Abstract

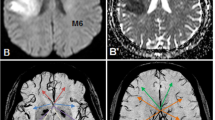

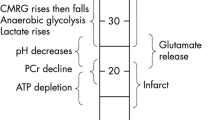

The mismatch between a larger perfusion lesion and smaller diffusion lesion on magnetic resonance imaging is a validated signal of the ischemic penumbra, namely the region at risk in acute ischemic stroke that is critically hypoperfused and the target of reperfusion therapies. Clinical trials have shown strong correlations between reperfusion in mismatch patients and improved clinical outcomes. Attenuation of infarct growth is associated with reperfusion and corresponding clinical gains. Using computed tomography perfusion, the mismatch between relative cerebral blood flow or cerebral blood volume and perfusion delay is a comparable penumbral marker. Automated techniques allow rapid quantitative assessment of mismatch with thresholding to exclude benign oligemia. The penumbra is often present beyond the current 4.5-h time window, defined for the use of intravenous tPA. Treatment beyond this time point remains investigational. Although the efficacy of thrombolysis in mismatch patients requires further validation in randomized trials, there is now sufficient evidence to recommend that advanced neuroimaging of mismatch should be used for selection of delayed therapies in phase 3 trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

NINDS. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(24):1581–7.

Lees KR, et al. Time to treatment with intravenous alteplase and outcome in stroke: an updated pooled analysis of ECASS, ATLANTIS, NINDS, and EPITHET trials. Lancet. 2010;375(9727):1695–703.

Sandercock P, et al. The third international stroke trial (IST-3) of thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. Trials. 2008;9(1):37.

Donnan GA, et al. Penumbral selection of patients for trials of acute stroke therapy. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(3):261–9.

Astrup J, Siesjo BK, Symon L. Thresholds in cerebral ischemia—the ischemic penumbra. Stroke. 1981;12(6):723–5.

Darby DG, et al. Pathophysiological topography of acute ischemia by combined diffusion-weighted and perfusion MRI. Stroke. 1999;30(10):2043–52.

Hacke W, et al. The Desmoteplase in Acute Ischemic Stroke Trial (DIAS): a phase II MRI-based 9-hour window acute stroke thrombolysis trial with intravenous desmoteplase. Stroke. 2005;36(1):66–73.

Furlan AJ, et al. Dose Escalation of Desmoteplase for Acute Ischemic Stroke (DEDAS): evidence of safety and efficacy 3 to 9 hours after stroke onset. Stroke. 2006;37(5):1227–31.

Parsons MW, et al. Acute ischemic stroke: imaging-guided tenecteplase treatment in an extended time window. Neurology. 2009;72(10):915–21.

Hacke W, et al. Intravenous desmoteplase in patients with acute ischaemic stroke selected by MRI perfusion-diffusion weighted imaging or perfusion CT (DIAS-2): a prospective, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(2):141–50.

Smith WS, et al. Safety and efficacy of mechanical embolectomy in acute ischemic stroke: results of the MERCI trial. Stroke. 2005;36(7):1432–8.

Smith WS, et al. Mechanical thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke: final results of the multi MERCI trial. Stroke. 2008;39(4):1205–12.

Furlan A, et al. Intra-arterial prourokinase for acute ischemic stroke. The PROACT II study: a randomized controlled trial. Prolyse in acute cerebral thromboembolism. JAMA. 1999;282(21):2003–11.

Parsons MW, et al. A randomized trial of tenecteplase and alteplase for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(12):1099–107.

Baker WL, et al. Neurothrombectomy devices for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke: state of the evidence. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(4):243–52.

Sit SP. The penumbra pivotal stroke trial: safety and effectiveness of a new generation of mechanical devices for clot removal in intracranial large vessel occlusive disease. Stroke. 2009;40(8):2761–8.

Costalat V, et al. Rescue, Combined, and stand-alone thrombectomy in the management of large vessel occlusion stroke using the solitaire device: a prospective 50-patient single-center study: timing, safety, and efficacy. Stroke. 2011;42(7):1929–35.

Saver J, et al. Primary Results of the SOLITAIRE FR With the Intention for Thrombectomy (SWIFT) Multicenter, Randomized Clinical Trial. International Stroke Conference Late-breaking abstract. 2012.

Khatri P, et al. Methodology of the Interventional Management of Stroke III Trial. Int J Stroke. 2008;3(2):130–7.

Ackerman RH, et al. Positron imaging in ischemic stroke disease using compounds labeled with oxygen 15. Initial results of clinicophysiologic correlations. Arch Neurol. 1981;38(9):537–43.

Baron JC, et al. Local interrelationships of cerebral oxygen consumption and glucose utilization in normal subjects and in ischemic stroke patients: a positron tomography study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1984;4(2):140–9.

Wise RJ, et al. Serial observations on the pathophysiology of acute stroke. The transition from ischaemia to infarction as reflected in regional oxygen extraction. Brain. 1983;106(Pt 1):197–222.

Baron JC, et al. Reversal of focal "misery-perfusion syndrome" by extra-intracranial arterial bypass in hemodynamic cerebral ischemia. A case study with 15O positron emission tomography. Stroke. 1981;12(4):454–9.

Barber PA, et al. Identification of major ischemic change. Diffusion-weighted imaging versus computed tomography. Stroke. 1999;30(10):2059–65.

Warach S, et al. Acute human stroke studied by whole brain echo planar diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol. 1995;37(2):231–41.

