Abstract

Background

The inclusion of future medical costs in cost-effectiveness analyses remains a controversial issue. The impact of capturing future medical costs is likely to be particularly important in patients with cancer where costly lifelong medical care is necessary. The lack of clear, definitive pharmacoeconomic guidelines can limit comparability and has implications for decision making.

Objective

The aim of this study was to demonstrate the impact of incorporating future medical costs through an applied example using original data from a clinical study evaluating the cost effectiveness of a sepsis intervention in cancer patients.

Methods

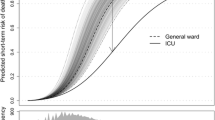

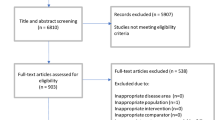

A decision analytic model was used to capture quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and lifetime costs of cancer patients from an Australian healthcare system perspective over a lifetime horizon. The evaluation considered three scenarios: (1) intervention-related costs (no future medical cost), (2) lifetime cancer costs and (3) all future healthcare costs. Inputs to the model included patient-level data from the clinical study, relative risk of death due to sepsis, cancer mortality and future medical costs sourced from published literature. All costs are expressed in 2017 Australian dollars and discounted at 5%. To further assess the impact of future costs on cancer heterogeneity, variation in survival and lifetime costs between cancer types and the implications for cost-effectiveness analysis were explored.

Results

The inclusion of future medical costs increased incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) resulting in a shift from the intervention being a dominant strategy (cheaper and more effective) to an ICER of $7526/QALY. Across different cancer types, longer life expectancies did not necessarily result in greater lifetime healthcare costs. Incremental costs differed across cancers depending on the respective costs of managing cancer and survivorship, thus resulting in variations in ICERs.

Conclusions

There is scope for including costs beyond intervention costs in economic evaluations. The inclusion of future medical costs can result in markedly different cost-effectiveness results, leading to higher ICERs in a cancer population, with possible implications for funding decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analysed during the current study are not publicly available because they include patient-level data from the clinical study. Model structure and inputs are described within the article and in the Electronic Supplementary Material. The model was developed using TreeAge Pro 2017 and is not publicly available. Enquiries regarding the model can be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Note that, in this article, the focus is on medical costs only. Future cost discussions do extend to non-medical costs, which include productivity and consumptions costs in the added life-years. A comprehensive discussion around future costs including non-medical costs has been described elsewhere [18].

References

Nyman JA. Should the consumption of survivors be included as a cost in cost–utility analysis? Health Econ. 2004;13(5):417–27.

Van Baal PH, Feenstra TL, Hoogenveen RT, Ardine de Wit G, Brouwer WB. Unrelated medical care in life years gained and the cost utility of primary prevention: in search of a ‘perfect’ cost–utility ratio. Health Econ. 2007;16(4):421–33.

Meltzer D. Accounting for future costs in medical cost-effectiveness analysis. J Health Econ. 1997;16(1):33–64.

van Baal P, Meltzer D, Brouwer W. Future costs, fixed healthcare budgets, and the decision rules of cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Econ. 2016;25(2):237–48.

Garber AM, Phelps CE. Economic foundations of cost-effectiveness analysis. J Health Econ. 1997;16(1):1–31.

Lee RH. Future costs in cost effectiveness analysis. J Health Econ. 2008;27(4):809–18.

Culyer AJ. Cost, context and decisions in health economics and cost-effectiveness analysis. York: University of York; 2018.

Grima DT, Bernard LM, Dunn ES, McFarlane PA, Mendelssohn DC. Cost-effectiveness analysis of therapies for chronic kidney disease patients on dialysis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2012;30(11):981–9.

van Baal P, Morton A, Brouwer W, Meltzer D, Davis S. Should cost effectiveness analyses for NICE always consider future unrelated medical costs? Br Med J. 2017;359:j5096.

Rappange DR, van Baal PH, van Exel NJA, Feenstra TL, Rutten FF, Brouwer WB. Unrelated medical costs in life-years gained. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(10):815–30.

Feenstra TL, van Baal PH, Gandjour A, Brouwer WB. Future costs in economic evaluation: a comment on Lee. J Health Econ. 2008;27(6):1645–9.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Guide to the methods of technology appraisal 2013; 2013. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg9/chapter/foreword. Accessed 7 May 2018.

