Abstract

Worldwide, the social protection programs have become a key tool for policymakers. These programs are executed to achieve multiple objectives such as fighting poverty and hunger, and increasing the resilience of the poor and vulnerable groups towards various shocks. Recently, with the rapid spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, many countries started to implement social protection programs to eliminate the negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis and enhance community resilience. This study aims to explore the current implementation of social protection programs during the COVID-19 pandemic in the most affected countries as well as to provide learned lessons from countries that had not previously considered implementing social protection programs up until the COVID-19 crisis. This review was carried out by searching through WOS, Google Scholar, ILO, World Bank reports, and Aljazeera Television. The search was conducted over literature and systematic reviews on the implementation of social protection programs during previous pandemic crises and especially in the current COVID-19 pandemic. The findings revealed that social protection programs become a flexible and strategic tool to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, the study highlighted a lack of comprehensive strategy amongst the countries in executing the social protection programs to respond to COVID-19. Finally, the study concluded with some learned lessons and implications for the practitioners and policymakers in managing future pandemics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Early at the beginning of 2020, the WHO declared the new epidemic namely “the novel coronavirus disease 2019” as a worldwide public health emergency (Wu et al. 2020). On February 11, 2020, China accounted for about 42,708 infected cases and by 27 July 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic spread over about 216 territories with a total of confirmed cases estimated at 16,114,449 and with about 646,641deaths. The most affected countries are the USA, Brazil, India, Russian, Peru, Chile, UK, Mexico, Spain, Iran, Pakistan, and Italy (WHO 2020).

According to the increasing spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, many countries applied different measures such as closing the airports, implementing bans for some commodities and medical products, reducing work time, home quarantine, and curfews. These measures affect the country’s economic sectors and risk to increase social inequality and poverty. Hence, many countries start to implement various SPP to cope with the negative socioeconomic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Initially, social protection programs (SPP) have been executed by many countries to fight hunger and poverty. Therefore, Andrews et al. (2018) and Hidrobo et al. (2018) highlighted that the SPP play key roles in supporting the poor to get out of poverty and hunger. Previously, many authors indicated that the SPP address chronic poverty, reduce social inequality, and enhance the livelihood of the poor (Alderman and Yemtsov 2012). Accordingly, SPP spread rapidly in Africa where the number of SPP beneficiaries tripled in the last 15 years (Beegle et al. 2018). For instance, Handa et al. (2018) emphasized that the delivery of cash transfers has multiplier effects on the economy of low-income countries.

Moreover, Atinc and Walton (1998) noted that during the Asian financial crisis, countries such as South Korea, Indonesia, Thailand, and Malaysia executed SPP to thwart and alleviate severe economic failure and deprivation. In this context, ILO (2020) and Hallegatte and Hammer (2020) mentioned that the SPP are executed new social protection schemes to support the poor and vulnerable groups during the COVID-19 pandemic. These SPP consisted of elders and health care assistance, unemployment protection, social security, and in-kind and cash transfers.

The current study will focus on the SPP which are implemented by the governments to assist the poor, vulnerable groups, and economic sectors to mitigate the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. Derived from the above consideration, the SPP include all public policy initiatives to combat hunger, reduce poverty and social inequality, and stabilize the economy. Consequently, the study aims to explore the current implementation of SPP in COVID-19, particularly in the most affected countries. It also provides learned lessons for countries that had not previously considered implementing SPP up until the COVID-19 crisis.

Social Protection: Concepts and Programs

Early by the 1990s, the SPP have been executed by many countries to cope with the economic crisis. Recently, the European Consensus included the SPP in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development due to their vital role in combating hunger, reducing poverty, and social inequality (UN 2015).

Despite the global increase of SPP, there is no specific definition of what social protection stands for but the International Labor Organization (ILO) mentioned in 102 conventions that social protection is considered as “social security”. Besides, Guhan (1994) highlighted that ILO definition of social protection can only be accepted for the case of developing countries. Consequently, Brand (2001) mentioned that in LDCs, social security is a component of integrated anti-poverty policies. These policies include providing productive resources, and ensuring employment, minimum wage, and food security to the poor and vulnerable groups.

