Abstract

Up to 50 % of heart failure patients suffer from lower urinary tract symptoms. Urinary incontinence has been associated with worse functional status in patients with heart failure, occurring three times more frequently in patients with New York Heart Association Class III and IV symptoms compared with those with milder disease. The association between heart failure and urinary symptoms may be directly attributable to worsening heart failure pathophysiology; however, medications used to treat heart failure may also indirectly provoke or exacerbate urinary symptoms. This type of drug–disease interaction, in which the treatment for heart failure precipitates incontinence, and removal of medications to relieve incontinence worsens heart failure, can be termed therapeutic competition. The mechanisms by which heart failure medication such as diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and β-blockers aggravate lower urinary tract symptoms are discussed. Initiation of a prescribing cascade, whereby antimuscarinic agents or β3-agonists are added to treat symptoms of urinary urgency and incontinence, is best avoided. Recommendations and practical tips are provided that outline more judicious management of heart failure patients with lower urinary tract symptoms. Compelling strategies to improve urinary outcomes include titrating diuretics, switching ACE inhibitors, treating lower urinary tract infections, appropriate fluid management, daily weighing, and uptake of pelvic floor muscle exercises.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

While medications are essential for palliating symptoms and improving survival, prescription of additional medications for one condition may commonly precipitate or worsen other co-morbidities. Therapeutic competition is a type of bidirectional drug–disease interaction that occurs when treatment for the first condition adversely impacts the second, and subsequent treatment of the second condition exacerbates the first [1]. An important example of therapeutic competition is between heart failure treatment and urinary incontinence, a common geriatric syndrome. Urinary incontinence reduces dignity, autonomy and mood in later life and should be prevented at all costs [2]. This article reviews the mechanisms and possible solutions for managing therapeutic competition between heart failure and lower urinary tract symptoms in older adults.

Heart failure affects 1–3 % of the general population [3, 4]. The prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms is much higher, reported to occur in over 50 % of men and women [5]. Urinary frequency, urinary urgency, nocturia and urinary incontinence are among the most common lower urinary tract symptoms [5, 6]. Urinary incontinence can be subclassified into stress, urgency, and mixed or functional incontinence. Involuntary urine leakage that occurs with coughing, laughing or sneezing is called stress incontinence and is caused by intravesicular pressures that exceed urethral closing pressures. Urgency incontinence is associated with a sudden, compelling urge to void, and often coexists with other symptoms of overactive bladder such as frequency, urgency and nocturia. Functional incontinence has typically been described in frail older adults with mobility or cognitive impairment, and refers to the inability to reach the toilet in time to void [7].

Studies indicate that 35–50 % of heart failure patients suffer from urinary incontinence [8–10]. Urinary incontinence is associated with reduced functional capacity in older adults with heart failure [11]. Although urinary symptoms may antedate the diagnosis of heart failure, urinary urgency with or without incontinence is found to be 2.9 times (95 % CI 1.3–6.3) more prevalent in patients with New York Heart Association Class III or Class IV heart failure compared with Class I or Class II. This suggests that worsening heart failure either provokes or exacerbates urinary symptoms [12]. A direct association between heart failure pathophysiology and bladder dysfunction may explain this relationship; or perhaps other co-morbidities such as diabetes mellitus or renal failure play a role [13–15]. Alternatively, medications such as diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and β-blockers, which are frequently prescribed for patients with heart failure, may indirectly be at cause.

Mr. S. is an 84-year-old man recently admitted to hospital with decompensated heart failure. He had an ST-elevation myocardial infarction 10 years ago and again last year. Prior to his admission he was active and well. Upon discharge his medications included Monopril® 10 mg orally daily, furosemide 40 mg orally twice daily, aldactone 25 mg orally twice daily, bisoprolol 5 mg orally daily, atorvastatin 20 mg orally daily, metformin 850 mg orally twice daily, acetylsalicylic acid (ASA, aspirin) 80 mg orally daily, pantoprazole 40 mg orally daily, and oxazepam 15 mg orally every night. Three months post-discharge he has become increasingly depressed, and is no longer enjoying activities such as golfing with his friends. He experiences urinary urgency eight to ten times per day, four times nightly, and regularly leaks urine on the way to the toilet. He is reluctant to go out for fear of leakage and odor. His self-esteem is low, he does not want to wear protective undergarments and he is rapidly losing the will to live.

