL is also used frequently. Colorectal surgeons are more likely to also use pre-albumin than anesthetists are. A = anesthetists; BNP = brain natriuretic peptide; BSL = blood sugar level; CRP = C-reactive protein, CS = colorectal surgeons; HbA1c = glycated hemoglobin

Perspectives regarding prehabilitation

There is uniform agreement between anesthetists (125/155) and colorectal surgeons (64/71) that functional capacity affects postoperative outcomes. Nevertheless, more than two-thirds of both groups have mixed opinions on the strength of evidence for prehabilitation (12/71 and 47/155). Colorectal surgeons feel that they would see benefit from prehabilitation programs (65%, 46/71), while just half of anesthetists believe that both their patients (70/155) and their surgical colleagues (73/155) would expect benefit from such programs.

The current implementation of prehabilitation programs remains low in the practices of colorectal surgeons and anesthetists, with the potential for expansion in their institutions (Fig. 6). In patients not receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy, 69% (49/71) of colorectal surgeons would be prepared to delay surgery for at least two additional weeks. This figure increases to 79% (56/71) in patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Anesthetists do not believe their patients are routinely risk stratified (58/155), though they are unlikely to believe their patients would benefit from a delay in surgery (12/155).

Perceptions regarding utility and deliverability of objective functional assessment and prehabilitation programs. This figure shows that there is widespread belief that physical reserve is correlated with postoperative outcome, but that the practical application of this is impeded by a need for more evidence. A = anesthetist; CS = colorectal surgeons

Discussion

Prior evidence has shown that reductions in functional capacity are correlated with an increase in postoperative complications.17,18 Our results broadly indicate that while anesthetists are regularly involved in preoperative assessment, structured risk assessment and objective functional assessment of patients scheduled for major cancer surgery remain less frequently used. Moreover, key components of a prehabilitation program, especially nutritional assessment, are poorly understood and integrated into clinical practice.

There is a difference in perception of benefit among the two groups, which may act as a barrier to implementing effective preoperative care. More colorectal surgeons see benefit in prehabilitation; however, anesthetists perceive that fewer surgeons view prehabilitation to be of benefit. This is further reinforced by the fact that a larger proportion of colorectal surgeons responded than anesthetists. Differences in response rates and quality of responses between anesthetists and colorectal surgeons in this regard may be a result of different focus among craft groups, with most responding colorectal surgeons having a greater oncologic focus, whereas anesthetists were surveyed from a general base, with oncologic surgery constituting only part of their practice. The strongest evidence base for objective risk assessment and prehabilitation has been in intracavity surgery,19,20 whereas our definition of major surgery may also include other oncologic surgery, such as head and neck surgery or breast surgery. More evidence is required to determine whether prehabilitation should include these surgical specialties.

Prehabilitation can only be performed in the window period between cancer diagnosis and definitive surgery. The perception of how much time is available differs between groups. The timing of anesthetist preoperative assessment in Australian practice is highly variable and is institution-, surgeon-, and patient-dependent. Time to scheduled date of surgery can range from days to weeks and is affected by the use of neoadjuvant therapy. While more than half of responding anesthetists believed that patients were not adequately risk stratified, far fewer believed that patients would benefit from postponing surgery on occasion. It is unclear why this is the case but may be a result of timing of the assessment. Ultimately, this is a conservative approach compared with the colorectal perspective, where, despite the need for timely surgical intervention for colorectal cancer patients, most of the respondents were prepared to delay elective surgery. This was particularly true for advanced rectal cancer cases where neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy is firmly integrated into the care pathway. Neoadjuvant therapy, while being a major contributor to a reduction in functional capacity, provides a window in which to risk-stratify, discuss the appropriateness of delaying surgery, and provide prehabilitation. Therefore, a significant potential exists for a period of preoperative assessment and management by an extended multidisciplinary team. Early referral is required to maximize this window period for effective prehabilitation.

The general anesthetist contributes significantly to perioperative care for patients undergoing major cancer surgery, given that three-quarters of the surveyed cohort care for less than two such patients per week. It is likely that this would be reflected, if not further emphasized, among non-respondents. As the care of oncologic major surgery crosses multiple anesthesia subspecialties, most anesthetists are likely to provide the bulk of perioperative care to patients undergoing such surgery at some point in their careers. Further education should therefore be targeted at all anesthetists, rather than just at those with a special interest in oncoanesthesia or geriatric anesthesia.

In current practice, the recognition and integration of any allied health profession in the preoperative setting is rare. Both colorectal surgeons and anesthetists rarely assess and manage malnutrition; while a dietician may be involved in cases where it has been subjectively identified, this does not appear to be routine.

