Abstract

Purpose

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a common complication of critical illness. Sex- or gender-based analyses are rarely conducted and their effect on outcomes is unknown. We assessed for an effect modification of thromboprophylaxis (dalteparin or unfractionated heparin [UFH]) by sex on thrombotic (deep venous thrombosis [DVT], pulmonary embolism [PE], VTE) and mortality outcomes in a secondary analysis of the Prophylaxis for Thromboembolism in Critical Care Trial (PROTECT).

Methods

We conducted unadjusted analyses using Cox proportional hazards analysis, stratified by centre and admission diagnostic category, including sex, treatment, and an interaction term. Additionally, we performed adjusted analyses and assessed the credibility of our findings.

Results

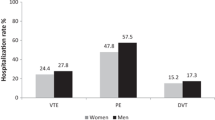

Critically ill female (n = 1,614) and male (n = 2,113) participants experienced similar rates of DVT, proximal DVT, PE, any VTE, ICU death, and hospital death. In unadjusted analyses, we did not find significant differences in treatment effect favouring males (vs females) treated with dalteparin (vs UFH) for proximal leg DVT, any DVT, or any PE, but found a statistically significant effect (moderate certainty) favouring dalteparin in males for any VTE (males: hazard ratio [HR], 0.71; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.52 to 0.96 vs females: HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.81 to 1.68; P = 0.04). This effect remained after adjustment for baseline characteristics (males: HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.52 to 0.96 vs females: HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 0.81 to 1.68; P = 0.04) and weight (males: HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.52 to 0.96 vs females: HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.83 to 1.73; P = 0.03). We did not identify a significant effect modification by sex on mortality.

Conclusions

We found an effect modification by sex of thromboprophylaxis on VTE in critically ill patients that requires confirmation. Our findings highlight the need for sex- and gender-based analyses in acute care research.

Résumé

Objectif

La maladie thromboembolique veineuse (MTEV) est une complication fréquente au cours des maladies critiques. Des analyses basées sur le sexe ou le genre sont rarement effectuées et leur effet sur les critères d’évaluation est inconnu. Nous avons évalué une modification de l’effet de la thromboprophylaxie (daltéparine ou héparine non fractionnée [HNF]) selon le sexe sur la maladie thrombotique (thrombose veineuse profonde [TVP], embolie pulmonaire [EP], MTEV) et sur les critères de mortalité au cours d’une analyse secondaire de l’étude PROTECT (essai de prophylaxie de la thromboembolie en soins critiques).

Méthode

Nous avons réalisé des analyses non ajustées au moyen d’une analyse des risques proportionnels de Cox, stratifiées par site et catégorie diagnostique à l’admission, incluant le sexe, le traitement et un terme d’interaction. Nous avons aussi réalisé des analyses ajustées et avons évalué la crédibilité de nos constatations.

Résultats

Les participant·es dans un état critique de sexe féminin (n = 1 614) et masculin (n = 2 113) ont présenté des taux semblables de TVP, EP, et MTEV de tout type, de décès en soins intensifs et de décès en milieu hospitalier. Nous n’avons pas trouvé de différences significatives dans les analyses non ajustées en faveur des hommes (par rapport aux femmes) traités par la daltéparine (par rapport à l’HNF) pour la TVP de la cuisse, la TVP de tout type, ou tout type d’EP; en revanche, nous avons trouvé un effet statistiquement significatif (certitude modérée) en faveur de la daltéparine pour la MTEV de tout type (hommes : rapport de risque [RR], 0,71; intervalle de confiance [IC] à 95 %, 0,52 à 0,96 par rapport aux femmes : RR, 1,16; IC 95 %, 0,81 à 1,68; P = 0,04). Cet effet a persisté après ajustement pour les caractéristiques à l’inclusion (hommes : RR, 0,70; IC 95 %, 0,52 à 0,96 par rapport aux femmes : RR, 1,17; IC 95 %, 0,81 à 1,68; P = 0,04) et le poids (hommes : RR, 0,70; IC 95 %, 0,52 à 0,96 par rapport aux femmes : RR, 1,20; IC 95 %, 0,83 à 1,73; P = 0,03). Nous n’avons pas identifié de modification significative de l’effet en fonction du sexe sur la mortalité.

