Abstract

The EQ-5D-Y-3L is a generic, health-related, quality-of-life instrument for use in younger populations. Some methodological studies have explored the valuation of children’s EQ-5D-Y-3L health states. There are currently no published value sets available for the EQ-5D-Y-3L that are appropriate for use in a cost-utility analysis. The aim of this article was to describe the development of the valuation protocol for the EQ-5D-Y-3L instrument. There were several research questions that needed to be answered to develop a valuation protocol for EQ-5D-Y-3L health states. Most important of these were: (1) Do we need to obtain separate values for the EQ-5D-Y-3L, or can we use the ones from the EQ-5D-3L? (2) Whose values should we elicit: children or adults? (3) Which valuation methods should be used to obtain values for child’s health states that are anchored in Full health = 1 and Dead = 0? The EuroQol Research Foundation has pursued a research programme to provide insight into these questions. In this article, we summarized the results of the research programme concluding with the description of the features of the EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation protocol. The tasks included in the protocol for valuing EQ-5D-Y-3L health states are discrete choice experiments for obtaining the relative importance of dimensions/levels and composite time-trade-off for anchoring the discrete choice experiment values on 1 = Full Health and 0 = Dead. This protocol is now available for use by research teams to generate EQ-5D-Y-3L value sets for their countries allowing the implementation of a cost-utility analysis for younger populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

This article reports an international valuation protocol for the EQ-5D-Y-3L instrument |

The international protocol is a two-step approach based on an online discrete choice experiment (Step 1) plus a face-to-face composite time-trade-off exercise (Step 2) |

Following the reported protocol, researchers can develop EQ-5D-Y-3L value sets in their respective countries to allow a cost-utility analysis in a child/adolescent population |

1 Introduction

There are several preference-based instruments for measuring health-related quality of life in children, including AHUM [1], AQoL-6D [2], CHU9D [3], EQ-5D-Y [4], HUI2 [5], HUI3 [6], QWB [7], 16D [8] and 17D [9]. For a recent review, see Rowen et al. [10]. The EQ-5D-Y-3L is the three-level version of one of those instruments, the EQ-5D-Y. It was developed by the EuroQol Group, for use in younger populations (i.e. children aged 8–15 years) [4, 11]. It was adapted from the original EQ-5D-3L instrument using appropriate wording for this age group. One of the advantages of the EQ-5D family of instruments is the availability of value sets to accompany them, which provide utilities for use in a cost-utility analysis. In the absence of EQ-5D-Y-3L value sets, some authors have used EQ-5D-3L value sets to calculate utilities for the EQ-5D-Y-3L [12, 13].

A few methodological studies have explored the valuation of child health states (HS) defined by the EQ-5D-Y-3L. For example, Wu et al. produced values based on Canadian children’s self-reported health using the EQ-5D-Y-3L [14]. They modelled the relationship between children’s overall assessment of their health on the visual analogue scale (VAS) and their responses to the self-classifier (where they indicated their level of problems for each of the five dimensions). However, as the relative position of Dead is not included in self-reported health, this method cannot produce values on the quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) scale, which by convention is anchored at 1 = Full health and 0 = Dead.

Kind et al. elicited stated preferences for hypothetical EQ-5D-Y-3L HS using VAS valuation methods. However, while a VAS valuation can include tasks to anchor ratings onto the QALY scale, the Kind et al. study did not include such tasks [15]. The study aimed to test the effect on values of three different perspectives from which HS were evaluated: own health, third-person adult’s health and third-person 10-year-old child’s health. The authors concluded that values for adults’ HS (own health) were higher than values (also called utilities) for equivalent HS described as applying to a 10-year-old child. As the observed values were different, the corollary was that applying EQ-5D-3L values to EQ-5D-Y-3L HS is inappropriate.

