Abstract

Background

Alcohol dependence causes considerable harm to patients. Treatment with nalmefene, aiming to reduce consumption rather than maintain complete abstinence, has been licensed based on trials demonstrating a reduction in total alcohol consumption and heavy drinking days. Relating these trial outcomes to harmful events avoided is important to demonstrate the clinical relevance of nalmefene treatment.

Methods

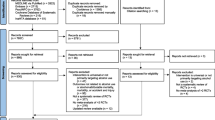

A predictive microsimulation model was developed to compare nalmefene plus brief psychosocial intervention (BRENDA) versus placebo plus BRENDA for the treatment of patients with alcohol dependence and a high or very high drinking risk level based on three pooled clinical trials. The model simulated patterns and level of alcohol consumption, day-by-day, for 12 months, to estimate the occurrence of alcohol-attributable diseases, injuries and deaths; assessing the clinical relevance of reducing alcohol consumption with treatment.

Results

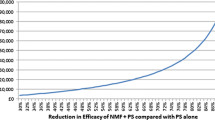

The microsimulation model predicted that, in a cohort of 100,000 patients, 971 (95 % confidence interval [CI] 904–1038) alcohol-attributable diseases and injuries and 133 (95 % CI 117–150) deaths would be avoided with nalmefene versus placebo. This level of benefit has been considered clinically relevant by the European Medicines Agency.

Conclusions

This microsimulation model supports the clinical relevance of the reduction in alcohol consumption, and has estimated the extent of the public health benefit of treatment with nalmefene in patients with alcohol dependence and a high or very high drinking risk level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

BRENDA therapy consists of six components: Biopsychosocial evaluation, Report to the patient on assessment, Empathic understanding of the patient’s situation, Needs collaboratively identified by the patients and treatment provider, Direct advice to the patient on how to meet those needs, and Assess reaction of the patient to advice and adjust as necessary for best care [16].

References

Rehm J, Roerecke M. Reduction of drinking in problem drinkers and all-cause mortality. Alcohol Alcohol. 2013;48(4):509–13.

Thorsen T. Hundrede års alkoholmisbrug: alkoholforbrug og alkoholproblemer i Danmark. Copenhagen: Alkohol- og Narkotikarådet; 1990.

Ledermann S. Alcool, alcoolisme, alcoolisation. Paris: Presses universitaries de France; 1956.

Laramée P, Leonard S, Buchanan-Hughes A, Warnakula S, Daeppen J-B, Rehm J. Risk of all-cause mortality in alcohol-dependent individuals: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. EBioMedicine. 2015;2(10):1394–404.

Rehm J, Zatonksi W, Taylor B, Anderson P. Epidemiology and alcohol policy in Europe. Addiction. 2011;106(Suppl 1):11–9.

Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2224–60.

Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, Thavorncharoensap M, Teerawattananon Y, Patra J. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373(9682):2223–33.

World Health Organization (WHO). Global health risks. Mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009.

World Health Organization (WHO). Global status report on alcohol and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014.

Rehm J, Baliunas D, Borges GL, Graham K, Irving H, Kehoe T, et al. The relation between different dimensions of alcohol consumption and burden of disease: an overview. Addiction. 2010;105(5):817–43.

Rehm J, Room R, Graham K, Monteiro M, Gmel G, Sempos CT. The relationship of average volume of alcohol consumption and patterns of drinking to burden of disease: an overview. Addiction. 2003;98(9):1209–28.

Hemström Ö, Leifman H, Ramstedt M. The ECAS survey on drinking patterns and alcohol-related problems. Alcohol in Postwar Europe: consumption, drinking patterns, consequences and policy responses in 15 European countries. Stockholm: National Institute of Public Health; 2002.

European Medicines Agency (EMA). Guideline on the development of medicinal products for the treatment of alcohol dependence. London: Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use; 2010.

van den Brink W, Aubin HJ, Bladstrom A, Torup L, Gual A, Mann K. Efficacy of as-needed nalmefene in alcohol-dependent patients with at least a high drinking risk level: results from a subgroup analysis of two randomized controlled 6-month studies. Alcohol Alcohol. 2013;48(5):570–8.

van den Brink W, Sorensen P, Torup L, Mann K, Gual A, For the Sense Study Group. Long-term efficacy, tolerability and safety of nalmefene as-needed in patients with alcohol dependence: a 1-year, randomised controlled study. J Psychopharmacol. 2014;28(8):733–44.