The SPP refer to providing income through medical care assistance, sickness benefits, unemployment, family, and maternity assistances. This means that SPP consist of both private and public measures targeting to assist the poor and vulnerable groups and therefore to reduce their exposure to economic and social vulnerability (Brand 2001; Devereux and Sabates-Wheeler 2004). Accordingly, Niño-Zarazúa et al. (2012) and Fiszbein et al. (2013) clarified that SPP are performed to tackle the causes of poverty and its indicators, especially in developing countries.

Furthermore, Niño-Zarazúa et al. (2012) and Fiszbein et al. (2014) noted that the social protection has three main functions: protecting the basic levels of consumption, facilitating human investment, and assisting the poor to overcome some difficulties. In this context, Fiszbein et al. (2014) emphasized that the key role of social protection in the agenda post-2015 is “an instrument for the goals of reducing poverty, reducing inequality, reducing risk and vulnerability”. Therefore, the social protection includes three main components: social insurance, labor market intervention, and social assistance programs.

The World Bank Atlas of Social Protection Indicator of Resilience and Equity (ASPIRE) is the most acknowledged classification of social protection and consisted of social insurance, labor market, social assistance, and private transfers (Table 1).

Worldwide, the SPP have rapidly increased; Lowder et al. (2017) noted that during the two past decades, about 2.1 billion people are beneficiaries of the SPP in developing countries. In addition, Fiszbein et al. (2014) emphasized that over the world, about 24% of the extremely poor are beneficiaries of the social assistance programs, 3% of the population benefit from social insurance, and 3% of the population are the recipient of the labor market.

The types and the coverage of SPP vary from one region to another. In this context, Devereux (2002) and Dev et al. (2007) mentioned that the schemes of social protection, the SPP funding, the targeting approaches, the monitoring systems, and the size of the programs depend on the political objectives. According to the World Bank (2020), worldwide, about 74.3% of the population in high-income countries, 64.2% of the population in upper-middle-income countries, 31.1% of the population in lower-middle-income countries, and 19.1% of the population in low-income countries are covered by SPP. However, about 80.9% of the population in low-income countries are not covered by SPP (Fig. 1).

Social protection and labor coverage (World Bank 2020)

SPP as a Response to Pandemic Crises

Recently, many countries challenged various crises either natural disasters or human-made crises. In fact, crisis and crisis management become key concepts and many authors highlight the essential of these concepts in critical decisions.

Accordingly, Santana (2004) mentioned that the term “crisis” is so complicated to define due to several reasons; its construct, it is overlapping with other terms such as catastrophe and disaster, and its different application and use. For Faulkner (2001) and Prideaux et al. (2003), the crisis refers to an unpredictable and self-made situation due to various causes that commonly lead to catastrophic changes difficult to handle. For instance, previously, Sönmez et al. (1999) mentioned that the crises include political instability, terrorism, conflicts, wars, natural disasters, public health threats, and so on.

Tamer (2004) stated that due to the rising occurrence of various disasters, crisis management becomes a significant topic for policymakers in many countries. Indeed, there are several approaches to manage crises. Moe and Pathranarakul (2006) highlighted that proactive approach is widely applied by policymakers in managing the crises. This approach includes mitigations, preparedness, and warnings and aims at reducing social disorders during the crises. Additionally, Solt (2018) emphasized that mitigation strategies are executed by the governments, organizations, and institutions and they include the implementation of new legal regulations, creating new programs, initiatives, or committees to reduce the adverse impacts of the crisis.

Compared with previous pandemic crises such as Ebola, AIDS, and SARS that occurred in Sierra Leone, Liberia, South Africa, and Malawi, the COVID-19 pandemic is a global threat. Accordingly, worldwide, the pandemic affects diversely the countries and led to various negative impacts such as macroeconomic crises, bankruptcies, the increase of social inequality, and poverty (Furman 2020; Odendahl and Springford 2020; Gali 2020). This risks to affect the countries’ economy and worsen the living conditions. McInnes (2016) and Tandon and Hasan (2005) asserted that the pandemics mostly affected the poor and vulnerable groups with limited resources which cannot allow them to overcome the adverse consequences of the crisis. In this context, many countries focused on implementing various crisis management strategies and measures to cope with the negative impact of COVID-19.