Pharmaceutical Evaluation Branch DoH. Guidelines for preparing submissions to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC); 2017. https://pbac.pbs.gov.au/. Accessed 14 Feb 2018.

Sanders GD, Neumann PJ, Basu A, Brock DW, Feeny D, Krahn M, et al. Recommendations for conduct, methodological practices, and reporting of cost-effectiveness analyses: second panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. JAMA. 2016;316(10):1093–103.

The National Health Care Institute (Zorginstituut Nederland). Guideline for economic evaluations in healthcare; 2016. https://english.zorginstituutnederland.nl/publications/reports/2016/06/16/guideline-for-economic-evaluations-in-healthcare. Accessed 29 Apr 2018.

Stone PW, Chapman RH, Sandberg EA, Liljas B, Neumann PJ. Measuring costs in cost-utility analyses. Variations in the literature. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2000;16(1):111–24.

Olchanski N, Zhong Y, Cohen JT, Saret C, Bala M, Neumann PJ. The peculiar economics of life-extending therapies: a review of costing methods in health economic evaluations in oncology. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;15(6):931–40.

de Vries LM, van Baal PH, Brouwer WB. Future costs in cost-effectiveness analyses: past, present, future. PharmacoEconomics. 2019;37:119–30.

Kinge JM, Sælensminde K, Dieleman J, Vollset SE, Norheim OF. Economic losses and burden of disease by medical conditions in Norway. Health Policy. 2017;121(6):691–8.

Mariotto AB, Robin Yabroff K, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010–2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(2):117–28.

Kantarjian H, Steensma D, Rius Sanjuan J, Elshaug A, Light D. High cancer drug prices in the United States: reasons and proposed solutions. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(4):e208–11.

Warren JL, Yabroff KR, Meekins A, Topor M, Lamont EB, Brown ML. Evaluation of trends in the cost of initial cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(12):888–97.

Guy GP Jr, Yabroff KR, Ekwueme DU, Rim SH, Li R, Richardson LC. Economic burden of chronic conditions among survivors of cancer in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(18):2053.

Ramsey SD, Berry K, Etzioni R. Lifetime cancer-attributable cost of care for long term survivors of colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(2):440–5.

Zheng Z, Yabroff KR, Guy JGP, Han X, Li C, Banegas MP, et al. Annual medical expenditure and productivity loss among colorectal, female breast, and prostate cancer survivors in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(5):djv382.

Chang S, Long SR, Kutikova L, Bowman L, Finley D, Crown WH, et al. Estimating the cost of cancer: results on the basis of claims data analyses for cancer patients diagnosed with seven types of cancer during 1999 to 2000. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(17):3524–30.

Goldsbury DE, Yap S, Weber MF, Veerman L, Rankin N, Banks E, et al. Health services costs for cancer care in Australia: estimates from the 45 and Up Study. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):e0201552.

Blakely T, Atkinson J, Kvizhinadze G, Wilson N, Davies A, Clarke P. Patterns of cancer care costs in a country with detailed individual data. Med Care. 2015;53(4):302.

Etzioni R, Ramsey SD, Berry K, Brown M. The impact of including future medical care costs when estimating the costs attributable to a disease: a colorectal cancer case study. Health Econ. 2001;10(3):245–56.

Thursky K, Haeusler G, Teh B, Comodo D, Dean N, Brown C, et al. Using process mapping to identify barriers to effective management of sepsis in a cancer hospital: lessons for successful implementation of a whole hospital pathway. Crit Care. 2014;18(Suppl 2):P53.

Thursky K, Lingaratnam S, Jayarajan J, Haeusler GM, Teh B, Tew M, et al. Implementation of a whole of hospital sepsis clinical pathway in a cancer hospital: impact on sepsis management, outcomes and costs. BMJ Open Qual. 2018;7(3):e000355.

Soares M, Welton N, Harrison D, Peura P, Hari M, Harvey S, et al. An evaluation of the feasibility, cost and value of information of a multicentre randomised controlled trial of intravenous immunoglobulin for sepsis (severe sepsis and septic shock): incorporating a systematic review, meta-analysis and value of information analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2012;16:1–186.

Fowler RA, Hill-Popper M, Stasinos J, Petrou C, Sanders GD, Garber AM. Cost-effectiveness of recombinant human activated protein C and the influence of severity of illness in the treatment of patients with severe sepsis. J Crit Care. 2003;18(3):181–91.

