Abstract

Objective

Our objective was to develop a value set based on Irish utility values for the EuroQol 5-Dimension, 5-Level instrument (EQ-5D-5L).

Methods

The research design and data collection followed a protocol developed by the EuroQol Group. The EuroQol Valuation Technology (EQ-VT) software was administered using computer-assisted personal interviews to a representative sample of adults resident in Ireland between 2015 and 2016. Utility values were elicited using two stated-preference techniques: time trade-off (TTO) and discrete-choice experiment (DCE). Each respondent completed a valuation exercise in which the EQ-VT system randomly selected one block of ten TTO questions from ten blocks relating to a possible 86 health states. One block of seven DCE pairs from 28 blocks of a possible 196 pairs of health states were randomly selected to accompany this. The relationship between utility values and health states was analysed using a hybrid regression model that combined data from the TTO and DCE techniques and expressed these as a function of the health state presented to the individual. This model estimated coefficients for 20 dummy variables that characterised each health state in the EQ-5D-5L framework, with the lowest level of severity providing the reference category in each domain. The relationship between weighted and unweighted TTO and DCE analyses of main effects was analysed separately.

Results

Comparison of weighted and unweighted models revealed no substantive differences in results with respect to either DCE or TTO models. The unweighted hybrid model produced estimated effects, the ordering of which was intuitively consistent within each domain: lower levels of health were associated with lower utility values. Differences were evident between domains with respect to valuations; the disutility associated with conditions related to anxiety/depression and pain/discomfort was higher than for other domains. The decrement in utility associated with movement from the highest to the lowest level of health was 0.344 for mobility, 0.287 for self-care, 0.187 for usual activities, 0.510 for pain/discomfort and 0.646 for anxiety/depression.

Discussion

The results present the first value set based on the EQ-5D-5L framework for a representative sample of residents in Ireland. The set reveals a higher decrement in utility associated with anxiety/depression than with other domains of health. Caution is warranted in comparisons with other value sets. That said, those in England, the Netherlands, Uruguay and China reveal that, whereas Irish values are broadly consistent with respect to mobility, self-care and usual activities, residents of Ireland attach a higher decrement to pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression than do other populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

This paper reports a EuroQol 5-Dimension, 5-Level instrument (EQ-5D-5L) value set for Ireland based on the utility values of residents in 2015–2016. |

These results are useful to those evaluating new healthcare technologies in Ireland and can inform the measurement of patient-reported outcomes more generally. |

1 Introduction

Cost-effectiveness analysis (including cost-utility analysis [CUA]) involves the comparative analysis of alternative uses of healthcare resources in terms of both their cost and their consequences. Interest in this analysis has grown as healthcare budgets have come under increasing pressure and the importance of ensuring and demonstrating value for money in healthcare resources has risen. Because CUA permits very different uses of resources to be compared in terms of value for money, it is recommended as an evaluation technique in guidance offered in many jurisdictions, including Ireland [1] and the UK [2]. Indeed, quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) now inform the allocation of significant amounts of healthcare resource in several countries [3, 4].

The generation of QALYs requires (1) an instrument that measures patients’ health states and (2) a means of assigning weights to those states in a manner that reflects utility values. The EuroQol 5-Dimension instrument (EQ-5D) is the preferred generic measure in the UK [2] and is widely used in other countries. It measures health-related quality of life on five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. In the five-level version of the instrument (EQ-5D-5L), 3125 (55) unique health states can be described, with each dimension categorized on five levels of severity: no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems and extreme problems/unable to [5]. The EQ-5D-5L instrument has been shown to have superior discriminatory power and reduced ceiling effects relative to the three-level version (EQ-5D-3L) [6,7,8,9,10]. Moreover, unlike the EQ-5D-3L instrument, an internationally agreed protocol exists for the generation of utility weights for the EQ-5D-5L [11]. Together with the quality-control procedure developed alongside the valuation protocol [11], and the support provided for data collection by the EuroQol Research Foundation in the conduct of national five-level studies, greater supports now exist to assure the consistency and robustness of EQ-5D-5L value sets relative to three-level versions. These developments have seen the emergence of EQ-5D-5L national value sets in England [12], Canada [13], Korea [14], Indonesia [15], the Netherlands [16], Uruguay [17], Spain [18], Hong-Kong [19], China [20] and Germany [21]. Despite the reticence of the UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) to support the adoption of the five-level version of the instrument while further research is undertaken [22], these instruments have permitted the comparative analysis of national value sets and the generation of cross-walk algorithms for some countries [23].

