Abstract

Employees in the disability sector are subject to a range of stressors in the work place, and it is important that employers provide stress-management interventions to optimize coping and psychological wellbeing of these staff. The purpose of this preliminary study was to evaluate the impact of a group-based training program, known as ‘Occupational Mindfulness’ (OM), on employee coping and wellbeing within a disability service in Australia. The study involved a longitudinal observational design. Thirty-four participants (22 managers and 12 disability support workers, aged 23 to 60 years) completed a range of mindfulness and psychological wellbeing measures prior to commencement of the OM training program and immediately following completion of the program. The program was positively evaluated by participants and found to be associated with significant increases in positive affect and the mindfulness facet of observing. In contrast, extrinsic job satisfaction decreased significantly from baseline to post-training, while negative affect, perceived stress, anxiety and negative emotional symptoms increased significantly. Depressive state, intrinsic job satisfaction, general job satisfaction, satisfaction with life, burnout, compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, compassion for others, self compassion and the four mindfulness facets of describing, acting with awareness, non-judging of inner experience and non-reactivity to inner experience did not change significantly from baseline to post-training. Participants reported enhanced awareness of signs and sources of stress, and positive changes in self-care attitudes and behaviours and interactions with clients and colleagues. Reasons for the seemingly paradoxical findings of highly favourable participant evaluation of the OM training program alongside increases in perceived stress, anxiety, negative emotional symptoms and negative affect and decreases in job satisfaction immediately following the program are discussed. Overall, the OM program yielded a range of benefits to participants and holds significant potential to be transferred to other work settings in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Like many other countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, work-related stress is widely prevalent in Australia and constitutes a growing challenge for employees, employers and the wider community (European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions 2007; LaMontagne et al. 2006. Work-related or occupational stress refers to the response that an individual may experience when confronted with job demands and pressures that are incommensurate with his or her knowledge and skills, and challenge his or her capacity to cope (World Health Organization 2010). It is well-established that chronic high levels of occupational stress can lead to a range of psychological, social and physical problems for affected individuals (Belkic et al. 2004; Bellavia and Frone 2005; Cohen et al. 2007; Dollard 2003; LaMontagne et al. 2006; Levi 2005; Tennant 2001). For example, prolonged workplace stress can eventually lead to burnout, particularly among staff in human service roles (Borritz et al. 2010). Maslach and Florian (1988) observed that manifestations of burnout include a sense of having no emotional resources left to offer others (emotional exhaustion), the development of a negative and callous attitude towards clients (depersonalization) and dissatisfaction with one's accomplishments in the workplace.

Beyond these human costs, workplace stress can adversely affect organizations through absenteeism, presenteeism, staff turnover, job performance, counter-productive work behaviours and compensation claims (Burton et al. 2005; Fox et al. 2001; Godin and Kittel 2004; LaMontagne et al. 2006; Musich et al. 2006). For example, annually in Australia, stress-related absenteeism and presenteeism have been estimated to directly cost employers $10.11 billion, while imposing a $14.81 billion burden on the Australian economy (Medibank Private Limited 2008).

Stressors reported by disability support workers have included work organization, role ambiguity, role conflict, workloads, colleagues, immediate management, insufficient resources, lack of staff support, limited decision latitude and feeling under-rewarded for work effort Koritsas et al. (2010). Apart from stressors common to many work settings, disability support workers who staff residential services for people with disabilities are also subject to a range of additional stressful factors in their roles, including verbal, physical and emotional abuse from clients (Jenkins et al. 1997; Mitchell and Hastings 2001; Strand et al. 2004). For example, Koritsas et al. (2010) reported that support workers' psychological wellbeing was negatively predicted by exposure to challenging behaviour. There is limited research on stress and psychological wellbeing among managers in the disability sector. In a number of studies, however, the wellbeing of residential house managers and disability support workers has been compared. For example, Rose et al. (2000) found that community house managers reported higher levels of stress, pressure and anxiety than the direct care workers employed in the houses. Key stressors for these managers included responsibility, interface between work and home life, and role clarity. In relation to stress among senior managers in the disability sector, there appears to be scant research. Research on stress among senior managers in other human services sectors such as health, however, has indicated that senior managers in these fields experience elevated levels of stress and anxiety compared to the general population (Caplan 1994; Hutchinson and Purcell 2010).

Elevated stress among disability sector employees has been associated with a range of adverse outcomes for these workers (Gray-Stanley et al. 2010). For example, in a sample of 323 direct support staff, work-related stress was associated with depressive symptoms (Gray-Stanley 2009). In addition to having a detrimental impact on staff themselves, elevated stress and decreased psychological wellbeing among disability support workers have been shown to have an adverse impact on client–staff interactions. For example, Thomas and Rose (2010) found that perceived general positive affect was related to the likelihood of reporting spending greater effort in helping the people they supported, while lack of reciprocity in the relationships staff had with the people they supported was related to perceived burnout. In addition, emotional exhaustion was found to be negatively correlated with positive interactions with clients among 79 direct care staff employed in services for people with intellectual disabilities (Lawson and O'Brien 1994).

Other research has demonstrated that workplace programs aimed at decreasing perceived stress and promoting mental health can be effective in reducing the deleterious effects of occupational stress on both individuals and the organizations by which they are employed (Giga et al. 2003; Klatt et al. 2009). Such programs are aimed at eliminating or modifying stressors and/or enhancing the capacity of workers to cope with stressors (LaMontagne et al. 2006). While it is important that organizations take responsibility for eliminating stressors where feasible, most work roles involve inherent sources of stress that are difficult or impossible to eliminate. For example, in a residential service setting, disability support staff work with clients who may present a range of challenging behaviours, the manifestation of which may be beyond the control of the support worker. In such situations where stressors cannot be controlled by individuals, it is important to employ stress-reduction strategies focused on the individual's response to the stressor, rather than attempts to control the stressor.

In the last decade or so, studies investigating mindfulness-based interventions for work-related stress have been found to be evaluated positively in the literature (e.g. Cohen-Katz et al. 2005; Davidson et al. 2003; Galantino et al. 2005; Shapiro et al. 2007). Mindfulness has been defined as moment-to-moment, non-reactive, non-judgmental awareness (Kabat-Zinn 1994). It involves deliberately bringing one's attention to the present experience in a non-reactive way. Although originating from Eastern meditation practices, mindfulness is not based on any particular belief system and is suitable for use in secular settings. Bishop et al. (2004) argued that mindfulness has two distinct components. The first of these pertains to self-regulation of attention such that it is focused on the present moment, enabling heightened awareness of mental events. The second component involves an orientation towards immediate experience that reflects curiosity, openness and acceptance (Bishop et al. 2004). Hofmann et al. (2010) suggested that an open and non-judgmental approach to present moment experience can ameliorate the impact of stressors by reducing orientation towards the past or future in attempting to deal with stressors, a maladaptive coping mechanism which is associated with reduced emotional wellbeing. In addition, mindfulness may lead to a reduction in the use of experiential avoidance strategies, which can be detrimental to mental health when used to avoid emotions, thoughts, memories and physical sensations (Hayes and Feldman 2004).

