Abstract

Background

Aerobic training (AT) and Turmeric Supplementation (TS) are known to exert multiple beneficial effects including metabolic status and Oxidative Stress. To our knowledge, data on the effects of AT and TS on metabolic status and oxidative stress biomarkers related to inflammation in subjects with Hyperlipidemic Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (HT2DM) are scarce.

Objectives

This study was conducted to evaluate the effects of AT and TS on metabolic status and oxidative stress biomarkers related to inflammation in subjects with HT2DM.

Methods

This randomized single-blinded, placebo-controlled trial was conducted among 42 subjects with HT2DM, aged 45–60 years old. Participants were randomly assigned to four groups; AT+TS (n = 11), AT+placebo (AT; n = 10), TS (n = 11), and Control+placebo (C; n = 10). The AT program consisted of 60–75% of Maximum heart rate (HRmax), 20–40 min/day, three days/week for eight weeks. The participants in the TS group consumed three 700 mg capsules/day containing turmeric powder for eight weeks. Metabolic status and oxidative stress biomarkers were assessed at baseline and end of treatment. The data were analyzed through paired t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Bonferroni post hoc test at the signification level of P < 0.05.

Results

After eight weeks, significant improvements were observed in metabolic status, oxidative stress biomarkers and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) in the AT+TS, TS, and AT compared to C. Additionally, a significant decrease of Metabolic Syndrome (MetS) Z scores (p = 0.001; p = 0.011), hs-CRP (p = 0.028; p = 0.041), Malondialdehyde (MAD) (p = 0.023; p = 0.001), and significantly higher Glutathione (GSH) (p = 0.003; p = 0.001), and Total Antioxidant Capacity (TAC) (p = 0.001; p = 0.001) compared to the AT and TS groups. The results also revealed a significant difference in terms of MetS Z scores (p = 0.001), hs-CRP (p = 0.018), MAD (p = 0.011), GSH (p = 0.001) and TAC (p = 0.025) between the AT and TS.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that AT+TS improves metabolic status, oxidative stress biomarkers, and hs-CRP more effectively compared to TS or AT in middle-aged females with T2DM and hyperlipidemia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) is a primary cause of mortality in both men and women, leading to over 7 million deaths each year [1]. It is widely accepted that Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) is also one of the important risk factors for CHD. The risk of CHD in patients with Hyperlipidemic T2DM (HT2DM) is doubled high than in non-diabetic patients [2]. Several studies showed a correlation between HT2DM, CHD, and metabolic syndrome (MetS) with elevated oxidative stress biomarkers and high-sensitivity C-Reactive Protein (hs-CRP) (3,4). Lifestyle changes (i.e., supplementation and exercise) are among the complementary therapeutic approaches in patients with HT2DM [1]. Convincing evidence showed that Aerobic Training (AT) has the potential to enhance weight loss, increase the Glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) abundance, and improve metabolic status in these patients [2, 3]. Turmeric, with the scientific name of Curcuma longa, is used in traditional Chinese medicine [4] that contains polyphenols, flavonoids, and tannins and is proposed to have anti-diabetic properties [5,6,7]. Turmeric Supplementation (TS), probably via improving Total Antioxidant Capacity (TAC) [8] and hs-CRP, plays an inhibitory role in the development of inflammation in different disease conditions [9]. Additionally, the basis of biological disorders in individuals with HT2DM is the development of inflammatory mediators [5, 10]. The results of studies on patients with HT2DM indicated significantly reduced malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, Fasting Blood Glucose (FBG), and improved metabolic status following TS [11, 12]. Various literature focused on the separate effects of both AT and TS in patients with HT2DM. While, scant studies so far have evaluated the effects of combined AT and TS, and none has compared the separate and interactional effects of AT and TS. Given the risk of exercising in sports facilities during the COVID-19 outbreak, this study aimed to evaluate the effects of combined AT and TS on metabolic status and oxidative stress biomarkers in HT2DM patients.

