Abstract

l-Asparaginase (E.C. 3.5.1.1) is used as a therapeutic agent in the treatment of acute childhood lymphoblastic leukemia. It is found in a variety of organisms such as microbes, plants and mammals. In plants, l-asparaginase enzymes are required to catalyze the release of ammonia from asparagine, which is the main nitrogen-relocation molecule in these organisms. An Indian medicinal plant, Withania somnifera was reported as a novel source of l-asparaginase. l-Asparaginase from W. somnifera was cloned and overexpressed in E. coli. The enzymatic properties of the recombinant enzyme were investigated and the kinetic parameters (Km, kcat) for a number of substrates were determined. The kinetic parameters of selected substrates were determined at various pH and the pH- and temperature-dependence profiles were analyzed. WA gene successfully cloned into E. coli BL21 (DE3) showed high asparaginase activity with a specific activity of 17.3 IU/mg protein.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The interest in l-asparaginases arose due to their antitumor activity. Unlike normal cells, malignant cells can only slowly synthesize l-asn and are dependent on an exogenous supply (Lee et al. 1989). In contrast, normal cells are protected from Asn-starvation due to their ability to produce this amino acid (Duval et al. 2002). The antineoplastic activity results from depletion of the circulating pools of l-asn by l-asparaginase (Lee et al. 1989). The l-asparaginases of Erwinia and E. coli have been employed for many years as effective drugs in the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia and leukemia lymphosarcoma (Kristiansen et al. 1970; Kozak et al. 2002; Graham 2003), but their therapeutic response rarely occurs without some evidence of toxicity (Duval et al. 2002). Their main side effects are anaphylaxis, pancreatitis, diabetes, leucopoenia, neurological seizures and coagulation abnormalities that may lead to intracranial thrombosis or hemorrhage (Duval et al. 2002). Because the l-asparaginases from E. coli and Erwinia possess different immunological specificities, they offer an important alternative therapy if a patient becomes hypersensitive to one of the enzymes (Lee et al. 1989).

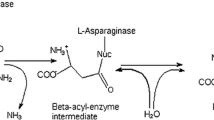

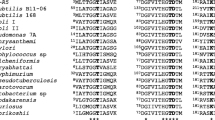

In comparison to the bacterial enzymes, the plant enzymes have been studied less thoroughly. In plants, l-asparagine is the major nitrogen storage and transport compound and it may also accumulate under stress conditions (Bruneau et al. 2006). There are two groups of such proteins, called potassium-dependent and potassium-independent asparaginases (Sodek et al. 1980; Sieciechowicz et al. 1988). Both enzyme groups have significant levels of sequence similarity. The plant asparaginase amino acid sequences did not have any significant similarity with microbial asparaginase but was 23% identical and 66% similar to a human glycosylasparaginase (Lough et al. 1992). The crystal structure of plant l-asparaginase showed significant similarity with bacterial as well as threonine aspartase (Karolina et al. 2006).

Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal was considered a rasayana herb, which works on a non-specific basis to increase health and longevity. The species name somnifera means “sleep-making” in Latin, indicating to its sedating properties. Extracts of the fruits, leaves and seeds of W. somnifera L. were traditionally used in the Ayurvedic system as aphrodisiacs, diuretics and for treating memory loss. W. somnifera L. was reported as a potential source for l-asparaginase (Oza et al. 2009) and the purified enzyme was shown to have anti-tumor activity on cell cultures (Oza et al. 2010).

The toxicity is partially attributable to the glutaminase activity of these enzymes (Howard and Carpenter 1972). l-asparaginases with high specificity for l-asparagine and negligible activity against l-glutamine are reported to be less troublesome during the course of anti-cancer therapy (Hawkins et al. 2004). The interest in l-asparaginase from W. somnifera L. arose from the fact that it has less toxicity compared to bacterial l-asparaginase (Oza et al. 2010). Despite the therapeutic potential of WA, this enzyme is less characterized, compared to other l-asparaginases. Detailed studies of protein and large scale production of the therapeutic protein through recombinant enzyme have not been reported so far from W. somnifera L. Therefore, in this study expression, purification and characterization of recombinant l-asparaginase from W. somnifera is reported for the first time.