According to Fink (1986), crisis management refers to a comprehensive process, which includes strategies reducing the occurrence and the impacts of the crises. Furthermore, Tamer (2004) highlighted that crisis management involves all private and/ public interventions. It is an important topic for policymakers regarding the increasing occurrence of various disasters. Many authors stated that pandemics are a great challenge for policymakers. Crisis management strategies and policies are one of the most key tools to deal with the negative socioeconomic impacts. In this context, the social protection becomes a vital policy which contains various types of programs targeting to prevent, mitigate, and cope with the impacts of the crisis (Holzmann and Jørgensen 2001; Hooghe and Marks 2003; Rutkowski and Bousquet 2019).

Previously, SPP have been implemented during pandemic crises (see Table 2). In fact, the first cases of Ebola were registered in Sierra Leone by September 30, 2014. Then, the pandemic spread to neighbouring country such as Liberia. By December 2014, Sierra Leone and Liberia counted about 11,751 infected cases and 3691 deaths (Shin et al. 2018; Meltzer et al. 2014).

Accordingly, many NGOs and some international organizations supported the governments to breakout the Ebola pandemic. For instance, UNICEF implemented infant feeding programs which targeted to improve the quality of primary health care, building units to isolate infected people, delivering medical supplies, and increasing communities’ awareness (Acosta et al. 2011; WHO 2015; Hewlett and Hewlett 2007; Shiwaku et al. 2007; Hick et al. 2010; Shin et al. 2018).

Likewise, in Malawi and South Africa, SPP especially cash transfer programs have been realized to deal with HIV prevalence. These programs were delivered under conditional assistance to girls aged between 15 and 24 years old to enhance their school attendance and increase their awareness about sexual culture (Baird et al. 2012; Pettifor et al. 2016). For instance, in Malawi, cash transfers were provided for 18 months to support families to mitigate with deprivation and poverty risks. This cash transfer has been implemented through collaborations between various actors such government, non-governmental organization, civil society, and international organizations (Baird et al. 2012; Pfeiffer 2003; Barrientos 2016).

Table 2 shows that SPP have been executed during some previous pandemic crises such as Ebola, AIDs, and HIV. These pandemics occurred in low-income countries and most of the executed SPP focused mainly on in-kind and cash transfers. Additionally, these programs are targeted to the poor and vulnerable groups (Ebola survivors, pregnant or lactating women, malnourished children) to support them to overcome the impacts of the crises. It can be noticed that the above-mentioned pandemic crises occurred in low-income countries where most of people live under poverty line.

On the other hand, COVID-19 is the current pandemic crisis. It differs from the previous ones according to its worldwide spreading and its negative impacts on the economy. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic affected mostly the high-income countries and upper-middle income countries. Consequently, many countries executed several measures to breakout the COVID-19 pandemic. One of the most important measures is the implementation of SPP. Gentilini et al. (2020c) highlighted that over the world, around 195 countries implemented various SPP such as safety net, finance, social insurance, and labor market to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, 131 countries implemented about 271 cash transfers programs by June 2020, 125 countries executed about 63 social insurance programs, and 85 countries implemented approximately 140 labor market programs.

Methodology

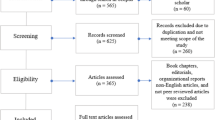

In this study, the systematic review has been used. It consists of summarizing and assessing the state of knowledge related to a given research question structured to existing knowledge. According to Ford and Pearce, (2010) systematic review differs from the traditional literature review. Firstly, it focuses on clear questions; secondly, the approach specifies systematic, clear reformulation, and criteria to select relevant research. Therefore, it includes the full reporting of search terms and the criteria for inclusion and exclusion of articles. The current study is based on data collected from English peer-reviewed scientific literature documenting the SPP concept, implementation and types of SPP in the COVID-19 pandemic in the most affected countries. Relevant articles published and current information related to the COVID-19 pandemic from WOS, Google Scholar databases, ILO, World Bank reports and Aljazeera Television have been selected according to well-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria as shown in Table 3.