Methods

Participants and trial design

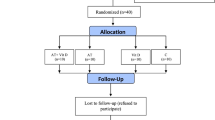

This is a single-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study that was performed in May–July 2021. The sample size was estimated at 36 using G. POWER 3.1 software (power = .99, alpha = 0.05, and effect size = 0.85), but we selected 44 middle-aged (40–60 years) women with HT2DM from the Diabetes Center of Taleghani Hospital, Kermanshah to be more conservative. Then, they were randomly assigned to: AT+TS (n = 11), AT+placebo (AT; n = 11), TS (n = 11), and control+placebo (C; n = 11). All participants had the same chance of being selected and divided into groups using a numbered list and a Random Number Generator. One participant in AT and one in C refused to continue the research (Fig. 1). The inclusion criteria included; diagnosed HT2DM, FBG > 126, Triglycerides (TG) >150 mg/dL, and 25 ≤ BMI < 30 kg/m2 [13]. The exclusion criteria included; being infected with COVID-19 during the study period, regular exercise schedule, history of orthopedic disorders, muscle injuries, smoking, consumption of immunosuppressive drugs, antioxidants, and multivitamin supplements, within the past three months, irregular attendance in the study protocol, and the test sessions, and inability to perform the exercises.

Aerobic training

The participants of AT+TS and AT groups were required to exercise for eight weeks. All training sessions were supervised by exercise physiologists.

Based on the American Diabetes Association (ADA) guidelines [14], the exercise program consisted of three days of AT per week started at 60% of Maximum heart rate (HRmax) and 20 min per session and gradually 75% of HRmax and 40 min (Table 1). Ten minutes warm-up and a Ten minutes cool-down were also executed each session. We used the HRmax formula [HRmax = 220 − age] to determine the target heart rate at the outset [15]. The participants were taught the pulse palpation method to count their heart rate in the training session. Furthermore, to assure achieving and maintaining the desired heart rate (exercise intensity) during the AT phase, a 6–20 Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale was also used (Table 1) [16].

Turmeric supplement

The participants were requested to consume the same amounts of food and macronutrient composition one day before blood sampling both at the pre-test and post-test. Using the results of the previous studies, the AT+TS and TS groups were given three capsules/day containing 700 mg (a total of 2100 mg per day) of turmeric powder with main meals for eight weeks [17]. The turmeric powder was prepared in Dineh Pharmaceutical Company, Iran. Meanwhile, C and AT consumed placebo capsules containing cornstarch flour with similar color, shape, and taste.

Measurements

The participants got acquainted with the study procedure three days before the intervention. The participants were asked to avoid participating in intensive physical activities and taking diuretics 48 h before the test. Then, height to the nearest 0.5 cm using a stadiometer (DETECTO, Model 3PHTROD-WM, USA); Waist Circumference (WC) to the nearest 0.5 cm with a non-elastic tape measure; and bodyweight by the INBODY test using bioelectric impedance analysis (Zeus 9.9 PLUS; Jawon Medical Co., Ltd., Kungsang Bukdo, South Korea) were measured at the beginning and the end of the study at 8–9 A.M. after an at least 12-h fasting.

Systolic Blood Pressure (SBP) and Diastolic Blood Pressure (DBP) were measured using a standard mercury sphygmomanometer (Missouri) and stethoscope (Rappaport GF Health Products, Northeast Parkway Atlanta) by the same person. The appearance of Korotkoff sounds was considered as SBP while DBP was determined at the disappearance point of these sounds.