Conclusion

Nous avons trouvé une modification de l’effet en fonction du sexe sur la thromboprophylaxie sur la MTEV chez les patient·es en état critique; cette constatation nécessite une confirmation. Nos constatations soulignent le besoin d’analyses en fonction du sexe et du genre dans la recherche sur les soins aigus.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Moser KM, LeMoine JR, Nachtwey FJ, Spragg RG. Deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Frequency in a respiratory intensive care unit. JAMA 1981; 246: 1422–4.

PROTECT Investigators for the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group and the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group, Cook D, Meade M, et al. Dalteparin versus unfractionated heparin in critically ill patients. New Engl J Med 2011: 364: 1305–14. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1014475

Geerts W, Cook D, Selby R, Etchells E. Venous thromboembolism and its prevention in critical care. J Crit Care 2002; 17: 95–104. https://doi.org/10.1053/jcrc.2002.33941

Cook DJ, Donadini MP. Pulmonary embolism in medical-surgical critically ill patients. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2010; 24: 677–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hoc.2010.05.002

Kahn SR, Lim W, Dunn AS, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2012; 141: e195S–e226S. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.11-2296

Schünemann H, Cushman M, Burnett AE, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prophylaxis for hospitalized and nonhospitalized medical patients. Blood Adv 2018; 2: 3198–225. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2018022954

Al Yami MS, Silva MA, Donovan JL, Kanaan AO. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in medically ill patients: a mixed treatment comparison meta-analysis. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2018; 45: 36–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-017-1562-5

Park J, Lee JM, Lee JS, Cho YJ. Pharmacological and mechanical thromboprophylaxis in critically ill patients: a network meta-analysis of 12 trials. J Korean Med Sci 2016; 31: 1828–37. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2016.31.11.1828

Coen S, Banister E (Eds.). What a Difference Sex and Gender Make: A Gender, Sex and Health Research Casebook. Ottawa: Canadian Institutes of Health Research; 2012.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research. How to integrate sex and gender into research. Available from URL: http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/50836.html (accessed July 2022).

Kim ESH, Menon V. Status of women in cardiovascular clinical trials. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2009; 29: 279–83. https://doi.org/10.1161/atvbaha.108.179796

Greenspan JD, Craft RM, LeResche L, et al. Studying sex and gender differences in pain and analgesia: a consensus report. Pain 2007; 132: S26–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2007.10.014

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Risk of next-morning impairment after use of insomnia drugs; FDA requires lower recommended doses for certain drugs containing zolpidem (Ambien, Ambien CR, Edluar, and Zolpimist), 2013. Available from URL: https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/Drug-Safety-Communication--Risk-of-next-morning-impairment-after-use-of-insomnia-drugs--FDA-requires-lower-recommended-doses-for-certain-drugs-containing-zolpidem-%28Ambien--Ambien-CR--Edluar--and-Zolpimist%29.pdf (accessed July 2022).

U.S. Government Accountability Office. Drug safety: most drugs withdrawn in recent years had greater health risks for women, 2001. Available from URL: http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-01-286R (accessed July 2022).

Heidari S, Babor TF, De Castro P, Tort S, Curno M. Sex and gender equity in research: rationale for the SAGER guidelines and recommended use. Res Integr Peer Rev 2016; 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-016-0007-6

Cook D, Meade M, Guyatt G, et al. PROphylaxis for thromboembolism in critical care trial protocol and analysis plan. J Crit Care 2011; 26: e1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2011.02.010

Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med 1985; 13: 818–29.

Schandelmaier S, Briel M, Varadhan R, et al. Development of the instrument to assess the credibility of effect modification analyses (ICEMAN) in randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses. CMAJ 2020; 192: E901–6.

Yoshikawa Y, Yamashita Y, Morimoto T, et al. Sex differences in clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with venous thromboembolism. Circ J 2019; 83: 1581–9. https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.cj-19-0229

Scheres LJ, Brekelmans MP, Beenen LFM, Büller HRB, Cannegieter SC, Middeldorp S. Sex-specific differences in the presenting location of a first venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost 2017; 15: 1344–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.13712

White RH, Zhou H, Murin S, Harvey D. Effect of ethnicity and gender on the incidence of venous thromboembolism in a diverse population in California in 1996. Thromb Haemost 2005; 93: 298–305. https://doi.org/10.1160/th04-08-0506