2 Mechanisms Underlying the Risk of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in Heart Failure Patients

Direct precipitation of lower urinary tract symptoms during heart failure can be due to compensatory secretion of natriuretic peptides [16]. Natriuretic peptides play an important role in the body’s regulation of intravascular volume by promoting excretion of sodium and elimination of bodily fluid. A number of natriuretic peptides have been identified: atrial natriuretic peptide, urodilantin, brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), C-type natriuretic peptide and Dendroaspis natriuretic peptide [16]. BNP has been widely studied in relation to cardiac load, with levels typically rising and falling in association with the severity of heart failure symptoms. Released from ventricular cardiomyocytes in response to an increase in ventricular wall tension, BNP has been shown to fluctuate in parallel with hemodynamic measures such as left ventricular end diastolic pressure. Binding of BNP to the natriuretic peptide A receptor stimulates a signaling cascade that results in natriuresis and inhibition of renin and aldosterone. Both European and North American heart failure guidelines recognize value in measuring BNP levels as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker of heart failure in patients with dyspnea [17, 18]. High BNP levels have been independently associated with the presence and severity of nocturnal voiding, as well as nocturnal polyuria in elderly patients [19]. Redistribution and elimination of fluid from peripheral or pulmonary edema further contribute to urinary frequency and excessive diuresis, especially at night when peripheral edema is resorbed in the supine position.

Chronic heart failure patients experience fatigue and may also become deconditioned due to dyspnea-related activity restriction. In patients with New York Heart Association class III–IV symptoms, reduced functional capacity and decreased mobility are important risk factors for urinary incontinence, as both impede the ability to reach the toilet in a timely manner during episodes of urinary urgency [11]. Predisposing risk factors for lower urinary tract symptoms, such as pelvic floor muscle weakness, obesity, or consumption of caffeinated beverages, may synergistically augment the risk of incontinence in the presence of heart failure pathology. Exacerbation of pre-existing symptoms of incontinence can also occur.

Indirect effects of both acute and chronic heart failure on the lower urinary tract may be mediated by prescription of medications for both tertiary prevention and symptomatic relief. Drug therapy in heart failure is essential for slowing disease progression and for improvement of symptoms and survival [20]. However, as a part of their modes of action or as side effects, many of these medications can iatrogenically contribute to urinary frequency, urgency, nocturia or incontinence [8, 21–23].

3 Heart Failure Medications that Precipitate or Worsen Urinary Incontinence

Although diuretics are typically used to relieve congestion, and ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) improve survival, these classes of drugs have been suggested to accelerate and worsen urinary symptoms in the presence of heart failure. β-blockers are also frequently prescribed for heart failure patients and can potentially have an impact on the lower urinary tract. Because heart failure, urinary problems and use of these medications are common in old age, this is above all a geriatric complication.

3.1 Diuretics

Diuretics are part of the first-line treatment for symptomatic relief of heart failure. These drugs increase sodium urinary excretion and decrease physical signs of fluid retention [24]. Clinical trials have shown that the use of diuretics leads to a reduction in venous pressure, edema and body weight [25], with the consequence of providing symptomatic relief and improvement of quality of life for patients with heart failure and preserved systolic function [26]. These symptomatic benefits occur more rapidly with diuretics than for other heart failure drugs. The long-term effects include improvement in cardiac function and exercise tolerance, with positive effects on morbidity and mortality [24].

Nonetheless, the desired actions of diuretics in heart failure—increased urine sodium excretion and volume of urine—can also cause urinary frequency, urgency and incontinence [27]. There are, however, differences between loop diuretics and non-loop diuretics, where loop diuretics have been more often associated with urinary tract symptoms. Use of loop diuretics has been related to increased urinary frequency and urgency [28], whereas non-loop diuretics have not.

Studies on incontinence are conflicting. Cross-sectional analyses have suggested that diuretics may be implicated in causing incontinence [29, 30], whereas longitudinal studies have not confirmed this finding [31, 32].

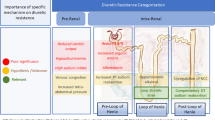

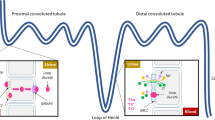

The later stages of heart failure are characterized by fluid overload and a chronic state of overhydration. At this stage, even high doses of loop diuretics might prove ineffective, a phenomenon known as diuretic resistance [33, 34]. An important mechanism behind diuretic resistance is functional adaptation of the distal tubule after chronic exposure to loop diuretics. One way to overcome the problem is to add diuretics acting on different sites of the nephron [34]. Typically, a thiazide-type diuretic, hydralazine, or other potassium-sparing or mineralocorticoid diuretics are combined with loop diuretic therapy to attain diuretic synergy. This is common clinical practice, although there is a lack of high-level evidence for use of this combination. While the combination therapy can prove effective for resistant patients, it can also cause hypokalemia and worsening renal function [33]. Additionally, the synergistic effects of combination therapy may cause heavy diuresis, potentially aggravating urinary frequency and urgency in late-stage heart failure patients. However, this has, to our knowledge, not yet been investigated.