Mindfulness training has been shown to be effective in reducing stress and enhancing psychological wellbeing in a range of employees, including staff employed in human service roles. For example, in a sample of 12 nurses, significant decreases in emotional exhaustion were found immediately following completion of an 8-week mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) training program, compared to pre-intervention levels (Cohen-Katz et al. 2005). Furthermore, in the same study, pre- to post-MBSR improvements in levels of emotional exhaustion and personal accomplishment were significantly higher in the intervention group, compared to 13 nurses in a wait-list control group. In an uncontrolled study, Galantino et al. (2005) investigated the effectiveness of an 8-week intervention based on mindfulness meditation principles that also included elements from cognitive therapy and was adapted for a health care environment. Among 84 hospital employees who attended this program, there was a significant improvement from pre- to post-intervention in all assessed domains of mood (tension–anxiety, depression–dejection, anger–hostility, vigour–activity, fatigue–inertia and confusion–bewilderment) and emotional exhaustion (Galantino et al. 2005). As another example, in a randomized controlled trial involving a sample of 28 healthcare professionals, Shapiro et al. (2005) found that, compared to controls, participants who completed an 8-week MBSR training program reported a significantly greater reduction in perceived stress and a significantly higher increase in self-compassion. In addition, Mackenzie et al. (2006) conducted a randomized controlled trial to examine the impact of a brief 4-week mindfulness-based training program on wellbeing among 30 nurses and nurses aides employed at a long-term care geriatric hospital. In this study, compared to the control group, mindfulness training participants reported a significantly greater improvement in life satisfaction and general wellbeing from baseline to post-mindfulness training (Mackenzie et al. 2006). Shapiro et al. (2007) conducted a prospective non-randomised cohort-controlled study involving 22 caregivers who participated in an MBSR program and 32 who were assigned to a control group. Compared to participants in the control group, those in the MBSR group reported significantly higher declines in stress, negative affect, and state and trait anxiety, and significantly higher increases in mindfulness, positive affect and self-compassion. Although there is some variation in the formats of mindfulness-based interventions for stress, the literature indicates that those modelled on the 8-week MBSR group training program developed by Kabat-Zinn (1990) have been most widely studied.

In the past decade, a number of researchers have reported findings indicating that mindfulness training for disability support workers results in benefits for both staff and clients. For example, Noone and Hastings (2010) described a 1.5-day mindfulness-based training program undertaken by 34 support staff employed in residential services for adults with intellectual disabilities. They reported that despite no changes in workplace stressors (e.g. challenging client behaviours, lack of staff support and resources, bureaucracy and low status for staff), there was a significant pre- to post-training program improvement in staff psychological wellbeing as measured by the 12-item General Health Questionnaire.

In a study on the impact of teaching mindfulness techniques to staff supporting people with a disability, improvements in wellbeing for people with a disability were found (Singh et al. 2004). Singh et al. (2004) delivered mindfulness training to staff who supported three men who had profound intellectual and physical disabilities. Regardless of the level of ‘happiness’, men who spent their leisure time with one of the trained staff were rated as happier being with that staff member after the staff member had received mindfulness training than before the training.

Extrapolating from the literature on the influence of mindfulness training on wellbeing in human services workers, it might be expected that mindfulness training would also result in lowered perceived stress, negative affect, depressive symptoms, anxiety and burnout, and increased levels of mindfulness, positive affect, life satisfaction, compassion for others and self-compassion among employees in the disability sector. Accordingly, the Victorian State Government Office responsible for protection of the rights of people with a disability subject to restrictive interventions and compulsory treatment commissioned researchers from Monash University to design, implement and evaluate a highly structured mindfulness-based training program to decrease stress and improve psychological wellbeing and job satisfaction among support workers and managers employed in the disability sector. The overall aim of this study was to evaluate this training program, known as ‘Occupational Mindfulness’ (OM), as deployed within a leading non-government provider of disability services in the Australian state of Victoria. Based on previous research into similar mindfulness programs, it was hypothesised that participation in the OM training program would lead to an increase in participants' levels of mindfulness, positive affect, life satisfaction, job satisfaction, compassion for others and self-compassion. In addition, it was expected that participation in the OM training program would lead to a decrease in participants' levels of perceived stress, negative affect, depressive symptoms, anxiety, negative emotional symptoms and burnout.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited through a leading non-government provider of disability services, referred to in this paper as ‘the organization’. Inclusion criteria were regular employment at one of two homes in the community that provided supported residential services selected for the study, employment in a managerial role in the geographic areas associated with either of the participating residential service houses or having a senior managerial role at the organization's head office. Apart from developing personal mindfulness skills, the involvement of managers was regarded as important in order to support the development of an organizational culture of mindfulness, and for managers to understand what participation in the OM training program by support workers entailed. In addition, having the program authorized and attended by managers at the highest level of the organization was regarded as an important implementation issue in creating a culture where staff felt permitted to use mindfulness skills in their work roles.

All disability support staff regularly employed at two of the organization's residential services houses (group 1 and group 2) were invited to participate in this study. For group 1, 10 (nine disability support workers and the house manager) of 11 invited staff agreed to participate, yielding a response rate of 90.9 %. For group 2, six (five disability support workers and the house manager) of eight invited staff participated, a response rate of 75.0 %. Group 3 was comprised of 20 managers from 26 who were invited to participate, a response rate of 76.9 %. The overall response rate for all three groups was 80.0 %. The assignment of participants to separate groups for managers and staff employed at each of the houses was intended such that participants might feel less inhibited to engage fully in the training program. Two disability support workers from group 1 withdrew from the study following the first week of the OM training program, leaving a total of 34 participants. Questionnaires for the pre-training program time point (T1) were returned by 34 (100.0 %) participants, while 29 participants (85.3 %) returned the post-training program time point (T2) questionnaire. The mean age of participants was 42.9 (SD, 9.6) years. Other demographic details for the sample are displayed in Table 1.

Although the percentage of female managers (68.18 %) was higher than the percentage of female disability workers (41.67 %), this difference was not significant, χ 2(1, 34) = 2.25, p = .13. A Mann–Whitney test revealed that managers were significantly older (Mdn, 46.5 years) than disability support workers (Mdn, 36.0 years), U = 44.0, p < .01. The results of a Fisher's exact test indicated that managers were significantly more likely than disability support workers to have completed postgraduate tertiary studies, p < .01.

