Abstract

Introduction

To evaluate the clinical impact of a comprehensive care bundle for the management of candidemia.

Methods

A quasi-experimental pre-post study was implemented. During the pre-intervention period (May 2014–September 2015), a non-mandatory antifungal stewardship program (ASP) was implemented, and patients with candidemia were visited by an infectious disease specialist who provided diagnostic and therapeutic advice according to standard of care as soon as possible. During the post-intervention period (October 2015–May 2017), patients were managed according to a candidemia care bundle with clear and structured recommendations written in their medical history.

Results

Overall, 109 patients were included, 56 in the pre-intervention and 53 in the post-intervention period. Overall, compliance with the Candida bundle significantly improved between the pre- [27/56 (48.2%)] and post-intervention [43/53 (81.1%); p = 0.01] period. Individual bundle components that significantly improved in the post-intervention period were early adequate antifungal therapy [47/56 (83.9%) vs. 51/53 (96.2%), p = 0.05], early adequate source control of the infection [37/56 (82.2%) vs. 41/53 (97.6%), p = 0.03] and appropriate duration of therapy [27/56 (48.2%) vs. 43/53 (81.1%), p = 0.01]. Adherence to follow-up blood cultures, ophthalmologic examination and echocardiography improved in the post-intervention period, but the difference was not statistically significant. Multivariate analysis revealed that being managed according to candidemia bundle had a favorable impact on 14-day mortality (HR 0.08, 95% CI 0.01–0.45, p = 0.02) and 30-day mortality (HR 0.40, 95% CI 0.18–0.89, p = 0.02).

Conclusions

A simple bundle focused on increasing adherence to a few evidence-based interventions contributed to a significant reduction in 14- and 30-day mortality in patients with candidemia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Candida bloodstream infection (BSI) is a life-threating disease associated with significant morbidity, mortality and high healthcare costs. |

Prompt diagnosis, early administration of appropriate therapy and adequate source control of infection have been shown to improve the prognosis. |

Our hypothesis was that the systematic implementation of structured recommendations aimed at enhancing adherence to evidence-based indicators could improve both diagnostic procedures and antifungal therapy and eventually the outcome of patients with candidemia. |

A simple bundle focused on increasing adherence to a few evidence-based interventions contributed to a significant reduction in 14- and 30-day mortality in patients with candidemia. |

Introduction

Candida bloodstream infection (BSI) is a life-threating disease associated with significant morbidity, mortality and high healthcare costs. Complications are frequent [1, 2], and mortality ranges between 20 and 45% [3,4,5].

Prompt diagnosis, early administration of appropriate antifungal therapy and adequate source control of infection have been shown to be key factors that improve the prognosis of patients with candidemia [6,7,8,9,10]. Infectious disease (ID) consultations providing diagnostic and therapeutic bedside recommendations as a part of antifungal stewardship programs (ASP) have also been demonstrated to be associated with a better prognosis for candidemic patients [11,12,13].

However, the recommendations provided by the ID consultants in such studies were not structured according to a bundle approach, and specific interventions were not always completed in time.

Our hypothesis was that the systematic implementation of structured recommendations aimed at enhancing adherence to evidence-based indicators could improve both diagnostic procedures and antifungal therapy and eventually the outcome of patients with candidemia. Therefore, the aim of this prospective study was to evaluate the all-cause 14- and 30-day mortality in candidemic patients before and after the implementation of a bedside checklist care bundle in our antifungal stewardship program.

Methods

Study Setting

This study was performed at the Hospital Universitario General Gregorio Marañón, a 1550-bed tertiary care institution in Madrid, with a full range of clinical services attending a population of approximately 715,000 inhabitants.

Study Population

All consecutive adult patients (> 18 years of age) with at least one episode of candidemia diagnosed over the May 2014 to May 2017 period were eligible for the study. Exclusion criteria were: patients with a life expectancy of < 72 h or those who were transferred to another healthcare facility.

Study Design

We performed a pre-post quasi-experimental study. During the pre-intervention period (May 2014–September 2015), a non-mandatory ASP was implemented at our hospital [12], and patients with candidemia were visited by an ID specialist who provided diagnostic and therapeutic advice according to standard of care as soon as possible.