Craig et al. developed a methodological value set for the EQ-5D-Y-3L for the US population using a discrete choice experiment (DCE), which included a duration attribute in the HS description (DCE + Duration) [16]. However, that value set, while showing further evidence of differences between values for child and adult HS, has been criticised for its unusual characteristics, notably, having a value of − 9.03 for the worst possible HS (compared with a value of − 0.102 for the corresponding HS on the EQ-5D-3L reported by Shaw et al. in another US study [17]).

At the time of writing, there are currently no published value sets available for the EQ-5D-Y-3L that are appropriate for use in QALY calculations [11] and, as noted above, it seems inappropriate to apply values for the (adult) EQ-5D-3L. There is therefore a need for specific value sets for the EQ-5D-Y-3L instrument that allow the calculation of QALYs to support the use of the instrument in economic evaluations. The EuroQol Research Foundation has pursued a programme of methodological research to inform an international protocol for producing values for EQ-5D-Y-3L.

The aim of this article is to describe the development of the valuation protocol for the EQ-5D-Y-3L instrument. We start by describing the research studies conducted as part of the EuroQol research programme leading to the development of the valuation protocol and the results from these studies. We then provide a detailed description of the features of the valuation protocol.

2 Overview of Methodological Research

2.1 Design of the Methodological Research Programme

There were a number of research questions that needed to be answered prior to development of a valuation protocol for EQ-5D-Y-3L HS. Key questions included: (1) Do we need to obtain separate values for the EQ-5D-Y-3L, or can we use those from the EQ-5D-3L? (2) Whose preferences should we elicit: children or adults? (3) Which valuation methods should be used to obtain values for child HS that can be used to calculate QALYs?

As noted above, results from Kind et al. [15] and Craig et al. [16] suggested that values for child HS were different than those for adult HS, but this needed to be confirmed for stated preference methods that are anchored on the QALY scale. Given the complex and abstract nature of the valuation tasks, it is unclear whether it is feasible for children to carry out these tasks. Further, the need to explicitly compare HS with “dead” for anchoring purposes raises ethical concerns regarding the involvement of children in such studies. Ultimately, whose preferences should be used (adults or children) in valuing EQ-5D-Y-3L (or indeed any utility-weighted paediatric PRO) is a normative question. For the purpose of the methodological research programme, it was decided that the taxpayer perspective used for valuing adult HS in previous EQ-5D valuation studies should also be used when valuing child HS because of the use of these values to inform HTA and resource allocation. However, to understand whether the decision to seek adult values for EQ-5D-Y-3L would have important consequences (e.g. for HTA decisions), a study was undertaken to determine whether preferences elicited from children differ from those elicited from adults for child HS.

The decision to adopt a taxpayer perspective necessarily led to another question: if adults are to value child HS, how should valuation tasks be framed? Consistent with previous research [15, 16], a decision was taken to frame the questions around hypothetical HS for a 10-year-old child. Acknowledging that the decision to focus on a 10-year-old child is somewhat arbitrary, our aim was to confirm the Kind et al. results [15]; therefore, changing the framing would introduce a confounding factor that may limit our ability to compare and interpret the results.

Given the extensive experience with using the second version of the standardised valuation protocol for the EQ-5D-5L [18, 19], it was decided to adapt the valuation protocol and accompanying software (EQ-VT) for piloting an EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation. This protocol involves two valuation techniques: the composite time-trade-off (C-TTO) [20], which uses conventional time-trade-off for the better than dead HS and lead-time time-trade-off (TTO) for the worse than dead HS and the DCE [21].

Once these decisions were made, we were in the position to test whether adults’ values for child HS differ from adults’ values for adult HS. However, given the differences in wording between the EQ-5D-3L and the EQ-5D-Y-3L, answering that question required a study design that could isolate (a) how the difference in wording between the two instruments affects the values and (b) how the difference in perspective (adult vs child) affects the values. All these decisions fed into the design of the first pilot study, called the ‘multi-country EQ-VT pilot study for the EQ-5D-Y-3L’, which is described below.