3.2 Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitors

ACE inhibitors are standard therapy in heart failure patients with symptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction. They have been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality in clinical trials; however, there is less evidence for treatment with ACE inhibitors in all patients with heart failure and in those with preserved ejection fraction [35]. Although ACE inhibitors are generally well tolerated, they are associated with a persistent cough probably caused by increased levels of bradykinin and tachykinin. The ACE inhibitor-induced cough is characterized by being dry, non-productive and worse at night [36], and occurs in 5–35 % of patients taking ACE inhibitors [37]. This cough can produce or exacerbate stress incontinence by increasing urethral pressure. A number of case reports have described cough-induced stress incontinence upon initiation of an ACE inhibitor, which remits upon discontinuation [38, 39]. One case series reported a 10 % incidence of severe drug-induced stress incontinence in diabetic post-menopausal women initiating ACE inhibitors [40].

3.3 β-Blockers

β-Blockers have been extensively studied in the treatment of heart failure, and are standard treatment for improvement of clinical outcomes of heart failure patients [41]. There is a chronic activation of the sympathetic nervous system in heart failure in an attempt to restore cardiac output. This is a compensatory mechanism that provides inotropic support to the failing heart by increasing stroke volume and peripheral vasoconstriction. However, these measures eventually accelerate disease progression and negatively affect survival [42]. β-Blockers affect heart failure by inhibiting sympathetic nervous system activation. This effect has been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality in several clinical trials [20]. In the context of incontinence, emerging evidence suggests that β-blockers may increase bladder contractility and provoke symptoms of urinary urgency [30, 43]. The effects of β-blockers on the risk of incontinence are, however, inconsistent [44, 45] and require further investigation.

4 Overactive Bladder Medications that Precipitate or Worsen Heart Failure

Avoidance of prescribing cascades in the elderly is a key tenet of pharmacologic management in this population. Increased urinary frequency and urgency due to diuretic dose escalation during acute heart failure episodes may motivate patients to consult for incident symptoms of overactive bladder. The overactive bladder syndrome comprises symptoms of urinary urgency, with or without urinary frequency and nocturia, in the presence or absence of urgency urinary incontinence [6]. Consultation for overactive bladder may lead to prescription of one of two oral pharmaceutical classes of medication for the treatment of overactive bladder symptoms. Both antimuscarinic agents and β3-adrenergic agonists have proven efficacy for reducing symptoms of urinary frequency, urgency and incontinence [46, 47]. If a proper medication history is not ascertained, and neither the patient nor the consultant makes the link between heart failure medications and urinary symptoms, a prescribing cascade for the treatment of overactive bladder may ensue.

4.1 Antimuscarinic Agents

Antimuscarinic drugs are the mainstay of treatment for patients with symptoms of overactive bladder, including urgency incontinence. Blockade of M2 and M3 receptors in the bladder detrusor muscle reduces urinary urgency, frequency and urgency incontinence. However, blockade of muscarinic cholinergic receptors (primarily M2 subtype) on sinoatrial nodal cells can also potentially increase heart rate, which is best avoided in patients with heart failure [48]. Several antimuscarinic agents are approved for the treatment of overactive bladder syndrome, all with different relative affinities for the M2 subtype [48]. QT interval prolongation and induction of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (torsade de pointes) are other theoretical concerns with the use of antimuscarinic agents in heart failure patients [48]; however, few studies have specifically investigated whether antimuscarinic agents exert these effects in the real-life setting. Based on available information, any effects that exist appear to be modest and their clinical relevance unknown. Data suggest that the prevalence of cardiovascular co-morbidities is significantly higher in patients with than without overactive bladder, and that cardiovascular co-morbidities are found to be more prevalent in treated versus untreated patients (58.8 vs. 53.7 %; p < 0.001). The association between antimuscarinic agents and cardiovascular adverse events therefore warrants further investigation [49, 50].

4.2 β3-Adrenoceptor Agonists

The β3-adrenoceptor subtype is dominant in the human detrusor muscle, and activation of the β3-adrenoceptor mediates relaxation of the detrusor during the storage phase of the micturition cycle, improving bladder storage capacity without impeding bladder voiding [47]. Mirabegron is a selective β3-adrenoceptor agonist approved for the treatment of overactive bladder. β3-adrenoceptors are thought to account for more than 95 % of all β-adrenergic messenger RNA in the human bladder, and are highly and preferentially expressed on urinary bladder tissues, including the urothelium, interstitial cells and detrusor smooth muscle [47]. Concern about cross-reactivity with β1- and β2-adrenoceptor subtypes found in the vasculature and cardiac muscle, as well as direct stimulation of β3-adrenoceptors in the heart, have raised concern about the cardiac safety of mirabegron in heart failure patients [51].