During the post-intervention period (October 2015–May 2017), patients were managed according to a candidemia care bundle. Briefly, two ID physicians with specific expertise in mycology and antifungal therapy followed all candidemic patients and actively promoted adherence to bundle endpoints providing clear and structured recommendations that were written in the patients' medical history. In particular, ID physicians performed follow-up visits of all candidemic patients to (1) review antifungal therapy and change it according to culture results and (2) request (based on the checklist) follow-up blood cultures, ophthalmologic examination or echocardiography. In addition to visits scheduled according to the study protocol (Table 1), further clinical assessments were also performed according to patients' clinical need. Patients were followed up until 30 days from Candida BSI onset or until death.

Intervention

The care bundle and quality “indicators” were extracted after having reviewed and collectively discussed the best practice advances in the management of candidemia [10]. The quality indicators were required to adhere to the following criteria: (1) the indicators are generally accepted clinical practice and supported by evidence; (2) the completion of each indicator can be determined by a yes or no on the checklist.

Six recommendations were therefore included in our care bundle for candidemia. Each one was provided in a structured form and checked on a list. Bundle endpoints included: (1) early (< 72 h) adequate antifungal therapy, (2) early (< 72 h) source control, if necessary, (3) follow-up blood cultures, (4) ophthalmologic examination, (5) echocardiogram and (6) adequate duration of therapy according to the complexity of the infection. Additionally, we also included a standardized checklist to gather bundle compliance data and to periodically check the clinical condition of the patients, microbiologic culture results and compliance with other measures that are generally accepted good clinical practice, such as drug selection and drug dosing according to hepatic and renal function, drug-drug interactions and drug de-escalations (Table 1).

The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Maranon (MICRO.HGUGM.2015-068) and was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from each participating patient.

Endpoints

Considering that among patients with candidemia 30-day mortality is mainly related to the underlying disease of the patients [9], and assuming that an adequate management of candidemia could have an impact on 14-day related mortality, the main outcome of our study was 14-day all-cause mortality. As secondary outcome, we considered the adherence to all the quality indicators of the Candida bundle and 30-day mortality rate.

Definitions

An episode of candidemia was defined as a patient that had at least one peripheral blood culture positive for Candida species. Sepsis, severe sepsis or septic shock were recorded on the day of candidemia [14]. Pitt’s bacteremia score was defined according to the standard international criteria [15].

As for the source of infection, an episode of candidemia was considered catheter-related if (1) the catheter tip culture was positive with the same Candida species, (2) there was evidence of exit site catheter exudate with the same Candida species or (3) the differential time to positivity of BCs obtained from the catheter and peripheral veins was ≥ 2 h [16].

The urinary tract was considered the portal of entry in patients with urologic predisposing conditions (i.e., manipulation or obstruction of the urinary tract) and evidence of urinary tract infection caused by the same species of Candida.

The abdomen was considered to be the origin of the candidemia when a patient had evidence of abdominal infection and (1) a positive culture from the intra-abdominal space was obtained during surgery or by needle aspiration and/or (2) no other apparent sources of candidemia were detected. When a source of candidemia could not be identified, candidemia was defined as “primary”.

Patients were considered to have Candida septic metastasis when an infection due to the same Candida species occurred in a site that was distant from the source of the candidemia. In cases in which no culture was available, the distant infection had to be temporally related with the fungemia and with no alternative cause explaining the clinical condition.

Infective endocarditis was diagnosed according to the Duke criteria [17]; ocular candidiasis was classified based on previous criteria [2, 5]; septic thrombophlebitis required the presence of venous thrombosis, confirmed by imaging techniques, in the setting of persistent candidemia [10].