In Ireland, the importance of health technology assessment has been embraced for some time. National bodies such as the National Centre for Pharmacoeconomics and the Health Information and Quality Authority are involved in economic evaluations, and the latter publishes guidance on the conduct of evaluations in Ireland [1]. Despite this, at the time of writing, no national value set for the generation of utility weights has been published in Ireland. In this paper, we present the methods and results for an Irish EQ-5D-5L value set.

2 Methods

2.1 Design

The research design and data collection followed version 2 of the EQ-5D-5L valuation protocol developed by the EuroQol Group [11, 24] and deployed the EuroQol Valuation Technology (EQ-VT), developed specifically for valuing EQ-5D-5L health states administered using computer-assisted personal interviews. This version of the protocol has been deployed previously in Indonesia [15] and Germany [21]. Utility values were elicited using two stated-preference techniques—composite time trade-off (cTTO) and discrete-choice experiment (DCE)—each providing distinct but complementary preference data. Each respondent completed a valuation exercise in which the EQ-VT system randomly selected one block of ten cTTO tasks from ten blocks relating to a possible 86 health states and one block of seven DCE pairs from 28 blocks of a possible 196 pairs of health states. Values with respect to cTTO tasks were elicited using an iterative procedure. The cTTO approach combined conventional TTO for health states considered better than dead and lead-time TTO for health states that were considered worse than dead by the participant [25]. The cTTO has been used in a number of recently published valuation studies [15, 21] and shown to have face validity [25]. Following the conduct of the cTTO tasks, a ‘feedback module’ was conducted in which the participant was shown the ranking of the ten health states based on his/her cTTO values and given the opportunity to point out any or all responses where they were not satisfied with its relative ranking [26]. This was in turn followed by three debriefing questions regarding how difficult the participant found the cTTO section. A free-text box allowed the participant to make any further comments. Sociodemographic data, including the respondent’s age, sex, education, income and marital status, were collected alongside utility data.

2.2 Sample

Consistent with Oppe and van Hout [27], a representative sample of at least 1000 respondent utility values were required for analysis. A representative sample of Irish residents was drawn using a two-stage stratified clustering process as detailed by Haase and Pratschke [28]. In the first stage, a sample of 54 small areas stratified by income and urban/rural classifications were drawn at random from across the country. In the second stage, within each small area, a sample of approximately 20 houses were selected at random. Random selection was achieved by using a random starting point and inviting a resident from every third house to participate in the survey. To achieve this, each house was visited up to three times throughout the day and early evening in an effort to contact the householder. Where no response was elicited from the selected house, it was replaced from among those in the immediate vicinity, generally based on immediate physical proximity. Within each house, any adult capable of giving informed consent could volunteer to complete the survey, one volunteer per household being chosen at random.

Interviews were conducted by one of a seven-person team of trained surveyors. The interviewer team comprised three males and four females. Each surveyor was trained prior to deployment; training included the conduct of test interviews to ensure the surveyor was competent using the survey instrument. The quality-control process developed by the EuroQol Group was strictly followed, including a commitment to remove batches of observations collected by interviewers who were not compliant with data quality requirements and retrain those interviewers. The survey team met at the end of each week to share their experiences and ensure any issues encountered were dealt with consistently. Ethical approval for the study was granted by NUI Galway Ethics Committee (application number 15/JAN/04).

