Abstract

Background and Objective

Clinical guidelines recommend monotherapy with antidepressants for the treatment of major depression. This study examined prescription patterns with regard to both duration and type of treatment used among patients with newly diagnosed non-psychotic major depression based on a claims database from health insurance societies between 2008 and 2011 in Japan.

Methods

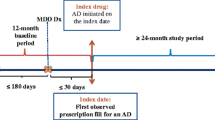

A retrospective cohort (N = 600,000) followed up for 4 years was used to identify patients (age ≥18 years) with newly diagnosed non-psychotic major depression. The prescription patterns and polypharmacy were examined. Four different types of pharmaceutical drugs were defined as possible psychotropic agents for major depression: (1) first- and/or second-generation antidepressants; (2) benzodiazepines; (3) sulpiride; and (4) antipsychotics. The data were analyzed by an intent-to-treat approach at months 0, 1, 3, 6, and 12 from the date of diagnosis.

Results

A total of 7,338 patients (3,684 males and 3,654 females, mean age 36.8 ± 10.9 years) with newly diagnosed non-psychotic major depression were identified. The median duration of treatment was 122 days. The proportion of patients in the cohort prescribed at least one type of defined psychotropic agents was 75.6 % (month 0), 47.3 % (month 1), 36.0 % (month 3), 26.8 % (month 6), and 17.4 % (month 12). The proportion of patients in the cohort prescribed at least one first- and/or second-generation antidepressant was 50.2 % (month 0), 34.9 % (month 1), 27.5 % (month 3), 20.3 % (month 6), and 12.5 % (month 12). The proportion of patients receiving at least one benzodiazepine was 58.0 % (month 0), 36.7 % (month 1), 27.1 % (month 3), 20.0 % (month 6), and 12.0 % (month 12). The proportion of patients receiving an antidepressant as monotherapy was only 12.0 % (month 0), 7.8 % (month 1), 6.5 % (month 3), 4.8 % (month 6), and 2.9 % (month 12), whereas the proportion of patients treated with a benzodiazepine alone was 13.5 % (month 0), 6.9 % (month 1), 4.6 % (month 3), 3.5 % (month 6), and 2.7 % (month 12). Various combinations of polypharmacy were observed. The most common was a combination of at least one antidepressant and benzodiazepine, which was prescribed to 36.7 % (month 0), 25.8 % (month 1), 19.9 % (month 3), 14.9 % (month 6), and 9.2 % (month 12) of the cohort.

Conclusions

Based on analysis of prescription patterns and type of treatment used for treating non-psychotic major depression, a majority of patients were not treated according to the recommended guidelines in Japan. Various patterns of prescription and use of polypharmacy were observed over time. The median duration of treatment was shorter than the recommendation (6 months) in the guidelines.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Tokyo, Japan. Patient survey 2008. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare; 2008.

Furukawa TA, Akechi T, Shimodera S, et al. Strategic use of new generation antidepressants for depression: SUN(^_^)D study protocol. Trials. 2011;11(12):116.

Motohashi N, editor. Pharmacotherapy algorithms for mood disorders. Tokyo: Jihou; 2003.

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Depression: the treatment and management of depression in adults (updated edition). Leicester: British Psychological Society; 2010. NICE Clinical Guidelines, no. 90.

Lam RW, Kennedy SH, Grigoriadis S, The Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT), et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. III. Pharmacotherapy. J Affect Disord. 2009;117(Suppl 1):S26–43.

Texas Department of State Health Services. Texas medication algorithm project procedural manual: major depressive disorder algorithms, USA. 2008 http://www.pbhcare.org/pubdocs/upload/documents/TMAP%20Depression%202010.pdf. Accessed 12 Jan 2013.

Treatment guideline II: major depressive disorder, 2012, ver. 1. Tokyo: The Japanese Society of Mood Disorders (JSMD); 2012.

Sawada N, Uchida H, Suzuki T, et al. Persistence and compliance to antidepressant treatment in patients with depression: a chart review. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;16(9):38.

Uchida N, Chong MY, Tan CH, et al. International study on antidepressant prescription pattern at 20 teaching hospitals and major psychiatric institutions in East Asia: analysis of 1,898 cases from China, Japan, Korea, Singapore and Taiwan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;61(5):522–8.

National Health Insurance (NHI) price dictionary, 2012 April version. Tokyo: Jiho; 2012.

Ueshima K, Higuchi T, Kanba S, et al. Views on drug therapy for depression: proposals based on the field survey [in Japanese]. Jpn Med J. 2005;4262:18–62.

Inagaki A. Prescription patterns of antidepressant. Health and labour sciences research 2002 [in Japanese]. http://www.ncnp.go.jp/tmc/pdf/22_report03.pdf. Accessed 20 Jan 2013.