Early antifungal treatment was defined as adequate if a recommended dose of an antifungal drug was administered within 72 h after candidemia onset, and it was found to be effective by in vitro susceptibility testing. Early adequate source control was defined as removal of the indwelling catheter or surgical drainage of deep infection within 72 h after the index blood sample had been drawn. For patients with candidemia without metastatic infection, duration of antifungal therapy was considered adequate when it lasted at least 14 days from the first negative blood cultures. For patients with candidemia with metastatic infection (i.e., ocular candidiasis, lung metastasis) and/or other complications (i.e., thrombophlebitis), duration of treatment was considered adequate when it reached at least 4–6 weeks or even longer in case of infective endocarditis.

Data Collection

Data were prospectively recorded on a standardized case report form that included demographics, comorbidities, predisposing risk factors within the preceding 30 days, clinical severity according to the Pitt score, source of the infection, adherence to the Candida bundle, clinical management of the patients including antifungal choice, length of therapy and adequate source control of the infection and all-cause mortality.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data. Quantitative variables are reported as median and interquartile range (IQR) and categorical variables as counts (%). The chi-square test or Fisher exact tests were used to compare the distribution of categorical variables, including the clinical characteristics of the pre- and post-intervention period and the association between individual risk factors and mortality rate. The t-test or Mann-Whitney test was used to compare quantitative variables. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The Kaplan-Meier curve was constructed to show the relationship between the intervention strategy and 14-day survival. The statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft SPSS PC+, version 15.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

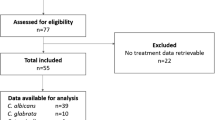

The flowchart study is shown in Fig. 1. Overall, 147 patients were diagnosed with an episode of candidemia, 73 in the pre-intervention and 74 in the post-intervention period. In the pre-intervention period, ten patients were excluded because they were aged < 18 years, and six died within the first 72 h; one patient was transferred to another hospital. In the post-interventional period, 13 patients were excluded because they were aged < 18 years, 4 declined participation, 3 died within the first 72 h, and 1 was transferred to another healthcare facility.

The demographics and clinical features of the 109 patients in the study populations are shown in Table 2. Mean age was 67.2 years, and 73/109 patients were males (67.0%). The most common underlying condition was solid tumor [60/109 (55.0%)] followed by gastrointestinal disease [44/109 (40.7%)]. A central venous catheter (CVC) was in place in 86/109 patients (78.9%), and 70/109 (64.2%) were receiving total parenteral nutrition at the time of their episode. The most prevalent source of infection was the CVC [65/109 (59.6%)] followed by intra-abdominal origin [18/109; (16.5%)]. Only 13/109 patients (11.9%) had a primary infection.

Comparison Between the Pre- and Post-intervention Period

The main demographic characteristic and risk factors for candidemia in the pre- and post-intervention period are compared in Table 2. Both populations were similar, and no statistically significant differences were detected regarding the demographics, underlying diseases, risk factors for candidemia, severity of disease and Candida species. However, in the pre-intervention period, patients had an intra-abdominal origin more often than those in the post-intervention period [12/56 (21.4%) vs. 6/53 (11.3%)], but this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.20). During the pre-intervention period, ID physicians visited patients in 50/56 cases (89.2%), whereas 53/53 patients (100%) were visited in the post-intervention period (p = 0.71).

Overall, compliance with the Candida bundle significantly improved between pre- [27/56 (48.2%)] and post-intervention [43/53 (81.1%); p = 0.01] period (Table 3). Individual bundle components that significantly improved in the post-intervention period were early adequate antifungal therapy [47/56 (83.9%) vs. 51/53 (96.2%), p = 0.05], early adequate source control of the infection [37/56 (82.2%) vs. 41/53 (97.6%), p = 0.03] and appropriate duration of therapy [27/56 (48.2%) vs. 43/53 (81.1%), p = 0.01]. Moreover, adherence to follow-up blood cultures, ophthalmologic examination and echocardiography improved in the post-intervention period, but the difference was not statistically significant.