A meta-analysis of three randomized clinical trials with a pool of over 2,760 patients looked at treatment-emergent adverse effects due to mirabegron [47]. Adverse effects included hypertension (odds ratio [OR] 0.91, 95 % CI 0.68–1.21) and cardiac arrhythmias (OR 1.67, 95 % CI 0.95–2.92, p = 0.07). These results suggest no obvious effect of β3-agonists on cardiac function in participants in these trials. However, interpretation must be made with caution as the study population was not representative of elderly patients with multiple morbidities and chronic heart failure, although many were on β-blockers for the treatment of hypertension. Further research is warranted on the specific effects of β3-agonists in heart failure patients, as well as the combined use of β-blockers and β-agonists in this population.

At Mr. S’s 3-month follow-up visit his depression is apparent. He is disheveled and talks about constantly needing to run to the toilet. Screening questions reveal that he experiences urge incontinence which is affecting his sense of dignity. Dyspnea on exertion and orthopnea are absent. Pedal edema is minimal. His skin turgor is low and he complains of dry mouth. Urinalysis is negative. His diabetes is well-controlled but his renal function has worsened. He has started drinking two bottles of beer in the evening. Mr. S. does not know why he is taking oxazepam; he says it was prescribed upon discharge from hospital. He wants to know if there are medications to take to control his urine leakage.

5 Management of Therapeutic Competition in Patients with Heart Failure and Urinary Symptoms

Recommendations and practical tips for the management of heart failure patients with lower urinary tract symptoms entail a variety of pharmacological modifications and non-pharmacological interventions. Figure 1 illustrates different therapeutic approaches to patients with stress incontinence, symptoms of urinary frequency and urgency—including urgency incontinence—and nocturia. A sudden change in urinary symptoms may signal newly decompensated heart failure or the presence of a urinary tract infection. These possibilities should be ruled out and addressed prior to proceeding with other management strategies.

5.1 Dose Reduction of Diuretics

Consider reassessing the need and reducing the dose of diuretics if the patient is otherwise stable. Although complete discontinuation of diuretics can lead to decompensation and relapse [52], many patients are discharged from hospital after an acute episode with high-dose oral diuretics, equivalent to the intravenous doses that were required to relieve symptoms upon admission. When acute congestion is cleared, the lowest dose should be used that is compatible with stable signs and symptoms.

5.2 Substitution of ACE Inhibitors with Angiotensin Receptor Blockers

ARBs do not inhibit degradation of bradykinin, thought to be responsible for the ACE inhibitor-induced cough. ARBs and ACE inhibitors are equal in terms of reduction of mortality and morbidity in heart failure patients, but discontinuation due to adverse effects is lower with ARBs [53]. Therefore, switching to an ARB may be an alternative to avoid the side effect of coughing and consequent stress incontinence associated with ACE inhibitor use [40, 53].

5.3 Rule-Out Reversible Causes of Hospital-Related Morbidity

-

(a)

Catheter-induced urinary tract infection Patients in cardiogenic shock or those admitted with acute heart failure who have difficulty voiding often have a urinary catheter inserted to monitor urinary output. In-dwelling catheters provide a nidus for bacterial entry into the normally sterile lower urinary tract, and increase the risk of lower urinary tract infection. Exacerbation of lower urinary tract symptoms including urinary frequency, urgency, nocturia and incontinence post-hospitalization for acute heart failure may indicate the presence of a new urinary tract infection. Attribution of symptoms to an increased dose of diuretics may confound early diagnosis and treatment, especially as dysuria and hematuria are less commonly seen as presenting symptoms and signs of urinary tract infection in the elderly [54]. Recent guidance from the American Board of Internal Medicine for adult hospital medicine recommends that urinary catheters not be placed, or left in place, to monitor urinary output in non-critically ill patients, and that weights should be used instead to track diuresis [55].

-

(b)

Sedative-hypnotic prescriptions Admission to the intensive care or coronary care unit for treatment of acute heart failure elicits anxiety among patients as they grapple with the impending possibility of mortality. Anxiety, combined with the need to reduce adrenergic stimulation and sleeplessness due to the beeps and disruptions inherent to any high-intensity monitoring unit, often leads to prescription of a sedative hypnotic [56]. Evidence suggests that many of these sedative-hypnotic prescriptions persist upon discharge, with hospitalization conferring a 2.7-fold greater risk of incident use than outpatient visits [57]. Medications that bind to GABAA receptors in the central nervous system can potentially affect the lower urinary tract system either directly, by causing relaxation of striated pelvic floor muscles and/or by interfering with afferent sensory messages from the bladder, or even indirectly through an effect on mobility and toileting ability [21, 58]. For this reason, as well as many others, sedative-hypnotic medications are not recommended in elderly heart failure patients and should be tapered and discontinued. Cognitive behavioral therapy is a safer and equally efficacious alternative to treat insomnia in the ambulatory care setting [59].