Materials and methods

Materials

All degenerate oligonucleotides and l-asparaginase-specific primers used in this study were synthesized by MWG (India). Oligo (dT)-anchor primer and all other chemicals such as M-MuLV reverse transcriptase, DTT, RNase inhibitor and many more for amplification of cDNA were obtained from Bangalore Genei (India). Taq DNA polymerase and MgCl2 were from Sigma-Aldrich Co (USA). Restriction enzyme HindIII and XholI was obtained from NEB (UK). Qiagen Plasmid Maxi Kit and transformation chemicals were from Qiagen (Germany). l-Asparagine was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Co.

Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal was collected from the Botanical garden, Department of Biosciences, Sardar Patel University, Vallabh Vidyanagar, Gujarat (India). A voucher specimen of the plant was submitted to the department herbarium. Identification of the plant was confirmed through comparison with a herbarium specimen number 10337.

RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

One gram of immature, 10-day-old fruits was washed thoroughly with tap water followed by sterile distilled water to remove extraneous material and homogenized in liquid nitrogen using a homogenizer. Extraction of total RNA was carried out using TRI reagent (Sigma). Sequences homologous to WA were sought in the NCBI using BLAST. A cDNA sequence of l-asparaginase from A.thaliana (GenBank accession no: Z34884) was used for cDNA synthesis. Reverse transcriptase PCR was used to amplify the full-length cDNA. 1 U of DNase was added into total RNA sample (5 μg), mixed properly and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. DNase was inactivated by incubation at 75 °C for 10 min and it was carried out before RT-PCR. The cDNA synthesis was carried out in a total volume of 20 μl, containing 100 ng of total RNA, 100 pmol of random hexamer, DEPC treated water, RNase inhibitor, DTT, RT Buffer, dNTP mix and M-MuLV reverse transcriptase. cDNA was amplified through PCR using the heterologous primers synthesized to the 5′-region of the cDNA (5′-ATG GGC GGC TGG AGC ATT GC-3′) and to the 3′-end of the cDNA (5′-CTT TCA GGC TCA GGC CTT TA-3′), 100 pmol of both primer, 100 ng cDNA, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 5 μl 10× Taq buffer and 2 units of Taq DNA polymerase (Bangalore Genei). The PCR procedure comprised 35 cycles of 1.0 min at 95 °C, 1.0 min at 54 °C and 1.0 min at 72 °C. A final extension time at 72 °C for 5 min was performed after the 35 cycles. The resulting PCR amplicon was sequenced in multicolumn sequencer (ABI, USA). The sequence was validated by BLASTn and submitted to NCBI.

Cloning and overexpression of WsA

For sticky end ligation, the primers were modified in such a manner that they included the RE sites at both end of the PCR amplicon. The following primers were used WSF: 5′-GGC TTC TTA CTC GAG AAT GGG CGG CTG GAG CAT TGC-3′ (XholI site is underlined) and the reverse primer WSR: 5′-GGC TTC TTA AAG CTT CTT TCA GGC TCA GGC CTT TA-3′ (HindIII site is underlined). The resulting PCR amplicon which was obtained through RTPCR was re-amplified with the modified primers with the same condition as above. The modified amplified product and plasmid expression vector pRSET A (Invitrogen USA) were digested with HindIII and XholI (NEB, USA). The digested PCR product and plasmid vector were run on agarose electrophoresis and purified from the gel. The purified product was ligated into pRSET A using T4 ligase enzyme. The resulting expression construct pRSET A was used to transform competent DH5α E. coli cells. The transformed E. coli cells, harboring plasmid pRSET A, were grown at 37 °C in 100 ml LB medium containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin. The plasmid was isolated from DH5α E. coli and used to transform competent BL21 (DE3) E. coli. The cells were grown into LB agar plate containing ampicillin and X-gal. The recombinant clones were identified by blue/white selection and grown at 37 °C in 500 ml LB medium containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin. Synthesis of WsA was induced by the addition of 1 mM IPTG when the absorbance at 600 nm was 0.6–0.8 (Sambrook et al. 1989).