Measures

Prior to inclusion in the study, participants were screened for depression using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). The PHQ-9 includes nine questions about the frequency of nine core symptoms of depression. It has good internal reliability (α = .86–.89) (Kroenke et al. 2001), excellent test–retest reliability over a week (r (ICC) = .81–.96) (Löwe et al. 2004) and diagnostic validity for major depression (Kroenke et al. 2001). Participants were considered at risk of clinically significant depression if their responses to the PHQ-9 indicated suicidal ideation or experience of at least four symptoms of depression for more than half the days in the past fortnight, including at least one of the first two listed symptoms (little interest or pleasure in doing things; and feeling down, depressed or hopeless). In this study, the PHQ-9 was used as an aid to diagnosis in conjunction with the interviewer's clinical judgment.

Participants completed a range of self-administered measures prior to commencement (T1) and immediately following completion (T2) of the training program. The pre- and post-OM questionnaires contained identical measures with the exception that the post-OM questionnaire also included an instrument to evaluate participants' perceptions of the effectiveness of the program. Demographic information was collected using a study-specific instrument that included items about age, gender, education and job role.

The 39-item Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) was used to assess mindfulness. This instrument includes subscales for each of five empirically derived facets of mindfulness: observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging of inner experience and non-reactivity to inner experience (Baer et al. 2006). The possible score range for the non-reactivity facet is 7–35, while the range for all other facets is 8–40, with higher scores indicating higher levels of mindfulness. Assessment of its psychometric properties using student samples indicated adequate to excellent internal consistency (α = .75–.91 across the five facets), and it was found to correlate in the expected directions with measures of construct validity (Baer et al. 2006, 2008) including meditation experience (Baer et al. 2008). There is evidence that this measure is sensitive to change with Carmody and Baer (2008) reporting significant increases in all five facets following a course of MBSR compared to baseline. Furthermore, in this same study, increases in mindfulness as measured by the FFMQ were found to mediate the relationship between time spent in meditation practice and psychological functioning.

The ten-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) was used to measure the degree to which participants found their life situations stressful (Cohen et al. 1983). Possible scores range from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating higher levels of perceived stress. The PSS has been used extensively in research and has sound psychometric properties with internal consistency ranging from α = .84 to .89 (Cohen et al. 1983; Roberti et al. 2006) and a test–retest reliability correlation of r = .85 after 2 days (Cohen, et al. 1983).

The 21-item Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21) comprises three subscales used to measure symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress experienced in the past week (Lovibond and Lovibond 1995). Scores for each subscale range from 0 to 42, with higher scores indicating more frequent symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress. A composite score of negative emotional symptoms can be calculated by summing the responses to all 21 items (Lovibond 2011). Although the DASS-21 is not diagnostic, recommended subscale cut-off points indicative of clinically significant symptoms are depression > 9, anxiety > 7 and stress > 14 (Lovibond and Lovibond 1995). Psychometric analyses of the DASS-21 have yielded evidence that the instrument has good validity and reliability (Antony et al. 1998; Gloster et al. 2008). Internal consistency is good to excellent with a Cronbach's alpha of .94 reported for the total score (Gloster et al. 2008) and subscale alphas of .94 for depression, .87 for anxiety and .91 for stress (Antony et al. 1998). The DASS-21 is a short form of the DASS-42 which has been reported to have good stability with test–retest correlations over 2 weeks ranging between .71 and .81 Brown et al. (1997). The DASS-21 has demonstrated sensitivity to change in the context of a mindfulness intervention program (Schreiner and Malcolm 2008).

The 20-item Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) incorporates two mood scales, one measuring positive affect (e.g. enthusiastic and determined) and the other assessing negative affect (e.g. afraid and upset) (Watson et al. 1988). Scale scores can range from 10 to 50, with higher scores indicating higher levels of affect, that is higher scores on the positive affect scale correspond to higher levels of positive affect, while higher scores on the negative affect scale indicate that the respondent is experiencing higher levels of negative affect. The PANAS is widely used and has demonstrated good reliability and validity including high reliability, with Cronbach's alpha scores >.86 for positive affect and >.84 for negative affect (Watson et al. 1988). Test–retest reliability over 8 weeks has been reported to be .47 for ratings of affect during the past week (Watson et al. 1988).

The five-item Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) was used to measure global life satisfaction Diener et al. (1985). Scores for the scale range from 5 to 35 with higher scores indicating higher levels of life satisfaction. Prior research has demonstrated that the SWLS has good reliability and validity including a Cronbach's alpha of .87 and a 2-month test–retest correlation coefficient of .82 (Diener et al. 1985).

The 19-item Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI) was used to measure burnout defined as physical and psychological fatigue and exhaustion (Kristensen et al. 2005). The CBI is comprised of three subscales: personal burnout, work-related burnout and client-related burnout. The CBI is scored such that possible scores for each subscale range from 1 to 100, with higher scores indicating higher levels of burnout. The CBI has demonstrated satisfactory reliability and validity (Kristensen et al. 2005; Milfont et al. 2008). Cronbach's alphas have been reported to be between .85 and .87 (Kristensen et al. 2005) and between .79 and .87 (Milfont et al. 2008). Test–retest reliability has only been reported over a 3-year period and was above .51 for all subscales (Kristensen et al. 2005) suggesting, perhaps not surprisingly, that burnout levels do change over such a time frame.

The Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire Short Form (MSQ-SF) comprises a subset of 20 items from the 100-item Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ), a commonly used and well-validated measure of job satisfaction (Weiss et al. 1967). As well as a total score for general satisfaction, the MSQ-SF yields two subscale scores for intrinsic satisfaction and extrinsic satisfaction. The possible score range is 6 to 30 for the extrinsic subscale, 12 to 60 for the intrinsic subscale and 20 to 100 for the general score, with higher scores corresponding to higher levels of satisfaction. The reliability coefficients are generally high ranging from .84–.91 for intrinsic satisfaction, .77–.82 for extrinsic satisfaction and .87–.92 for general satisfaction. Test–retest reliability over 1 week for the overall general satisfaction score was reported to be .89 (Weiss et al. 1967).

The 30-item Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL) was developed to measure compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue in staff who support people who have experienced extremely stressful events (Stamm 2009). The ProQOL includes three subscales: compassion satisfaction, burnout and secondary traumatic stress. The latter two subscales assess compassion fatigue which has two dimensions differentiated by fear. In regard to secondary traumatic stress, a worker may be fearful that they will experience the same traumas as their clients. In contrast, burnout, as operationalised by the ProQOL, does not involve fear of potential trauma but instead is characterised by feelings of being unable to help clients (Stamm 2009). Scores for each subscale are standardised such that the average score is 50 (SD, 10). Higher scores for the compassion satisfaction subscale indicate higher levels of satisfaction with the respondent's ability to provide effective support to clients. By contrast, higher scores on the burnout and secondary traumatic stress subscales indicate higher levels of burnout and secondary traumatic stress, respectively. Acceptable levels of internal consistency have been reported for the ProQOL subscales: α = .87 for compassion satisfaction, α = .72 for burnout and α = .80 for compassion fatigue (Stamm 2009). While test–retest reliability does not appear to have been reported for this scale (Linley and Joseph 2007), associations have been demonstrated between mindfulness, as measured by the FFMQ, and the ProQOL subscales compassion satisfaction and burnout (Thomas and Otis 2010).