Exercise assessment and prehabilitation

While both groups agree that functional capacity is associated with outcomes, and that it can be reduced with cancer therapy, they are hesitant to believe that current methods of assessment and treatment can improve outcomes.9 The CPET is a dynamic, symptom-limited, non-invasive test that provides objective analysis of the functional integration of the cardiovascular, pulmonary, hematinic, and cellular metabolic systems.21 The CPET has been increasingly used in the perioperative setting over the last decade22 and is considered the gold standard test of functional capacity.23 The utility for CPET has been established preoperatively in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer as a marker for morbidity and mortality24,25,26,27 and has been incorporated into international guidelines.28 Its use for major intra-abdominal surgery has been increasingly studied. While studies have shown that CPET may have a role in risk stratification for esophageal, urological, pancreatic, hepatic, and colorectal cancers, a 2016 systematic review by Moran et al. identified the need for further research in certain areas—particularly in areas of colorectal and upper gastrointestinal surgeries, with a lack of consensus regarding variables and definitions of such outcomes by CPET.19 The recently published METS trial covering major non-cardiac surgery has confirmed the value of peak oxygen uptake measured by CPET in predicting non-cardiac complications after surgery. An important finding of this study was the lack of credibility of subjective assessments of cardiac risk in predicting outcomes.29 Further, other variables such as the minute ventilation to carbon dioxide expiratory ratio, heart rate response, and CPET kinetics during the recovery phase have shown promise but have yet to be examined in a large cohort.19,30,31 In addition, the effect of physiologic reserve on return to intended oncologic therapy has also been examined,32,33 and may be a useful outcome to measure in future studies examining the role of CPET in major cancer surgery.

Our surveys suggest that both craft groups infrequently use objective risk assessments of functional capacity either because of perceived insufficient evidence or a lack of access to resource-intensive tests such as CPET. The Duke Activity Status Index (DASI) has previously shown modest correlation with peak oxygen uptake in patients undergoing intra-abdominal surgery for cancer.34,35 The METS trial showed that the DASI can predict postoperative outcomes in a heterogenous cohort undergoing major surgery.29 Other alternatives to CPET, such as the six-minute walk test, do exist and are infrequently used despite their relative simplicity. This may be in part be due to a lack of evidence in cancer-specific cohorts and lack of high-grade validated studies comparing these tests with the gold standard of CPET or postoperative outcomes.36

Preoperative exercise within a prehabilitation program can rapidly improve functional capacity before surgery, and is well-placed to combat the deconditioning suffered as a result of sedentary lifestyle and neoadjuvant chemotherapy.9,37 While preoperative exercise improves postoperative outcomes in lung cancer patients,38 its role in improving postoperative outcomes in major abdominal cancer surgery has yet to be elucidated. Randomized-controlled trials have shown that preoperative exercise in major abdominal cancer surgery improves functional outcomes, but none have been adequately powered to examine the effect of preoperative exercise on postoperative complications, and none have examined the effect of preoperative exercise on postoperative mortality.20,39

Nutrition assessment and prehabilitation

As reflected in our survey results, nutrition in the preoperative phase is unfamiliar among anesthetists and some colorectal surgeons. The BMI is almost exclusively used by responding anesthetists and colorectal surgeons, along with comparing acute weight loss and actual body weight with ideal body weight, to identify increased nutritional risk. Nevertheless, a 2011 systematic review by Gupta et al. showed that in head and neck, gastrointestinal, thoracic, and gynecologic cancers, BMI has no association with perioperative morbidity and mortality.40 While others have shown evidence in predicting postoperative outcomes, a consensus as to the utility of any particular tool has yet to be formed.41

Nutritional prehabilitation is another emerging field in cancer patients. Promising pilot studies have shown a benefit in preoperative functional capacity after whey supplementation or immunonutrition; but, like other prehabilitation studies, these pilot projects require validation in larger randomized-controlled studies.42,43,44 The importance of nutrition and postoperative outcomes should be reinforced by perioperative specialists, particularly anesthetists, when identifying at-risk patients and proactively involving dietetics.

Hematinic assessment and treatment

Despite being readily accessible on the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, anesthetists appear inclined to treat preoperative iron deficiency anemia with oral rather than intravenous iron infusion. While further adequately powered randomized-controlled trials are needed to show the effect of preoperative iron infusion on postoperative outcomes, and therefore cost-benefit, studies have shown symptomatic improvement within days and a rise in hemoglobin within one to two weeks.45,46 Symptomatic benefit has also translated to patients with non-anemic iron deficiency.47

Risk assessment

The American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status (ASA-PS) score has been regularly used in clinical anesthesia, as well as for research, reimbursement, and resource allocation,48 and this is reflected in our surveys. Studies have shown correlations between the ASA-PS in postoperative outcomes such as infection, anastomotic failure, pulmonary complications, length of stay, and mortality. In a range of surgical cohorts including orthopedic, gastrointestinal, gynecologic, and thoracic,48,50,51,52,53,54,55 the ASA score is simple and can be performed rapidly at the bedside, but it carries significant inter-rater variation and is therefore thought to lack discriminatory power56 compared with more complex but informative risk scores.57

Approaches to preoperative assessment

Anesthetists are more likely to perform a cardiorespiratory assessment whereas colorectal surgeons are likely to examine the patient more globally, as shown by a relative increased focus on anemia and nutrition assessment. Anemia and blood transfusions are related to cancer recurrence, and malnutrition is associated with infection and anastomotic leak, but colorectal surgeons will also consider other functions, including independent stoma management, and quality of life factors such as postoperative incontinence.57,59,60 This reflects two different perspectives towards cancer care, which is likely to be improved with increased multidisciplinary involvement from allied health practitioners.

