Abstract

Background

Amisulpride is an antipsychotic used in a wide range of doses. One of the major adverse events of amisulpride is hyperprolactinemia, and the drug might also induce body weight gain.

Objective

The aims of this work were to characterize the pharmacokinetics of amisulpride in order to suggest optimal dosage regimens to achieve the reference range of trough concentrations at steady-state (Cmin,ss) and to describe the relationship between drug pharmacokinetics and prolactin and body weight data.

Methods

The influence of clinical and genetic characteristics on amisulpride pharmacokinetics was quantified using a population approach. The final model was used to simulate Cmin,ss under several dosage regimens, and was combined with a direct Emax model to describe the prolactin data. The effect of model-based average amisulpride concentrations over 24 h (Cav) on weight was estimated using a linear model.

Results

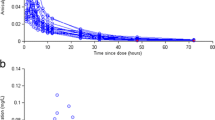

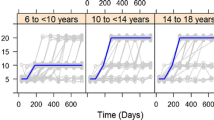

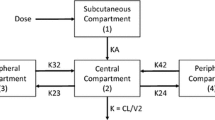

A one-compartment model with first-order absorption and elimination best fitted the 513 concentrations provided by 242 patients. Amisulpride clearance significantly decreased with age and increased with lean body weight (LBW). Cmin,ss was higher than the reference range in 65% of the patients aged 60 years receiving 400 mg twice daily, and in 82% of the patients aged > 75 years with a LBW of 30 kg receiving 200 mg twice daily. The pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model included 101 prolactin measurements from 68 patients. The Emax parameter was 53% lower in males compared with females. Model-predicted prolactin levels were above the normal values for Cmin,ss within the reference range. Weight gain did not depend on Cav.

Conclusions

Amisulpride treatment might be optimized when considering age and body weight. Hyperprolactinemia and weight gain do not depend on amisulpride concentrations. Modification of the amisulpride dosage regimen is not appropriate to reduce prolactin concentrations and alternative treatment should be considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Mauri MC, Paletta S, Di Pace C, Reggiori A, Cirnigliaro G, Valli I, et al. Clinical pharmacokinetics of atypical antipsychotics: an update. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2018;57(12):1493–528.

Muller MJ, Regenbogen B, Hartter S, Eich FX, Hiemke C. Therapeutic drug monitoring for optimizing amisulpride therapy in patients with schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41(8):673–9.

Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, Mavridis D, Orey D, Richter F, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;382:951–62.

Hiemke C, Bergemann N, Clement HW, Conca A, Deckert J, Domschke K, et al. Consensus guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring in neuropsychopharmacology: update 2017. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2018;51(1–02):9–62.

Peuskens J, Pani L, Detraux J, De Hert M. The effects of novel and newly approved antipsychotics on serum prolactin levels: a comprehensive review. CNS Drugs. 2014;28(5):421–53.

Iwata Y, Nakajima S, Caravaggio F, Suzuki T, Uchida H, Plitman E, et al. Threshold of dopamine D2/3 receptor occupancy for hyperprolactinemia in older patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(12):e1557–63.

Besnard I, Auclair V, Callery G, Gabriel-Bordenave C, Roberge C. Antipsychotic-drug-induced hyperprolactinemia: physiopathology, clinical features and guidance [in French]. Encephale. 2014;40(1):86–94.

Juruena MF, de Sena EP, de Oliveira IR. Safety and tolerability of antipsychotics: focus on amisulpride. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2010;2:205–11.

Holt RI, Peveler RC. Antipsychotics and hyperprolactinaemia: mechanisms, consequences and management. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2011;74(2):141–7.

During SW, Nielsen MO, Bak N, Glenthoj BY, Ebdrup BH. Sexual dysfunction and hyperprolactinemia in schizophrenia before and after six weeks of D2/3 receptor blockade: an exploratory study. Psychiatry Res. 2019;274:58–65.

Reeves S, Bertrand J, D’Antonio F, McLachlan E, Nair A, Brownings S, et al. A population approach to characterise amisulpride pharmacokinetics in older people and Alzheimer’s disease. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2016;233(18):3371–81.

Reeves S, Bertrand J, McLachlan E, D’Antonio F, Brownings S, Nair A, et al. A population approach to guide amisulpride dose adjustments in older patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(7):e844–51.

Leucht S, Wagenpfeil S, Hamann J, Kissling W. Amisulpride is an “atypical” antipsychotic associated with low weight gain. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2004;173(1–2):112–5.

Ivanyuk A, Livio F, Biollaz J, Buclin T. Renal drug transporters and drug interactions. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2017;56(8):825–92.

Janmahasatian S, Duffull SB, Ash S, Ward LC, Byrne NM, Green B. Quantification of lean bodyweight. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44(10):1051–65.

Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16(1):31–41.

Pai MP. Estimating the glomerular filtration rate in obese adult patients for drug dosing. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2010;17:e53–62.

Beal S, Sheiner LB, Boeckmann A, Bauer RJ. NONMEM User’s Guides (1989–2009). Ellicott City: Icon Development Solutions; 2009.

Lindbom L, Pihlgren P, Jonsson EN, Jonsson N. PsN-Toolkit—a collection of computer intensive statistical methods for non-linear mixed effect modeling using NONMEM. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2005;79:241–57.

Savic RM, Karlsson MO. Importance of shrinkage in empirical bayes estimates for diagnostics: problems and solutions. AAPS J. 2009;11(3):558–69.