Tormene D, Ferri V, Carraro S, Simioni P. Gender and the risk of venous thromboembolism. Semin Thromb Hemost 2011; 37: 193–8. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1273083

Roach RE, Lijfering WM, Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC, le Cessie S. Sex difference in risk of second but not of first venous thrombosis: paradox explained. Circulation 2014; 129: 51–6. 15. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.113.004768

Guistozzi M, Valerio L, Agnelli G, et al. Sex-specific differences in the presentation, clinical course, and quality of life of patients with acute venous thromboembolism according to baseline risk factors. Insights from the PREFER in VTE. Eur J of Intern Med 2021; 88: 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2021.03.014

McRae S, Tran H, Schulman S, Ginsberg J, Kearon C. Effect of patient’s sex on risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2006; 368: 371–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(06)69110-1

Trinchero A, Scheres LJ, Prochaska JH, et al. Sex-specific differences in the distal versus proximal presenting location of acute deep vein thrombosis. Thromb Res 2018; 172: 74–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2018.10.025

Rodger MA, Kahn SR, Wells PS, et al. Identifying unprovoked thromboembolism patients at low risk for recurrence who can discontinue anticoagulant therapy. CMAJ 2008: 179: 417–26. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.080493

Rodger MA, Le Gal G, Anderson DR, et al. Validating the HERDOO2 rule to guide treatment duration for women with unprovoked venous thrombosis: multinational prospective cohort management study. BMJ 2017; 356: j1065. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j1065

Marshall AL, Bartley AC, Ashrani AA, et al. Sex-based disparities in venous thromboembolism outcomes: a national inpatient sample (NIS)-based analysis. Vasc Med 2017; 22: 121–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1358863x17693103

Kyrle PA, Minar E, Bialonczyk C, Hirschl M, Weltermann A, Eichinger S. The risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism in men and women. N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 2558–63. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa032959

Baglin T, Luddington R, Brown K, Baglin C. High risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism in men. J Thromb Haemost 2004; 2: 2152–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.01050.x

Levine MN, Hirsh J, Gent M, et al. Optimal duration of anticoagulant therapy: a randomized trial comparing four weeks with three months of warfarin in patients with proximal deep vein thrombosis. Thromb Haemost 1995; 74: 606–11.

Schulman S, Rhedin AS, Lindmarker P, et al. A comparison of six weeks with six months of oral anticoagulant therapy after a first episode of venous thromboembolism. Duration of Anticoagulation Trial Study Group. N Engl J Med 1995; 332: 1661–5. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199506223322501

Schulman S, Grangvist S, Holmström M, et al. The duration of oral anticoagulant therapy after a second episode of venous thromboembolism. The Duration of Anticoagulation Trial Study Group. N Engl J Med 1997; 336: 393–8. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199702063360601

Ridker PM, Goldhaber SZ, Danielson E, et al. Long-term, low-intensity warfarin therapy for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 1425–34. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa035029

Kearon C, Gent M, Hirsh J, et al. A comparison of three months of anticoagulation with extended anticoagulation after a first episode of idiopathic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 901–7. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199903253401201

Schulman S, Wåhlander K, Lundström T, Clason SB, Eriksson H, THRIVE III Investigators. Secondary prevention of venous thromboembolism with the oral direct thrombin inhibitor ximelagatran. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 1713–21. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa030104

Cohen M, Demers C, Gurfinkel EP, et al. A comparison of low-molecular-weight heparin with unfractionated heparin for unstable coronary artery disease. Efficacy and Safety of Subcutaneous Enoxaparin in Non-Q-Wave Coronary Events Study Group. N Engl J Med 1997; 337: 447–52. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199708143370702

Roberts R, Rogers WJ, Mueller HS, et al. Immediate versus deferred beta-blockade following thrombolytic therapy in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Results of the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) II-B study. Circulation 1991; 83: 422–37. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.83.2.422

Antman EM, Cohen M, Radley D, et al. Assessment of the treatment effect of enoxaparin for unstable angina/non–Q-wave myocardial infarction: TIMI 11B-ESSENCE meta-analysis. Circulation 1999; 100: 1602–8. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.100.15.1602

Fragmin during Instability in Coronary Artery Disease (FRISC) Study Group. Low-molecular-weight heparin during instability in coronary artery disease. Lancet 1996; 347: 561–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(96)91270-2