Analysis of All-cause Mortality at 14 and 30 Days

Overall, all-cause mortality at 14 and 30 days was 14.9% (16/109) and 27.5% (30/109). Variables associated with 14- and 30-day mortality in the univariate analyses are summarized in Tables 4 and Table 5. Being managed according to the candidemia bundle had a favorable impact on 14-day mortality [50/93 (53.8%) versus 3/16 (18.8%), p = 0.01] but not on the 30-day mortality rate [41/79 (51.9%) versus 12/30 (40%), p = 0.29]. However, after controlling for baseline characteristics, clinical presentation of candidemia and source of infection, being managed according to the candidemia bundle remained the only variable independently associated with a decreased all-cause mortality at both 14 (HR 0.08, 95% CI 0.01–0.45, p = 0.02) and 30 days (HR 0.40, 95% CI 0.18–0.89, p = 0.02) (Table 6).

Discussion

Our study shows that the combination of a comprehensive candidemia bundle with antifungal stewardship program involvement significantly improves adherence to guideline recommendations and overall management of patients with candidemia. This novel approach was effective and resulted in a reduction in 14- and 30-day all-cause mortality in the post-intervention group.

To our knowledge, this study is one of the largest and most inclusive study evaluating the clinical impact of a checklist care bundle for management of patients with candidemia. However, many published studies have described individual aspects of the bundle being associated with better prognosis (i.e., early adequate antifungal administration or adequate source control) [6,7,8,9]; only three recent studies have addressed the impact of a bundle approach on the management of patients with candidemia [18,19,20]. Antworth et al. [18] conducted a single-center study of 78 patients with candidemia and demonstrated improved compliance with all candidemia care bundle elements, but not significant differences in clinical outcome.

Takesue and colleagues [19] performed a nationwide study of 608 patients with candidemia to investigate compliance with their bundle and its impact on mortality. Unfortunately, study participation by infection control doctors was entirely voluntary, and the candidemia bundle was not systematically implemented in all candidemic patients. Reflecting this weakness, compliance with all bundle elements was particularly poor (6.9%), and the correlation between bundle compliance and either clinical success or mortality was not observed.

Finally, Gouliorius et al. implemented a similar study design to ours, but lacked the sample size to detect significant differences in mortality [12/44 (27%) versus 3/33 (9%), p = 0.08] [20].

In our study, the overall compliance with quality indicators was significantly improved in the intervention group, mainly driven by improvements in the administration of early adequate antifungal therapy, early source control of infection and adequate length of antifungal therapy. Notably, the improvements were demonstrated in a clinical setting with long experience in an antifungal stewardship program [12, 21, 22], in which the comparatively pre-intervention adherence to recommendations was particularly high (80.4–89.3%). These results highlight the importance of candidemia bundle implementation even in institutions with high baseline adherence and not only in hospitals with low baseline rates of bundle adherence, where the impact of the intervention could be even better than ours.

Regarding this aspect, the current study is the first demonstrating how the systematic implementation of a candidemia bundle can be associated with decreased all-cause mortality. Although previous studies showed that infectious disease consultation was associated with better management and patient outcome [11,12,13], we surprisingly found that 89.2% of the patients in the pre-intervention period were visited by an infectious disease specialist. We believe that using a structured “checklist” for making recommendations was crucial for reminding the infectious disease specialists about all the key aspects to consider for the management of patients with candidemia.

It is important to mention that other reasons could explain the better evolution of patients treated according to our candidemia bundle. First, our bundle was unique in that we not only looked at the intervention of implementing a candidemia protocol, but also looked at multiple aspects in the process of care, including management of other concomitant infections, medication toxicity and drug-drug interactions. All these items could have contributed to better use of antifungal therapy, especially in a population with multiple comorbidities such as ours. Second, in our bundle we included “adequate source control of the infection” rather than the “simple” CVC withdrawal included in all earlier studies as a major recommendation [18,19,20]. As previously reported, the benefit of early CVC withdrawal might be disputable when the source of candidemia is not the catheter [23, 24]. Considering that 30–40% of candidemic patients had an origin other than CVC, the more restrictive definition of adequate source control used by Antworth, Takesue and Goulorius [18,19,20] may explain why their reports were not able to find a significant association between the bundle interventions and mortality.