2.3 Analyses

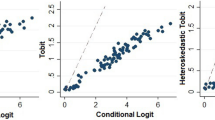

Analyses proceeded in stages. First, we estimated our response rate and compared this across areas with different deprivation and urban/rural statuses. Second, descriptive statistics were calculated that compared the recruited sample with that of the population based on estimates from the Central Statistics Office for Ireland (CSO). In principle, it is possible to address under/over-representation of particular groups by re-weighting a sample. To optimise use of available utility data, both TTO and DCE, a hybrid regression model [29] was estimated where an adjustment was made to account for the censored nature of the data (TTO data were censored at − 1). In essence, the hybrid model [29] maximizes a likelihood function that is the product of the likelihood of combinations of continuous response data from the TTO and DCE responses. Instances where the respondent expressed uncertainty as to the valuation they had given in the feedback module (which occurred in 2% of values) were removed in a manner consistent with that adopted in the German [21] and Indonesian [15] value sets. Similarly, in the interests of improved fit, we used the hetcont() option of the hyreg command as suggested by Ramos-Goñi et al. [29] to correct for heteroscedasticity. The estimated model comprised four dummy variables for each level of health in respect of each domain, (20 dummy variables in all), with the lowest level (no problems) providing the reference category.

Consistent with Solon et al. [30], weighted and unweighted results were estimated and compared to ascertain whether results were materially affected by weighting. As software did not support the direct estimation of weighted results in the hybrid model, weighted (by age and sex) and unweighted versions of the TTO and DCE models were separately estimated and compared (see the Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM]). In further confirmatory analyses (results available in the ESM), a ‘boosted’ sample was generated in which respondents from under-represented age and sex groups were selected with replacement at random and used to augment the existing sample. The numbers were drawn to ensure the sample more closely reflected the CSO estimates in terms of age and sex composition. A main effects hybrid model was estimated on this boosted sample. Finally, a sample in which those from over-represented age and sex groups were again de-selected at random until a sample composition better reflecting that of the CSO estimates was generated (results are available in the ESM). A comparison of the performance of TTO and hybrid models based on their relative likelihoods is not meaningful [31] because the likelihood of the hybrid always exceeds that of the TTO; therefore, this avenue of investigation was not pursued. Fuller details of the methods are provided in the ESM.

3 Results

3.1 Sample Characteristics

In total, 1160 surveys were completed between March 2015 and September 2016, with the survey effort expended equally over the 2 years but confined to the months March to the end of October in both years. As shown in Fig. 1, the randomly selected areas where surveys were undertaken were distributed geographically throughout the country. Purposive sampling to augment the number of younger individuals and males in the sample was undertaken in 2016. This followed a comparison of the recruited sample with that of the CSO population estimates for age and sex nationally. Of the 1160 completed surveys, 102 were purposive. These individuals were identified initially through personal contacts, including work associates with subsequent snowball sampling. Excluding the purposive sample and houses where the householder could not be contacted despite call backs, the response rate to the survey was 47% (which compares with 48% in England [12], one of the few countries to have reported such a statistic). The response rate when households that could not be contacted were included in the denominator was 19% (no comparable data on this were available). An analysis of the relationship between response rates and the level of deprivation in the area studied revealed no significant differences across deprivation levels (results available in the ESM). Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the sample alongside those from the CSO where available. Including the purposive sample, the sample broadly reflects the Irish population, albeit with some over-representation of those aged > 45 years and of males. Those with tertiary-level education were over-represented, and those with only primary-level education were under-represented, compared with the population at large. Our sample also has a slightly larger representation of those with private health insurance and of married individuals, although, with the latter, this may reflect differences in the definitions used or the readiness to report cohabiting in official surveys where entitlement to benefits might be affected.