The five-item Santa Clara Brief Compassion Scale (SCBCS) was used to measure compassion towards others (Hwang et al. 2008). The SCBCS yields a possible total score ranging from 7 to 35 with higher scores associated with higher levels of compassion. Hwang et al. (2008) reported excellent internal consistency as demonstrated by a Cronbach's alpha of .90; however, test–retest reliability was not examined.

The 26-item Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) incorporates six subscales: self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness and over-identified (Neff 2003b). The scale developer defined self-compassion as involving “being touched by and open to one's own suffering, not avoiding or disconnecting from it, generating the desire to alleviate one's suffering and to heal oneself with kindness. Self-compassion also involves offering non-judgmental understanding to one's pain, inadequacies and failures, so that one's experience is seen as part of the larger human experience” (Neff 2003b). The total possible score ranges from 26 to 130 with higher scores indicating higher levels of self-compassion. Evidence to support the validity and reliability of the SCS has been reported in previous research (Neff 2003a). Neff (2003a) reported the internal consistency of the scale to be .92; however, test–retest reliability was not examined.

The Training Program Evaluation Questionnaire (TPEQ) included in the questionnaire administered at T2 was based on items used to assess the University of Massachusetts Medical School Stress Reduction Program (Santorelli and Kabat-Zinn 2002). A number of items were used to assess participants' perceptions of the benefits of the OM training program, using a rating scale of 1 to 10, where 10 indicated maximum benefit. The TPEQ also included items about perceived changes in participants' attitudes and behaviours that occurred as a direct result of participation in the OM training program. The response options for these items included ‘great positive change’, ‘some change’, ‘no change’ and ‘negative change’.

Procedure

Approval for the study was obtained by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee. A member of the research team (JJ) visited the worksites of each of the groups to provide a 1 h information session about the OM program and research study. Following the information sessions, a letter of invitation, together with the study explanatory statement and consent form, were mailed to eligible staff by the organization's project manager, a senior manager who reported directly to the Chief Executive Officer. Participation in the training program was voluntary, and staff who wanted to participate in the study were requested to return a signed consent form directly to the research team. In order to protect employees' privacy in relation to their reasons for participating or not participating in the training program, all subsequent contact with participants was made directly by the research team and the OM trainers. Upon receipt of a signed consent form by the research team, potential participants were scheduled to attend an individual interview with the OM trainer for their group. The purpose of the interview was to provide further information about the training program, answer any questions that the participants had about the program and to explain the importance of homework practice in maximising the benefit of the training program. During the interview, participants were also screened for current depression. As described in further detail below, the OM training program was in part adapted from a Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) manualised training program which was designed initially for relapse prevention of depression where participants are in remission at entry to the program (Segal et al. 2002b). While a recent literature review of MBSR training program outcomes found no adverse side effects associated with such programs (Praissman 2008), we believe caution was indicated in the application of a relatively untailored program to participants who may be currently depressed. However, no participants were diagnosed as depressed, and so, no staff who expressed interest in participating in the OM training program were excluded from the study.

Reimbursement of Participants

The pre-training interview and OM classes were conducted during standard work hours. Accordingly, the organization paid participants their standard wage for the time required to attend the interview and training program and to complete the study questionnaires. In addition, staff were reimbursed for travel to and from the interview and training venues. Homework activities were unpaid and undertaken in participants' own time.

Data Collection

Participants were asked to complete a 30-min self-administered questionnaire prior to commencement of the training program (time point 1, T1) and immediately following the conclusion of the training program (time point 2, T2). The initial questionnaire was completed immediately following the pre-training program interview. At the close of the last OM training group session, the trainer distributed the second questionnaire package to participants. Participants were provided with a reply-paid envelope to return their completed questionnaire to the research team at Monash University. A reminder letter was sent to participants who had not returned their second questionnaire within 2 weeks of the final group training session.

The Intervention—Occupational Mindfulness Training Program

OM is an adaptation of MBSR (Kabat-Zinn 1990), Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (Segal et al. 2002b), and some compatible sections of Seligman's work on positive psychology, particularly signature strengths (Seligman 2002). It also includes some basic cognitive therapy exercises. It has two essential, largely experiential, components: training-focused group work and homework. A training-focused group meets once weekly for eight sessions, each of 2 h duration. The group work is largely experiential, with participants engaging in the core mindfulness practices, including mindfulness of breathing, body scan meditation and mindful stretching, sitting and walking. These formal meditation methods are supported with informal activities such as a five-mindful breaths exercise and a 3-min breathing space for use throughout the day in the workplace and other environments. The second essential component is the homework which participants are expected to undertake for approximately 40 min daily, for 6 days of the week. Home practice consists of ‘formal’ and ‘informal’ mindfulness practices, including mindfulness of breathing, gentle stretching exercises and mindfulness of various daily activities such as eating or showering. Participants are provided with brief notes and audio-recordings to guide them through all homework practices.

A highly structured program was developed and included a detailed scripted manual to facilitate fidelity and training continuity across the three groups, particularly since each group was facilitated by a different trainer. The three trainers were mental health professionals with extensive experience in both mindfulness-based interventions and managing group dynamics, including two psychologists and a social worker. All trainers had previously received formal training in MBCT through Monash University.

Sessions were videotaped with the participants' permission (camera visual field focused on trainer) for the purposes of supervision and assessing treatment fidelity. An independent audit of the training was undertaken on a random selection of 20 % of sessions (five tapes) across the three training groups. Tape selection was stratified according to stage of training (early: sessions 2–4; late: sessions 5–8) and group. The randomization was undertaken by a researcher external to the project who set the seed for assigning each session a random number. Sessions were then sorted within each stage/group combination, and the session in each of these groups was selected with the lowest number. If a selected session did not have a videotape available, the next available session with the lowest number was selected.

To assess the treatment adherence, sessions were rated using the OM Adherence Scale, largely based on the Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy Adherence scale (MBCT-AS; Segal et al. 2002a). The MBCT-AS is a 17-item scale that has two subscales: one assessing therapist behaviours specific to MBCT (nine items) and the other assessing practices shared by MBCT and Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) (eight items). Each item is rated on a three-point scale: 0 = no evidence for item, 1 = slight evidence and 2 = definite evidence. The scale has been found to be reliable and successful in distinguishing MBCT from pure CBT (Segal et al. 2002a). Inter-rater reliability was found to be very high [intra-class correlation coefficient (2, 1) = 0.820], while internal consistency was good for mindfulness items (α = .886) but relatively low for CBT items (α = .415) (Segal et al. 2002a). In the current study, the instructions for items in the MBCT-AS were modified so as to be appropriate for OM (for example, item 12: “To what extent does the trainer try to educate participants about stress and the cognitive model?”).