2.2 Multi-Country EQ-VT Pilot Study for the EQ-5D-Y-3L

The methodology implemented was based, with some adaptations, on the standardised protocol used for the valuation of EQ-5D-5L [22], i.e. including the aforementioned C-TTO and DCE, but adding a comparison with dead to the DCE exercise (DCE + Dead). The results clearly confirmed that EQ-5D-3L value sets should not be applied to EQ-5D-Y-3L HS (Table 1).

The results also meant that new issues emerged. In contrast to the earlier VAS and DCE + Duration valuation studies (which yielded lower values for child HS than for adult HS), the C-TTO approach produced higher values for child HS compared with adult HS. This raised questions about the reasons for this seemingly contradictory finding and led to the view that the use of the C-TTO valuation technique in valuing child HS warranted further research. One possible explanation is that a strong preference for length of life in children leads to an unwillingness to trade off time in the TTO task and may lead to a lack of accuracy in measuring the relative importance of the health dimensions. A DCE (without a duration attribute) is not affected by time preference, making the approach attractive. In the light of this evidence, the EuroQol Group decided to test the two-step valuation approach as follows: the relative importance of EQ-5D-Y-3L dimensions can be estimated by a DCE; but as the DCE results are on a latent (undefined) scale, further research is needed to identify appropriate methods to anchor the DCE results. These decisions led to three further studies that were conducted in parallel in the UK and The Netherlands: a latent scale DCE study; a DCE + Duration study and an anchoring methods study. Details of each are provided below.

2.3 Discrete Choice Experiment (DCE) + Duration Study in The Netherlands

This research centred on analysing the age dependency of HS values, while accounting for possible differences in time preferences across groups (Table 1). Conclusions from this research were in line with those reported in the multi-country EQ-VT pilot study. However, there may be limits to the generalisability of these results to other jurisdictions because the multi-country EQ-VT pilot study also reported different preferences for HS in children and in adults, but the same results was not found in other countries [23]. As a possible explanation for the international differences, the authors point out that Dutch attitudes about trade-offs between length and quality of life may be influenced by (or reflected in) their euthanasia policy.

2.4 Latent Scale DCE Study in the UK

An international research team designed this study to obtain latent scale DCE utilities from the adult general population from the perspective of a 10-year-old child in the UK [23] (Table 1). The format of the DCE was the same as that used for DCE tasks in the multi-country EQ-VT pilot study [22]. A Bayesian efficient design was created to identify the pairs of HS included in the DCE. The modelling exercise consisted of testing different approaches for dealing with heterogeneity. However, as these results alone were not enough for producing a value set comprising anchored utilities for QALY calculations because its results are not on the 1 = Full health to 0 = Dead scale, the anchoring study was conducted.

2.5 Anchoring Study in the UK

The team assessed values for EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-Y-3L HS using four preference elicitation techniques: VAS, DCE + Duration, lag-time TTO and the location-of-dead element from the newly developed, personal utility function approach [24]. A within-subject study design was used [25] (Table 1). While showing lower values for the adult perspective than for the child perspective, most of the same respondents indicated (in a separate question framed as: “How do you think a health care system with a limited budget should prioritise resources?”) that “The health system should give equal priority to the treatment of adults and children” [25]. Further, based on the results, the authors discussed the circumstances under which the use of values in a cost-utility analysis requires that adult and child HS values are commensurable, i.e. where treatment starts in childhood and is maintained during the transition into adulthood and later in life.

3 Key Considerations Arising from the Research Programme

The research programme described above allowed the EuroQol Group to clarify its position in relation to a number of important methodological questions. The key findings are summarized below (Table 2).

3.1 Are Adults’ Values for Child Health States Different from their Values for Adult HS? Are the Differences in Wording between the Instruments (EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-Y-3L) Affecting Values?