Future directions

Our surveys suggest that preoperative risk assessment of functional capacity in the preoperative period is relatively rapid and brief. Nevertheless, responding colorectal surgeons have indicated their willingness to delay surgery for an extra two to four weeks, suggesting that access and evidence are the two limiting factors in translating the knowledge into practice. A 2015 joint task force of combined professional anesthesia organizations, consumers, and other stakeholders ranked the impact of prehabilitation with exercise as a top ten research priority in perioperative medicine.61 Despite promising research into prehabilitation programs, the evidence base largely consists of small, single-centre studies, and has yet to examine meaningful outcomes such as morbidity and mortality. Recent research into multimodal programs has examined a variety of combinations of different interventions, including physical fitness, nutrition, hematinic, smoking and alcohol cessation, and psychologic interventions, but an ideal combination of interventions has yet to be determined.14 The overall use of prehabilitation is low and there is not enough evidence for a change in practice to occur. These barriers and opportunities identified may serve as a basis for implementation of science studies in the perioperative literature. Nevertheless, our survey suggests a willingness among stakeholders to participate in the high quality research that will be needed to improve the uptake of prehabilitation into mainstream practice.

Current limitations in undertaking research to build the existing evidence base include a lack of pre-existing infrastructure, a lack of access to objective risk assessment, and poor capacity for preoperative exercise training programs. This is compounded by limited preoperative utilization of physiotherapists, exercise physiologists, and dieticians. A potential space exists for multidisciplinary clinical and research engagement in the two to four-week preoperative period, which will build the evidence base.

Limitations

The major limitation of this study is the low survey response rate, particularly among anesthetists. As such, our data are susceptible to selection bias and are neither adequately powered to detect differences between subgroups or subspecialties nor draw definitive conclusions beyond the general overview in cancer surgery that has been presented here. The response rate may have been so low because non-respondents are not interested in perioperative medicine in cancer surgery—a relatively new field—or more specifically, in prehabilitation. Fellows that graduated after the year 2000 had the highest representation in our respondents, which may support this notion. As this study was performed on Australian and New Zealand organizations, its applicability to transnational cohorts may be limited. Nevertheless, our findings may be of relevance to countries with similar cultures in anesthesia, particularly with similar training procedures, case-mix, and burden of disease, such as Canada.62

Conclusion

Our survey shows that Australian anesthetists and surgeons are willing to participate in high quality prehabilitation research. Currently, allied health expertise is lacking, risk assessment of functional capacity is inconsistently used, and the uptake of prehabilitation is low. Anesthetists in particular have a stronger cardiorespiratory focus, whereas colorectal surgeons are likely to consider hematinic and nutritional status, although iron deficiency is underdiagnosed and undertreated. The involvement of allied health staff in the preoperative period could potentially improve risk assessment, particularly regarding nutrition, and allow for early triage of preoperative and postoperative interventions. Institutions should consider redesigning processes and improving infrastructure to ensure early multidisciplinary referral to improve risk stratification, while allowing research into prehabilitation programs. The significant potential for expansion of prehabilitation programs as high value and low cost interventions is dependent on the effectiveness of these interventions being confirmed by adequately powered, multi-centre randomized-controlled trials in the future.

References

Sullivan R, Alatise OI, Anderson BO, et al. Global cancer surgery: delivering safe, affordable, and timely cancer surgery. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16: 1193-224.

Bainbridge D, Martin J, Arango M, Cheng D; Evidence-based Peri-operative Clinical Outcomes Research (EPiCOR) Group. Perioperative and anaesthetic-related mortality in developed and developing countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2012; 380: 1075-81.

Nathan H, Atoria CL, Bach PB, Elkin EB. Hospital volume, complications, and cost of cancer surgery in the elderly. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 107-14.

Findlay GP, Goodwin AP, Protopapa K, Smith NC, Mason M. Knowing the risk: a review of the peri-operative care of surgical patients. London: National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death; 2011.

Independent Hospital Pricing Authority. National Hospital Cost Data Collection - Australian Public Hospitals Cost Report 2013-2014, Round 18. Canberra: Department of Health; 2016.

Bailey JG, Davis PJ, Levy AR, Molinari M, Johnson PM. The impact of adverse events on health care costs for older adults undergoing nonelective abdominal surgery. Can J Surg 2016; 59: 172-9.

Grocott MP, Pearse RM. Perioperative medicine: the future of anaesthesia? Br J Anaesth 2012; 108: 723-6.