Purification of WsA

Five hours after induction by IPTG, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000g and 4 °C for 20 min. Cells obtained from culture (about 2 g of wet weight) were resuspended in 5 ml potassium phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 6.5), sonicated and centrifuged at 14,000g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and used for purification. The GeNei™ His-Tag fusion protein purification kit containing Nickel CL-Agarose column (2.5 × 10.0 cm) was used for the purification of WsA. The fractions collected (1 ml) were assayed for asparaginase activity by Nessler’s reagent method (Wriston and Yellin 1973) and protein (A280) estimation (Lowry et al. 1951). The purified enzyme was dialyzed to remove salt.

Kinetic analysis

Steady-state kinetic measurements were performed in 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 6.5 at 37 °C, by varying the concentration of the substrate l-asn. The kinetic parameters kcat, Km and Vmax were calculated by non-linear regression analysis of experimental steady-state data. Kinetic data kcat and Km were calculated using the GraFit program (Erithacus Software Ltd.).

pH and temperature effect on activity

The pH profile of WsA was studied using the following buffers, all at 0.05 M final concentration at 37 °C with different buffers: 0.01 M sodium acetate (pH 4.0–5.5), 0.01 M Na2HPo4/NaH2Po4 (pH 6.0–7.0) and 0.01 M sodium borate buffer (pH 7.5–9.0), in a range of 4.0–9.0 and data were analyzed through statistical software. The dependence of the reaction rate on temperature was evaluated by measuring enzyme activity for l-asn, at different temperature values under the same conditions reported above. The data were analyzed by the SPSS software.

Results

cDNA synthesis by reverse transcription

The total RNA yield obtained through TRI method from W. somnifera L. was of good quality and suitable for further use. The DNase-treated RNA was used as a template for cDNA synthesis. The cDNA for l-asparaginase obtained was amplified by PCR. The PCR product obtained was a single band of around 850 bp in agarose gel electrophoresis. The PCR amplicon was sequenced using both forward and reverse primers in a multicolumn sequencer (ABI). The sequence was validated with BLAST and submitted to gene bank (FJ645259).

Cloning and overexpression of WsA

To select the required expression product, prSET-A vector was chosen. The amplified product and prSET-A were digested with HindIII and XholI, respectively, and the digested PCR amplicon was cloned into the T7 expression vector pRSET A. The fusion product was named pr/WsA. The pr/WsA plasmid was used to initially transform into E. coli DH5α. The plasmid from DH5α E. coli cells was purified and used to transform expression host E. coli BL21 (DE3). Cell-free extract of the E. coli BL21 (DE3) showed high asparaginase activity with a specific activity of 17.3 IU/mg protein.

Purification of WsA

WsA was purified in a one-step procedure (Table 1). In the purification scheme, a His-Tag fusion protein purification Nickel CL-Agarose column was employed. Non-pre-treated enzyme extract was applied directly to the Nickel CL-Agarose column equilibrated with 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 7.5. The enzyme was adsorbed at pH 6.5 and eluted specifically by breaking the His-Tag. The purity of the final WsA preparation was evaluated by SDS-PAGE, which showed the presence of a single polypeptide chain (Fig. 1).

Kinetic analysis

The kinetic properties of the WsA were investigated. The kcat and K m parameters for substrate were determined by steady-state kinetic analysis (Table 2). The Km values for the recombinant l-asparaginase with l-asparagine and l-glutamine were determined as 0.075 and 4.5 mM, respectively. The catalytic constant kcat of WsA is significantly higher than that of the recombinant l-asparaginase from E. coli (Km; 0.085 and 0.058 mM and kcat; −31.4 and 23.8 × 103 s−1) (Kotzia and Labrou 2005, 2007). The glutaminase activity was responsible for side effects during treatment (Hawkins et al. 2004). The purified enzyme showed very low glutaminase activity, which is about 2% of that of l-asparaginase activity. The activity was significantly lower than that exhibited by the E. coli and Erwinia chrysanthemi enzymes (Howard and Carpenter 1972).