The audit was completed by a clinical psychologist with training and experience in mindfulness-based group therapies but who was independent from the study and tape randomisation. Items that were not present in a particular session and not expected to appear were rated as ‘not applicable’. Mean scores for each trainer were calculated based on rated items. These scores ranged from 1.4 to 2.0 with an overall mean of 1.7 (SD, 0.2) which indicates adherence was good to excellent across the groups. The result is comparable to that of Segal et al. (2010) who reported a “very good” adherence score of 1.8.

Data Analysis

A pre-test–post-test design was used. Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests were used to check for normality of study variable distributions (Pallant 2005). For the total sample and the managers and support workers groups, nearly all variables yielded non-normal distributions. Accordingly, non-parametric descriptive statistics and statistical tests were used. For variables that were normally distributed, parametric tests were also conducted. Compared to findings yielded by the non-parametric equivalent tests, there were no differences in terms of significant findings, and thus, for the sake of consistency, results are presented for the non-parametric tests only. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to investigate differences in OM training program evaluation scores between managers and disability support workers and also between males and females. To investigate differences between managers and disability support workers with regard to the direct impact of the OM training program on attitudes and behaviours, chi-square tests were initially attempted but abandoned as the data failed the requirement that expected cell counts be at least 5. Instead, response options for these items were collapsed to create dichotomized variables: ‘positive change’ (comprised of ‘great positive change’ and ‘some positive change’) and ‘no positive change’ (consisting of ‘no change’ or ‘negative change’). Fisher's exact tests were then used to examine differences in these dichotomized items between managers and disability support workers. Similarly, Fisher's exact tests were also used to examine gender differences in perceived changes in attitudes and behaviour attributed to the training program. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test and Cohen's effect size were used to investigate changes in mindfulness and psychological wellbeing from pre- (T1) to post-training program (T2). The significance level was set at α = .05.

Results

All participants attended at least five of the eight group sessions, with 11 (32.4 %) attending all eight sessions, 15 (44.1 %) attending seven sessions, seven (20.6 %) attending six and one participant (2.9 %) attending five sessions.

Program Evaluation

The results presented in Table 2 are for Training Program Evaluation Questionnaire items that were rated on a scale of 1 to 10, where 10 was the best possible outcome.

For all five items in Table 2, disability support workers evaluated the program more positively than managers. The results of Mann–Whitney U tests indicated that these differences were significant for the first three items in Table 2: importance of program (U = 149.0, p < .05), recommendation of program to colleague (U = 154.5, p < .05) and program beneficial in work role (U = 141.0, p < .05). No significant differences for program evaluation items listed in Table 2 were found between males and females.

The results displayed in Table 3 are for questionnaire items from the TPEQ regarding the degree of perceived changes in attitudes and behaviours as a direct result of participation in the OM training program. It can be seen that positive changes were reported for each domain by 80–90 % of support workers and 37–95 % of managers. The results of Fisher's exact tests used to examine differences between managers and disability support workers for the items in Table 3, dichotomized into ‘positive change’ and ‘no positive change’, indicated that support workers reported significantly more positive change than managers with regard to feeling self-confident, p < .05. Similarly, Fisher's exact tests were used to examine differences between males and females with regard to perceived changes in attitudes and behaviours attributed to the training program, with no significant differences found for any of the items presented in Table 3.

To the TPEQ question, “Do you feel you got something of lasting value or importance as a result of taking the training program”, 100 % of disability support staff and 78 % of managers responded ‘yes’, while 22 % of the managers responded ‘unsure’.

Intervention Effects

The results of Wilcoxon signed rank tests used to examine median differences between pre- and post-OM training scores on the mindfulness and psychological wellbeing measures for the total sample are shown in Table 4.

As can be seen in Table 4, for the total sample, there were few significant pre- to post-OM program changes in scores on the psychological wellbeing measures. Stable outcomes included depressive symptoms as measured by the DASS-21; satisfaction with life as assessed with the Satisfaction With Life Scale; burnout as measured by the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (client-related, work-related and personal subscales); intrinsic job satisfaction and general job satisfaction as assessed by the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire Short Form; compassion satisfaction, burnout and secondary traumatic stress as measured by the ProQOL; compassion for others as assessed with the Santa Clara Brief Compassion Scale; and all domains of self-compassion as measured by the Self-Compassion Scale. In contrast, there was a significant increase in positive affect with a small effect size, as measured by the PANAS. For the facets of mindfulness examined with the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, there were apparent changes with noticeable increases in relation to describing, non-judging, non-reactivity and observing, with the latter yielding a significant increase with a medium effect size. Negative affect as measured by the PANAS and anxiety and negative emotional symptoms as assessed with the DASS-21 increased significantly from baseline to post-training, with medium effect sizes observed. In addition, perceived stress as measured by both the Perceived Stress Scale and the DASS-21 increased significantly following the OM training program, although the effect size was small in both instances. Extrinsic job satisfaction as examined with the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire Short Form decreased significantly from pre- to post-training, with a small effect size observed.

The analyses were also repeated separately for disability support workers and managers. Disability support workers reported significant increases in positive affect, negative affect and the observing facet of mindfulness from baseline to post-training. In addition, significant decreases in extrinsic and general job satisfaction from pre- to post-OM training were observed among disability support workers. Medium effect sizes were found for each of these post-training changes. For the managers, significant increases from baseline to post-training in the observing facet of mindfulness, anxiety and perceived stress as measured by the Perceived Stress Scale, but not the DASS-21, were found. The effect sizes for these changes were small, large and medium, for observing, anxiety and perceived stress, respectively.

Discussion

The aims of this preliminary investigation were to investigate the impact of the OM training program on mindfulness and a range of psychological wellbeing outcomes and to examine participants' perceptions of the benefits of the program.

Participants' evaluations of the OM program were very positive, particularly for the disability support workers who rated the OM training program 9.5 and 8.5 out of 10 with regard to benefit to their work role and client interactions, respectively. Support workers evaluated the program significantly more positively than managers in regard to three items: the importance of the program to them, whether they would recommend the program to a colleague and whether the program was beneficial in their work role. In relation to changes in attitudes and behaviours directly attributed to the program, positive changes were reported for each domain by between 80 % and 90 % of support workers and between 37 % and 95 % of managers. With regard to attitudinal and behavioural changes attributed to the OM program, there were no significant differences between managers and support workers, with the exception that support workers reported significantly more positive change in feelings of self-confidence. No significant differences between males and females were found with regard to participant's evaluation of the OM training program or perceived changes in attitudes and behaviours attributed to the program.

Various facets of mindfulness showed positive trends over the study period including a significant finding in the domain of ‘observing’, as one of five mindfulness factors. It is possible that the training program more effectively targets observation, than awareness, describing, non-judging and non-reactivity as measured by the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire.