Starosta AN, Leeman RF, Volpicelli JR. The BRENDA model: integrating psychosocial treatment and pharmacotherapy for the treatment of alcohol use disorders. J Psychiatr Pract. 2006;12(2):80–9.

Francois C, Laramee P, Rahhali N, Chalem Y, Aballea S, Millier A, et al. A predictive microsimulation model to estimate the clinical relevance of reducing alcohol consumption in alcohol dependence. Eur Addict Res. 2014;20(6):269–84.

The NHS Information Centre. Hospital Episode Statistics for England. Inpatient statistics, 2010–11.

Horton NJ, Kim E, Saitz R. A cautionary note regarding count models of alcohol consumption in randomized controlled trials. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7(1):9.

World Health Organization (WHO). The global burden of disease: 2004 update. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008.

Rehm J, Room R, Taylor B. Method for moderation: measuring lifetime risk of alcohol-attributable mortality as a basis for drinking guidelines. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2008;17(3):141–51.

Roerecke M, Rehm J. Irregular heavy drinking occasions and risk of ischemic heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(6):633–44.

Gerlich MG, Kramer A, Gmel G, Maggiorini M, Luscher TF, Rickli H, et al. Patterns of alcohol consumption and acute myocardial infarction: a case-crossover analysis. Eur Addict Res. 2009;15(3):143–9.

Patra J, Taylor B, Irving H, Roerecke M, Baliunas D, Mohapatra S, et al. Alcohol consumption and the risk of morbidity and mortality for different stroke types–a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):258.

Guiraud V, Amor MB, Mas JL, Touze E. Triggers of ischemic stroke: a systematic review. Stroke. 2010;41(11):2669–77.

Rehm J, Taylor B, Mohapatra S, Irving H, Baliunas D, Patra J, et al. Alcohol as a risk factor for liver cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29(4):437–45.

Irving HM, Samokhvalov AV, Rehm J. Alcohol as a risk factor for pancreatitis. A systematic review and meta-analysis. JOP. 2009;10(4):387–92.

Samokhvalov AV, Irving HM, Rehm J. Alcohol consumption as a risk factor for pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138(12):1789–95.

Rehm J, Scafato E. Indicators of alcohol consumption and attributable harm for monitoring and surveillance in European Union countries. Addiction. 2011;106(Suppl 1):4–10.

Taylor BJ, Shield KD, Rehm JT. Combining best evidence: a novel method to calculate the alcohol-attributable fraction and its variance for injury mortality. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):265.

Scilab Enterprises. Scilab: free and open source software for numerical computation (Version 5.3.3). 2012.

Breslow NE, Clayton DG. Approximate inference in generalized linear mixed models. J Am Stat Assoc. 1993;88(421):9–25.

Dean CB, Nielsen JD. Generalized linear mixed models: a review and some extensions. Lifetime Data Anal. 2007;13(4):497–512.

Akaike H. Information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. Second International Symposium on Information Theory. Budapest: Akademiai Kiado; 1973.

Cavanaugh JE. Lecture II: the Akaike Information Criterion. [unpublished PowerPoint slides]. 171:290 Model Selection. Department of Biostatistics, Department of Statistics and Actuarial Science, The University of Iowa. Lecture given 28th August 2012.

Taylor B, Irving HM, Kanteres F, Room R, Borges G, Cherpitel C, et al. The more you drink, the harder you fall: a systematic review and meta-analysis of how acute alcohol consumption and injury or collision risk increase together. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;110(1–2):108–16.

Roerecke M, Rehm J. The cardioprotective association of average alcohol consumption and ischaemic heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2012;107(7):1246–60.

Taylor B, Rehm J, Room R, Patra J, Bondy S. Determination of lifetime injury mortality risk in Canada in 2002 by drinking amount per occasion and number of occasions. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(10):1119–25 (discussion 26–31).

O’Hagan A, Stevenson M, Madan J. Monte Carlo probabilistic sensitivity analysis for patient level simulation models: efficient estimation of mean and variance using ANOVA. Health Econ. 2007;16(10):1009–23.

EMA. Assessment report—Selincro. 2012. Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/002583/WC500140326.pdf. Accessed 07 Aug 2015.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Nalmefene for reducing alcohol consumption in people with alcohol dependence: appraisal consultation document [TA325]. 2014.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Clinical Guidelines (CG115): alcohol dependence and harmful alcohol use. 2011.

electronic Medicines Compendium (eMC). Summary of Product Characteristics: Selincro 18 mg tablets. Updated 04/06/2015.

