Abstract

Background

Federal standards authorize the commercialization of generic medicines after bioequivalence versus the brand-name originator has been demonstrated. For drugs with narrow therapeutic indexes, such as warfarin, the accepted difference in bioavailability is ≤ 10%. No systematic pharmacovigilance studies are conducted once generics become available.

Objective

We aimed to assess the impact of the arrival of generic warfarin on hospital visit trends (hospital admissions or emergency room consultations) in warfarin users.

Methods

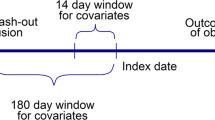

This was an observational interrupted time series analysis (2 January 1996 to 1 January 2016). Using the Québec Integrated Chronic Disease Surveillance System, we included all patients who were aged ≥ 66 years, publicly covered and using brand-name or generic warfarin (N = 280,158). We estimated rates of hospital visits in 6-month periods, 5 years before and up to 15 years after the arrival of generic warfarin. Periods before and after were compared using segmented regression models for all users along with exploratory (generic vs. brand name)/subgroup analyses (cardiovascular comorbidities and socioeconomic status).

Results

Generic warfarin arrived on the market on 2 January 2001. Over the 20-year period of the study, the mean rate of hospital visits was 113 for 100 brand-name or generic users per 6-month period and was similar before and after the arrival of the generics. Up to 15 years after the arrival of the generics, the rates of hospital visits were 10% higher for generic than for brand-name users, which was confirmed by subgroup analyses.

Conclusions

Overall, we observed no impact on hospital visits after the arrival of generic warfarin in all the population treated with any type of warfarin. However, a higher crude rate of hospital visits among generic users than brand-name users remains to be validated using a different methodology and specific outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bristol-Myers Squibb Canada. Monographie de produit: Coumadin (warfarine). 2017. Accessed 16 février 2018 at https://www.bmscanada.ca/static/products/fr/pm_pdf/COUMADIN_FR_PM.pdf.

United States Patent and Trademark Office. General information concerning patents. 2016. Accessed 21 novembre 2016 at https://www.uspto.gov/patents-getting-started/general-information-concerning-patents.

Office de la Propriété Intellectuelle du Canada. Base de données sur les brevets canadiens. 2013. Accessed 03 Avril 2015 at http://brevets-patents.ic.gc.ca/opic-cipo/cpd/fra/aide/contenu/aide_informations_generales.html.

Régie de L’assurance Maladie du Québec. Liste des médicaments. 2017. Accessed 18 décembre 2017 at http://www.ramq.gouv.qc.ca/fr/regie/publications-legales/Pages/liste-medicaments.aspx.

Santé Canada. Ligne directrice - Normes en matière d’études de biodisponibilités comparatives: Formes pharmaceutiques de médicaments à effets systémiques. 2018. Accessed 2 novembre 2018 at https://www.canada.ca/fr/sante-canada/services/medicaments-produits-sante/medicaments/demandes-presentations/lignes-directrices/biodisponibilite-bioequivalence/normes-matiere-etudes-biodisponibilite-comparatives-formes-pharmaceutiques-medicaments-effets-systemiques.html

Rubinstein E. Letter-draft FDA guidance “Considerations in Demonstrating Interchangeability with a Reference Product”: overview and presentation-related concerns. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23:266.

Davit B, et al. International guidelines for bioequivalence of systemically available orally administered generic drug products: a survey of similarities and differences. AAPS J. 2013;15:974–90.

Sameer RG, et al. Hemorrhagic and thrombotic events associated with generic substitution of warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a retrospective analysis. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45:701–12.

Kwong WJ, et al. Resource use and cost implications of switching among warfarin formulations in atrial fibrillation patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46:1609–16.

Kesselheim A, et al. Clinical equivalence of generic and brand-name drugs used in cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:2514–26.

Manzoli L, et al. Generic versus brand-name drugs used in cardiovascular diseases. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31:351–68.

Leclerc J, et al. Impact of the commercialization of three generic angiotensin II receptor blockers on adverse events in Quebec, Canada: a population-based time series analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcome. 2017;10:1–9.

Lopez Bernal J, et al. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:348–55.

Wagner AK, et al. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27:299–309.

Blais C, et al. Quebec integrated chronic disease surveillance system (QICDSS), an innovative approach. Chronic Dis Injury Can. 2014;34:226–35.

Novopharm. Monographie de produit: Novo-warfarin (warfarin). 2005. Accessed 19 février 2018 at https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/drug-products/drug-product-database.html.