Effect of temperature and pH on enzyme activity

The optimum pH for WsA enzyme was found to be 8.0 (Fig. 2a) similar to that of E. coli and the wild-type enzyme which also had pH optima around 8.5 (Oza et al. 2009). The temperature optimum (37 °C) of the enzyme (Fig. 2b) is also similar to all other reported bacterial sources which are already being used in the treatment of leukemia.

Discussion

The role of l-asparaginase has been studied for the past 30 years. It plays a unique role in the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. The production of plant l-asparaginase in large quantities was quite difficult compared to microorganisms. Currently, l-asparaginase for the treatment of ALL is produced from microorganisms. A major drawback of using microorganisms as a source of this drug is a number of adverse effects of the enzyme. As a viable alternative to bacterial l-asp we selected a plant gene as a source to overcome the limitations of the bacterial enzyme. It is evident from the results that the l-asparaginase gene of WA has successfully been cloned and expressed at a high level in E. coli. The purified enzyme showed a high level of activity at 95 IU/ml. l-Asparaginase production by E. coli and E. chrysanthemi has been studied previously. However, research on molecular cloning and gene expression of l-asparaginase from plants has scarcely been reported. Gilbert et al. (1986) and Liu et al. (1996) have cloned and expressed E. coli and E. chrysanthemil-asparaginase gene into E. coli. The enzyme activities of these recombinant strains were 49 and 106 IU/ml, respectively. In the present study, lac and tac promoters were used along with IPTG, for the induction of the enzyme. The recombinant strain produced up to eightfold higher activity as compared to the wild-type E. coli; hence, the recombinant strain is suitable for the production of l-asparaginase. The purification of l-asparaginase could be achieved relatively easily due to a His-Tag in the recombinant protein. The protein was purified with the help of affinity chromatography.

A comparison of the enzyme characters of recombinant W. somnifera and that of E. coli and E. carotovora indicate that the WsA enzyme is superior in many parameters. While the optimum temperature and pH for the enzyme activity were similar, the l-glutaminase activity was much lower. A major reason for the undesirable side effects of the bacterial enzyme is their glutaminase activity (Howard and Carpenter 1972). Moreover, the enzyme turnover rate of the WsA enzyme was much higher than the bacterial enzyme. The constant kcat of WsA is higher than that of l-asparaginase from E. coli (Kotzia and Labrou 2005, 2007). The purified enzyme exhibited very low l-glutaminase activity, which is about 2% of that of l-asparaginase activity which is significantly lower than that exhibited by the E. coli and E. chrysanthemi enzymes (Narta et al. 2007). The Km value of WsA indicates that the enzyme efficiency is similar to the wild-type enzyme (Oza et al. 2009). The optimum pH and temperature of WsA were similar to other reported sources such as E. coli and wild-type W. somnifera L. (Gilbert et al. 1986; Oza et al. 2009).

In conclusion, in the present study, a new l-asparaginase from W. somnifera L. has been successfully cloned, expressed and characterized. The results of the present work form the basis for a rational and combinatorial design of new engineered forms of WsA with improved specificity and enhanced catalytic efficiency toward l-asn for future therapeutic use.

Abbreviations

- WA:

-

Withania somniferal-asparaginase

- WsA:

-

Recombinant l-asparaginase

- Tas1:

-

Threonine aspartase (taspase1)

- PDB:

-

Protein Data Bank

- LB:

-

Luria broth

References

Bruneau L, Chapman R, Marsolais F (2006) Co-occurrence of both l-asparaginase subtypes in arabidopsis: At3gl6150 encodes a K+-dependent l-asparaginase. Planta 224:668–679