To access to the primary literature related to SPP executed in managing the COVID-19 pandemic, search terms (social protection, social protection programs, COVID-19 pandemic, social assistance, pandemic crises, social insurance, cash & in-kind transfers, vulnerable groups, mitigation, pandemic crisis, COVID-19 breakout/coping strategy, crisis management, middle and high-income countries) have been used through WOS, Google scholar, ILO, World Bank, and WHO web sites. A total of 250 relevant publications were selected from the initial screen but after importing into Endnote 180, articles were retained. A visual check of the titles was conducted to remove 80 articles. The abstract of 100 articles have been read according to the inclusion criteria from which 80 was retained for full review. Finally, a total of 62 relevant papers (articles, official reports) have been retained for the full review.

Results and Discussion

Results

According to the main components of SPP (types of programs, targeting beneficiaries, and delivered social grants), the authors designed Table 4 to give an overview about the implementation of these programs in the most affected countries.

Discussion

Table 4 shows that many countries implemented SPP to provide financial support to the poor, vulnerable groups, and economic sectors, which are impacted directly/indirectly by the COVID-19 pandemic. These programs include employment protection measures, cash and in-kind transfers, social insurance to the poor, vulnerable groups, firms, and companies to enhance their resilience to cope with the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. From Table 4, it can be noticed that most of the countries executed assistance programs, especially in-kind and cash transfers. This could be due to the easy implementation of these types of SPP and their ability to enhance people’s resilience to cope with the direct consequences of COVID-19. These programs could also increase the livelihoods of the targeted beneficiaries and reinforce their ability to respect the restricted measures such as lockdown and curfews implemented by the countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Similarly, Braun and Ikeda (2020) mentioned that the cash transfer programs are implemented to alleviate consumption inequality, deliver assets, and enhance the capacity of the poor and vulnerable groups.

On the other hand, in this study, almost the high-income countries implemented labor market programs such as grants to support the firms and businesses. This could help them to overcome the increasing unemployment rate due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Hence, these programs are implemented to support the small- and middle-size enterprises and informal employees who can be easily affected by the pandemic. These results are consistent with ILO (2009), and Asenjo and Pignatti (2019) who reported that unemployment protection programs are temporary policies which target to decrease the unemployment rate during the crisis. In addition, Fort et al. (2013) clarified that limited financial and managerial resources make SMEs and informal employees more vulnerable to exogenous shocks.

With regard to the type of beneficiaries, both high-income and upper middle-income countries executed social insurance programs targeting to elderly, people with severe disabilities, employees staying at home without any remote work, people infected by COVID-19, workers without social insurance, and migrants. These programs could help those beneficiaries to overcome the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Likewise, Sumberg and Sabates-Wheeler (2011) highlighted that SPP prevent and protect vulnerable groups against various shocks.

The study showed that public SPP become key tools in managing the COVID-19 pandemic. Accordingly, high-income, middle-income, and low-middle income countries implemented SPP as an economic stimulus to respond to short-, middle-, and long-term negative consequences of the crisis.

Learned Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic

-

The study showed that despite the difference of the countries socioeconomic features, SPP have become a strategic tool in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. Accordingly, most of high-income countries (Spain, Italy Germany, UK, Chile) focus mostly on implementing SPP to stabilize the macroeconomic impacts of the pandemic while upper-middle and lower-middle-income countries (Turkey, Peru, Brazil, India, Pakistan) focused on executing the SPP to enhance the living conditions of the poor and vulnerable groups during the pandemic crisis.

-

From previous implementation of SPP during pandemic crises such as Ebola, AIDS, and HIV, the NGOs and international institutions played an important role, while most of SPP during the COVID-19 pandemic have been implemented by governments

-

The COVID-19 pandemic led to an extension of the implementation of SPP, increasing of SPP coverage, and a creation of new programs. Then, countries applied multipurpose strategy (various types of employees in informal sectors, enterprises and firms, increasing pre-existing amounts of social assistance, and new delivery mechanisms (E-transfers) to overcome several impacts of the pandemic.