Based on our research, child HS values are different from adult HS values and the wording of the instruments affects values. Although some authors have applied EQ-5D-3L value sets to calculate utilities for the EQ-5D-Y-3L [12, 13], this research programme confirmed that values for EQ-5D-Y-3L HS (child perspective) are different than values for EQ-5D-3L HS (adult perspective) [22]. In fact, researchers reported an interactive effect between wording of the instrument and perspective on values [22]. These results confirmed that EQ-5D-3L value sets should not be used to assign values to EQ-5D-Y-3L HS.

3.2 Is a DCE a Suitable and Valid Approach to Obtain the Relative Importance of the EQ-5D-Y-3L Dimensions?

A DCE is suitable and feasible for use in valuing child HS [23]. A DCE is becoming more widely used in valuation research because of its advantages in terms of lower cost and speed of data collection [26,27,28,29]. A DCE also has the advantages of being less cognitively challenging and less burdensome to administer than other alternatives [28, 29]. In addition, this method avoids issues around the importance of the time attribute as is the case with any variant of TTO or DCE + Duration, and it does not require consideration of dead. Nevertheless, this can also be seen as a disadvantage because the lack of consideration of dead or the duration of the HS leads to the generation of relative preference weights on an undefined scale that cannot be used to calculate QALYs [28,29,30]. Consequently, a DCE seems suitable for obtaining accurate information on the relative importance of the different dimensions/levels but the problem of generating an anchored value set for the EQ-5D-Y-3L instrument is still not fully solved.

3.3 Can EQ-5D-Y-3L DCE Latent Scale Values be Anchored onto the 1 = Full Health to 0 = Dead Scale?

The research programme concluded that combining the latent scale value set with data from one of the four preference elicitation methods tested in the anchoring study is feasible, with multiple methods shown to be valid and feasible for this purpose [28, 30]. Thus, and to maintain consistency with the tradition of using TTO in the valuation of EQ-5D instruments, it was decided to continue using C-TTO for anchoring purposes. In this approach, it is possible to generate anchored utility values suitable for estimating QALYs.

4 EQ-5D-Y-3L Valuation Protocol

Prior to describing details of the experimental design, based on the output of the research programme, there are three key features of the protocol to be noted:

- (1)

The values will be obtained from a sample of adults from the general population. As noted above, this follows the taxpayer perspective and avoids possible ethical issues associated with consideration of dead by a sample of children.

- (2)

The framing of the valuation task is: “Considering your views about a 10-year-old child, what do you prefer?”.

- (3)

The protocol has a two-step approach, first, using an online DCE to generate the latent scale values. Then, as a second step, obtaining C-TTO values, via face-to-face interviews, as a means of anchoring the DCE results. Note that C-TTO studies are not recommended to be conducted online, while we have had good experience with conducting online DCE surveys. As there is no need to have the same sample complete both valuation tasks when the purpose is to use C-TTO information only for anchoring the DCE latent scale results, it would be more efficient to separate the samples and conduct one online survey and another face-to-face interview exercise.

The key features of the protocol are described in Table 3. Although the basis for developing the EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation protocol was the valuation protocol of the EQ-5D-5L [18, 19], it is important to note the following differences between the protocols:

- (1)

In the EQ-5D-5L protocol, adult respondents value HS considering their own health. In the EQ-5D-Y-3L protocol, adult respondents value health considering the health of a hypothetical 10-year-old child (see Figs. 1 and 2).

- (2)

While in the EQ-5D-5L valuation protocol the DCE was introduced as a valuation technique that was complementary to the C-TTO, in the EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation protocol, each valuation technique has its own purpose. The purpose of the DCE is to determine the relative importance of dimensions/levels and the role of C-TTO is restricted to providing the anchors at 1 = Full health and 0 = Dead as required to support the use of the values in an economic evaluation (cost-utility analysis).