3.2 Values

Figure 2 shows the percentages of cTTO inconsistencies by type before and after the feedback module. The figures help demonstrate the face validity of the data; only a small percentage of logically inconsistent values were returned and that reduced further after the feedback module was administered. No interviewer required retraining in light of quality assessment of their interviews, nor were any interviewer’s data removed from the sample because of concerns about data quality.

Percentage of responses with inconsistencies. The proportion of respondents whose time trade-off data contain at least one inconsistency of any kind; the proportion of respondents with inconsistencies involving the mildest health states (e.g. valued 21111 lower than another state that dominated 21111); and the proportion of respondents with inconsistencies involving the worst health state (i.e. valued 55555 higher than any other state). These proportions are shown both before and after respondents were given the opportunity to flag data for removal using the feedback module

Table 2 presents the results of the main effects hybrid model. These represent our estimated five-level value set for Ireland. The table also includes a worked example describing the valuation of a health state. A health state that involves slight problems with mobility (2), moderate problems with self-care (3), slight problems with usual activities (2), severe pain/discomfort (4) and moderate anxiety/depression (3) involves the deduction of 0.063, 0.088, 0.049, 0.373 and 0.202 from 1 (perfect health). In separate analyses of TTO and DCE data, the constant was not significant, and data were therefore merged without the constant. As can be seen from the model and reflected in the example, anxiety/depression is the most heavily weighted health domain in Ireland. As can also be seen from Table 2, utility values are non-linear with respect to severity in all domains. For example, the decrement in health associated with a change in mobility, self-care, usual activities from level 3 to 4 is much greater than that from level 1 to 2 or from 2 to 3. (In Table 7 in the ESM, decrements in utility relative to the next level of severity are reported for each domain.) Approximately 36% of our 3125 estimated values were negative, compared with 35% in the Indonesian study [15] that used the same version of the protocol and hybrid modelling approach as deployed here (data for the German study were not reported).

Figure 2 shows that the survey yielded high-quality data with face validity and few inconsistencies (where logically dominant health states were associated with a lower utility than dominated health states) involving mild or severe states. Following training, no surveyor’s data were removed from the sample because of quality concerns. (Fuller details of survey quality are provided in the ESM. Respondents were less likely to express uncertainty regarding values involving ‘worse than death’ states—4% of ‘better than death’ compared with 2% of ‘worse than death’ states being highlighted in the feedback module). While our sample under-represented younger men, it was broadly representative of the population with respect to many other characteristics, including marital status, education, numbers of people living with dependents aged < 18 years and health insurance status. Confirmatory analyses (available in the ESM) revealed no statistically or non-statistically significant differences in results between weighted and unweighted analyses. The sample and the results derived from it can be taken as reflective of the population from which they were drawn. Our data were gathered over the course of 2 years and across seasons, which—while not an issue currently covered by the EuroQol protocol—is also potentially important in terms of quality. Utility value data collected over an extended time period make it less susceptible to effects that might only exist at certain times of the year (e.g. seasonal affective disorder [32]) or the economic cycle [33]. This potentially adds further validity to the data.

4 Discussion

The value set reported was consistent with intuition, that is, greater severity was associated with lower utility values. While the differences between levels of severity are not always statistically significant, the non-linear relationship between utility values and health states across each domain may simply reflect that individuals do not always perceive differences between levels of specific domains the same or perhaps even as material. Clear differences between domains in terms of their impact on utility are evident in our results. As noted, anxiety/depression had a much greater impact on utility than did other domains. Care is warranted in drawing comparisons with other value sets, as many of these were undertaken using an earlier version of the protocol. Comparing Irish values with those in England [12], Canada [13], Korea [14], the Netherlands [16], Uruguay [17], China [20] and Germany [21], broadly similar weights are evident in respect of the most severe levels of self-care, usual activities and mobility, though marked differences between each of these and Indonesia are evident [15]. By contrast, with respect to anxiety/depression, it is clear that Ireland attaches a greater importance to anxiety/depression than do these other countries. For the lowest level of health in this domain, for example, while the decrement is approximately 0.29 in England, 0.18 in Uruguay, 0.23 in China and 0.42 in the Netherlands, it is 0.65 in Ireland. The reason for this is unclear, and—as noted—some care is warranted with the comparison.