Blakely T, Atkinson J, Kvizhinadze G, Nghiem N, McLeod H, Davies A, et al. Updated New Zealand health system cost estimates from health events by sex, age and proximity to death: further improvements in the age of ‘big data’. NZ Med J. 2015;128(1422):13–23.

Ministry of Health NZ. Casemix and Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) Allocation—AR-DRG v7.0. 2017. https://www.health.govt.nz/nz-health-statistics/classification-and-terminology/using-icd-10-am-achi-acs/casemix-and-diagnosis-related-group-drg-allocation-ar-drg-v70. Accessed 18 Feb 2019.

Aitken JF, Barbour A, Burmeister B, Taylor S, Walpole E, Smithers BM. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of melanoma in Australia and New Zealand. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:993–1003.

Pharoah P, Hollingworth W. Cost effectiveness of lowering cholesterol concentration with statins in patients with and without pre-existing coronary heart disease: life table method applied to health authority population. BMJ. 1996;312:1443–8.

Prescott HC, Osterholzer JJ, Langa KM, Angus DC, Iwashyna TJ. Late mortality after sepsis: propensity matched cohort study. BMJ. 2016;353:i2375.

Davis JS, He V, Anstey NM, Condon JR. Long term outcomes following hospital admission for sepsis using relative survival analysis: a prospective cohort study of 1,092 patients with 5 year follow up. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e112224.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer in Australia 2017. Canberra: AIHW; 2017. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer/cancer-in-australia-2017/contents/table-of-contents. Accessed 24 Dec 2017.

Cuthbertson BH, Elders A, Hall S, Taylor J, MacLennan G, Mackirdy F, et al. Mortality and quality of life in the five years after severe sepsis. Crit Care. 2013;17(2):R70.

Normilio-Silva K, de Figueiredo AC, Pedroso-de-Lima AC, Tunes-da-Silva G, da Silva AN, Levites ADD, et al. Long-term survival, quality of life, and quality-adjusted survival in critically ill patients with cancer. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(7):1327–37.

George B, Harris A, Mitchell A. Cost-effectiveness analysis and the consistency of decision making. Pharmacoeconomics. 2001;19(11):1103–9.

Consumer Price Index, Australia, Dec 2017. [Internet] 2017. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/6401.0. Accessed 28 Dec 2017.

OCED.Stat. Purchasing Power Parities (PPP), data and methodology. [Internet] 2017. https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=PPPGDP. Accessed 31 Dec 2017.

Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, Carswell C, Moher D, Greenberg D, et al. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS)—explanation and elaboration: a report of the ISPOR health economic evaluation publication guidelines good reporting practices task force. Value Health. 2013;16(2):231–50.

Sculpher M. Subgroups and heterogeneity in cost-effectiveness analysis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(9):799–806.

Meltzer D, Egleston B, Stoffel D, Dasbach E. Effect of future costs on cost-effectiveness of medical interventions among young adults: the example of intensive therapy for type 1 diabetes mellitus. Med Care. 2000;38:679–85.

Ramos IC, Versteegh MM, de Boer RA, Koenders JM, Linssen GC, Meeder JG, et al. Cost effectiveness of the angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor sacubitril/valsartan for patients with chronic heart failure and reduced ejection fraction in the Netherlands: a country adaptation analysis under the former and current Dutch pharmacoeconomic guidelines. Value Health. 2017;20(10):1260–9.

Manns B, Meltzer D, Taub K, Donaldson C. Illustrating the impact of including future costs in economic evaluations: an application to end-stage renal disease care. Health Econ. 2003;12(11):949–58.

Mandelblatt JS, Ramsey SD, Lieu TA, Phelps CE. Evaluating frameworks that provide value measures for health care interventions. Value Health. 2017;20(2):185–92.

Lomas J, Asaria M, Bojke L, Gale CP, Richardson G, Walker S. Which costs matter? Costs included in economic evaluation and their impact on decision uncertainty for stable coronary artery disease. PharmacoEconomics Open. 2018;2:403–13.

Ioannidis JP, Garber AM. Individualized cost-effectiveness analysis. PLoS Med. 2011;8(7):e1001058.

Ramaekers BL, Joore MA, Grutters JP. How should we deal with patient heterogeneity in economic evaluation: a systematic review of national pharmacoeconomic guidelines. Value Health. 2013;16(5):855–62.