Duval M, Suciu S, Ferster A, Rialland X, Nelken B, Lutz P, Benoit Y, Robert A, Manel AM, Vilmer E, Otten J, Philippe N (2002) Comparison of Escherichia coli-asparaginase with Erwinia-asparaginase in the treatment of childhood lymphoid malignancies: results of a randomized European Organization for research and treatment of cancer-children’s leukemia group phase 3 trial. Blood 99:2734–2739

Gilbert HJ, Blazek R, Bullman HMS, Minton NP (1986) Cloning and expression of the Erwinia chrysanthemi asparaginase gene in Escherichia coli and Erwinia carotovora. J Gen Microbiol 132:151–160

Graham ML (2003) Pegaspargase: a review of clinical studies. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 55:1293–1302

Hawkins DS, Park JR, Thomson BG, Felgenhauer JL, Holcenberg JS, Panosyan EH, Avramis VI (2004) Asparaginase pharmacokinetics after intensive polyethylene glycol-conjugated l-asparaginase therapy for children with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Clin Cancer Res 10:5335–5341

Howard JB, Carpenter FH (1972) l-Asparaginase from Erwinia carotovora. Substrate specificity and enzymatic properties. J Biol Chem 247:1020–1030

Karolina M, Grzegorz B, Mariusz J (2006) Crystal structure of plant asparaginase. J Mol Biol 360:105–116

Kotzia GA, Labrou NE (2005) Cloning, expression and characterization of Erwinia carotovoral-asparaginase. J Biotechnol 119:309–323

Kotzia GA, Labrou NE (2007) l-Asparaginase from Erwinia Chrysanthemi 3937: cloning, expression and characterization. J Biotechnol 127:657–669

Kozak M, Borek D, Janowski R, Jaskolski M (2002) Crystallization and preliminary crystallographic studies of five crystal forms of Escherichia colil-asparaginase II (Asp90Glu mutant). Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 58:130–132

Kristiansen T, Einarsson M, Sundberg L, Porath J (1970) Purification of l-asparaginase from E. coli by specific adsorption and desorption. FEBS Lett 7:294–296

Lee SM, Wroble MH, Ross JT (1989) l-Asparaginase from Erwinia carotovora. An improved recovery and purification process using affinity chromatography. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 22:1–11

Liu JJ, Li J, Wu WT, Hu MQ (1996) Cloning and expression of the E.coli asparaginase gene in Escherichia coli. J Chin Pharm Univ 27:696–700

Lough TJ, Reddington BD, Grant MR, Hill DF, Reynolds PHS, Farnden KJF (1992) The isolation and characterization of a cDNA clone encoding l-asparaginase from developing seeds of Lupin (Lupinus arboreus). Plant Mol Biol 19:391–399

Lowry OH, Rosenbrough NJ, Farr LA, Randal RJ (1951) Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 193:265–267

Narta UK, Kanwar SS, Azmi W (2007) Pharmacological and clinical evaluation of l-asparaginase in the treatment of leukemia. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 61:208–221

Oza VP, Trivedi SD, Parmar PP, Subramanian RB (2009) Withania somnifera L. (Ashwagandha): a novel source of l-asparaginase. J Integr Plant Biol 51:201–206

Oza VP, Kumar S, Parmar PP, Subramanian RB (2010) Anti-cancer properties of highly purified l-asparaginase from Withania somnifera L. against acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 160:1833–1840

Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T (1989) In: Nolan C (ed) Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor

Sieciechowicz KA, Joy KW, Ireland RJ (1988) The metabolism of asparagine in plants. Phytochemistry 27:663–671

Sodek L, Lea PJ, Miflin DJ (1980) Distribution and properties of a potassium-dependent asparaginase isolated from developing seeds of Pisum sativum and other plants. Plant Physiol 65:22–26

Wriston JC Jr, Yellin TO (1973) l-Asparaginase: a review. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol 39:185–248

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Oza, V.P., Parmar, P.P., Patel, D.H. et al. Cloning, expression and characterization of l-asparaginase from Withania somnifera L. for large scale production. 3 Biotech 1, 21–26 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-011-0003-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-011-0003-y