5.4 Fluid Management

Fluid restriction represents a key management strategy in patients with chronic heart failure. An individualized fluid management program is recommended for each patient according to the severity of heart failure, renal function and other dietary behaviors. Clinically, 1.5–2 litres per day is recommended for most patients and an intake greater than 2 litres per day is generally discouraged. Patient education with or without provision of self-management strategies for fluid management, sodium restriction, daily weighing and physical conditioning may attenuate urinary problems in heart failure patients, although formal trials are required to test the efficacy of this approach [60, 61]. Patients with recurrent fluid retention who are able to follow instructions can be taught to adjust their diuretic dose based on symptoms of dyspnea on exertion and orthopnea and changes in daily body weight. Use of compression stockings during the day by stable chronic heart failure patients may help prevent distal leg edema, nocturnal fluid redistribution, and nocturnal urinary frequency and urgency [62]. The benefit of compression stockings in patients with decompensated heart failure remains unclear, as the use of compression stockings has been reported to increase right atrial and pulmonary pressures [63].

5.5 Dietary Modification

Caffeinated beverages, such as tea, coffee and colas, may increase urinary urgency and enhance diuresis via the stimulatory effect of caffeine on the bladder detrusor muscle [64, 65]. Even though randomized trials of caffeine reduction in heart failure patients are lacking, epidemiologic data suggest that caffeine intake equivalent to 2 cups (234 mg) or greater than 3 cups (392 mg) of coffee per day is significantly associated with having moderate to severe urinary incontinence in men (1.72, 95 % 1.18–2.49; and 2.08, 95 % 1.15–3.77, respectively), even when adjusting for underlying prostate conditions [66]. Studies of women also reveal that there may be a physiologic link between high caffeine intake, diuresis, and prevalent and incident urgency incontinence [67, 68]. Moderate sodium restriction may also be effective in reducing hospital readmission rates for chronic heart failure patients [69]. Alcohol consumption has been shown to increase the risk of mortality in chronic heart failure patients, although the physiologic mechanism is unclear [70]. Attention to dietary factors should therefore be recommended as part of any conservative management strategy.

5.6 Pelvic Floor Muscle Exercises

Systematic reviews on the effect of pelvic floor muscle training on stress urinary incontinence/mixed urinary incontinence have found that intensive, supervised training can produce clinically important effects on the reduction of urine leakage [71]. Pelvic floor muscle exercises, as part of any conservative management strategy for urgency incontinence, yield equivalent or superior efficacy to pharmacological management, with an uncommon risk of adverse events [72]. Supervision by a trained physiotherapist may augment the effectiveness of pelvic floor muscle training if a patient has difficulty identifying their pelvic floor muscles and/or performing the exercises correctly [73].

5.7 Prescription of Medication for Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms

Although prescription of medication is effective for treating lower urinary tract symptoms, adherence to antimuscarinic agents is poor because of adverse effects such as dry mouth and constipation [74, 75], and the use of β3-agonists has not yet been well-studied in heart failure patients, many of whom are already taking β-blockers. Dry mouth resulting from the use of antimuscarinic agents can paradoxically lead to increased fluid consumption and worsening of heart failure symptoms. Removal of heart failure medications contributing to lower urinary tract symptoms is the preferred management approach, rather than initiating a prescribing cascade and unavoidable therapeutic competition. Conservative management strategies for the treatment of urinary symptoms, such as avoidance of caffeinated beverages and regular performance of pelvic floor muscle exercises should be prioritized as first-line treatment.

Upon hearing that his diuretics and sleeping pill may be contributing to his urinary symptoms, Mr. S. elects a trial of dose reduction and conservative management. He slowly tapers off the benzodiazepine, experiencing withdrawal symptoms that he controls with sleep hygiene techniques and persistence. A routine of daily weighing, fluid restriction and monitoring of dyspnea symptoms allows him to completely taper off aldactone. He cuts out his morning coffee and bedtime alcohol. He wears compression stockings and every morning practices pelvic floor muscle exercises. Under close surveillance from the cardiac team, he is able to reduce his dose of furosemide to only 20 mg daily. He only wakes up twice nightly to urinate and is able to make it to the toilet on time. Three months later he no longer leaks, is no longer depressed and has resumed playing golf with his friends.

6 Conclusion

Up to 50 % of heart failure patients suffer from lower urinary tract symptoms. Urinary frequency, urgency and incontinence are extremely bothersome, while nocturnal symptoms may disrupt sleep and quality of life. Healthcare practitioners should be aware that medications used to treat heart failure may indirectly provoke or exacerbate urinary symptoms, and that tapering diuretics and switching ACE inhibitors for ARBs are reasonable management approaches. Therapeutic competition may occur as the dose of diuretic is reduced, or new medication is added to treat urinary symptoms. Judicious use of medication, combined with patient collaboration for heart failure and lower urinary symptom self-management are likely the best therapeutic approaches for improving outcomes for these challenging co-morbid conditions.