Leung W, Kvizhinadze G, Nair N, Blakely T. Adjuvant trastuzumab in HER2-positive early breast cancer by age and hormone receptor status: a cost-utility analysis. PLoS Med. 2016;13(8):e1002067.

Weinstein MC, Manning W. Theoretical issues in cost-effectiveness analysis. J Health Econ. 1997;16(1):121–8.

Gros B, Soto Álvarez J, Ángel Casado M. Incorporation of future costs in health economic analysis publications: current situation and recommendations for the future. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;15(3):465–9.

van Baal PH, Feenstra TL, Polder JJ, Hoogenveen RT, Brouwer WB. Economic evaluation and the postponement of health care costs. Health Econ. 2011;20(4):432–45.

Capocaccia R, Gatta G, Dal Maso L. Life expectancy of colon, breast, and testicular cancer patients: an analysis of US-SEER population-based data. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(6):1263–8.

de Oliveira C, Pataky R, Bremner KE, Rangrej J, Chan KK, Cheung WY, et al. Phase-specific and lifetime costs of cancer care in Ontario, Canada. BMC Cancer. 2016;16(1):809.

Lang K, Lines LM, Lee DW, Korn JR, Earle CC, Menzin J. Lifetime and treatment-phase costs associated with colorectal cancer: evidence from SEER-Medicare data. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(2):198–204.

Talmor D, Greenberg D, Howell MD, Lisbon A, Novack V, Shapiro N. The costs and cost-effectiveness of an integrated sepsis treatment protocol. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(4):1168–74.

Suarez D, Ferrer R, Artigas A, Azkarate I, Garnacho-Montero J, Gomà G, et al. Cost-effectiveness of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign protocol for severe sepsis: a prospective nation-wide study in Spain. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37(3):444–52.

Jones AE, Troyer JL, Kline JA. Cost-effectiveness of an emergency department based early sepsis resuscitation protocol. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(6):1306.

van Baal PH, Wong A, Slobbe LC, Polder JJ, Brouwer WB, de Wit GA. Standardizing the inclusion of indirect medical costs in economic evaluations. Pharmacoeconomics. 2011;29(3):175–87.

Brown ML, Riley GF, Schussler N, Etzioni R. Estimating health care costs related to cancer treatment from SEER-Medicare data. Med Care. 2002;40:104–17.

Cobiac LJ, Tam K, Veerman L, Blakely T. Taxes and subsidies for improving diet and population health in Australia: a cost-effectiveness modelling study. PLoS Med. 2017;14(2):e1002232.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Health system expenditure on disease and injury in Australia, 2004–05. Canberra: AIHW; 2010. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/health-welfare-expenditure/expenditure-disease-injury-2004-05/contents/table-of-contents. Accessed 24 Oct 2018.

Meltzer D, Johannesson M. Inconsistencies in the” societal perspective” on costs of the panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. Med Decis Making. 1999;19(4):371–7.

Danai PA, Moss M, Mannino DM, Martin GS. The epidemiology of sepsis in patients with malignancy. Chest. 2006;129(6):1432–40.

Briggs A, Sculpher M, Claxton K. Decision modelling for health economic evaluation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Professor Tony Blakely for his helpful comments and input into an earlier version of the paper.

Funding

This study was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC)-funded Centre for Improving Cancer Outcomes Through Enhanced Infection Services (1116876). Michelle Tew is jointly supported by the NHMRC-funded Centre for Research Excellence in Total Joint Replacement (1116325) and Centre for Improving Cancer Outcomes Through Enhanced Infection Services (1116876), and a Melbourne Research Scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and planning of the work. Michelle Tew developed the cost-effectiveness model and conducted the analyses with input from Kim Dalziel and Philip Clarke. Karin Thursky led the clinical study and provided clinical evidence input and resource use data to estimate costs of the intervention. Michelle Tew led the writing of this manuscript and was supervised by all authors. All authors participated in the discussion that led to this paper and in the revision of all drafts. All authors approved the final version submitted for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Michelle Tew, Philip Clarke, Karin Thursky and Kim Dalziel have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the contents of this article.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tew, M., Clarke, P., Thursky, K. et al. Incorporating Future Medical Costs: Impact on Cost-Effectiveness Analysis in Cancer Patients. PharmacoEconomics 37, 931–941 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-019-00790-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-019-00790-9