Silver JK, Baima J. Cancer prehabilitation: an opportunity to decrease treatment-related morbidity, increase cancer treatment options, and improve physical and psychological health outcomes. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2013; 92: 715-27.

West MA, Loughney L, Barben CP, et al. The effects of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy on physical fitness and morbidity in rectal cancer surgery patients. Eur J Surg Oncol 2014; 40: 1421-8.

Barberan-Garcia A, Ubre M, Roca J, et al. Personalised prehabilitation in high-risk patients undergoing elective major abdominal surgery: a randomized blinded controlled trial. Ann Surg 2018; 267: 50-6.

Boden I, Skinner EH, Browning L, et al. Preoperative physiotherapy for the prevention of respiratory complications after upper abdominal surgery: pragmatic, double blinded, multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2018; 360: j5916.

Barakat HM, Shahin Y, Khan JA, McCollum PT, Chetter IC. Preoperative supervised exercise improves outcomes after elective abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 2016; 264: 47-53.

Carli F, Gillis C, Scheede-Bergdahl C. Promoting a culture of prehabilitation for the surgical cancer patient. Acta Oncologica 2017; 56: 128-33.

Bolshinsky V, Li MH, Ismail H, Burbury K, Riedel B, Heriot A. Multimodal prehabilitation programs as a bundle of care in gastrointestinal cancer surgery: a systematic review. Dis Colon Rectum 2018; 61: 124-38.

Lane-Fall MB, Cobb BT, Cene CW, Beidas RS. Implementation science in perioperative care. Anesthesiol Clin 2018; 36: 1-15.

Boereboom CL, Williams JP, Leighton P, Lund JN; Exercise Prehabilitation in Colorectal Cancer Delphi Study Group. Forming a consensus opinion on exercise prehabilitation in elderly colorectal cancer patients: a Delphi study. Tech Coloproctol 2015; 19: 347-54.

Nagamatsu Y, Shima I, Yamana H, Fujita H, Shirouzu K, Ishitake T. Preoperative evaluation of cardiopulmonary reserve with the use of expired gas analysis during exercise testing in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2001; 121: 1064-8.

West MA, Parry MG, Lythgoe D, et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing for the prediction of morbidity risk after rectal cancer surgery. Br J Surg 2014; 101: 1166-72.

Moran J, Wilson F, Guinan E, McCormick P, Hussey J, Moriarty J. Role of cardiopulmonary exercise testing as a risk-assessment method in patients undergoing intra-abdominal surgery: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth 2016; 116: 177-91.

Singh F, Newton RU, Galvao DA, Spry N, Baker MK. A systematic review of pre-surgical exercise intervention studies with cancer patients. Surg Oncol 2013; 22: 92-104.

Older P, Hall A, Hader R. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing as a screening test for perioperative management of major surgery in the elderly. Chest 1999; 116: 355-62.

Levett DZ, Grocott MP. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing, prehabilitation, and Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS). Can J Anesth 2015; 62: 131-42.

Guazzi M, Adams V, Conraads V, et al. EACPR/AHA Joint Scientific Statement. Clinical recommendations for cardiopulmonary exercise testing data assessment in specific patient populations. Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 2917–27.

Smith TP, Kinasewitz GT, Tucker WY, Spillers WP, George RB. Exercise capacity as a predictor of post-thoracotomy morbidity. Am Rev Respir Dis 1984; 129: 730-4.

Bechard D, Wetstein L. Assessment of exercise oxygen consumption as preoperative criterion for lung resection. Ann Thorac Surg 1987; 44: 344-9.

Win T, Jackson A, Sharples L, et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise tests and lung cancer surgical outcome. Chest 2005; 127: 1159-65.

Bolliger CT, Wyser C, Roser H, Soler M, Perruchoud AP. Lung scanning and exercise testing for the prediction of postoperative performance in lung resection candidates at increased risk for complications. Chest 1995; 108: 341-8.

Brunelli A, Kim AW, Berger KI, Addrizzo-Harris DJ. Physiologic evaluation of the patient with lung cancer being considered for resectional surgery: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2013; 143(5 Suppl): e166S-90S.

Wijeysundera DN, Pearse RM, Shulman MA, et al. Assessment of functional capacity before major non-cardiac surgery: an international, prospective cohort study. Lancet 2018; 391: 2631-40.

Hightower CE, Riedel BJ, Feig BW, et al. A pilot study evaluating predictors of postoperative outcomes after major abdominal surgery: physiological capacity compared with the ASA physical status classification system. Br J Anaesth 2010; 104: 465-71.

Ha D, Choi H, Zell K, et al. Association of impaired heart rate recovery with cardiopulmonary complications after lung cancer resection surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2015; 149(1168–73): e3.

Chandrabalan VV, McMillan DC, Carter R, et al. Pre-operative cardiopulmonary exercise testing predicts adverse post-operative events and non-progression to adjuvant therapy after major pancreatic surgery. HPB (Oxford) 2013; 15: 899-907.