References

Mallet L, Spinewine A, Huang A. The challenge of managing drug interactions in elderly people. Lancet. 2007;370:185–91.

Xu D, Kane RL. Effect of urinary incontinence on older nursing home residents’ self-reported quality of life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(9):1473–81

Roger VL. Epidemiology of heart failure. Circ Res. 2013;113:646–59.

Seferovic PM, Stoerk S, Filippatos G, Mareev V, Kavoliuniene A, Ristic AD, et al. Organization of heart failure management in European Society of Cardiology member countries: survey of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology in collaboration with the Heart Failure National Societies/Working Groups. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:947–59.

Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Thompson CL, Milsom I, Irwin D, Kopp ZS, et al. The prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in the USA, the UK and Sweden: results from the Epidemiology of LUTS (EpiLUTS) study. BJU Int. 2009;104:352–60.

Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, Griffiths D, Rosier P, Ulmsten U, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:167–78.

DuBeau CE, Kuchel GA, Johnson T 2nd, Palmer MH, Wagg A. Incontinence in the frail elderly: report from the 4th International Consultation on Incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29:165–78.

Hwang R, Chuan F, Peters R, Kuys S. Frequency of urinary incontinence in people with chronic heart failure. Heart Lung. 2013;42:26–31.

Lindeman K, Li Y, Palmer MH. Help-seeking for incontinence by individuals with heart failure. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1994–5.

Lee PG, Cigolle C, Blaum C. The co-occurrence of chronic diseases and geriatric syndromes: the health and retirement study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:511–6.

Madigan EA, Gordon N, Fortinsky RH, Koroukian SM, Pina I, Riggs JS. Predictors of functional capacity changes in a US population of Medicare home health care (HHC) patients with heart failure (HF). Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;54:e300–6.

Palmer MH, Hardin SR, Behrend C, Collins SK, Madigan CK, Carlson JR. Urinary incontinence and overactive bladder in patients with heart failure. J Urol. 2009;182:196–202.

Balta S, Kurt O, Cakar M, Demirkol S, Unlu M, Kucuk U. Urinary incontinence in people with chronic heart failure. Heart Lung. 2013;42:154.

Holzmann MJ, Gardell C, Jeppsson A, Sartipy U. Renal dysfunction and long-term risk of heart failure after coronary artery bypass grafting. Am Heart J. 2013;166:142–9.

Balta S, Demirkol S, Karaman M. Renal dysfunction may predict new onset heart failure. Am Heart J. 2013;166:e5.

Kim HN, Januzzi JL Jr. Biomarkers in the management of heart failure. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2010;12:519–31.

McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Bohm M, Dickstein K, et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14:803–69.

McKelvie RS, Moe GW, Ezekowitz JA, Heckman GA, Costigan J, Ducharme A, et al. The 2012 Canadian Cardiovascular Society heart failure management guidelines update: focus on acute and chronic heart failure. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:168–81.

Yoshimura K, Nakayama T, Sekine A, Matsuda F, Kosugi S, Yamada R, et al. B-Type natriuretic peptide as an independent correlate of nocturnal voiding in Japanese women. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:1266–71.

Adorisio R, De Luca L, Rossi J, Gheorghiade M. Pharmacological treatment of chronic heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2006;11:109–23.

Kashyap M, Tu LM, Tannenbaum C. Prevalence of commonly prescribed medications potentially contributing to urinary symptoms in a cohort of older patients seeking care for incontinence. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:57.

Tsakiris P, Oelke M, Michel MC. Drug-induced urinary incontinence. Drugs Aging. 2008;25:541–9.

Hall SA, Chiu GR, Kaufman DW, Wittert GA, Link CL, McKinlay JB. Commonly used antihypertensives and lower urinary tract symptoms: results from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. BJU Int. 2012;109:1676–84.

Faris RF, Flather M, Purcell H, Poole-Wilson PA, Coats AJ. Diuretics for heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(2):CD003838.

Patterson JH, Adams KF Jr, Applefeld MM, Corder CN, Masse BR. Oral torsemide in patients with chronic congestive heart failure: effects on body weight, edema, and electrolyte excretion. Torsemide Investigators Group. Pharmacotherapy. 1994;14:514–21.

Yip GW, Wang M, Wang T, Chan S, Fung JW, Yeung L, et al. The Hong Kong diastolic heart failure study: a randomised controlled trial of diuretics, irbesartan and ramipril on quality of life, exercise capacity, left ventricular global and regional function in heart failure with a normal ejection fraction. Heart. 2008;94:573–80.

Ekundayo OJ. The association between overactive bladder and diuretic use in the elderly. Curr Urol Rep. 2009;10:434–40.