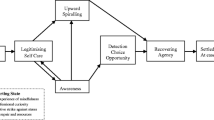

Stress as assessed using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) and the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21) increased significantly from T1 (prior to commencement of the OM program) to T2 (immediately following completion of the 8-week OM program) for the total sample. This is in contrast to prior research in which stress as measured by the PSS decreased in a sample of healthcare professionals following MBSR training (Shapiro et al. 2005). In the current study, although perceived stress increased post-intervention, 90 % of support workers and 79 % of managers reported a positive change in their ability to manage stress in an appropriate manner. One explanation for this finding is that the training program encouraged the participants to become more aware of their own stress, and therefore, they were more able to manage their stress. This explanation is also consistent with the finding that observing as measured by the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire increased, but in the absence of supporting evidence from other studies, this needs to be explored further in future research.

Pre-OM training levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms were low and remained in the normal (non-clinical) range post-intervention, although there was a significant increase in anxiety symptoms and overall negative emotional state from pre- to post-OM training for the total sample and the managers' group. Again, a plausible explanation for the increase in anxiety and overall negative emotional state is that the training encourages observation, leading to increased awareness of symptoms. There has been little prior research into the impact of workplace mindfulness training on depression and anxiety among employees, although the impact of MBSR training on depression in other vocational settings has been explored. The current finding that depressive symptoms did not change significantly from T1 to T2 is in contrast to earlier studies in which mindfulness-based interventions in vocational settings were associated with a reduction in symptoms of depression (Astin 1997; Jain et al. 2007; Shapiro et al. 1998). The present finding may be partially due to the initial low levels of depressive symptoms among participants prior to commencement of the OM program.

Positive affect and negative affect increased significantly after 8 weeks of OM training among the total sample and disability support workers. By contrast, previous researchers have generally found a decrease in negative affect following MBSR interventions. For example, Shapiro et al. (2007) reported a significant increase in positive affect and a significant decrease in negative affect among 22 psychotherapist trainees following a MBSR training program. In addition, Martin-Asuero and Garcia-Banda (2010) reported that negative affect among 29 healthcare professionals decreased significantly immediately following participation in a MBSR training program, while positive affect did not change. The present finding is also consistent with the above explanation of increased awareness of psychological states.

Satisfaction with life was not seen to change significantly from pre- to post-OM training, perhaps given the low power of the study. In contrast, Mackenzie et al. (2006) reported that scores for this construct increased significantly more in MBSR participants than control group participants. In a small randomized controlled trial, satisfaction with life increased more among participants who completed a MBSR training program than controls (19 % versus 0 %), although this difference was not significant (Shapiro et al. 2005). It is possible that there are inherent differences between the OM and MBSR programs with regard to their impact on global life satisfaction, although larger, controlled studies are necessary to explore any such differences.

Results for the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory suggest that the OM program did not have an impact on burnout, as operationalised by this measure. Similarly, there were no changes in compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue as assessed by the ProQOL. In previous studies in which the impact of mindfulness interventions on burnout was examined, the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) has been used. The MBI conceptualizes burnout as being comprised of three domains: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and a reduced sense of personal accomplishment in one's work role. While findings regarding changes in MBI subscale scores following mindfulness training have been equivocal, on balance prior research suggests that mindfulness training exerts the greatest benefit on the emotional exhaustion dimension of burnout (Cohen-Katz et al. 2005; Galantino et al. 2005; Mackenzie et al. 2006; Shapiro et al. 2005).

Extrinsic job satisfaction and general job satisfaction decreased significantly from T1 to T2 among disability support workers, while extrinsic job satisfaction decreased significantly for the total sample. In contrast, general and intrinsic job satisfaction remained stable from T1 to T2, for the total sample. The latter finding is consistent with that of Mackenzie et al. (2006) who reported no significant improvements in intrinsic job satisfaction among 16 participants in a 4-week MBSR program, compared to 14 participants in a wait-list control group. With respect to the former findings, it is possible that some part of the post-intervention decrease in extrinsic job satisfaction observed in the present study may be explained by the occurrence of salary package negotiations occurring within the organization during the same period that the OM training program was conducted.

However, these findings might also be understood in the context of the other results suggesting that participants were developing greater awareness of their current circumstances, whether positive or negative, internal or external. Mindfulness is not directly about changing circumstances but being ‘awake’ to what those circumstances are and changing how one relates to them. Lack of awareness of difficulties or avoidance of recognized difficulties means that one is not in a position to take skilful action (Segal et al. 2002b). Thus, if work circumstances are difficult, a mindfulness intervention may not necessarily lead to immediate improvements in job satisfaction. However, participants' increased awareness of dissatisfaction at work may be the first step toward positive change.

Compassion for others as measured by the Santa Clara Brief Compassion Scale was not seen to change from pre- to post-OM training. This appears to be the first study in which this scale was used to examine the impact of mindfulness training on compassion for others. Similarly, self-compassion scores did not change significantly from pre- to post-OM. By contrast, in controlled studies, self-compassion among human service workers was found to have increased significantly following participation in a MBSR training program (Shapiro et al. 2005, 2007). It is feasible that the addition of a loving-kindness meditation to the OM training program may lead to increased efficacy of the program with regard to increasing compassion towards self and others.

The findings of a highly favourable participant evaluation of the OM program alongside stable scores for many of the psychological wellbeing measures as well as increases in perceived stress, anxiety, negative emotional state and negative affect and decreases in job satisfaction immediately following the OM training program may seem somewhat paradoxical. The observed changes in perceived stress, anxiety, negative emotional symptoms, negative affect and job satisfaction may be explained by increased awareness of negative emotions and feelings arising from an increase in the observing facet of mindfulness, post-OM training. For example, it is not unreasonable to expect that awareness of negative affect might increase in the early stages of learning mindfulness techniques, as mindfulness involves increased awareness of all emotions, ‘positive’ and ‘negative’. Arguably, in the longer term as mindfulness develops further, the presence of negative affect may subside as participants gain increased awareness of their thoughts and feelings thereby choosing more adaptive coping responses when faced with stressors. This argument is consistent with recent research in which negative affect among healthcare professionals was found to decrease significantly from immediately following an MBSR intervention to 3 months post-intervention (Martín-Asuero and García-Banda 2010). Follow-up data for the current study is required to examine whether negative affect has decreased since T2. Another possible explanation for the paradoxical findings concerns the timing of questionnaire completion. The initial questionnaire was completed in January, shortly after the Christmas vacation. Accordingly, participants may have been more rested and feeling less stressed at the commencement of a new year. This may be evidenced by low scores at T1 for some measures, including low scores on the DASS-21 anxiety and depression subscales. In many work places, stress builds as the year progresses, and therefore, the deterioration observed for some study variables over the course of the study may have been influenced by the timing of questionnaire administration. Another feasible explanation for the unexpected deterioration in scores on a number of the psychological wellbeing measures from T1 to T2 is that through the group training sessions, participants realized that they were not alone in experiencing work-related stress and were therefore more willing to report psychological symptoms.