-

During the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, the SPP become more technology-dependent (emergency of E-cash transfer and helpline in kind-assistance) such as Turkey

-

SPP can be used as tool to increase community resilience towards imposed restrictions during the crisis.

-

Besides, some countries carried out new SPP such as migrants such as China.

-

The breakout to the COVID-19 pandemic showed the fragility of European Union which was up to now considered to have the most developed health system and well-organized common policy scheme.

Conclusion and Recommendations

This study explores the current implementation of SPP in COVID-19, particularly in the most affected countries. It showed that social protection becomes a key policy tool, especially in high-income countries where SPP are executed for multi-purposes. Therefore, SPP are flexible and adoptable tools that the policymakers could use to enhance community resilience for various future shocks such as pandemic crises.

Accordingly, the findings of this study are essential to inform the policymakers in the countries with lack of proper SPP to include such programs in their social protection schemes for better management of various crises in the future. Then, in low-income countries, the policymakers could, for instance, formalize the SPP applied by NGOs or include them in the public social protection scheme. This could help the countries to assist efficiently the vulnerable groups during various future crises.

It can be seen that within some economic and political organizations such as the European Union and the African Union, there is a lack of comprehensive strategies in implementing the SPP to overcome the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, there is an urgent need for these organizations to plan common social protection policy for better management of crises in the future.

References

Acosta, J. D., Chandra, A., Sleeper, S., & Springgate, B. (2011). The nongovernmental sector in disaster resilience: conference recommendations for a policy agenda. Rand Corporation.

Alderman, H., & Yemtsov, R. (2012). Productive role of safety nets: background paper for the World Bank 2012-2022 social protection and labor strategy (no. 67609). The World Bank.

Andrews, C., Hsiao, A., & Ralston, L. (2018). Social safety nets promote poverty reduction, increase resilience, and expand opportunities.

Asenjo, A., & Pignatti, C. (2019). Unemployment insurance schemes around the world evidence and policy options (no. 995045193402676). International Labour Organization.

Atinc, T. M., & Walton, M. (1998). Social consequences of the East Asian financial crisis. World Bank Group.

Baird, S. J., Garfein, R. S., McIntosh, C. T., & Özler, B. (2012). Effect of a cash transfer programme for schooling on prevalence of HIV and herpes simplex type 2 in Malawi: a cluster randomised trial. The Lancet, 379(9823), 1320–1329.

Barrientos, A. (2016). From evidence to action: the story of cash transfers and impact evaluation in Sub-Saharan Africa, edited by Benjamin Davis, Sudhanshu Handa, Nicola Hypher, Nicola Winder, Paul C. Winters, and Jennifer Yablonski. Journal of Development Studies, 52(12), 1831–1832.

Beegle, K., Honorati, M., & Monsalve, E. (2018). Reaching the poor and vulnerable in Africa through social safety nets.

Brand, H. (2001). World Labour Report 2000: income security and social protection in a changing world. Monthly Labor Review, 124(6), 47–47.

Braun, R. A., & Ikeda, D. (2020). Why cash transfers are good policy in the COVID-19 pandemic (no. 2020–4). Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

Cash Learning Partnership. (2017). Glossary of cash transfer programming (CTP) terminology. Oxford: Cash Learning Partnership (CaLP).

Dev, S. M., Subbarao, K., Galab, S., & Ravi, C. (2007). Safety net programmes: outreach and effectiveness. Economic and Political Weekly, 3555–3565.

Devereux, S. (2002). Can social safety nets reduce chronic poverty? Development Policy Review, 20(5), 657–675.

Devereux, S., & Sabates-Wheeler, R. (2004). Transformative social protection.

Faulkner, B. (2001). Towards a framework for tourism disaster management. Tourism Management, 22(2), 135–147.

Fink, S., & American Management Association. (1986). Crisis management: planning for the inevitable. Amacom.

Fiszbein, A., Kanbur, R., & Yemtsov, R. (2013). Social protection, poverty and the post-2015 agenda. The World Bank.

Fiszbein, A., Kanbur, R., & Yemtsov, R. (2014). Social protection and poverty reduction: global patterns and some targets. World Development, 61, 167–177.

