Abstract

Background

The use of drugs with anticholinergic properties (AC drugs) has been associated with decreased functioning and impaired cognition in older adults. Studies assessing the association between AC-drug use and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) show conflicting results.

Objective

The aim was to evaluate the association between AC-drug use and HRQoL in community-dwelling older adults.

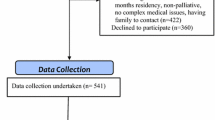

Methods

The NuAge cohort study enrolled 1793 men and women aged 68–82 years. The participants were free of disabilities in activities of daily living, not cognitively impaired at recruitment and followed annually for 3 years (December 2003–May 2005). AC-drug exposure was assessed using the Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale (ACBS). HRQoL was assessed using the physical (PCS) and mental (MCS) component summaries of the 36-item Short Form Survey (SF-36) questionnaire. The association between AC drug and HRQoL was determined by a mixed model analysis using four annual time points.

Results

At recruitment the mean age was 74.4 ± 4.2 years, 52% were female and 33% of participants were prescribed at least one AC drug. The mean PCS and MCS (/100) scores were 49.0 ± 8.2 and 54.9 ± 8.1, respectively. In the mixed model analysis, an increase of 1 on the ACBS was associated with a decrease of −0.50 (95% CI −0.68 to −0.31) in the PCS and an increase of 0.19 (95% CI 0.01–0.37) in the MCS.

Conclusions

In a cohort of generally healthy community-dwelling older adults, AC-drug exposure was associated with a statistically significant decrease in the PCS and increase in the MCS throughout the entire follow-up period. However, the effects on the PCS and MCS were small and likely not clinically relevant.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Seniors and the health care system: what is the impact of multiple chronic conditions? Canadian Institute for Health Information; January 2011. https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/air-chronic_disease_aib_en.pdf. Accessed 15 Feb 2017.

Gandhi TK, Weingart SN, Borus J, et al. Adverse drug events in ambulatory care. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(16):1556–64.

Bressler R, Bahl JJ. Principles of drug therapy for the elderly patient. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(12):1564–77.

Merle L, Laroche ML, Dantoine T, et al. Predicting and preventing adverse drug reactions in the very old. Drugs Aging. 2005;22(5):375–92.

Brown JD, Hutchison LC, Li C, et al. Predictive validity of the Beers and Screening Tool of Older Persons’ Potentially Inappropriate Prescriptions (STOPP) criteria to detect adverse drug events, hospitalizations, and emergency department visits in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(1):22–30.

Henschel F, Redaelli M, Siegel M, et al. Correlation of incident potentially inappropriate medication prescriptions and hospitalization: an analysis based on the PRISCUS list. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2015;2(3):249–59.

Lu WH, Wen YW, Chen LK, et al. Effect of polypharmacy, potentially inappropriate medications and anticholinergic burden on clinical outcomes: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ. 2015;187(4):E130–7.

van der Stelt CA, Windsant-van Vermeulen, den Tweel AM, Egberts AC, et al. The association between potentially inappropriate prescribing and medication-related hospital admissions in older patients: a nested case control study. Drug Saf. 2016;39(1):79–87.

Cahir C, Moriarty F, Teljeur C, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing and vulnerability and hospitalization in older community-dwelling patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(12):1546–54.

American Geriatrics Society. Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227–46.

O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, et al. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44(2):213–8.

Duran CE, Azermai M, Vander Stichele RH. Systematic review of anticholinergic risk scales in older adults. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(7):1485–96.

Hilmer SN, Mager DE, Simonsick EM, et al. A drug burden index to define the functional burden of medications in older people. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(8):781–7.

Reppas-Rindlisbacher CE, Fischer HD, Fung K, et al. Anticholinergic drug burden in persons with dementia taking a cholinesterase inhibitor: the effect of multiple physicians. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(3):492–500.

Sura SD, Carnahan RM, Chen H, et al. Prevalence and determinants of anticholinergic medication use in elderly dementia patients. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(10):837–44.

Mayer T, Haefeli WE, Seidling HM. Different methods, different results—how do available methods link a patient’s anticholinergic load with adverse outcomes? Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;71(11):1299–314.

Nishtala PS, Salahudeen MS, Hilmer SN. Anticholinergics: theoretical and clinical overview. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15(6):753–68.

Ruxton K, Woodman RJ, Mangoni AA. Drugs with anticholinergic effects and cognitive impairment, falls and all-cause mortality in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80(2):209–20.

Fox C, Smith T, Maidment I, et al. Effect of medications with anti-cholinergic properties on cognitive function, delirium, physical function and mortality: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2014;43(5):604–15.

Dominick KL, Ahern FM, Gold CH, et al. Relationship of health-related quality of life to health care utilization and mortality among older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2002;14(6):499–508.

Agar M, Currow D, Plummer J, et al. Changes in anticholinergic load from regular prescribed medications in palliative care as death approaches. Palliat Med. 2009;23(3):257–65.

Bosboom PR, Alfonso H, Almeida OP, et al. Use of potentially harmful medications and health-related quality of life among people with dementia living in residential aged care facilities. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2012;2(1):361–71.