Aloia TA, Zimmitti G, Conrad C, Gottumukalla V, Kopetz S, Vauthey JN. Return to intended oncologic treatment (RIOT): a novel metric for evaluating the quality of oncosurgical therapy for malignancy. J Surg Oncol 2014; 110: 107-14.

Struthers R, Erasmus P, Holmes K, Warman P, Collingwood A, Sneyd JR. Assessing fitness for surgery: a comparison of questionnaire, incremental shuttle walk, and cardiopulmonary exercise testing in general surgical patients. Br J Anaesth 2008; 101: 774-80.

Li MH, Bolshinsky V, Ismail H, Ho KM, Heriot A, Riedel B. Comparison of Duke Activity Status Index with cardiopulmonary exercise testing in cancer patients. J Anesth 2018; 32: 576-84.

Santos BF, Souza HC, Miranda AP, Cipriano FG, Gastaldi AC. Performance in the 6-minute walk test and postoperative pulmonary complications in pulmonary surgery: an observational study. Braz J Phys Ther 2016; 20: 66-72.

West MA, Loughney L, Lythgoe D, et al. Effect of prehabilitation on objectively measured physical fitness after neoadjuvant treatment in preoperative rectal cancer patients: a blinded interventional pilot study. Br J Anaesth 2015; 114: 244-51.

Sebio Garcia R, Yáñez Brage MI, Giménez Moolhuyzen E, Granger CL, Denehy L. Functional and postoperative outcomes after preoperative exercise training in patients with lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Interactive Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2016; 23: 486-97.

Boereboom C, Doleman B, Lund JN, Williams JP. Systematic review of pre-operative exercise in colorectal cancer patients. Tech Coloproctol 2016; 20: 81-9.

Gupta D, Vashi PG, Lammersfeld CA, Braun DP. Role of nutritional status in predicting the length of stay in cancer: a systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Ann Nutr Metab 2011; 59: 96-106.

McClave SA, Kozar R, Martindale RG, et al. Summary points and consensus recommendations from the North American Surgical Nutrition Summit. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2013; 37(5 Suppl): 99S-105S.

Li C, Carli F, Lee L, et al. Impact of a trimodal prehabilitation program on functional recovery after colorectal cancer surgery: a pilot study. Surg Endosc 2013; 27: 1072-82.

Marik PE, Zaloga GP. Immunonutrition in high-risk surgical patients: a systematic review and analysis of the literature. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2010; 34: 378-86.

Gillis C, Loiselle SE, Fiore JF Jr, et al. Prehabilitation with whey protein supplementation on perioperative functional exercise capacity in patients undergoing colorectal resection for cancer: a pilot double-blinded randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Acad Nutr Diet 2016; 116: 802-12.

Ng O, Keeler B, Mishra A, et al. Iron therapy for pre-operative anaemia (protocol). The Cochrane Collaboration - 2015. Available from URL: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011588/epdf/full (accessed December 2018).

Koduru P, Abraham BP. The role of ferric carboxymaltose in the treatment of iron deficiency anemia in patients with gastrointestinal disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2016; 9: 76-85.

Okonko DO, Grzeslo A, Witkowski T, et al. Effect of intravenous iron sucrose on exercise tolerance in anemic and nonanemic patients with symptomatic chronic heart failure and iron deficiency FERRIC-HF: a randomized, controlled, observer-blinded trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 51: 103-12.

Daabiss M. American Society of Anaesthesiologists physical status classification. Indian J Anaesth 2011; 55: 111-5.

Wolters U, Wolf T, Stutzer H, Schroder T. ASA classification and perioperative variables as predictors of postoperative outcome. Br J Anaesth 1996; 77: 217-22.

Ridgeway S, Wilson J, Charlet A, Kafatos G, Pearson A, Coello R. Infection of the surgical site after arthroplasty of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2005; 87: 844-50.

Tang R, Chen HH, Wang YL, et al. Risk factors for surgical site infection after elective resection of the colon and rectum: a single-center prospective study of 2,809 consecutive patients. Ann Surg 2001; 234: 181-9.

Rauh MA, Krackow KA. In-hospital deaths following elective total joint arthroplasty. Orthopedics 2004; 27: 407-11.

Sauvanet A, Mariette C, Thomas P, et al. Mortality and morbidity after resection for adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction: predictive factors. J Am Coll Surg 2005; 201: 253-62.

Prause G, Offner A, Ratzenhofer-Komenda B, Vicenzi M, Smolle J, Smolle-Juttner F. Comparison of two preoperative indices to predict perioperative mortality in non-cardiac thoracic surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1997; 11: 670-5.

Carey MS, Victory R, Stitt L, Tsang N. Factors that influence length of stay for in-patient gynaecology surgery: is the Case Mix Group (CMG) or type of procedure more important? J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2006; 28: 149-55.

Aronson WL, McAuliffe MS, Miller K. Variability in the American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification Scale. AANA J 2003; 71: 265-74.