Antman EM, Morrow DA, McCabe CH, et al. Enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin with fibrinolysis for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 1477–88. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa060898

Mega JL, Morrow DA, Ostör E, et al. Outcomes and optimal antithrombotic therapy in women undergoing fibrinolysis for ST-elevation myocardial. Circulation 2007; 115: 2822–28. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.106.679548

Rogers WJ, Baim DS, Gore JM, et al. Comparison of immediate invasive, delayed invasive, and conservative strategies after tissue-type plasminogen activator. Results of the thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) Phase II-A trial. Circulation 1990; 81: 1457–76. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.81.5.1457

Becker RC Spencer F, Gibson M, et al. Influence of patient characteristics and renal function on factor Xa inhibition pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics after enoxaparin administration in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J 2002; 143: 753–9. https://doi.org/10.1067/mhj.2002.120774

Tamargo J, Rosano G, Walther T, et al. Gender differences in the effects of cardiovascular drugs. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother 2017; 3: 163–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjcvp/pvw042

Campbell NR, Hull RD, Brant R, Hogan DB, Pineo GF, Raskob GE. Different effects of heparin in males and females. Clin Invest Med 1998; 21: 71–8.

Jick H, Slone D, Borda I, Shapiro S. Efficacy and toxicity of heparin in relation to age and sex. N Engl J Med 1968; 279: 284–6. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm196808082790603

National Institutes of Health. Sex and gender. Available from URL: http://orwh.od.nih.gov/research/sex-gender (accessed July 2022).

Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Meet the methods series: methods for prospectively and retrospectively incorporating gender-related variables in clinical research. Available from URL: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/52608.html (accessed July 2022).

Clayton JA, Tannenbaum C. Reporting sex, gender, or both in clinical research? JAMA 2016; 316: 1863–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.16405

Prins MH, Smits KM, Smits LJ. Methodologic ramifications of paying attention to sex and gender differences in clinical research. Gend Med 2007, 4: S106–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1550-8579(07)80051-9

Johnson JL, Greaves L, Repta R. Better science with sex and gender: facilitating the use of a sex and gender-based analysis in health research. Int J Equity Health 2009; 8: 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-8-14

Author contributions

Karen E. A. Burns, Diane Heels-Ansdell, and Deborah J. Cook contributed to study design. Diane Heels-Ansdell and Lehana Thabane contributed to data analysis and presentation. All authors contributed to data interpretation and manuscript preparation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the patient and families who provided consent to participate in PROTECT. In addition, we would like to thank Dr. Aimee J. Sarti for her review of our manuscript for the Grants and Manuscripts Committee of the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. We also wish to acknowledge the investigators and research coordinators around the world who participated in this trial. PROTECT was supported by the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group and the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group. The list of PROTECT collaborators is provided in the Data Online Supplement to the original trial report (2).

Disclosures

Mark A. Crowther declares that in the last 24 months he has provided educational materials and/or presented on behalf Bayer, Pfizer, and CSL Behring, and he has served in an advisory capacity to Hemostasis Reference Laboratories and Syneos Health. The other authors declare that they have no financial or nonfinancial conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding statement

This study was not funded. The original PROTECT trial was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Australian and New Zealand College of Anesthetists Research Foundation. Prophylactic dalteparin was provided by Pfizer Inc. and Esai Co., Ltd. None of these agencies played a role in the design, conduct, analysis, interpretation, or write-up of the original trial or this study. K. Burns was supported in this work by the Physician Services Incorporated of Ontario Mid-Career Research Award. D. Cook and S. Kahn were supported by Tier-1 Research Chairs from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. M. Crowther was supported by the Leo Chair in Thrombosis of McMaster University. S. Kahn is an investigator of the CanVECTOR Network, which holds grant funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Funding Reference: CDT142654) and from the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé (File # 309911).

Data availability statement

The data will be made available upon written request to Drs Cook and Burns.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Stephan K. W. Schwarz, Editor-in-Chief, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/ Journal canadien d’anesthésie.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Members of the study group PROTECT Investigators, the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group, and the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group are placed in Acknowledgement section.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Burns, K.E.A., Heels-Ansdell, D., Thabane, L. et al. Sex differences in thromboprophylaxis of the critically ill: a secondary analysis of a randomized trial. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 70, 1008–1018 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-023-02457-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-023-02457-8