Ford, J. D., & Pearce, T. (2010). What we know, do not know, and need to know about climate change vulnerability in the western Canadian Arctic: a systematic literature review. Environmental Research Letters, 5(1), 014008.

Fort, T. C., Haltiwanger, J., Jarmin, R. S., & Miranda, J. (2013). How firms respond to business cycles: the role of firm age and firm size. IMF Economic Review, 61(3), 520–559.

Furman, J. (2020) 21 Protecting people now, helping the economy rebound later. Mitigating the COVID Economic Crisis: Act Fast and Do Whatever, 191.

Gali, J (2020), “The effects of a money-financed fiscal stimulus”, Journal of Monetary Economics, forthcoming.

Gentilini, U., Almenfi, M. Orton, I. & Dale, P. (2020a). Social protection and jobs responses to COVID-19: a real-time review of country measures, “Living paper” version 3, Available at: http://www.ugogentilini.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Country-social-protection-COVID-responses_April3-1.pdf (Accessed on 09 Apr 2020).

Gentilini., Almenfi, M. Orton, I. & Dale, P. (2020b). Social protection and jobs responses to COVID-19: a real-time review of country measures “Living paper” version 4, Available at: http://www.ugogentilini.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Country-SP-COVID-responses_April10.pdf (Accessed on 12 Apr 2020).

Gentilini, U., Almenfi, M., Orton, I., & Dale, P. (2020c). Social protection and jobs responses to COVID-19.

Guhan, S. (1994). Social security options for developing countries. Int'l Lab. Rev., 133, 35.

Hallegatte, S., & Hammer, S. (2020). Thinking Ahead: For a Sustainable Recovery from COVID-19. World Bank Blogs. Available at: https://blogs.worldbank.org/climatechange/thinking-aheadsustainable-recovery-covid-19-coronavirus. Accessed on 10 Apr 2020.).

Handa, S., Natali, L., Seidenfeld, D., Tembo, G., Davis, B., & Zambia Cash Transfer Evaluation Study Team. (2018). Can unconditional cash transfers raise long-term living standards? Evidence from Zambia. Journal of Development Economics, 133, 42–65.

Hewlett, B. S., & Hewlett, B. L. (2007). Ebola, culture and politics: the anthropology of an emerging disease. Cengage Learning.

Hick, J. L., Christian, M. D., & Sprung, C. L. (2010). Surge capacity and infrastructure considerations for mass critical care. Intensive Care Medicine, 36(1), 11–20.

Hidrobo, M., Hoddinott, J., Kumar, N., & Olivier, M. (2018). Social protection, food security, and asset formation. World Development, 101, 88–103.

Holzmann, R., & Jørgensen, S. (2001). Social risk management: a new conceptual framework for social protection, and beyond. International Tax and Public Finance, 8(4), 529–556.

Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2003). Unraveling the central state, but how? Types of multi-level governance. American Political Science Review, 233–243.

ILO (2009). Protecting people, promoting jobs: a survey of country employment and social protection policy responses to the global economic crisis, report to the G20 Leaders’ Summit, Pittsburgh, 24–25September.

ILO (2020). Social protection responses to the Covid-19 crisis Country responses in Asia and the Pacific. Available at https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/asia/worldbangkok/documents/briefingnote/wcms_739587.pdf. (Accessed on 30 Mar 2020).

Lowder, S. K., Bertini, R., & Croppenstedt, A. (2017). Poverty, social protection and agriculture: levels and trends in data. Global Food Security, 15, 94–107.

Mayberry, K., Siddiqui, U. & Najjar, F (2020). Global coronavirus cases exceed two million: live updates, Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/04/trump-cuts-funding-coronavirus-pandemic-live-updates-200414231400449.html (Accessed on 17 Apr 2020).

McInnes, C. (2016). Crisis! What crisis? Global health and the 2014–15 West African Ebola outbreak. Third World Quarterly, 37(3), 380–400.

Meltzer, M. I., Atkins, C. Y., Santibanez, S., Knust, B., Petersen, B. W., Ervin, E. D., & Washington, M. L. (2014). Estimating the future number of cases in the Ebola epidemic--Liberia and Sierra Leone, 2014–2015.