Blood sampling

Twenty cc of antecubital vein blood was sampled using an anticoagulant-treated syringe, 48 h before the first (pre-test) and after the last training sessions (post-test) in a 12-h fasting condition. Then the samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 3000 rpm using a centrifugal separator, the serum was extracted from the cellular components, poured into a storage tube, and stored at −70 °C until analysis. TG and High-Density Lipoprotein (HDL) were measured using Hitachi kits (Tokyo, Japan) enzymatically. Besides, FBG via the enzymatic method (Pars Azmun Kit, Iran), hs-CRP levels via ELISA method (LDN; DM E-4600 Tags code, Nordhorn: Germany; inter-assay and intra-assay CVs below 7%.) [18], TAC via Benzie and Strain [19] technique (inter-assay and intraassay CVs lower than 5%.), Glutathione (GSH) via the procedure described by Beutler et al. [20], and MDA by a spectrophotometric method [21] (inter-assay and intra-assay CVs lower than 5%). The results of MetS components including WC, fasting glucose, SBP, HDL, cholesterol, and TG were used to compute MetS z score (via http://mets.health-outcomes-policy.ufl.edu/calculator/) [22].

Data analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS software, version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). All the data have been presented as mean and standard deviation. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to check the normal distribution of the continuous variables. Between-group comparisons were made using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Bonferroni post hoc test. Within-group comparisons were also made using paired sample t-test. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Table 2a shows the between-group comparisons of metabolic status (WC, FBG, TG, HDL, SBP, and DBP) among participants. Based on the results of the t-test there are significant differences in the means of (WC, FBG, TG, HDL, SBP, and DBP) in the post-test compared to the pre-test. After eight weeks, WC, FBG, TG, SBP, and DBP significantly decreased and HDL significantly increased in the AT+TS, AT, and TS, however in the C these alterations were reversed.

The results of ANOVA revealed significant differences among the study groups regarding metabolic status. The results of the Bonferroni post hoc test showed that WC, FBG, TG, HDL, SBP, and DBP changes were significant in the AT+TS, AT, and TS groups compared to the C group. The results indicate significant differences between AT+TS compared to AT and TS groups; lower WC, FBG, TG, SBP, and DBP, but higher HDL. The results also showed a significantly lower WC, FBG, TG, SBP, and DBP in AT compared to TS however, HDL was not significantly different (p = 0.440) (Table 2b).

The results of ANOVA revealed significant differences among the study groups regarding MetS Z scores. The results of the Bonferroni post-hoc test showed that the MetS Z score was significantly lower in the AT+TS (p = 0.001), AT (p = 0.001), and TS (p = 0.001) groups compared to the C group. The MetS Z score was significantly lower in AT+TS compared to AT (p = 0.023), and TS (p = 0.001). The results also showed significantly lower MetS Z scores in AT compared to TS (p = 0.023) (Fig. 2).

As detailed in Table 2b, the results revealed a significant improvement in MDA, GSH, TAC, and hs-CRP in AT+TS, AT, and TS comparing the pretest to the posttest. Additionally, the results of ANOVA show significant differences among the study groups concerning MDA, GSH, TAC, and hs-CRP. Accordingly, a significant difference was found between the AT+ST, AT, and TS groups and the C group regarding MDA, GSH, TAC, and hs-CRP. Besides, the AT+TS group had significantly lower MDA (p = 0.001; p = 0.001), and hs-CRP (p = 0.028; p = 0.041) and significantly higher GSH (p = 0.003; p = 0.001), and TAC (p = 0.001; p = 0.001) compared to the AT and TS; respectively. Furthermore, significantly lower MDA (p = 0.011) and hs-CRP and significantly higher (p = 0.018) GSH (p = 0.001) and TAC (p = 0.025) were observed compared to TS.

Discussion

The results of the present study indicated that eight weeks of intervention improved metabolic status in females with HT2DM; although this improvement was significant in the AT and TS, it was significantly higher in the AT+TS. However, a significant increase was found in the metabolic status in C. In the same line, Bacchi et al. (2012) Saghebjoo et al. (2018) [23], and Jiang et al. (2020) [24] stated that reported that resistance training, similarly to AT, improves metabolic status, anthropometric indices, and insulin sensitivity in T2DM patients. [25]. Consistent with the results of the present study, Adab et al. (2019) reported that the daily consumption of 2100 mg of turmeric powder (700 mg capsules) resulted in a significant improvement in body measurement indices, glycemic condition, and lipid profile in patients with HT2DM [26]. Ho et al. (2012) also assessed the anti-obesity effects of turmeric in obese rats and revealed a significant reduction in weight [27].