The present study had two main limitations which should be taken into account. First, as described above, the timing of questionnaire administration may have influenced the pre- to post-training program changes in some measures of psychological wellbeing. Second, the study included a small sample size and a non-experimental design. The lack of a control group precludes drawing firm conclusions regarding the impact of the OM program on participants' levels of mindfulness and psychological wellbeing. A large randomized controlled trial is necessary to determine the effectiveness of the OM program for staff in the disability sector.

In conclusion, this preliminary investigation appears to be the first in which a structured 8-week mindfulness-based training program was implemented within the disability services field in Australia. The OM program was positively evaluated by participants, and it appears that the program was associated with increases in positive affect and observing, alongside increases in perceived stress, negative affect, anxiety and negative emotional symptoms and a decrease in extrinsic job satisfaction. In addition, participants reported enhanced awareness of signs and sources of stress, and positive changes in self-care attitudes, behaviours and interactions with clients and colleagues. A number of measured outcomes did not change significantly from baseline to post-OM training. These included symptoms of depression, satisfaction with life, burnout, compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, compassion for others and self-compassion scores. It is possible that the OM program did not influence these constructs. It may be that additional exercises and practices could be incorporated in the OM training program to improve its efficacy with regard to improving these outcomes. The OM program needs to be examined in greater detail but holds significant potential to be transferred to other work settings in the future.

References

Antony, M. M., Bieling, P. J., Cox, B. J., Enns, M. W., & Swinson, R. P. (1998). Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychological Assessment, 10(2), 176–181.

Astin, J. A. (1997). Stress reduction through mindfulness meditation—Effects on psychological symptomatology, sense of control, and spiritual experiences. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 66(2), 97–106.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Lykins, E., Button, D., Krietemeyer, J., Sauer, S., et al. (2008). Construct validity of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15(3), 329–342. doi:10.1177/1073191107313003.

Belkic, K. L., Landsbergis, P. A., Schnall, P. L., & Baker, D. (2004). Is job strain a major source of cardiovascular disease risk? Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 30(2), 85–128.

Bellavia, G., & Frone, M. (2005). Work-family conflict. In J. Barling, E. K. Kelloway, & M. R. Frone (Eds.), Handbook of work stress (pp. 113–147). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc.

Bishop, S., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., et al. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 230–241. doi:10.1093/clipsy/bph077.

Borritz, M., Christensen, K. B., Bultmann, U., Rugulies, R., Lund, T., Andersen, I., et al. (2010). Impact of burnout and psychosocial work characteristics on future long-term sickness absence. Prospective results of the Danish PUMA Study among human service workers. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 52(10), 964–970.

Brown, T. A., Chorpita, B. F., Korotitsch, W., & Barlow, D. H. (1997). Psychometric properties of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) in clinical samples. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35(1), 79–89. doi:10.1016/s0005-7967(96)00068-x.

Burton, W. N., Chen, C.-Y., Conti, D. J., Schultz, A. B., Pransky, G., & Edington, D. W. (2005). The association of health risks with on-the-job productivity. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 47(8), 769–777. doi:10.1097/01.jom.0000158719.57957.c6.

Caplan, R. P. (1994). Stress, anxiety, and depression in hospital consultants, general practitioners, and senior health service managers. British Medical Journal, 309(6964), 1261–1263.

Carmody, J., & Baer, R. A. (2008). Relationships between mindfulness practice and levels of mindfulness, medical and psychological symptoms and well-being in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 31(1), 23–33.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 386–396.

Cohen, S., Janicki-Deverts, D., & Miller, G. E. (2007). Psychological stress and disease. Journal of the American Medical Association, 298(14), 1685–1687.

Cohen-Katz, J., Wiley, S., Capuano, T., Baker, D., & Shapiro, S. (2005). The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on nurse stress and burnout, Part II: A quantitative and qualitative study. Holistic Nursing Practice, 19(1), 26–35.

Davidson, R. J., Kabat-Zinn, J., Schumacher, J., Rosenkranz, M., Muller, D., Santorelli, S. F., et al. (2003). Alterations in brain and immune function produced by mindfulness meditation. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65(4), 564–570. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000077505.67574.e3.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13.

Dollard, M. F. (2003). Introduction: Context, theories and intervention. In M. F. Dollard, A. H. Winefield, & H. R. Winefield (Eds.), Occupational stress in the service professions. New York: Taylor & Francis.

European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. (2007). Fourth European Working Conditions Survey. Dublin: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions.

Fox, S., Spector, P., & Miles, D. (2001). Counterproductive work behavior (CWB) in response to job stressors and organizational justice: Some mediator and moderator tests for autonomy and emotions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 59, 291–309.

Galantino, M., Baime, M., Maguire, M., Szapary, P., & Farrar, J. (2005). Association of psychological and physiological measures of stress in health-care professionals during an 8-week mindfulness meditation program: Mindfulness in practice. Stress and Health, 21(4), 255–261. doi:10.1002/smi.1062.

Giga, S. I., Noblet, A. J., Faragher, B., & Cooper, C. L. (2003). The UK perspective: A review of research on organisational stress management interventions. Australian Psychologist, 38(2), 158–164.

Gloster, A. T., Rhoades, H. M., Novy, D., Klotsche, J., Senior, A., Kunik, M., et al. (2008). Psychometric properties of the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 in older primary care patients. Journal of Affective Disorders, 110, 248–259.

Godin, I., & Kittel, F. (2004). Differential economic stability and psychosocial stress at work: Associations with psychosomatic complaints and absenteeism. Social Science & Medicine, 58(8), 1543–1553.

Gray-Stanley, J. A. (2009). Stress and coping of direct care workers serving adults with intellectual/developmental disabilities. Chicago: University of Illinois.

Gray-Stanley, J. A., Muramatsu, N., Heller, T., Hughes, S., Johnson, T. P., & Ramirez-Valles, J. (2010). Work stress and depression among direct support professionals: The role of work support and locus of control. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 54(8), 749–761.

Hayes, A. M., & Feldman, G. (2004). Clarifying the construct of mindfulness in the context of emotion regulation and the process of change in therapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 255–262.

Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Witt, A. A., & Oh, D. (2010). The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 169–183. doi:10.1037/a0018555.

Hutchinson, S., & Purcell, J. (2010). Managing ward managers for roles in HRM in the NHS: Overworked and under-resourced. Human Resource Management Journal, 20(4), 357–374. doi:10.1111/j.1748-8583.2010.00141.x.

Hwang, J. Y., Plante, T., & Lackey, K. (2008). The development of the Santa Clara Brief Compassion Scale: An abbreviation of Sprecher and Fehr's Compassionate Love Scale. Pastoral Psychology, 56, 421–428. doi:10.1007/s11089-008-0117-2.

Jain, S., Shapiro, S., Swanick, S., Roesch, S. C., Mills, P. J., Bell, I., et al. (2007). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation versus relaxation training: Effects on distress, positive states of mind, rumination, and distraction. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 33(1), 11–21.

Jenkins, R., Rose, J., & Lovell, C. (1997). Psychological well-being of staff working with people who have challenging behavior. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 41(6), 502–511.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York: Delta.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life (1st ed.). New York: Hyperion.