Ray WA. Evaluating medication effects outside of clinical trials: new-user designs. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(9):915–20.

Japan Medical Data Center Co. Ltd. Tokyo, Japan [in Japanese]. http://www.jmdc.co.jp/en/srv_pharma/jdm.html. Accessed 21 Jan 2013.

Kimura S, Sato T, Ikeda S, et al. Development of a database of health insurance claims: standardization of disease classifications and anonymous record linkage. J Epidemiol. 2010;20(5):413–9.

International Classification of Disease, 10th revision (ICD-10) diagnosis codes, vol. 2. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004.

Master of diseases and injuries names version 3 [in Japanese]. Tokyo: Medical Information System Development Center (MEDIS-DC); 2011.

Davidson JR. Major depressive disorder treatment guidelines in America and Europe. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(Suppl E1):e04.

Furukawa TA, Streiner DL, Young LT. Antidepressant and benzodiazepine for major depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(1):CD001026.

Pfeiffer P, Ganoczy D, Zivin K, et al. Benzodiazepines and adequacy of initial antidepressant treatment for depression. Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(3):360–4.

Lai IC, Wang MT, Wu BJ, et al. The use of benzodiazepine monotherapy for major depression before and after implementation of guidelines for benzodiazepine use. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2011;36(5):577–84.

Lader MH, Petursson H. Benzodiazepine derivatives—side effects and dangers. Biol Psychiatry. 1981;16:1195–201.

Pecknold JC. Discontinuation reaction to alprazolam in panic disorder. J.Psychiatr. Res. 1993;27(Suppl. 1):155–70.

Richels K, Case WG, Dowing RW, et al. Long-term diazepam therapy and clinical outcome. JAMA. 1983;250:767–71.

Maeda H, Egami H, Tomita M, et al. How does sulpiride work and how is it utilized? Jpn J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;10(10):1853–60.

Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, et al. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on alcoholism and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(10):1097–106.

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095–105.

Felker BL, Hedrick SC, Chaney EF, et al. Identifying depressed patients with a high risk of comorbid anxiety in primary care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;5(3):104–10.

Clayton PJ, Grove WM, Coryell W, et al. Follow-up and family study of anxious depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(11):1512–7.

Wu CH, Erickson SR, Piette JD, et al. The association of race, comorbid anxiety, and antidepressant adherence among Medicaid enrollees with major depressive disorder. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2012;8(3):193–205.

Morehouse R, Macqueen G, Kennedy SH. Barriers to achieving treatment goals: a focus on sleep disturbance and sexual dysfunction. J Affect Disord. 2011;132(Suppl 1):S14–20.

Acknowledgment

No sources of funding were used to assist in the conduct of this study or the preparation of the manuscript. TAF has received honoraria for speaking at CME meetings sponsored by Asahi Kasei, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Mochida, MSD, Otsuka, Pfizer Shionogi, and Tanabe-Mitsubishi. He is a diplomate of the Academy of Cognitive Therapy. He has received royalties from Igaku-Shoin, Seiwa-Shoten, and Nihon Bunka Kagaku-sha. He is on the advisory board for Sekisui Chemicals and Takeda Science Foundation. The Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology, the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, and the Japan Foundation for Neuroscience and Mental Health have funded his research projects. SH has received honoraria for a luncheon meeting as a speaker at the Annual Meeting of Japanese Cancer Association by Sanofi K.K. He has received honoraria for speaking at the J-CaPURE joint meeting supported by Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. He has received honoraria for an evening seminar at Annual Meeting of the Japanese Society of Urolithiasis Research sponsored by Astra Zeneca K.K. He has received honoraria for an educational lecture at the Japanese Society of BCG Instillation Therapy sponsored by Japan BCG Laboratory. The Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology, and the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare have funded his research projects. KK has received a grant from Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd, Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co., Ltd, Olympus Corporation, and Taiho Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd. He has received honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo Company, Ltd, Behringer Ingelheim Japan, Inc., Senju Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd, Toray industries Inc., Maruho Co., Ltd, Canon Inc., Olympus Corporation, Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co., Ltd, Kaken Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Novartis K.K., Otsuka Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd, and Eisai Co., Ltd. He has received honoraria for lectures from the Japan Medical Data Center Co., Ltd. YO is an employee at Sanofi.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Onishi, Y., Hinotsu, S., Furukawa, T.A. et al. Psychotropic Prescription Patterns Among Patients Diagnosed With Depressive Disorder Based on Claims Database in Japan. Clin Drug Investig 33, 597–605 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40261-013-0104-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40261-013-0104-y