Bilimoria KY, Liu Y, Paruch JL, et al. Development and evaluation of the universal ACS NSQIP surgical risk calculator: a decision aide and informed consent tool for patients and surgeons. J Am Coll Surg 2013; 217: 833-42.e1-3.

Cata JP, Wang H, Gottumukkala V, Reuben J, Sessler DI. Inflammatory response, immunosuppression, and cancer recurrence after perioperative blood transfusions. Br J Anaesth 2013; 110: 690-701.

Bernard AC, Davenport DL, Chang PK, Vaughan TB, Zwischenberger JB. Intraoperative transfusion of 1 U to 2 U packed red blood cells is associated with increased 30-day mortality, surgical-site infection, pneumonia, and sepsis in general surgery patients. J Am Coll Surg 2009; 208: 931-7, 7.e1-2; discussion 938-9.

Kwag SJ, Kim JG, Kang WK, Lee JK, Oh ST. The nutritional risk is a independent factor for postoperative morbidity in surgery for colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Treat Res 2014; 86: 206-11.

Boney O, Bell M, Bell N, et al. Identifying research priorities in anaesthesia and perioperative care: final report of the joint National Institute of Academic Anaesthesia/James Lind Alliance Research Priority Setting Partnership. BMJ Open 2015; 5: e010006.

Canadian Medical Association. Anesthesiology Profile: Canadian Medical Association; 2014. Available from URL: https://www.cma.ca/Assets/assets-library/document/en/advocacy/Anesthesiology-e.pdf (accessed December 2018).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the ANZCA CTN and the CSSANZ secretariat for vetting and facilitating the survey’s distribution. We also acknowledge Prof Linda Denehy, A/Prof Prue Cormie, Mr Satish Warrier, Ms Belinda Steer, and Ms Fiona Wiseman for feedback regarding the surveys. Dr Ho would like to thank WA Health and Raine Medical Research Foundation for their support through the Raine Clinical Research Fellowship.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Ho is funded by WA Health and Raine Medical Research Foundation through the Raine Clinical Research Fellowship. The funding agencies have no influence on the choice of the subject matter, design of the study, data analyses, the decision to publish the results, and the final content of the manuscript. The other authors have not received any funding.

Author contributions

Michael H.-G. Li and Vladimir Bolshinsky contributed substantially to all aspects of this manuscript, including conception and design; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, and drafting the article. Kate Burbury, Hilmy Ismail, Alexander Heriot, and Bernhard Riedel contributed substantially to the conception and design of the manuscript, and drafting the article. Babak Amin contributed substantially to the analysis of data and drafting of the article. Kwok M. Ho contributed substantially to the analysis of data, interpretation of data, and drafting the article.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Gregory L. Bryson, Deputy Editor-in-Chief, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1 Survey questions sent to ANZCA fellows

Question | Potential response |

|---|---|

I have read the description of the study, acknowledge that I am currently practicing anesthesia, and volunteer my participation in the research project | Yes |

No | |

Please indicate your country and state/territory of practice | Australia – ACT, NSW, NT, QLD, SA, TAS, VIC, WA |

New Zealand | |

Other (please specify) | |

When did you complete anesthetic training? | 2010 or later |

2000–2009 | |

1990–1999 | |

1980–1990 | |

Prior to 1979 | |

Other (please specify) | |

What is the nature of your principal place of practice? | Predominantly public |

Predominantly private | |

Equal mix of public and private | |

How many patients scheduled for major cancer surgery would be under your perioperative care on a weekly basis? | Rarely |

Less than two per week | |

2–5 per week | |

More than six per week | |

Please describe the proportion of patients you see per week who are undergoing major cancer surgery that are: | Deconditioned |

Adequately risk stratified in the preoperative process | |

Never, rarely, sometimes, often, always | Likely to have benefited from postponing surgery to achieve improved optimization (functional capacity, hematinics, nutrition …etc.) for surgery |

Which of the following surgical risk scoring systems do you use in the preoperative assessment of patients under your care that are scheduled for major cancer surgery? | ASA |

Charlson Comorbidity Index | |

Never, rarely, sometimes, often, always | POSSUM scoring system |

ACS NSQIP | |

ECOG performance status | |

Hospital-Specific Health Assessment Questionnaire | |

Which of the following specialists are primarily involved in the preoperative assessment of patients under your care scheduled for major cancer surgery? | Preoperative anesthetist |

Perioperative physician (internal medicine) Cardiologist | |

Never, rarely, sometimes, often, always, not available | Respiratory physician |

Hematologist | |

Geriatrician | |

Intensive care physician (preoperatively) | |

Dietician | |

Physiotherapist | |

Exercise physiologist/kinesiologist | |

QUIT Smoking Program representative (for a known smoker) | |

Social worker (e.g., advanced care planning, discharge planning) | |

Which of the following objective assessments of functional capacity do you use for major cancer surgery? | Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET/CPX) |