Kidwell CS, et al. Thrombolytic reversal of acute human cerebral ischemic injury shown by diffusion/perfusion magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol. 2000;47(4):462–9.

Chemmanam T, et al. Ischemic diffusion lesion reversal is uncommon and rarely alters perfusion-diffusion mismatch. Neurology. 2010;75(12):1040–7.

Campbell BCV, et al. The infarct core is well represented by the acute diffusion lesion: sustained reversal is infrequent. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:50–6.

Olivot JM, et al. Optimal Tmax threshold for predicting penumbral tissue in acute stroke. Stroke. 2009;40(2):469–75.

Christensen S, et al. Optimal perfusion thresholds for prediction of tissue destined for infarction in the combined EPITHET and DEFUSE dataset. Stroke. 2010;41:e297.

Zaro-Weber O, et al. Maps of time to maximum and time to peak for mismatch definition in clinical stroke studies validated with positron emission tomography. Stroke. 2010;41(12):2817–21.

Davis SM, et al. Effects of alteplase beyond 3 h after stroke in the Echoplanar Imaging Thrombolytic Evaluation Trial (EPITHET): a placebo-controlled randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(4):299–309.

Olivot JM, et al. Relationships between infarct growth, clinical outcome, and early recanalization in diffusion and perfusion imaging for understanding stroke evolution (DEFUSE). Stroke. 2008;39(8):2257–63.

Barber PA, et al. Prediction of stroke outcome with echoplanar perfusion- and diffusion-weighted MRI. Neurology. 1998;51(2):418–26.

Baird TA, et al. Persistent poststroke hyperglycemia is independently associated with infarct expansion and worse clinical outcome. Stroke. 2003;34(9):2208–14.

Parsons MW, et al. Acute hyperglycemia adversely affects stroke outcome: a magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy study. Ann Neurol. 2002;52(1):20–8.

Allport LE, et al. Elevated hematocrit is associated with reduced reperfusion and tissue survival in acute stroke. Neurology. 2005;65(9):1382–7.

Singhal AB. Oxygen therapy in stroke: past, present, and future. Int J Stroke. 2006;1(4):191–200.

Campbell BCV, et al. Assessing response to stroke thrombolysis: validation of 24 hour multimodal MRI. Arch Neurol. 2012;69:46–50.

Ebinger M, et al. Expediting MRI-based proof-of-concept stroke trials using an earlier imaging end point. Stroke. 2009;40(4):1353–8.

Campbell BCV, et al. Visual assessment of perfusion-diffusion mismatch is inadequate to select patients for thrombolysis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;29(6):592–6.

Straka M, Albers GW, Bammer R. Real-time diffusion-perfusion mismatch analysis in acute stroke. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;32(5):1024–37.

Wintermark M, et al. Comparison of admission perfusion computed tomography and qualitative diffusion- and perfusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in acute stroke patients. Stroke. 2002;33(8):2025–31.

Parsons MW, et al. Perfusion computed tomography: prediction of final infarct extent and stroke outcome. Ann Neurol. 2005;58(5):672–9.

Campbell BCV, et al. Cerebral blood flow is the optimal ct perfusion parameter for assessing infarct core. Stroke. 2011;42:3435–40.

Bivard A, et al. Defining the extent of irreversible brain ischemia using perfusion computed tomography. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;31(3):238–45.

Albers GW, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging profiles predict clinical response to early reperfusion: the diffusion and perfusion imaging evaluation for understanding stroke evolution (DEFUSE) study. Ann Neurol. 2006;60(5):508–17.

Nagakane Y, et al. EPITHET: Positive result after reanalysis using baseline diffusion-weighted imaging/perfusion-weighted imaging co-registration. Stroke. 2011;42(1):59–64.

Ma H, et al. A multicentre, randomized, double blinded, placebo controlled phase 3 study to investigate EXtending the time for Thrombolysis in Emergency Neurological Deficits (EXTEND). Int J Stroke. 2012;7:74–80.

Parsons MW, et al. Pretreatment diffusion- and perfusion-MR lesion volumes have a crucial influence on clinical response to stroke thrombolysis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30(6):1214–25.

Campbell BCV, et al. Regional very low cerebral blood volume predicts hemorrhagic transformation better than diffusion-weighted imaging volume and thresholded apparent diffusion coefficient in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2010;41(1):82–8.

Lansberg MG, et al. RAPID automated patient selection for reperfusion therapy: a pooled analysis of the Echoplanar Imaging Thrombolytic Evaluation Trial (EPITHET) and the Diffusion and Perfusion Imaging Evaluation for Understanding Stroke Evolution (DEFUSE) study. Stroke. 2011;42(6):1608–14.

De Silva DA, et al. The benefits of intravenous thrombolysis relate to the site of baseline arterial occlusion in the Echoplanar Imaging Thrombolytic Evaluation Trial (EPITHET). Stroke. 2010;41(2):295–9.

Albers G, et al. Results of DEFUSE 2: imaging endpoints. Stroke. 2012;43:A52.

Mishra NK, et al. Mismatch-based delayed thrombolysis: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 2010;41(1):e25–33.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Davis, S., Campbell, B., Christensen, S. et al. Perfusion/Diffusion Mismatch Is Valid and Should Be Used for Selecting Delayed Interventions. Transl. Stroke Res. 3, 188–197 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12975-012-0167-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12975-012-0167-8