Taro Pharmaceuticals Inc. Monographie de produit: Taro-warfarin (warfarin). 2018. Accessed 19 février 2018 at https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/drug-products/drug-product-database.html.

Nu-Pharm Inc. Monographie de produit: Nu-warfarin (warfarin). 2009. Accessed 19 février 2018 at https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/drug-products/drug-product-database.html.

Mylan Pharmaceuticals. Product monograph: Mylan-warfarin (warfarin). 2011. Accessed 19 février 2018 at https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/drug-products/drug-product-database.html.

Sanis Health Inc. Monographie de produit: Warfarin (warfarin). 2012. Accessed 19 février 2018 at https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/drug-products/drug-product-database.html.

Morningstar BA, et al. Variation in pharmacy prescription refill adherence measures by type of oral antihyperglycaemic drug therapy in seniors in Nova Scotia, Canada. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27:213–20.

Wilchesky M, et al. Validation of diagnostic codes within medical services claims. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:131–41.

Pampalon R, et al. A comparison of individual and area-based socio-economic data for monitoring social inequalities in health. Health Rep. 2009;20:85–94.

Leclerc J, et al. Higher rates of adverse events for generic compared to brand-name clopidogrel users: a population-based time series analysis (Submitted).

Gouvernement du Québec. Mesure d’économie concernant les médicaments - Nouvelles règles concernant le recours à la mention ne pas substituer. 2015. Accessed 9 septembre 2016 at www.msss.gouv.qc.ca/documentation/salle-de-presse/ficheCommunique.php?id=878.

Paterson JM, et al. Clinical consequences of generic warfarin substitution: an ecological study. JAMA. 2006;296:1969–72.

Lambert L, et al. Evaluation of care and surveillance of cardiovascular disease: can we trust medico-administrative hospital data? Can J Cardiol. 2012;28:162–8.

Gouvernement du Canada. Loi canadienne sur la santé. 1985. Accessed 31 Mars 2016 at http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/fra/lois/c-6/.

Gagne J, et al. Outcomes associated with generic drugs approved using product-specific determinations of therapeutic equivalence. Drugs. 2017;77:427–33.

Alter D. When do we decide that generic and brand-name drugs are clinically equivalent? Perfecting decisions with imperfect evidence. Circulation. 2017;10.

Strom BL. Study designs avaiable for pharmacoepidemiologic studies. In: Strom BL, Kimmel ST, Hennessy S, editors. Textbook of pharmacoepidemiology, Chap. 2, 2nd edn. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell; 2013. p. 456.

Dal Pan GJ et al. Postmarketing spontaneous pharmacovigilance reporting systems. In: Strom BL, Kimmel SE, Hennessy S, editors. Textbook of pharmacoepidemiology, Chap. 7, 2nd edition. West Sussex: Wiley; 2013. p. 456.

Vittinghoff E. Regression methods in biostatistics: linear, logistic, survival, and repeated measures models. New York: Springer; 2012. p. 340.

Tamblyn R, et al. The use of prescription claims databases in pharmacoepidemiological research: the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the prescription claims database in Quebec. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995;48:999–1009.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the INSPQ, the ministry of health and social services and the Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec (RAMQ) for providing the data used as part of the provincial’s government plan for continuous chronic disease surveillance mandate.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Paul Poirier has received honoraria for continuing medical education/consultants/experts events from Abbott Vascular, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, and Valeant. Jacinthe Leclerc, Claudia Blais, Louis Rochette, Denis Hamel and Line Guénette have no potential conflicts of interest that might be relevant to the contents of this manuscript.

Funding

No external funding was used in the preparation of this manuscript as it was part of the continuous chronic disease surveillance mandate in Québec, Canada. Jacinthe Leclerc was the recipient of two PhD studentships during this project: (1) from the Fondation de l’Institut universitaire de cardiologie et de pneumologie de Québec-Université Laval and (2) from the Société Québécoise d’insuffisance cardiaque, alliance BMS-Pfizer. Line Guénette holds a Junior-1 clinical researcher salary award from the FRQ-S in partnership with the Société québécoise d’hypertension artérielle. Paul Poirier is a senior clinical researcher of the Fonds de recherche du Québec-Santé (FRQ-S).

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leclerc, J., Blais, C., Rochette, L. et al. Trends in Hospital Visits for Generic and Brand-Name Warfarin Users in Québec, Canada: A Population-Based Time Series Analysis. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 19, 287–297 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40256-018-0309-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40256-018-0309-9