The assignment of greater disutility to decrements related to anxiety/depression than to other domains of health is of more than academic importance. Given the role of QALYs in the allocation of healthcare resources and of utility weights in the measurement of QALYs, underestimation of the importance attached to anxiety/depression could result in mental health failing to be accorded the appropriate priority in resource allocation decisions in Ireland.

More broadly, the reported value set has obvious value, not just for evaluation exercises but also for monitoring health. At the time of writing, no national value set exists in Ireland. Notwithstanding NICE hesitating to recommend use of the EQ-5D-5L value set for England, it does support use of the EQ-5D-5L, and the superior discriminatory power and reduced ceiling effects of the EQ-5D-5L as noted have already been demonstrated [6,7,8,9,10]. While research and debate around the merits of EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-5L weights for the UK continues, the development of an EQ-5D-5L value set for Ireland marks an important development where the issues of transitioning from an Irish three-level version are less evident [34].

Our study has a number of limitations. While we collected 1160 usable responses, which, relative to the size of the Irish population, represents a larger sample than in many valuation studies, it would have been preferable to sample still more small areas to provide a greater geographic spread of data. Similarly, while the slight under-representation of younger males in our sample had no substantive effect on estimates, it would have been preferable for our sample to more closely reflect the population characteristics across all parameters. We contend that neither of these issues impacted adversely on the quality of the data or the subsequent results. Survey effort was not evenly distributed across interviewers, as can be seen in Fig. 1 in the ESM. However, the careful selection and training of surveyors, supported with weekly team briefings to ensure consistency in approach, as well as bi-weekly quality assurance updates, meant that interviewers met the rigorous quality assurance standards required and as evidenced in the ESM. Finally, while a range of qualitative and quantitative data on the individual and their family were collected alongside the utility survey and will undoubtedly prove useful in further analyses, it was not possible to collect all of the data we would have wished to help interpret our findings. For example, we did not collect data on medications currently used by respondents that may have impacted on their mood nor detailed biographical data on sensitive life experiences or episodes of illness that may have impacted on utility values. Such data have no role in the production of a value set and are not therefore, strictly speaking, a limitation of the study. Nevertheless, such data may be useful in subsequent work seeking to understand Irish valuations and the differences among these. However, within the context of a lengthy and demanding survey, and given interviewee fatigue, a balance must inevitably be struck between the ideal and the possible.

5 Conclusions

This paper reports an EQ-5D-5L value set for Ireland based on the health-related utility values of residents in 2015–2016. These results are useful to those evaluating new healthcare technologies in Ireland and can inform the measurement of patient-reported outcomes more generally.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Health Information and Quality Authority. Guidelines for the Economic Evaluation of Health Technologies in Ireland. Dublin: HIQA. 2014. https://www.hiqa.ie/system/files/Economic-Evaluation-Guidelines-2014.pdf. Accessed Dec 2017.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Guide to the methods of technology appraisal 2013. 2013. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg9/resources/guide-to-the-methods-of-technology-appraisal-2013-pdf-2007975843781. Accessed Dec 2017.

Dakin H, Devlin N, Feng Y, Rice N, O’Neill P, Parkin D. The influence of cost-effectiveness and other factors on NICE decisions. Health Econ. 2015;24(10):1256–71.

Paris V, Belloni A. Value in pharmaceutical pricing. OECD Health Working Papers. 2013 (63). OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k43jc9v6knx-en.

Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, Janssen M, Kind P, Parkin D, Bonsel G, Badia X. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res. 2011;20(10):1727–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x (Epub 2011 Apr 9).