Taylor DM, Barnes TRE, Young AH. The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. 13th ed. New York: Wiley Blackwell; 2018.

Citrome L. Current guidelines and their recommendations for prolactin monitoring in psychosis. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22(2 Suppl):90–7.

Rosenzweig P, Canal M, Patat A, Bergougnan L, Zieleniuk I, Bianchetti G. A review of the pharmacokinetics, tolerability and pharmacodynamics of amisulpride in healthy volunteers. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2002;17:1–13.

Bergemann N, Kopitz J, Kress KR, Frick A. Plasma amisulpride levels in schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004;14(3):245–50.

Dos Santos Pereira JN, Tadjerpisheh S, Abu Abed M, Saadatmand AR, Weksler B, Romero IA, et al. The poorly membrane permeable antipsychotic drugs amisulpride and sulpiride are substrates of the organic cation transporters from the SLC22 family. AAPS J. 2014;16:1247–58.

Solian® comprimés. http://www.swissmedicinfo.ch/. Accessed 14 Jan 2019.

Graff-Guerrero A, Rajji TK, Mulsant BH, Nakajima S, Caravaggio F, Suzuki T, et al. Evaluation of antipsychotic dose reduction in late-life schizophrenia: a prospective dopamine D2/3 receptor occupancy study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(9):927–34.

Lange B, Mueller JK, Leweke FM, Bumb JM. How gender affects the pharmacotherapeutic approach to treating psychosis—a systematic review. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2017;18(4):351–62.

Sparshatt A, Taylor D, Patel MX, Kapur S. Amisulpride – dose, plasma concentration, occupancy and response: implications for therapeutic drug monitoring. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;120(6):416–28.

Lako IM, van den Heuvel ER, Knegtering H, Bruggeman R, Taxis K. Estimating dopamine D(2) receptor occupancy for doses of 8 antipsychotics: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33(5):675–81.

Tsuboi T, Bies RR, Suzuki T, Mamo DC, Pollock BG, Graff-Guerrero A, et al. Hyperprolactinemia and estimated dopamine D2 receptor occupancy in patients with schizophrenia: analysis of the CATIE data. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;45:178–82.

Chen JX, Su YA, Bian QT, Wei LH, Zhang RZ, Liu YH, et al. Adjunctive aripiprazole in the treatment of risperidone-induced hyperprolactinemia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;58:130–40.

Grigg J, Worsley R, Thew C, Gurvich C, Thomas N, Kulkarni J. Antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia: synthesis of world-wide guidelines and integrated recommendations for assessment, management and future research. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2017;234(22):3279–97.

Huang Y, Ma H, Wang Y, Peng M, Zhu G. Topiramate add-on treatment associated with normalization of prolactin levels in a patient with schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:1395–7.

Haddad PM, Wieck A. Antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinaemia: mechanisms, clinical features and management. Drugs. 2004;64(20):2291–314.

Veldhuis JD, Johnson ML. Operating characteristics of the hypothalamo-pituitary–gonadal axis in men: circadian, ultradian, and pulsatile release of prolactin and its temporal coupling with luteinizing hormone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1988;67(1):116–23.

Rosenbloom AL. Hyperprolactinemia with antipsychotic drugs in children and adolescents. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/159402.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank A. C. Aubert, M. Brawand, M. Brocard, C. Brogli, N. Cochard, C. Darbellay, M. Delessert, S. Jaquet, G. Viret and A. Vullioud for sample analyses and data collection; E. Retamales for help with the bibliography; M. Gholamrezaee for his helpful advice on statistical analysis; and G. Sibailly for her instructive and helpful comments on the clinical aspect of this work. The authors are also grateful to the patients who agreed to participate in the study, and to the nursing and medical staff who were involved in the metabolic monitoring program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AG wrote the manuscript and analyzed the data. MG reviewed the manuscript and supervised the data analysis. AD reviewed the manuscript and collected the data. CD reviewed the manuscript and collected the data. CG reviewed the manuscript and collected the data. NL reviewed the manuscript and collected the data. AG reviewed the manuscript and collected the data. PC reviewed the manuscript, collected the data, and obtained funding. CC reviewed the manuscript and supervised the data analysis. CBE reviewed the manuscript, designed the research, and obtained funding.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work has been funded in part by the Swiss National Research Foundation (CE and PC: 320030-120686, 324730-144064, and 320030-173211). The funding sources had no role in the writing of the manuscript or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. CE received honoraria for conferences or teaching continuing medical education courses from Astra Zeneca, Forum für Medizinische Fortbildung, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Mepha, Otsuka, Sandoz, Servier, Vifor-Pharma and Zeller over the past 3 years, and for writing a review article for the journal ‘Dialogues in Clinical Neurosciences’ (Servier).

Conflict of interest

Anaïs Glatard, Monia Guidi, Aurélie Delacrétaz, Céline Dubath, Claire Grosu, Nermine Laaboub, Armin von Gunten, Philippe Conus, Chantal Csajka and Chin B. Eap declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest that might be relevant to the contents of this manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Glatard, A., Guidi, M., Delacrétaz, A. et al. Amisulpride: Real-World Evidence of Dose Adaptation and Effect on Prolactin Concentrations and Body Weight Gain by Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Analyses. Clin Pharmacokinet 59, 371–382 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-019-00821-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-019-00821-w