- (3)

While in the EQ-5D-5L protocol, all respondents had to complete both C-TTO and DCE tasks in a face-to-face setting, in the EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation protocol, there are two different samples. One sample will complete a set of DCE tasks in an online environment and another sample will complete a set of TTO tasks in a face-to-face setting. Both samples should be as representative of the relevant country’s population (i.e. in terms of sociodemographic characteristics) as possible.

- (4)

The number of tasks per respondent in the EQ-5D-5L valuation protocol was ten C-TTO HS and seven DCE pairs, allowing the estimation of models for both sets of data. In the EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation protocol, each respondent in the online survey will complete 15 DCE pairs out of a design that includes 150 pairs distributed over ten blocks (Electronic Supplementary Material) and each face-to-face respondent will complete ten C-TTO tasks out of a design of ten HS included in a single block (Table 3). This will allow DCE modelling and mapping modelling but not TTO-only modelling because there are not enough HS included in the TTO design for this purpose.

Table 3 Summary of the EQ-5D-Y-3L protocol

4.1 DCE Design of the EQ-5D-Y-3L Protocol

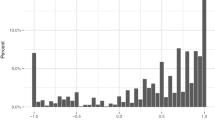

The experimental design of the DCE was developed for the latent scale DCE study in the UK. This design, as described above, used a blocked design with ten blocks and 15 pairs per block (see Fig. 1 for an example of a DCE task). To reduce attribute non-attendance, the design of DCE used an overlap in two domains. Although not mandatory, it is recommended that the design is updated using Bayesian methods after a soft launch of data collection, see [23] for further details (Table 4).

There is no single best approach to determine the sample size needed for a DCE with our specific design criteria. Two rules of thumb for a minimum sample size have been proposed in the literature based on the number of observations per pair. Lancsar and Louviere suggest a minimum of 20 observations per pair [21], while Hensher and colleagues recommend a minimum of 30 observations per pair [31]. To ensure having enough power to accurately estimate the model parameters, we decided to double the average of the two rules of thumb and use 50 observations per pair as a minimum for the DCE in the EQ-5D-Y-3L protocol. Because we have a design comprising ten blocks, this would require a minimum of 500 individual respondents. However, given the low marginal cost of including extra online respondents compared with the fixed cost of implementing the survey, we recommend doubling the minimum sample size to 1000.

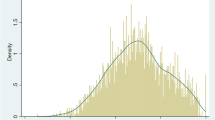

4.2 Composite Time-Trade-Off Element of the EQ-5D-Y-3L Protocol

The use of C-TTO (see Fig. 2 for an example of the C-TTO task) for anchoring DCE results requires that the design include the worst HS in the descriptive system (33,333). However, more HS were added with the aim of avoiding scaling issues within C-TTO [24]. It is important to remark here that this C-TTO design corresponds to a minimum requirement but does not prevent researchers from adding more HS to this design. The EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation protocol exploits the possibility of linking C-TTO and DCE data, e.g. mapping or just using the C-TTO value of the worst possible HS to anchor the latent scale value set. Research teams can choose to collect more TTO data, by either increasing the sample size or increasing the number of HS included in the design; however, generating a TTO-only based value set is not recommended because of concern about the aforementioned impact of time preference when adults value child HS.

To estimate the minimum sample size required for the C-TTO element of the protocol, we have used previous calculations for the EQ-5D-5L protocol, where the assumption was made that the value of any HS should be estimated with a given standard error of 0.01 [33, 34]. In the EQ-5D-5L valuation protocol, there was a need of 100 observations. In the case of the EQ-5D-Y-3L protocol, we have estimated that 200 observations are required to reduce the variability to 0.005.

5 Discussion

While an evidence-based EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation protocol was described here, there were still several points that need further discussion and/or research. Clear examples were the decision about who should value the child HS, where we decided to adopt a taxpayer perspective and the choice of how to frame the eliciting question, which may still seem arbitrary. This means that this protocol is subject to future improvements like any other scientific product.