Ekundayo OJ, Markland A, Lefante C, Sui X, Goode PS, Allman RM, et al. Association of diuretic use and overactive bladder syndrome in older adults: a propensity score analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;49:64–8.

Finkelstein MM. Medical conditions, medications, and urinary incontinence: analysis of a population-based survey. Can Fam Physician: Medecin de famille canadien. 2002;48:96–101.

Ruby CM, Hanlon JT, Fillenbaum GG, Pieper CF, Branch LG, Bump RC. Medication use and control of urination among community-dwelling older adults. J Aging Health. 2005;17:661–74.

Ruby CM, Hanlon JT, Boudreau RM, Newman AB, Simonsick EM, Shorr RI, et al. The effect of medication use on urinary incontinence in community-dwelling elderly women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1715–20.

Diokno AC, Brown MB, Herzog AR. Relationship between use of diuretics and continence status in the elderly. Urology. 1991;38:39–42.

Jentzer JC, DeWald TA, Hernandez AF. Combination of loop diuretics with thiazide-type diuretics in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1527–34.

Dormans TP, Gerlag PG, Russel FG, Smits P. Combination diuretic therapy in severe congestive heart failure. Drugs. 1998;55:165–72.

Kazi D, Deswal A. Role and optimal dosing of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in heart failure. Cardiol Clin. 2008;26:1–14, v.

Poole MD, Postma DS. Characterization of cough associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;105:714–6.

Dicpinigaitis PV. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced cough: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129:169S–73S.

Menefee SA, Chesson R, Wall LL. Stress urinary incontinence due to prescription medications: alpha-blockers and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:853–4.

Casanova JE. Incontinence after use of enalapril. J Urol. 1990;143:1237–8.

Lee YJ, Chiang YF, Tsai JC. Severe nonproductive cough and cough-induced stress urinary incontinence in diabetic postmenopausal women treated with ACE inhibitor. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:427–8.

Foody JM, Farrell MH, Krumholz HM. beta-Blocker therapy in heart failure: scientific review. JAMA. 2002;287:883–9.

Triposkiadis F, Karayannis G, Giamouzis G, Skoularigis J, Louridas G, Butler J. The sympathetic nervous system in heart failure physiology, pathophysiology, and clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1747–62.

Lewandowski J, Sinski M, Symonides B, Korecki J, Rogowski K, Judycki J, et al. Beneficial influence of carvedilol on urologic indices in patients with hypertension and benign prostatic hyperplasia: results of a randomized, crossover study. Urology. 2013;82:660–6.

Meigs JB, Barry MJ, Giovannucci E, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Kawachi I. Incidence rates and risk factors for acute urinary retention: the health professionals followup study. J Urol. 1999;162:376–82.

Peron EP, Zheng Y, Perera S, Newman AB, Resnick NM, Shorr RI, et al. Antihypertensive drug class use and differential risk of urinary incontinence in community-dwelling older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67:1373–8.

Buser N, Ivic S, Kessler TM, Kessels AG, Bachmann LM. Efficacy and adverse events of antimuscarinics for treating overactive bladder: network meta-analyses. Eur Urol. 2012;62:1040–60.

Cui Y, Zong H, Yang C, Yan H, Zhang Y. The efficacy and safety of mirabegron in treating OAB: a systematic review and meta-analysis of phase III trials. Int Urol Nephrol. Epub 30 Jul 2013.

Andersson KE, Campeau L, Olshansky B. Cardiac effects of muscarinic receptor antagonists used for voiding dysfunction. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;72:186–96.

Andersson KE, Sarawate C, Kahler KH, Stanley EL, Kulkarni AS. Cardiovascular morbidity, heart rates and use of antimuscarinics in patients with overactive bladder. BJU Int. 2010;106:268–74.

Asche CV, Kim J, Kulkarni AS, Chakravarti P, Andersson KE. Presence of central nervous system, cardiovascular and overall co-morbidity burden in patients with overactive bladder disorder in a real-world setting. BJU Int. 2012;109:572–80.

Andersson KE, Martin N, Nitti V. Selective beta-adrenoceptor agonists for the treatment of overactive bladder. J Urol. 2013;190(4):1173–80.

Graves T, Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Landsman PB, Samsa GP, Pieper CF, et al. Adverse events after discontinuing medications in elderly outpatients. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:2205–10.

Heran BS, Musini VM, Bassett K, Taylor RS, Wright JM. Angiotensin receptor blockers for heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(4):CD003040.

Gavazzi G, Delerce E, Cambau E, Francois P, Corroyer B, de Wazieres B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for urinary tract infection in hospitalized elderly patients over 75 years of age: a multicenter cross-sectional study. Med Mal Infect. 2013;43:189–94.

Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, Goldstein J, O’Callaghan J, Auron M, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486–92.