Finally, in contrast to previous studies, we did not include “de-escalation to fluconazole” [20] or “step-down therapy” [19] as a care element of our bundle. Although these components may play a significant role in terms of length of hospitalization and costs, its role in terms of improvement of patient outcome could be limited. In our opinion, future studies should be performed to compare candidemia bundles to identify one that is easier to perform and associated with a better outcome.

This study has some limitations that should be assessed. First, it is a quasi-experimental pre-post study design that lacks randomization. Thus, we may not have taken changes in standard of care for patients with candidemia during the study periods into account. Second, being a single-center study, the external validity should be confirmed. To note that our study was performed in a tertiary university hospital with a long history of antifungal stewardship and ID consultations, where all colleagues (even those in specialties other than infectious disease, e.g., surgeons, ophthalmologists, cardiologists) are clearly aware of the severity of Candida BSI. Therefore, the impact of the intervention could be not fully reproducible in other facilities without an antifungal stewardship program or ID consultation service. However, the results of this approach, based on the early involvement of an ID specialist in the management of patients with candidemia, could lead other healthcare organizations to implement collaborations with ID specialists. Third, our outcome measure was all-cause mortality, and we did not report any data on Candida-attributable mortality or mycologic response.

Conclusion

In conclusion, according to our study hypothesis, the introduction of a comprehensive candidemia bundle with antifungal stewardship program involvement significantly improved adherence to quality indicators, overall management and clinical evolution of patients with candidemia. Our study encourages the systematic use of care bundles for the management of candidemia.

References

Fernandez-Cruz A, Cruz Menarguez M, Munoz P, et al. The search for endocarditis in patients with candidemia: a systematic recommendation for echocardiography? A prospective cohort. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34(8):1543–9.

Munoz P, Vena A, Padilla B, et al. No evidence of increased ocular involvement in candidemic patients initially treated with echinocandins. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;88(2):141–4.

Andes DR, Safdar N, Baddley JW, et al. Impact of treatment strategy on outcomes in patients with candidemia and other forms of invasive candidiasis: a patient-level quantitative review of randomized trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(8):1110–22.

Bassetti M, Peghin M, Carnelutti A, et al. Invasive candida infections in liver transplant recipients: clinical features and risk factors for mortality. Transpl Direct. 2017;3(5):e156.

Vena A, Munoz P, Padilla B, et al. Is routine ophthalmoscopy really necessary in candidemic patients? PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0183485.

Garey KW, Rege M, Pai MP, et al. Time to initiation of fluconazole therapy impacts mortality in patients with candidemia: a multi-institutional study. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(1):25–31.

Kollef M, Micek S, Hampton N, Doherty JA, Kumar A. Septic shock attributed to Candida infection: importance of empiric therapy and source control. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(12):1739–46.

Puig-Asensio M, Peman J, Zaragoza R, et al. Impact of therapeutic strategies on the prognosis of candidemia in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(6):1423–32.

Puig-Asensio M, Padilla B, Garnacho-Montero J, et al. Epidemiology and predictive factors for early and late mortality in Candida bloodstream infections: a population-based surveillance in Spain. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(4):O245–54.

Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(4):e1–50.

Farmakiotis D, Kyvernitakis A, Tarrand JJ, Kontoyiannis DP. Early initiation of appropriate treatment is associated with increased survival in cancer patients with Candida glabrata fungaemia: a potential benefit from infectious disease consultation. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(1):79–86.

Valerio M, Munoz P, Rodriguez CG, et al. Antifungal stewardship in a tertiary-care institution: a bedside intervention. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(5):492 e491-499.

Jones TM, Drew RH, Wilson DT, Sarubbi C, Anderson DJ. Impact of automatic infectious diseases consultation on the management of fungemia at a large academic medical center. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74(23):1997–2003.

Levy M, Fink MP, Marshall JC, et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Intensive Care Med. 2003;4:530–8.

Paterson DL, Ko WC, Von Gottberg A, et al. Antibiotic therapy for Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia: implications of production of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(1):31–7.

Mermel LA, Allon M, Bouza E, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(1):1–45.

Li JS, Sexton DJ, Mick N, et al. Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(4):633–8.