Eight weeks of combined AT+TS has been associated with improved MetS z score in females with HT2DM. Hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, and hypertriglyceridemia via disturbing the glycation of lipoproteins and a lot of other unfavorable effects accelerate HT2DM [28]. AT however affects the insulin secretion, transduction of insulin receptor signals, and inhibition of protein tyrosine phosphatases [29]. AT plays an important role in stabilizing the insulin via increasing phosphorylated β subunit of the insulin receptor that enhances the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase and protein kinase B (PKB or Akt) which in turn enables the GLUT4 translocation and glucose transport into the cells [29]. TS, as a crucial cofactor modulating hydroxymethylglutaryl (HMG)-CoA reductase enzyme and enzymatic processes requiring adenosine triphosphate, also has a pivotal role in glucose and lipoprotein metabolism [30].

The results of the current study showed significant changes in the oxidative stress biomarker in AT, TS, and AT+TS including downregulated hs-CRP and MAD, and upregulated GSH and TAC in favor of AT+TS after eight weeks. Improved oxidative stress biomarkers following AT is well known as observed in our study, however, the underlying mechanisms need to be elucidated [31,32,33].

Several studies show that the protective effect of longer-term AT on oxidative stress might, to some extent, be ascribed to reduce chronic inflammation which is also associated with a negative energy balance [34]. Data in pathological conditions, such as HT2DM, have highlighted the idea that AT can decrease inflammatory and/or increase anti-inflammatory cytokines levels [32]. Increased pro-inflammatory cytokines and CRP have also been reported by de Lemos et al., demonstrating the anti-inflammatory capacity of AT in diabetic ZDF rats [35, 36]. Furthermore, AT improve the inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers by enhancing skeletal muscle and adipose tissue [37,38,39], as endocrine tissues, expressing both Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase and adipokines/myokines [40, 41].

TS develops antidiabetic properties via various mechanisms of action including inhibiting α-amylase and α-glucosidase enzymes, insulin secretion, and reducing oxidative stress that the latter was also observed in this study [7]. Also, TS is believed to inhibit nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells activation, decrease intercellular adhesion molecule, cyclooxygenase-2, and Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, and reduce intrahepatic monocyte chemoattracting protein-1gene, CD11b, procollagen type I, and tissue metalloproteinase inhibitor expression which in turn reduce oxidative stress and improve inflammation [7, 42, 43]. Moreover, TS affects adiposity and lipid metabolism by modulating energy metabolism and inflammation [44]. Additionally, TS is shown to have hypocholesterolemic properties [45, 46]; reducing plasma TG and cholesterol [47].

The strengths of the present study were the successful blinding of the participants, accurate control of AT intensity, and a high rate of compliance (all the participants reported that they had taken capsules through the study). However, one of the study’s limitations was that it was a short-term trial, and it is unknown whether longer durations of supplementation could cause further improvements. Additionally, the impact of different doses was not investigated in this research. Finally, the small number of participants could affect the generalizability of the results.

Conclusion

Based on the findings, AT+TS is recommended as a convincing lifestyle approach due to its great effect on metabolic status, oxidative stress biomarkers, and CRP in middle-aged females with T2DM. Yet, further studies are suggested to determine the most efficient TS dose and exercise type (High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT), Moderate Intensity Continuous Training (MICT), and Low-Intensity Continuous Training (LICT)) in different age groups in the long run.

Data availability

Any data will be available from the first author and corresponding upon request.