Regarding the framing of the questions, child HS valuations in other instruments [10] suggest that values differ across paediatric ages implying that multiple value sets may be needed. However, the DCE + Duration study conducted in The Netherlands, indicated that HS values were similar between a 10- or a 15-year-old child. Given that the EQ-5D-Y-3L instrument is recommended to be used on a population in the age range of 8–15 years, it seemed appropriate to keep with our selected framing of a 10-year-old child for developing a unique country-specific EQ-5D-Y-3L value set. It should be noted that the EuroQol Group does not normally generate age-specific value sets for different adult age subgroups (or indeed any other subgroups) [35, 36]. However, as preferences regarding the health of 10-year-old children may differ from preferences regarding the health of children or adolescents of other ages, further research is needed on this topic.

With respect to whom should value the child HS and our choice of adopting the taxpayer perspective, this is a normative discussion rather than a scientific discussion. There are some points that should be considered: (1) in the same way that most countries do not allow people aged under 18 years to vote for which political party should govern the country, it may be viewed as inappropriate to allow a population in the age range of 8–15 years to decide about the population health; (2) when developing value sets, the valuation task must include consideration of dead to be able to calculate QALYs. It could be considered ethically inappropriate to apply those tasks to a young population of respondents. In addition, obtained values could be inaccurate owing to a possible misunderstanding of the tasks; and (3) our taxpayer approach is in line with what other child health valuation researchers have done, for example with valuation of the CHU9D instrument [37], indeed, it could be considered fair as it is taxpayers who funding healthcare.

In comparison with a recent child HS valuation study conducted by Rowen et al. [29], we differ from the selected valuation methods. They used a DCE + Duration approach and tested it in The Netherlands (as noted above, this is a country that may hold somewhat unique preferences regarding life duration trade-offs). We have shown in our anchoring study that this approach did not work as well in the UK.

Finally, potential users of the future EQ-5D-Y-3L value sets may wish to combine adult and child values in the estimation of QALYs, or they may wish to know whether the current cost-effectiveness threshold values determined in some countries are valid to decide if a treatment is cost effective when the cost-utility analysis uses an EQ-5D-Y-3L value set. Because adult EQ-5D value sets (either 3L or 5L) are not comparable with EQ-5D-Y value sets, it is advised that they are not combined when calculating QALYs. Instead, we recommended that different cost-effectiveness thresholds values should be applied.

6 Conclusions

In this article, we have presented an international evidence-based protocol for valuing EQ-5D-Y-3L HS to be used in the age range of 8–15 years. This protocol is now available for use by research teams to generate EQ-5D-Y-3L value sets for their countries, thereby allowing the implementation of a cost-utility analysis to evaluate healthcare interventions for younger populations.

References

Beusterien KM, Yeung JE, Pang F, Brazier J. Development of the multi-attribute Adolescent health utility measure (AHUM). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:102.

Richardson J, Day N, Peacock S, et al. Measurement of the quality of life for economic evaluation and the assessment of quality of life (AQoL) mark 2 instrument. Aust Econ Hist Rev. 2004;37:62–88.

Stevens KJ. Assessing the performance of a new generic measure of health related quality of life for children and refining it for use in health state valuation. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2011;9(3):157–69.

Wille N, Badia X, Bonsel G, et al. Development of the EQ-5D-Y: a child-friendly version of the EQ-5D. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(6):875–86.

Torrance G, Feeny D, Furling W, et al. Multiattribute utility function for a comprehensive health status classification system: Health Utilities Index Mark 2. Med Care. 1996;34:702–22.

Feeny D, Furlong W, Torrance GW, Goldsmith CH, Zhu Z, DePauw S, et al. Multiattribute and single-attribute utility functions for the health utilities index mark 3 system. Med Care. 2002;40(2):113–28.

Seiber WJ, Groessl EJ, David KM, Ganiats TG, Kaplan RM. Quality of well being self-administered (QWB-SA) scale: user’s manual. San Diego: Health Services Research Center, University of California; 2008.