Antworth A, Collins CD, Kunapuli A, et al. Impact of an antimicrobial stewardship program comprehensive care bundle on management of candidemia. Pharmacotherapy. 2013;33(2):137–43.

Takesue Y, Ueda T, Mikamo H, et al. Management bundles for candidaemia: the impact of compliance on clinical outcomes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70(2):587–93.

Gouliouris T, Micallef C, Yang H, Aliyu SH, Kildonaviciute K, Enoch DA. Impact of a candidaemia care bundle on patient care at a large teaching hospital in England. J Infect. 2016;72(4):501–3.

Valerio M, Munoz P, Rodriguez-Gonzalez C, et al. Training should be the first step toward an antifungal stewardship program. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2015;33(4):221–7.

Valerio M, Rodriguez-Gonzalez CG, Munoz P, et al. Evaluation of antifungal use in a tertiary care institution: antifungal stewardship urgently needed. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(7):1993–9.

Garnacho-Montero J, Diaz-Martin A, Garcia-Cabrera E, Ruiz Perez de Pipaon M, Hernandez-Caballero C, Lepe-Jimenez JA. Impact on hospital mortality of catheter removal and adequate antifungal therapy in Candida spp. bloodstream infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(1):206–13.

Nucci M, Anaissie E, Betts RF, et al. Early removal of central venous catheter in patients with candidemia does not improve outcome: analysis of 842 patients from 2 randomized clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(3):295–303.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all members of the Collaborative Study Group of Mycology (COMIC): Emilio Bouza, Patricia Munoz, Pilar Escribano, Maricela Valerio, Ana Fernandez Cruz, Paloma Gijon, Belen Padilla, Carlos Sanchez, Roberto Alonso, Jesus Guinea, Antonio Vena, Marina Machado, Marıa Olmedo, Almudena Burillo, Marıa Sanjurjo, Carmen Rodrıguez, Mamen Martınez, Mi Kown, Gabriela Rodrıguez-Macıas, Jorge Gayoso, Miguel Martın, Rafa Banares, Fernando Anaya, Marisa Rodr ~ ıguez, Manuel Martınez Selles, Eduardo Zarataın, Magdalena Salcedo, Diego Rincon, Javier Hortal, Lorenzo Fernandez Quero, Jose ´ Eugenio Guerrero, Jose´ Peral, Jose´ Marıa Tellado, Javier Garcıa, Manuel Sanchez Luna, Amaya Bustinza, Elena Zamora, Teresa Hernandez Sampelayo, Marisa Navarro, Isabel Frıas Soriano, Marta Grande, Lola Vigil, Jesus Torre, Nerea Alava, Javier Alarcon, Marisa Alegre, Ana Cabrero, Ana Pulido and Veronica Parra.

Funding

This study was partially financed by the PROgrama MULtidisciplinar para la Gestión de Antifúngicos y la Reducción de Candidiasis Invasora (PROMULGA) II Project, Instituto de Salud Carlos III Madrid, Spain, partially financed by the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER) “A way of making Europe” (grant no. PI13/01148). Antonio Vena is supported by a Rio Hortega from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III Madrid, Spain, partially financed by the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER) “A way of making Europe” (grant no. CM15/00181). No funding or sponsorship was received for the publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Patricia Munoz is a consultant and/or speaker for Astellas, Gilead, Merck, Novartis and Pfizer and T2 Biosystems. Antonio Vena now is at the “Department of Health Sciences, Infectious Disease Clinic, University of Genoa and Hospital Policlinico San Martino-IRCCS, Genoa, Italy.” Emilio Bouza, Rafael Corisco, Marina Machado, Maricela Valerio and Carlos Sánchez have nothing to declare.

Compliance with Ethical Guidelines

The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Maranon (MICRO.HGUGM.2015-068) and was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from each participating patient.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced digital features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11550204.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vena, A., Bouza, E., Corisco, R. et al. Efficacy of a “Checklist” Intervention Bundle on the Clinical Outcome of Patients with Candida Bloodstream Infections: A Quasi-Experimental Pre-Post Study. Infect Dis Ther 9, 119–135 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-020-00281-x

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-020-00281-x