Witnessed stair climb test | |

Never, rarely, sometimes, often, always, not available | Six-minute walk test (6MWT) |

Incremental shuttle test | |

Structured frailty assessment (e.g., TUG test, sit to stand test, Edmonton frailty score) | |

Do you have access to cardiopulmonary exercise testing? | No |

Yes, and I use it | |

Yes, but I do not use it (please comment) | |

Given that you use cardiopulmonary exercise testing, do you use it for the following in patients undergoing major cancer surgery? | Risk stratification |

Inform patients of risk | |

Never, rarely, sometimes, often, always | Inform and guide prehabilitation programs |

Influence operative decision-making (e.g., seek alternate surgery or non-surgical technique) | |

Inform shared decision-marking and advanced care | |

Other (please specify) | |

Do you assess patients undergoing major cancer surgery for the following: | Anemia Iron deficiency at Hb > 130 g·L−1 |

Never, rarely, sometimes, often, always | Iron deficiency at Hb < 130 g·L−1 |

Iron deficiency at Hb < 100 g·L−1 | |

B12/folate deficiency | |

Renal function | |

Erythropoeitin levels | |

Other (please specify) | |

Which of the following are done preoperatively to treat a patient with iron deficiency anemia who is undergoing major cancer surgery? | Oral iron supplementation |

Iron infusion | |

Transfusion of blood products preoperatively | |

Never, rarely, sometimes, often, always, not available | Transfusion of blood products at time of surgery |

EPO injection | |

Other (please specify) | |

If you identify malnutrition in patients scheduled for major cancer surgery, do you refer to dietetics? | Never, rarely, sometimes, often, always, not available |

Which of the following assessment tools do you use? | BMI (body mass index) |

MST (malnutrition screening tool) | |

Never, rarely, sometimes, often, always, unsure | MUST (malnutrition universal screening tool) |

MNA (mini nutritional assessment) | |

MNA-SF (mini nutritional assessment short form) | |

SGA (subjective global assessment) | |

PG-SGA (patient-generated subjective global assessment) | |

Other (please specify) | |

As part of the preoperative assessment, how often are the following biochemical markers evaluated for colorectal cancer patients in your institution? | Albumin |

Pre-albumin/transthyretin | |

Not available, never, rarely, sometimes, often, always | C-reactive protein (CRP) |

Blood sugar level (BSL) | |

Glycated hemoglobin (HBA1C) | |

Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) | |

Other (please specify) | |

The following questions relate to your attitudes towards prehabilitation: | Regularly exercising patients suffer less postoperative complications compared with sedentary patients. |

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy reduces physical reserve. | |

Strongly disagree, disagree, unsure, agree, strongly agree | Objective risk assessment of functional capacity is supported by robust evidence. |

Benefit from prehabilitation programs are already supported by robust evidence. | |

Prehabilitation programs are potentially deliverable in my institution. | |

Prehabilitation programs are already implemented in my institution. | |

My surgeons would see benefit from prehabilitation. | |

My patients would be receptive to participating in prehabilition programs. | |

Prehabilition programs are an area that I would like to participate or develop in my practice setting. |

Appendix 2 Survey questions sent to CSSANZ members

Question | Potential response |

|---|---|

How many major colorectal resection do you perform per week? | Rarely |

Less than two per week | |

2–5 per week | |

6–10 per week | |

Which statement best describes your colorectal practice? | Public hospital |

Private hospital | |

Both public hospital and private practice; other | |

When did you complete colorectal training? | 2010 or later |

2000–2009 | |

1990–1999 | |

1980–1990 | |

Prior to 1979 | |

Other | |

Which of the following surgical risk scoring systems are used in the preoperative assessment of colorectal cancer patients under your care? | ASA |

Never, rarely, sometimes, often, always | Charlson Comorbidity Index |

CR-POSSUM scoring system | |

ACS NSQIP | |

ECOG performance status | |

Hospital-Specific Health Assessment Questionnaire | |

Which of the following medical specialists are primarily involved in the preoperative assessment of colorectal cancer patients under your care? | Perioperative physician |

Not available, never, rarely, sometimes, often, always | Cardiologist |

Anesthetist | |

Intensive care physician | |

Respiratory physician | |

Hematologist | |

Geriatrician | |

Which of the following allied health specialists are involved in the preoperative assessment of colorectal cancer patients under your care? | Dietician |

Not available, never, rarely, sometimes, often, always | Physiotherapist |

Kinesiologist/exercise physiologist | |

Quit smoking program representative | |

In your institution, how often are the following factors addressed in the preoperative work up of colorectal cancer patients? | Smoking and alcohol cessation |

Not available, never, rarely, sometimes, often, always | Anxiety and depression |

Advanced care planning | |

Do you assess elective colorectal cancer patients preoperatively for malnutrition? | Yes |