Johnell K, Fastbom J. The use of benzodiazepines and related drugs amongst older people in Sweden: associated factors and concomitant use of other psychotropics. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:731–8.

Halme AS, Beland SG, Preville M, Tannenbaum C. Uncovering the source of new benzodiazepine prescriptions in community-dwelling older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28:248–55.

Landi F, Cesari M, Russo A, Onder G, Sgadari A, Bernabei R. Benzodiazepines and the risk of urinary incontinence in frail older persons living in the community. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;72:729–34.

Andrews LK, Coviello J, Hurley E, Rose L, Redeker NS. “I’d eat a bucket of nails if you told me it would help me sleep:” perceptions of insomnia and its treatment in patients with stable heart failure. Heart Lung. 2013;42:339–45.

Wright SP, Walsh H, Ingley KM, Muncaster SA, Gamble GD, Pearl A, et al. Uptake of self-management strategies in a heart failure management programme. Eur J Heart Fail. 2003;5:371–80.

Holroyd-Leduc JM, Straus S, Thorpe K, Davis DA, Schmaltz H, Tannenbaum C. Translation of evidence into a self-management tool for use by women with urinary incontinence. Age Ageing. 2011;40:227–33.

Partsch H. Compression therapy: clinical and experimental evidence. Ann Vasc Dis. 2012;5:416–22.

Dereppe H, Hoylaerts M, Renard M, Leduc O, Bernard R, Leduc A. Hemodynamic impact of pressotherapy [in French]. J Mal Vasc. 1990;15:267–9.

Lohsiriwat S, Hirunsai M, Chaiyaprasithi B. Effect of caffeine on bladder function in patients with overactive bladder symptoms. Urol Ann. 2011;3:14–8.

Arya LA, Myers DL, Jackson ND. Dietary caffeine intake and the risk for detrusor instability: a case-control study. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:85–9.

Davis NJ, Vaughan CP, Johnson TM 2nd, Goode PS, Burgio KL, Redden DT, et al. Caffeine intake and its association with urinary incontinence in United States men: results from National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys 2005–2006 and 2007–2008. J Urol. 2013;189:2170–4.

Gleason JL, Richter HE, Redden DT, Goode PS, Burgio KL, Markland AD. Caffeine and urinary incontinence in US women. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:295–302.

Jura YH, Townsend MK, Curhan GC, Resnick NM, Grodstein F. Caffeine intake, and the risk of stress, urgency and mixed urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2011;185:1775–80.

Paterna S, Fasullo S, Parrinello G, Cannizzaro S, Basile I, Vitrano G, et al. Short-term effects of hypertonic saline solution in acute heart failure and long-term effects of a moderate sodium restriction in patients with compensated heart failure with New York Heart Association class III (Class C) (SMAC-HF Study). Am J Med Sci. 2011;342:27–37.

Gargiulo G, Testa G, Cacciatore F, Mazzella F, Galizia G, Della-Morte D, et al. Moderate alcohol consumption predicts long-term mortality in elderly subjects with chronic heart failure. J Nutr Health Aging. 2013;17:480–5.

Hay-Smith EJ, Herderschee R, Dumoulin C, Herbison GP. Comparisons of approaches to pelvic floor muscle training for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(12):CD009508.

Shamliyan T, Wyman J, Kane RL. Nonsurgical treatments for urinary incontinence in adult women: diagnosis and comparative effectiveness. Rockville, MD; 2012.

Herderschee R, Hay-Smith EC, Herbison GP, Roovers JP, Heineman MJ. Feedback or biofeedback to augment pelvic floor muscle training for urinary incontinence in women: shortened version of a Cochrane systematic review. Neurourol Urodyn. 2013;32:325–9.

Johnell K, Fastbom J, Rosen M, Leimanis A. Inappropriate drug use in the elderly: a nationwide register-based study. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:1243–8.

Wagg A, Compion G, Fahey A, Siddiqui E. Persistence with prescribed antimuscarinic therapy for overactive bladder: a UK experience. BJU Int. 2012;110:1767–74.

Acknowledgments

C. Tannenbaum is funded by the Michel Saucier Endowed Chair in Geriatric Pharmacology, Health and Aging from the Faculty of Pharmacy at the Université de Montréal and a senior career award from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec-Santé. C. Tannenbaum declares having served as an occasional invited Advisory Board member or received honoraria for continuing medical education lectures on the evaluation and management of geriatric urinary incontinence from Pfizer, Astellas, Ferring, Watson, and Allergan Pharmaceuticals. These activities have in no way influenced the writing of this manuscript. K. Johnell is supported financially by a grant from the Swedish Research Council.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Tannenbaum, C., Johnell, K. Managing Therapeutic Competition in Patients with Heart Failure, Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms and Incontinence. Drugs Aging 31, 93–101 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-013-0145-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-013-0145-1