References

Khademi Z, Imani E, Heidary Khormizi M, Poordad Khodaei A, Sarneyzadeh M, Nikparvar M. A study on the variation of medicinal plants used for controlling blood sugar and causes of self–medication by patients referred to Bandarabbas diabetic center. J Diabetes Nurs. 2013;1(1):12–20.

Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Fernhall B, Regensteiner JG, Blissmer BJ, Rubin RR, et al. Exercise and type 2 diabetes: the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Diabetes Association: joint position statement. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(12):e147–e67.

Ghalavand A, Shakeriyan S, Monazamnezhad A, Dadvar N, Heidarnezhad M, Delaramnasab M. The effects of aerobic training on blood glycemic control and plasma lipid profile in men with type 2 diabetes. Sylwan. 2014;158(6):1–10.

Grintsov Y, Fedosov A, Moroz V, Timchenko Y, Shalamay A. Prospects of application of the complex with artichoke and garlic in clinical medicine. Klìnìčna Farmacìâ. 2017;21(3):11–20.

Sharma S, Kulkarni SK, Chopra K. Curcumin, the active principle of turmeric (Curcuma longa), ameliorates diabetic nephropathy in rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2006;33(10):940–5.

Soleimani V, Sahebkar A, Hosseinzadeh H. Turmeric (Curcuma longa) and its major constituent (curcumin) as nontoxic and safe substances. Phytother Res. 2018;32(6):985–95.

Ardalani H, Hejazi Amiri F, Hadipanah A, Kongstad KT. Potential antidiabetic phytochemicals in plant roots: a review of in vivo studies. J Diabetes Metabol Disord. 2021:1–18.

Duncan GE, Perri MG, Theriaque DW, Hutson AD, Eckel RH, Stacpoole PW. Exercise training, without weight loss, increases insulin sensitivity and postheparin plasma lipase activity in previously sedentary adults. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(3):557–62.

Saeedi-Boroujeni A, Mahmoudian-Sani MR, Bahadoram M, Alghasi A. COVID-19: A case for inhibiting NLRP3 Inflammasome, suppression of inflammation with curcumin? Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2021;128(1):37–45.

Zou J, Zhang S, Li P, Zheng X, Feng D. Supplementation with curcumin inhibits intestinal cholesterol absorption and prevents atherosclerosis in high-fat diet–fed apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Nutr Res. 2018;56:32–40.

Mokhtari M, Razzaghi R, Momen-Heravi M. The effects of curcumin intake on wound healing and metabolic status in patients with diabetic foot ulcer: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Phytother Res. 2021;35(4):2099–107.

Wang S-Q, Li D, Yuan Y. Long-term moderate intensity exercise alleviates myocardial fibrosis in type 2 diabetic rats via inhibitions of oxidative stress and TGF-β1/Smad pathway. J Physiol Sci. 2019;69(6):861–73.

Golabi P, Otgonsuren M, de Avila L, Sayiner M, Rafiq N, Younossi ZM. Components of metabolic syndrome increase the risk of mortality in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Medicine. 2018;97(13)

Aylin K, Arzu D, Sabri S, Handan TE, Ridvan A. The effect of combined resistance and home-based walking exercise in type 2 diabetes patients. Int J Diabetes Develop Countries. 2009;29(4):159.

Branco BHM, de Oliveira MF, Ladeia GF, Bertolini SMMG, Badilla PV, Andreato LV. Maximum heart rate predicted by formulas versus values obtained in graded exercise tests in Brazilian jiu-jitsu athletes. Sport Sci Health. 2020;16(1):39–45.

Rahimi E. Physical activity and type 2 diabetes: A narrative review. J Physical Activity Hormones. 2019;2(4):51–62.

Khajehdehi P, Zanjaninejad B, Aflaki E, Nazarinia M, Azad F, Malekmakan L, et al. Oral supplementation of turmeric decreases proteinuria, hematuria, and systolic blood pressure in patients suffering from relapsing or refractory lupus nephritis: a randomized and placebo-controlled study. J Ren Nutr. 2012;22(1):50–7.