Moe, T. L., & Pathranarakul, P. (2006). An integrated approach to natural disaster management. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal.

Niño-Zarazúa, M., Barrientos, A., Hickey, S., & Hulme, D. (2012). Social protection in Sub-Saharan Africa: getting the politics right. World Development, 40(1), 163–176.

Odendahl, C., & Springford, J. (2020). Bold policies needed to counter the coronavirus recession. Mitigating the COVID Economic Crisis: Act Fast and Do Whatever It Takes, 145–150.

Pettifor, A., MacPhail, C., Hughes, J. P., Selin, A., Wang, J., Gómez-Olivé, F. X., & Suchindran, C. (2016). The effect of a conditional cash transfer on HIV incidence in young women in rural South Africa (HPTN 068): a phase 3, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Global Health, 4(12), e978–e988.

Pfeiffer, J. (2003). International NGOs and primary health care in Mozambique: the need for a new model of collaboration. Social Science & Medicine, 56(4), 725–738.

Prideaux, B., Laws, E., & Faulkner, B. (2003). Events in Indonesia: exploring the limits to formal tourism trends forecasting methods in complex crisis situations. Tourism Management, 24(4), 475–487.

Richardson, E. T., Kelly, J. D., Sesay, O., Drasher, M. D., Desai, I. K., Frankfurter, R., & Barrie, M. B. (2017). The symbolic violence of ‘outbreak’: a mixed-methods, quasi-experimental impact evaluation of social protection on Ebola survivor wellbeing. Social Science & Medicine, 195, 77–82.

Rutkowski, M. & Bousquet, F. (2019). Social protection: protecting the poor and vulnerable during crises. Available at https://blogs.worldbank.org/dev4peace/social-protection-protecting-poor-and-vulnerable-during-crises. Accessed on 10 Apr 2020.

Sabin, L., Tsoka, M., Brooks, M. I., & Miller, C. (2011). Measuring vulnerability among orphans and vulnerable children in rural Malawi: validation study of the Child Status Index tool. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 58(1), e1–e10.

Santana, G. (2004). Crisis management and tourism: beyond the rhetoric. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 15(4), 299–321.

Shin, Y. A., Yeo, J., & Jung, K. (2018). The effectiveness of international non-governmental organizations’ response operations during public health emergency: lessons learned from the 2014 Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(4), 650.

Shiwaku, K., Shaw, R., Kandel, R. C., Shrestha, S. N., & Dixit, A. M. (2007). Future perspective of school disaster education in Nepal. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal.

Solt, E. (2018). Managing international financial crises: responses, lessons and prevention. Crisis Management: Theory and Practice, 135.

Sönmez, S. F., Apostolopoulos, Y., & Tarlow, P. (1999). Tourism in crisis: managing the effects of terrorism. Journal of Travel Research, 38(1), 13–18.

Sumberg, J., & Sabates-Wheeler, R. (2011). Linking agricultural development to school feeding in sub-Saharan Africa: theoretical perspectives. Food Policy, 36(3), 341–349.

Tamer, M. (2004). Türkiye’de ve Polis Teşkilatında Kriz Yönetimi Yapısının Terör Açısından Değerlendirilmesi. Polis Dergisi, 40, 281–289.

Tandon, A., & Hasan, R. (2005). Highlighting poverty as vulnerability: the 2005 earthquake in Pakistan.

United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. New York: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

WHO (2020). https://covid19.who.int/. Acceded at 27 July 2020.

World Bank. (2019). ASPIRE: The Atlas of Social Protection: Indicators of Resilience and Equity.

World Bank. (2020). https://www.worldbank.org/en/data/datatopics/aspire#1. Accessed 15 April 2020.

World Health Organization. (2015). WHO: Ebola situation report 16 September 2015.

Wu, J. T., Leung, K., & Leung, G. M. (2020). Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. The Lancet, 395(10225), 689–697.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants and animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abdoul-Azize, H.T., El Gamil, R. Social Protection as a Key Tool in Crisis Management: Learnt Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic. Glob Soc Welf 8, 107–116 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40609-020-00190-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40609-020-00190-4