Klatt, M. D., Buckworth, J., & Malarkey, W. B. (2009). Effects of low-dose mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR-ld) on working adults. Health Education & Behavior, 36(3), 601–614.

Koritsas, S., Iacono, T., Carling-Jenkins, R., & Chan, J. (2010). Exposure to challenging behaviour and support worker/house supervisor well-being. Melbourne: The Centre for Developmental Disability Health Victoria.

Kristensen, T. S., Borritz, M., Villadsen, E., & Christensen, K. B. (2005). The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work and Stress, 19(3), 192–207.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613.

LaMontagne, A., Louie, A., Keegel, T., Ostry, A., & Shaw, A. (2006). Workplace stress in Victoria: Developing a systems approach. Melbourne: Victorian Mental Health Promotion Foundation.

Lawson, D. A., & O'Brien, R. M. (1994). Behavioral and self-report measures of staff burnout in developmental disabilities. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 14(2), 37–54. doi:10.1300/J075v14n02_04.

Levi, L. (2005). Introduction: Spice of life or kiss of death? In C. Cooper (Ed.), Handbook of stress medicine and health. Boca Raton: CRC.

Linley, P. A., & Joseph, S. (2007). Therapy work and therapists' positive and negative well-being. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26(3), 385–403.

Lovibond, P. (2011). DASS FAQ Retrieved 14th January 2011, from http://www2.psy.unsw.edu.au/groups/dass/DASSFAQ.htm.

Lovibond, S., & Lovibond, P. (1995). Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales (2nd ed.). Sydney: Psychology Foundation.

Löwe, B., Unützer, J., Callahan, C. M., Perkins, A. J., & Kroenke, K. (2004). Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Medical Care, 42(12), 1194–1197.

Mackenzie, C. S., Poulin, P. A., & Seidman-Carlson, R. (2006). A brief mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention for nurses and nurse aides. Applied Nursing Research, 19(2), 105–109. doi:10.1016/j.apnr.2005.08.002.

Martín-Asuero, A., & García-Banda, G. (2010). The Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction program (MBSR) reduces stress-related psychological distress in healthcare professionals. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 13(2).

Maslach, C., & Florian, V. (1988). Burnout, job setting, and self-evaluation among rehabilitation counselors. Rehabilitation Psychology, 33(2), 85–93. doi:10.1037/h0091691.

Medibank Private Limited. (2008). The cost of workplace stress in Australia. Melbourne: Medibank Private Limited.

Milfont, T. L., Denny, S., Ameratunga, S., Robinson, E., & Merry, S. (2008). Burnout and wellbeing: Testing the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory in New Zealand teachers. Social Indicators Research, 89(1), 169–177.

Mitchell, G., & Hastings, R. P. (2001). Coping, burnout, and emotion in staff working in community services for people with challenging behaviours. American Journal of Mental Retardation, 106(5), 448–459.

Musich, S., Hook, D., Baaner, S., Spooner, M., & Edington, D. W. (2006). The association of corporate work environment factors, health risks, and medical conditions with presenteeism among Australian employees. American Journal of Health Promotion, 21(2), 127–136.

Neff, K. (2003a). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2, 223–250.

Neff, K. (2003b). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2, 85–102.

Noone, S. J., & Hastings, R. P. (2010). Using acceptance and mindfulness-based workshops with support staff caring for adults with intellectual disabilities. Mindfulness, 1, 67–73. doi:10.1007/s12671-010-0007-4.

Pallant, J. (2005). SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS for Windows (version 12) (2nd ed.). Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Praissman, S. (2008). Mindfulness-based stress reduction: A literature review and clinician's guide. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 20, 212–216.

Roberti, J. W., Harrington, L. N., & Storch, E. A. (2006). Further psychometric support for the 10-item version of the Perceived Stress Scale. Journal of College Counseling, 9(2), 135–147.

Rose, J., Jones, C., & Elliott, J. L. (2000). Differences in stress levels between managers and direct care staff in group homes. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 13(4), 276–282. doi:10.1046/j.1468-3148.2000.00025.x.

Santorelli, S., & Kabat-Zinn, J. (2002). Mindfulness-based stress reduction professional training curriculum guide and supporting materials: Integrating mindfulness meditation into medicine and health care. Worcester: University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Schreiner, I., & Malcolm, J. P. (2008). The benefits of mindfulness meditation: Changes in emotional states of depression, anxiety, and stress. Behaviour Change, 25(3), 156–168.

Segal, Z., Teasdale, J. D., Williams, J. M. G., & Gemar, M. C. (2002a). The Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy Adherence Scale: Inter-rater reliability, adherence to protocol and treatment distinctiveness. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 9, 131–138.

Segal, Z., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2002b). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. New York: Guilford.

Segal, Z., Bieling, P., Young, T., MacQueen, G., Cooke, R., Martin, L., et al. (2010). Antidepressant monotherapy vs sequential pharmacotherapy and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, or placebo, for relapse prophylaxis in recurrent depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(12), 1256–1264.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. Milsons Point: Random House Australia.

Shapiro, S., Schwartz, G., & Bonner, G. (1998). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on medical and premedical students. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 21(6), 581–599.

Shapiro, S., Astin, J., Bishop, S., & Cordova, M. (2005). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for health care professionals: Results from a randomized trial. International Journal of Stress Management, 12(2), 164–176.

Shapiro, S., Brown, K., & Biegel, G. (2007). Teaching self-care to caregivers: Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on the mental health of therapists in training. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 1(2), 105–115.

Singh, N. N., Lancioni, G. E., Winton, A. S. W., Wahler, R. G., Singh, J., & Sage, M. (2004). Mindful caregiving increases happiness among individuals with profound multiple disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 25, 207–218.

Stamm, B. H. (2009). The concise ProQOL manual. Pocatello: ProQOL.org.

Strand, M., Benzein, E., & Saveman, B. I. (2004). Violence in the care of adult persons with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 13(4), 206–514.

Tennant, C. (2001). Work-related stress and depressive disorders. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 51, 697–704.

Thomas, J. T., & Otis, M. D. (2010). Intrapsychic correlates of professional quality of life: Mindfulness. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 1(2), 83–98.

Thomas, C., & Rose, J. (2010). The relationship between reciprocity and the emotional and behavioural responses of staff. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 23(2), 167–178.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070.

Weiss, D. J., Dawis, R. V., England, G. W., & Lofquist, L. H. (1967). Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire. Minneapolis: Industrial Relations Center, University of Minnesota.

World Health Organization. (2010). Occupational health: Stress at the workplace. Retrieved 14 Dec 2010. From: http://www.who.int/occupational_health/topics/stressatwp/en/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brooker, J., Julian, J., Webber, L. et al. Evaluation of an Occupational Mindfulness Program for Staff Employed in the Disability Sector in Australia. Mindfulness 4, 122–136 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0112-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0112-7