Janssen MF, Pickard AS, Golicki D, Gudex C, Niewada M, Scalone L, Swinburn P, Busschbach J. Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L across eight patient groups: a multi-country study. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(7):1717–27.

Pattanaphesaj J, Thavorncharoensap M. Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to EQ-5D-3L in the Thai diabetes patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;6(13):14.

Conner-Spady BL, Marshall DA, Bohm E, Dunbar MJ, Loucks L, Al Khudairy A, Noseworthy TW. Reliability and validity of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L in patients with osteoarthritis referred for hip and knee replacement. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(7):1775–84.

Jia YX, Cui FQ, Li L, Zhang DL, Zhang GM, Wang FZ, Gong XH, Zheng H, Wu ZH, Miao N, Sun XJ, Zhang L, Lv JJ, Yang F. Comparison between the EQ-5D-5L and the EQ-5D-3L in patients with hepatitis B. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:2355–63.

Feng Y, Devlin N, Herdman M. Assessing the health of the general population in England: how do the three- and five-level versions of EQ-5D compare? Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:171.

Oppe M, Devlin NJ, van Hout B, Krabbe PF, de Charro F. A program of methodological research to arrive at the new international EQ-5D-5L valuation protocol. Value Health. 2014;17(4):445–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2014.04.002.

Devlin N, Shah K, Feng Y, Mulhern B, van Hout B. Valuing health-related quality of life: an EQ-5D-5L value set for England. Health Econ. 2017;27(1):7–22.

Xie F, Pullenayegum E, Gaebel K, Bansback N, Bryan S, Ohinmaa A, et al. A time trade-off-derived value set of the EQ-5D-5L for Canada. Med Care. 2016;54(1):98–105.

Kim SH, Ahn J, Ock M, Shin S, Park J, Luo N, Jo MW. The EQ-5D-5L valuation study in Korea. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(7):1845–52.

Purba FD, Hunfeld JAM, Iskandarsyah A, Fitriana TS, Sadarjoen SS, Ramos-Goñi JM, Passchier J, Busschbach JJV. The Indonesian EQ-5D-5L value set. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;35(11):1153–65.

Versteegh MM, Vermeulen KM, Evers SM, de Wit GA, Prenger R, Stolk EA. Dutch tariff for the five-level version of EQ-5D. Value Health. 2016;19(4):343–52.

Augustovski F, Rey-Ares L, Irazola V, Garay OU, Gianneo O, Fernández G, Morales M, Gibbons L, Ramos-Goni JM. An EQ-5D-5L value set based on Uruguayan population preferences. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(2):323–33 (Erratum in: Qual Life Res. 2016 Feb;25(2):335).

Ramos-Goñi JM, Craig B, Oppe M, Ramallo-Fariña Y, Pinto-Prades JL, Luo N, Rivero-Arias O. Handling data quality issues to estimate the Spanish EQ-5D-5L value set using a hybrid interval regression approach. Value Health. 2018;21(5):596–604.

Wong ELY, Ramos-Goñi JM, Cheung AWL, Wong AYK, Rivero-Arias O. Assessing the use of a feedback module to model EQ-5D-5L health states values in Hong Kong. Patient. 2018;11(2):235–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-017-0278-0.

Luo N, Liu G, Li M, Guan H, Jin X, Rand-Hendriksen K. Estimating an EQ-5D-5L value set for China. Value Health. 2017;20(4):662–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2016.11.016 (Epub 2017 Feb 9).

Ludwig K, Graf von der Schulenburg JM, Greiner W. German value set for the EQ-5D-5L. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(6):663–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-018-0615-8.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2017 https://www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/what-we-do/NICE-guidance/NICE-technology-appraisal-guidance/EQ-5D-5L_nice_position_statement.pdf. Accessed Feb 2018.

Olsen JA, Lamu AN, Cairns J. In search of a common currency: a comparison of seven EQ-5D-5L value sets. Health Econ Health Econ. 2018;27(1):39–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3606 (Epub ahead of print).