Tatsch E, Bochi GV, da Silva PR, Kober H, Agertt VA, de Campos MMA, et al. A simple and inexpensive automated technique for measurement of serum nitrite/nitrate. Clin Biochem. 2011;44(4):348–50.

Hsieh C, Rajashekaraiah V. Ferric reducing ability of plasma: a potential oxidative stress marker in stored plasma. Acta Haematol Pol. 2021;52(1):61–7.

Beutler E, Gelbart T. Plasma glutathione in health and in patients with malignant disease. J Lab Clin Med. 1985;105(5):581–4.

Janero DR. Malondialdehyde and thiobarbituric acid-reactivity as diagnostic indices of lipid peroxidation and peroxidative tissue injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 1990;9(6):515–40.

Arazi H, Asadi A, Purabed M. Physiological and psychophysical responses to listening to music during warm-up and circuit-type resistance exercise in strength trained men. J Sports Med. 2015;2015

Saghebjoo M, Nezamdoost Z, Ahmadabadi F, Saffari I, Hamidi A. The effect of 12 weeks of aerobic training on serum levels high sensitivity C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, lipid profile and anthropometric characteristics in middle-age women patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metabol Syndrome: Clin Res Rev. 2018;12(2):163–8.

Jiang Y, Tan S, Wang Z, Guo Z, Li Q, Wang J. Aerobic exercise training at maximal fat oxidation intensity improves body composition, glycemic control, and physical capacity in older people with type 2 diabetes. J Exer Sci Fitness. 2020;18(1):7–13.

Bacchi E, Negri C, Zanolin ME, Milanese C, Faccioli N, Trombetta M, et al. Metabolic effects of aerobic training and resistance training in type 2 diabetic subjects: a randomized controlled trial (the RAED2 study). Diabetes Care. 2012;35(4):676–82.

Adab Z, Eghtesadi S, Vafa MR, Heydari I, Shojaii A, Haqqani H, et al. Effect of turmeric on glycemic status, lipid profile, hs-CRP, and total antioxidant capacity in hyperlipidemic type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Phytother Res. 2019;33(4):1173–81.

Ho JN, Jang JY, Yoon HG, Kim Y, Kim S, Jun W, et al. Anti-obesity effect of a standardised ethanol extract from Curcuma longa L. fermented with aspergillus oryzae in Ob/Ob mice and primary mouse adipocytes. J Sci Food Agric. 2012;92(9):1833–40.

Ståhlman M, Fagerberg B, Adiels M, Ekroos K, Chapman JM, Kontush A, et al. Dyslipidemia, but not hyperglycemia and insulin resistance, is associated with marked alterations in the HDL lipidome in type 2 diabetic subjects in the DIWA cohort: impact on small HDL particles. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-molecular and cell biology of. Lipids. 2013;1831(11):1609–17.

De Sousa RAL. Brief report of the effects of the aerobic, resistance, and high-intensity interval training in type 2 diabetes mellitus individuals. Int J Diabetes Develop Countries. 2018;38(2):138–45.

Yiu WF, Kwan PL, Wong CY, Kam TS, Chiu SM, Chan SW, et al. Attenuation of fatty liver and prevention of hypercholesterolemia by extract of Curcuma longa through regulating the expression of CYP7A1, LDL-receptor, HO-1, and HMG-CoA reductase. J Food Sci. 2011;76(3):H80–H9.

Shephard RJ, Gannon G, Hay J, Shek P. Adhesion molecule expression in acute and chronic exercise. Crit Rev Immunol. 2000;20(3):245–66.

Hvas A-M, Neergaard-Petersen S. Influence of exercise on platelet function in patients with cardiovascular disease. Seminars in thrombosis and hemostasis: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2018. p. 802–812.