Apajasalo M, Sintonen H, Holmberg C, et al. Quality of life in early adolescence: a sixteen-dimensional health-related measure (16D). Qual Life Res. 1996;5:205–11.

Apajasalo M, et al. Quality of life in pre-adolescence: a 17-dimensional health-related measure (17D). Qual Life Res. 1996;5:532–8.

Rowen D, Rivero-Arias O, Devlin N, Ratcliffe J. Review of valuation methods of preference-based measures of health for economic evaluation in child and adolescent populations: where are we now and where are we going? Pharmacoeconomics. 2020;38(4):325–40.

EuroQol. EQ-5D-Y user guide. Basic information on how to use the EQ-5D-Y instrument. Version 1.0. Rotterdam: EuroQol Research Foundation; 2014. Available from: https://euroqol.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/EQ-5D-Y_User_Guide_v1.0_2014.pdf. [Accessed 7 Apr 2020].

Griebsch I, Coast J, Brown J. Quality-adjusted life-years lack quality in paediatric care: a critical review of published cost-utility studies in child health. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e600–e608608.

Zimovetz EA, Beard SM, Hodgkins P, Bischof M, Mauskopf JA, Setyawan J. A cost-utility analysis of lisdexamfetamine versus atomoxetine in the treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and inadequate response to methylphenidate. CNS Drugs. 2016;30(10):985–96.

Wu XY, Ohinmaa A, Johnson JA, Veugelers PJ. Assessment of children’s own health status using visual analogue scale and descriptive system of the EQ-5D-Y: linkage between two systems. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(2):393–402.

Kind P, Klose K, Gusi N, et al. Can adult weights be used to value child health states? Testing the influence of perspective in valuing EQ-5D-Y. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:2519–39.

Craig BM, Greiner W, Brown DS, Reeve BB. Valuation of child health-related quality of life in the United States. Health Econ. 2016;25(6):768–77.

Shaw JW, Johnson JA, Coons SJ. US valuation of the EQ-5D health states: development and testing of the D1 valuation model. Med Care. 2005;43:203–20.

Oppe M, Devlin NJ, van Hout B, et al. A program of methodological research to arrive at the new international EQ-5D-5L valuation protocol. Value Health. 2014;17:445–53.

Stolk E, Ludwig K, Rand K, et al. Overview, update, and lessons learned from the international EQ-5D-5L valuation work: version 2 of the EQ-5D-5L valuation protocol. Value Health. 2019;22:23–30.

Janssen BM, Oppe M, Versteegh MM, et al. Introducing the composite time trade-off: a test of feasibility and face validity. Eur J Health Econ. 2013;14(Suppl. 1):S5–13.

Lancsar E, Louviere J. Conducting discrete choice experiments to inform healthcare decision making. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(8):661–77.

Kreimeier S, Oppe M, Ramos-Goñi JM, et al. Valuation of EuroQol five-dimensional questionnaire, youth version (EQ-5D-Y) and EuroQol five-dimensional questionnaire, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L) health states: the impact of wording and perspective. Value Health. 2018;21(11):1291–8.

Mott DJ, Shah K, Ramos-Goñi J, et al. Valuing EQ-5D-Y health states using a discrete choice experiment: do adult and adolescent preferences differ? OHE research paper. London: Office of Health Economics; 2019. Available from: https://www.ohe.org/publications/valuing-eq-5d-y-health-states-using-discrete-choice-experiment-do-adult-and-adolescent. [Accessed 7 Apr 2020].

Devlin NJ, Shah KK, Mulhern BJ, et al. A new method for valuing health: directly eliciting personal utility functions. Eur J Health Econ. 2019;20(2):257–70.

Shah KK, Ramos-Goñi JM, Kreimeier S, Devlin NJ. Anchoring latent scale values for the EQ-5D-Y at 0 = dead. OHE research paper. London: Office of Health Economics; 2020. Available from: https://www.ohe.org/publications/anchoring-latent-scale-values-eq-5d-y-0-dead. [Accessed 7 Apr 2020].