Mate KE, Kerr KP, Pond D, et al. Impact of multiple low-level anticholinergic medications on anticholinergic load of community-dwelling elderly with and without dementia. Drugs Aging. 2015;32(2):159–67.

Ness J, Hoth A, Barnett MJ, et al. Anticholinergic medications in community-dwelling older veterans: prevalence of anticholinergic symptoms, symptom burden, and adverse drug events. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006;4(1):42–51.

Sura SD, Carnahan RM, Chen H, et al. Anticholinergic drugs and health-related quality of life in older adults with dementia. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2015;55(3):282–7.

Sakakibara M, Igarashi A, Takase Y, et al. Effects of prescription drug reduction on quality of life in community-dwelling patients with dementia. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;18(5):705–12.

Gaudreau P, Morais JA, Shatenstein B, et al. Nutrition as a determinant of successful aging: description of the Quebec longitudinal study Nuage and results from cross-sectional pilot studies. Rejuvenation Res. 2007;10(3):377–86.

McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31(3):247–63.

Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–83.

Health Canada Drug Product Database. https://health-products.canada.ca/dpd-bdpp/index-eng.jsp. Accessed 15 Feb 2017.

Boustani M, Campbell N, Munger S, et al. Impact of anticholinergics on the aging brain: a review and practical application. Aging Health. 2008;4(3):311–20.

Carnahan RM, Lund BC, Perry PJ, et al. The Anticholinergic Drug Scale as a measure of drug-related anticholinergic burden: associations with serum anticholinergic activity. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;46(12):1481–6.

Rudolph JL, Salow MJ, Angelini MC, et al. The anticholinergic risk scale and anticholinergic adverse effects in older persons. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(5):508–13.

Salahudeen MS, Duffull SB, Nishtala PS. Anticholinergic burden quantified by anticholinergic risk scales and adverse outcomes in older people: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:31.

Naples JG, Marcum ZA, Perera S, et al. Concordance between anticholinergic burden scales. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(10):2120–4.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–57.

Sourial N, Bergman H, Karunananthan S, et al. Contribution of frailty markers in explaining differences among individuals in five samples of older persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(11):1197–204.

Fillenbaum GG, Smyer MA. The development, validity, and reliability of the OARS multidimensional functional assessment questionnaire. J Gerontol. 1981;36(4):428–34.

McCulloch CE, Searle SR. Generalized, linear, and mixed models. New York: Wiley; 2001. p. 156–86.

Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Automat Contr. 1974;19(6):716–23.

Lu K, Mehrotra DV. Specification of covariance structure in longitudinal data analysis for randomized clinical trials. Stat Med. 2010;29(4):474–88.

Verbeke G, Molenberghs G. Linear mixed models in practice: a SAS-oriented approach, vol. 126. New York: Springer; 1997.

Verbeke G, Molenberghs G. Linear mixed models for longitudinal data. New York: Springer; 1997.

Xanthakis V, Sullivan LM, Vasan RS. Multilevel modeling versus cross-sectional analysis for assessing the longitudinal tracking of cardiovascular risk factors over time. Stat Med. 2013;32(28):5028–38.

Greenland S. Modeling and variable selection in epidemiologic analysis. Am J Publ Health. 1989;79(3):340–9.

Wyrwich KW, Tierney WM, Babu AN, et al. A comparison of clinically important differences in health-related quality of life for patients with chronic lung disease, asthma, or heart disease. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(2):577–91.

Angst F, Aeschlimann A, Stucki G. Smallest detectable and minimal clinically important differences of rehabilitation intervention with their implications for required sample sizes using WOMAC and SF-36 quality of life measurement instruments in patients with osteoarthritis of the lower extremities. Arthr Rheum. 2001;45(4):384–91.

Gray SL, Anderson ML, Dublin S, et al. Cumulative use of strong anticholinergics and incident dementia: a prospective cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(3):401–7.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Samuel Laroche for his help in linking the anticholinergic drug scores with the Health Canada database.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BC, MB, and HP designed the study; BC, MS, and OG analyzed the data; BC, MB, MS, CS, GPL, OG, and HP interpreted the data; BC drafted the manuscript; MB, MS, CS, GPL, OG, JAM, PG and HP critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work was supported by the Quebec Network for Research on Aging. The NuAge study was funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) (MOP-62842) and the Quebec Network for Research on Aging, a network financed by the Fonds de Recherche du Québec–Santé. The funding organizations had no involvement in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing of the manuscript and submission for publication.

Conflict of interest

Benoit Cossette, Maimouna Bagna, Modou Sene, Caroline Sirois, Gabrielle P. Lefebvre, Olivier Germain, José A. Morais, Pierrette Gaudreau and Hélène Payette declare they have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Centre de santé et de services sociaux—Institut universitaire de gériatrie de Sherbrooke ethics committee. Consent was obtained from all research participants at the outset of the NuAge study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cossette, B., Bagna, M., Sene, M. et al. Association Between Anticholinergic Drug Use and Health-Related Quality of Life in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Drugs Aging 34, 785–792 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-017-0486-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-017-0486-2