Heather N, Adamson SJ, Raistrick D, Slegg GP. Initial preference for drinking goal in the treatment of alcohol problems: I. Baseline differences between abstinence and non-abstinence groups. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;45(2):128–35.

Rehm J, Shield KD, Rehm MX, Gmel G, Frick U. Alcohol consumption, alcohol dependence and attributable burden of disease in Europe: potential gains from effective interventions for alcohol dependence. Toronto: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health; 2012.

Sheffield University. Modelling to assess the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of public health related strategies and interventions to reduce alcohol attributable harm in England using the Sheffield Alcohol Policy Model, version 2.0. 2009.

Brodtkorb TH, Bell M, Irving AH, Laramee P. The cost effectiveness of nalmefene for reduction of alcohol consumption in alcohol-dependent patients with high or very high drinking-risk levels from a UK societal perspective. CNS Drugs. 2016;30(2):163–77.

World Health Organization (WHO). Global status report on alcohol. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004.

Shield K, Kehoe T, Gmel G, Rehm M, Rehm J. Societal burden of alcohol. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2012.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Public Health Guidance (PH24): Alcohol-use disorders—preventing harmful drinking. 2010.

Stevenson M, Pandor A, Stevens JW, Rawdin A, Rice P, Thompson J, et al. Nalmefene for reducing alcohol consumption in people with alcohol dependence: an evidence review group perspective of a NICE single technology appraisal. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33(8):833–47.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Consultation on Batch 30 and Batch 31 draft remits and draft scopes and summary of comments and discussions at scoping workshops. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/media/default/About/what-we-do/NICE-guidance/NICE-technology-appraisals/Block-scoping-reports/Batch-30-and-31-block-scoping-report.pdf. Accessed 16 Dec 2015.

Corrao G. Liver cirrhosis mortality trends in Eastern Europe, 1970–1989. Analyses of age, period and cohort effects and of latency with alcohol consumption. Addict Biol. 1998;3(4):413–22.

Ramstedt M. Per capita alcohol consumption and liver cirrhosis mortality in 14 European countries. Addiction. 2001;96(1s1):19–33.

Rehm J, Scafato E. Indicators of alcohol consumption and attributable harm for monitoring and surveillance in European Union countries. Addiction. 2011;106:4–10.

Laramée P, Brodtkorb TH, Rahhali N, Knight C, Barbosa C, François C, et al. The cost-effectiveness and public health benefit of nalmefene added to psychosocial support for the reduction of alcohol consumption in alcohol-dependent patients with high/very high drinking risk levels: a Markov model. BMJ Open. 2014;4(9):e005376.

World Health Organization (WHO). International guide for monitoring alcohol consumption and related harm. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000.

Office for National Statistics. Population estimates for UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, Mid-2014. 2014.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). CG115 Costing Report: alcohol-use disorders: alcohol dependence. 2011.

Acknowledgments

Editorial and medical writing support was provided by Stephen Montgomery, Sara Steeves and Saoirse Leonard from Costello Medical Consulting Ltd, Cambridge, UK. This support was funded by Lundbeck SAS.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the conception and design of all or some component(s) of the research. Acquisition of data was carried out by PL, AM, NR, OC, SA and JR. Modelling and statistical analysis was performed by PL, AM, NR, OC, SA, and JR. All authors participated at all or some step(s) of the review, analysis and interpretation of the outcomes. PL was responsible for development of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and commented on the draft manuscript, and reviewed its intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. PL will act as the overall guarantor.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

NR and CF are employees of Lundbeck SAS, who funded this work. PL and YC were employees of Lundbeck SAS at the time of the development of this work. AM, OC and SA are employees of Creativ-Ceutical, who were contracted by Lundbeck SAS to undertake some of the work described in this manuscript. JR has received grants, consulting fees/honoraria, travel support and payment for lectures from Lundbeck, outside the work presented in this manuscript. MT declares no conflicts of interest.

This work was funded by Lundbeck SAS. The views presented in this paper are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect those of the study funders. Editorial and medical writing support was provided by Costello Medical Consulting Ltd, and was funded by Lundbeck SAS.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Laramée, P., Millier, A., Rahhali, N. et al. A Trial-Based Predictive Microsimulation Assessing the Public Health Benefits of Nalmefene and Psychosocial Support for the Reduction of Alcohol Consumption in Alcohol Dependence. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 14, 493–505 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-016-0248-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-016-0248-z