Borges YG, Cipriano LHC, Aires R, Zovico PVC, Campos FV, de Araújo MTM, et al. Oxidative stress and inflammatory profiles in obstructive sleep apnea: are short-term CPAP or aerobic exercise therapies effective? Sleep and Breathing. 2020;24(2):541–9.

Pedersen BK. Anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: role in diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Eur J Clin Investig. 2017;47(8):600–11.

Teixeira-Lemos E, Nunes S, Teixeira F, Reis F. Regular physical exercise training assists in preventing type 2 diabetes development: focus on its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2011;10(1):1–15.

de Lemos ET, Reis F, Baptista S, Pinto R, Sepodes B, Vala H, et al. Exercise training is associated with improved levels of C-reactive protein and adiponectin in ZDF (type 2) diabetic rats. Med Sci Monit 2007;13(8):BR168-BR74.

Oliveira VN, Bessa A, Jorge MLMP, Oliveira RJS, de Mello MT, De Agostini GG, et al. The effect of different training programs on antioxidant status, oxidative stress, and metabolic control in type 2 diabetes. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2012;37(2):334–44.

Devries MC, Hamadeh MJ, Glover AW, Raha S, Samjoo IA, Tarnopolsky MA. Endurance training without weight loss lowers systemic, but not muscle, oxidative stress with no effect on inflammation in lean and obese women. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45(4):503–11.

Fantuzzi G. Adipose tissue, adipokines, and inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115(5):911–9.

Gielen S, Adams V, Möbius-Winkler S, Linke A, Erbs S, Yu J, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of exercise training in the skeletal muscle of patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(5):861–8.

Petersen AMW, Pedersen BK. The anti-inflammatory effect of exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98(4):1154–62.

Leclercq IA, Farrell GC, Sempoux C, dela Peña A, Horsmans Y. Curcumin inhibits NF-κB activation and reduces the severity of experimental steatohepatitis in mice. J Hepatol. 2004;41(6):926–34.

Vizzutti F, Provenzano A, Galastri S, Milani S, Delogu W, Novo E, et al. Curcumin limits the fibrogenic evolution of experimental steatohepatitis. Lab Investig. 2010;90(1):104–15.

Panzhinskiy E, Hua Y, Lapchak PA, Topchiy E, Lehmann TE, Ren J, et al. Novel curcumin derivative CNB-001 mitigates obesity-associated insulin resistance. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2014;349(2):248–57.

Panahi Y, Khalili N, Hosseini MS, Abbasinazari M, Sahebkar A. Lipid-modifying effects of adjunctive therapy with curcuminoids–piperine combination in patients with metabolic syndrome: results of a randomized controlled trial. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2014;22(5):851–7.

Sahebkar A, Serban M-C, Ursoniu S, Banach M. Effect of curcuminoids on oxidative stress: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Funct Foods. 2015;18:898–909.

Sahin K, Pala R, Tuzcu M, Ozdemir O, Orhan C, Sahin N, et al. Curcumin prevents muscle damage by regulating NF-κB and Nrf2 pathways and improves performance: an in vivo model. J Inflamm Res. 2016;9:147.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the subjects for their willing participation in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Rastegar Hoseini designed the study. Mahsa Ahmadi Darmian experimented. Sanam Golshani analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. Ehsan Amiri was involved in the interpretation of data, reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical permission

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Razi University of Kermanshah (IR.RAZI.REC.1400.013) and was registered in the Iranian Clinical Trial Registration Center (code: IRCT20201129049524N1).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Darmian, M.A., Hoseini, R., Amiri, E. et al. Downregulated hs-CRP and MAD, upregulated GSH and TAC, and improved metabolic status following combined exercise and turmeric supplementation: a clinical trial in middle-aged women with hyperlipidemic type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Metab Disord 21, 275–283 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40200-022-00970-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40200-022-00970-z