No | |

Other (specify) | |

Which of the following assessment tools do you use? | BMI |

Not available, never, rarely, sometimes, often, always | MNA |

MNA-SF | |

SGA | |

PG-SGA | |

MUST | |

Subjectively, if you identify malnutrition, do you refer to dietetics? | Yes |

No | |

Other (specify) | |

As part of the preoperative assessment, how often are the following biochemical markers evaluated for colorectal cancer patients in your institution? | Albumin |

Not available, never, rarely, sometimes, often, always | Pre-albumin/transthyretin |

CRP | |

BSL | |

HBA1C | |

Do you perform a preoperative fitness assessment for elective colorectal cancer patients? | Yes |

No | |

Other (specify) | |

Which of the following objective assessment tools do you use? | CPET/CPX |

Not available, never, rarely, sometimes, often, always | 6MWT |

2MWT | |

Shuttle test | |

Do you believe that physically fit patients who exercise regularly suffer less postoperative complications compared with unfit, sedentary patients? | Yes |

No | |

Uncertain | |

Do you think that neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy will reduce physiologic reserve/fitness? | Yes |

No | |

Uncertain | |

By what amount will neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy reduce physiologic reserve/fitness?(anaerobic threshold is an estimator of the onset of metabolic acidosis during exercise) | Mild (< 10% of anaerobic threshold) |

Moderate (10–20% of anaerobic threshold) | |

Severe (> 20% of anaerobic threshold) | |

Do you think cardiopulmonary exercise testing is useful for colorectal cancer patients? | Yes |

No | |

Uncertain | |

Do you use cardiopulmonary exercise testing for the following? | Risk stratification |

Not available, never, rarely, sometimes, often, always | Inform patient of risk |

Inform and guide prehabilitation programs | |

Operative decision-making | |

Do you assess colorectal cancer patients for anemia? | Yes |

No | |

Other (specify) | |

Do you assess colorectal cancer patients for iron deficiency | Routinely |

Never | |

Only if anemic | |

Other (please specify) | |

In your institution, which of the following are done preoperatively to a patient with iron deficiency anemia? (can select more than one answer) | Oral iron supplementation |

Iron infusion | |

Transfusion of blood products preoperatively | |

Transfusion of blood products at time of surgery | |

EPO injection | |

Uncertain | |

Other (please specify) | |

Do you think prehabilitation programs are applicable to cancer surgery | Yes |

No | |

Uncertain | |

Please indicate the degree of importance of prehabilitation programs for colorectal cancer patients in the following scenarios: rate: 1 (low importance) – 10 (high importance) | Patients with low rectal cancers |

Patients undergoing NACRT | |

Patients > 75 yr | |

Patients that require an open resection | |

Deconditioned patients awaiting definitive surgery, Patients with comorbid disease (ASA ≥ III) | |

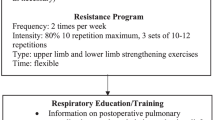

Please indicate the degree of importance of the following parameters in colorectal cancer surgery prehabilitation programs: rate: 1 (low importance) – 10 (high importance) | Cardiorespiratory optimization through aerobic exercise training |

Musculoskeletal optimization through strength training | |

Respiratory optimization through incentive spirometry | |

Psychologic assessment and optimization | |

Balance and gait assessment and optimization | |

Smoking and alcohol cessation | |

Nutritional assessment and optimization (including obesity and malnutrition) | |

Patient blood management (diagnosis and optimization of anemia and/or iron deficiency) | |

What is your optimal time interval to perform an ultralow anterior resection (ULAR) following neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy? | < 6 weeks |

6–8 weeks | |

8–10 weeks | |

10–12 weeks | |

> 12 weeks | |

Other (please specify) | |

In a patient with colorectal cancer NOT receiving neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, how long would you be willing to delay surgery to implement prehabilitation? | < additional 2 weeks |

additional 2–4 weeks | |

additional 4–6 weeks | |

> additional 6 weeks | |

other (please specify) | |

For how long would you be willing to delay an elective resection in a patient with colorectal cancer to improve their preoperative status? | < 2 weeks |

2–4 weeks | |

4–6 weeks | |

> 6 weeks | |

I refuse to delay surgery in this setting | |

Not applicable | |

Other (please speficy) | |

Cancer prehabilitation programs are (yes, no, uncertain): | Already supported by robust evidence of their benefit |

Already implemented in my institution | |

Potentially deliverable in my institution | |

Not of use for my patients as I do not believe in their benefit | |

An emerging field and I would like to participate in this area of research | |

What do you think is the potential benefit of prehabilitation for these interventions? (no benefit, little benefit, moderate benefit, significant benefit, essential) | Open colectomy |

Laparoscopic/robotic assisted colectomy | |

Open ULAR | |

Laparoscopic/Robotic ULAR | |

Open APR | |

Laparoscopic/robotic APR |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, M.HG., Bolshinsky, V., Ismail, H. et al. A cross-sectional survey of Australian anesthetists’ and surgeons’ perceptions of preoperative risk stratification and prehabilitation. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 66, 388–405 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-019-01297-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-019-01297-9