Wang B, Chen G, Ratcliffe J, Ali Afzali HH, Giles L, Marshall H. Adolescent values for immunisation programs in Australia: a discrete choice experiment. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(7):e0181073.

Mansfield C, Sikirica M, Pugh A, Poulos C, Unmuessig V, Morano R, et al. Patient preferences for attributes of type 2 diabetes mellitus medications in Germany and Spain: an online discrete-choice experiment survey. Diabetes Ther. 2017;8:1365–78.

Stolk EA, Oppe M, Scalone L, Krabbe PF. Discrete choice modelling for the quantification of health states: the case of the EQ-5D. Value Health. 2010;13(8):1005–133.

Krabbe PF, Devlin NJ, Stolk EA, Shah KK, Oppe M, van Hout B, et al. Multinational evidence of the applicability and robustness of discrete choice modelling for deriving EQ-5D-5L health-state values. Med Care. 2014;52(11):935–43.

Ramos-Goni JM, Rivero-Arias O, Errea M, et al. Dealing with the health state ‘dead’ when using discrete choice experiments to obtain values for EQ-5D-5L heath states. Eur J Health Econ. 2013;14(Suppl. 1):33–42.

Hensher DA, Rose JM, Greene WH. Applied choice analysis: a primer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

Morrison GC, Neilson A, Malek M. Improving the sensitivity of the time trade-off method: results of an experiment using chained TTO questions. Health Care Manag Sci. 2002;5:53–61.

Ramos-Goni JM, Pinto-Prades JL, Oppe M, Cabases JM, Serrano-Aguilar P, Rivero-Arias O. Valuation and modeling of EQ-5D-5L health states using a hybrid approach. Med Care. 2017;55(7):e51–e5858.

Oppe M, van Hout B. The “power” of eliciting EQ-5D-5L values: the experimental design of the EQ-VT. EuroQol Working Paper Series. Number 17003. October 2017. Available from: https://euroqol.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/EuroQol-Working-Paper-Series-Manuscript-17003-Mark-Oppe.pdf. [Accessed 7 Apr 2020].

Cubi-Molla P, Shah K, Garside J, Herdman M, Devlin N. A note on the relationship between age and health-related quality of life assessment. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(5):1201–5.

Robinson A, Parkin D. Recognising diversity in public preferences: the use of preference sub-groups in cost-effectiveness analysis. A response to Sculpher and Gafni. Health Econ. 2002;11(7):649–51.

Rowen D, Mulhern B, Stevens K, Vermaire JH. Estimating a Dutch value set for the pediatric preference-based CHU9D using a discrete choice experiment with duration. Value Health. 2018;21(10):1234–42.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the Chair of the EuroQol Younger Population Working Group, Wolfgang Greiner and the Chair of the EuroQol Executive Committee, Jan van Busschbach for their contribution in the scientific discussion that led to the described protocol.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JMRG, ND, MO and ES designed the protocol prototype, all other authors have participated or leaded at least one of the methodological studies conducted to obtain the protocol. JMRG and MO drafted the initial version of the manuscript all other authors have revised the initial version providing valuable content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The study was financially supported by The EuroQol Research Foundation. Specifically, the EuroQol Group funded all methodological studies described in this article as well as partially funded the preparation of this article.

Conflict of Interest

Juan M. Ramos-Goñi, Mark Oppe, Elly Stolk, Koonal Shah, Simone Kreimeier, Oliver Rivero-Arias and Nancy Devlin report no conflicts of interest for the past 3 years. Although not a conflict of interest, we report that all authors of this article are either members of the EuroQol Group or are directly employed by the EuroQol Research Foundation.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ramos-Goñi, J.M., Oppe, M., Stolk, E. et al. International Valuation Protocol for the EQ-5D-Y-3L. PharmacoEconomics 38, 653–663 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-020-00909-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-020-00909-3