Stolk E, Ludwig K, Hendriksen KR, van Hout B, Ramos Gni, JM. Overview, update and lessons learned from the international EQ-5D-5L valuation work: version 2 of the EQ-5D-5L. Value Health (submitted).

Janssen BMF, Oppe M, Versteegh MM, Stolk EA. Introducing the composite time trade-off: a test of feasibility and face validity. Eur J Health Econ. 2013;14(Suppl 1):S5–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-013-0503-2.

Wong ELY, Shah K, Cheung AWL, Wong AYK, Visser M, Stolk E. Evaluation of split version and feedback module on the improvement of time trade-off data. Value Health. 2018;21(6):732–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2017.10.013.

Oppe M, van Hout B. The “power” of eliciting EQ-5D-5L values: the experimental design of the EQ-VT. EuroQol WPS 17003. https://euroqol.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/EuroQol-Working-Paper-Series-Manuscript-17003-Mark-Oppe.pdf. Accessed Feb 2018.

Haase T, Pratschke J. Optimising the sampling methodology for CSO household surveys: theoretical considerations and simulation study. 2012. http://trutzhaase.eu/wp/wp-content/uploads/R-2012-Optimising-the-Sampling-Methodology-for-CSO-Household-Surveys.pdf. Accessed Dec 2017.

Ramos-Goñi J, Craig AM, Oppe M, Van Hout B. Combining continuous and dichotomous responses in a hybrid model. Number 16002. December 2016. https://euroqol.org/wp-content/uploads/working_paper_series/EuroQol_Working_Paper_Series_Manuscript_16002_-_Juan_Ramos-Goni.pdf. Accessed 16 Sept 2017.

Solon G, Haider S, Wooldridge JM. What are we weighting for? J Hum Resour. 2015;50:301–16.

Ramos-Goñi JM, Pinto-Prades JL, Oppe M, Cabasés JM, Serrano-Aguilar P, Rivero-Arias O. Valuation and modeling of EQ-5D-5L health states using a hybrid approach. Med Care. 2017;55(7):e51–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000283.

Melrose S. Seasonal affective disorder: an overview of treatment and assessment approaches. Depress Res Treat. 2015;2015:178564. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/178564.

Tsai AC. Home foreclosure, health, and mental health: a systematic review of individual, aggregate, and contextual associations. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0123182. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0123182 (eCollection 2015).

Lloyd A. EQ-5D: moving from three levels to five. Value Health. 2018;21(1):57–8.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the work of the interview team and of Edel Murphy, the original project manager for the award. The authors are also grateful to the EuroQol Research Foundation for quality assurance provided to the survey team throughout the conduct of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CON designed the study, secured funding and prepared a first draft of the manuscript. AH and LB assisted in study design, the planning and conduct of the survey and data analyses. ND and KS supported the training of the survey team and data interpretation. JMRG supported data analysis and interpretation. DK supported data collection and analysis. All authors played a role in the review of the analysis, interpretation of the results and reviewing and recommending revisions to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by the Health Research Board under a Research Leader Award held by Ciaran O’Neill RL/2013/16. Financial support was also provided by the EuroQol Foundation.

Conflict of interest

Luke Barry, Anna Hobbins, Dan Kelleher and Ciaran O’Neill have no conflicts of interest. Nancy Devlin and Koonal Shah are employed by the Office of Health Economics, a registered charity that receives funding from a variety of sources, including the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry, and research grants and consulting fees to undertake projects relating to the EQ-5D family of instruments. Juan Manuel Ramos-Goñi is employed by the Euroqol Research Foundation and has received multiple grants from the EuroQol Research Foundation.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Hobbins, A., Barry, L., Kelleher, D. et al. Utility Values for Health States in Ireland: A Value Set for the EQ-5D-5L. PharmacoEconomics 36, 1345–1353 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-018-0690-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-018-0690-x