Abstract

We compare different implementations of the Stochastic Becker–DeGroot–Marschak (SBDM) belief elicitation mechanism, which is theoretically elegant but challenging to implement. In a first experiment, we compare three common formats of the mechanism in terms of speed and data quality. We find that all formats yield reports with similar levels of accuracy and precision, but that the instructions and reporting format adapted from Hao and Houser (J Risk Uncertain 44(2):161–180 2012) is significantly faster to implement. We use this format in a second experiment in which we vary the delivery method and quiz procedure. Dropping the pre-experiment quiz significantly compromises the accuracy of subject’s reports and leads to a dramatic spike in boundary reports. However, switching between electronic and paper-based instructions and quizzes does not affect the accuracy or precision of subjects’ reports.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The term “probabilistic sophistication” is used as per Machina and Schmeidler (1992)—that is, that the subject ranks lotteries based purely on the implied probability distribution over outcomes. The practical implication is that a subject will rank bets with subjective probabilities over outcomes in the same manner as he would rank lotteries with an objective probability distribution. Epstein (1999) defines ambiguity neutrality as a decision-maker for which the probability is sophisticated. Thus, SBDM is not in general incentive compatible when decision-makers are ambiguity averse. “Dominance” is the condition that a subject has preference relation \(\succeq\) over lotteries such that \(H_\text {p}L \succeq H_{\text {p}'}L\) for all \(H > L\) if and only if \(p\ge p'\).

Ducharme and Donnell (1973) present the first experimental test of the mechanism and observe that while it is “basically simple”, the SBDM mechanism task “seems complicated at first exposure”.

By restricting subjects to a single switch point we might prevent subjects from reporting their true preferences and/or imposing consistency when subjects are actually confused. However, as we did not allow for multiple reports in the other two mechanisms the cleanest comparison is to preserve a single switch point.

Subjects’ total completion time for Experiment 1 varied between 16 and 58 min, and subjects received an average payoff of $25.95.

Typically precision is defined as the inverse of the variance. However, since some subjects have zero variance, this measure is unbounded.

As in Holt and Smith (2016), the difference in boundary reports is significant in a randomisation test at the 0.01 level. We note, however, that the proportion of these reports is much smaller in our sample than in theirs. This is due in part to restricting our Bayesian task to a single draw.

Note that every screen in the TK format reminds subjects of the color of the ball they have observed. Thus, the reverse reporting is unlikely to be due to recall and is more likely due to distraction or a lack of salience.

The Q treatment is identical to the HH treatment and was repeated to allow for within-session randomization. Completion times in the Q treatment were slightly faster than the HH treatment with a mean session time of 766 s and a median session time of 695 s. However, the difference in session times is not significant using a Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon test (p value \(= 0.13\)).

Times for all treatments are measured precisely, with the exception of the paper treatment. When running the paper treatment, the laboratory assistant noted the times at which instructions were distributed, the time at which instructions were swapped for the quiz, and the time when the subject completed the quiz successfully. These times were noted in minutes rather than seconds, with all time-based analysis using the mid-point of the minute in question. There was 1 lab assistant and 15 subjects in each P treatment.

All randomisation test results are included in the Appendix.

References

Becker, G. M., DeGroot, M. H., & Marschak, J. (1964). Measuring utility by a single-response sequential method. Behavioral Science, 9(3), 226–232.

Ducharme, W. M., & Donnell, M. L. (1973). Intrasubject comparison of four response modes for “subjective probability” assessment. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 10(1), 108–117.

Epstein, L. (1999). A definition of uncertainty aversion. The Review of Economic Studies, 66(3), 579–609.

Grether, D. M. (1992). Testing bayes rule and the representativeness heuristic: Some experimental evidence. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 17(1), 31–57.

Hao, L., & Houser, D. (2012). Belief elicitation in the presence of naïve respondents: An experimental study. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 44(2), 161–180.

Harrison, G. W., & Rutström, E. E. (2009). Expected utility theory and prospect theory: One wedding and a decent funeral. Experimental Economics, 12(2), 133–158.

Hollard, G., Massoni, S., & Vergnaud, J.-C. (2016). In search of good probability assessors: An experimental comparison of elicitation rules for confidence judgments. Theory and Decision, 80(3), 363–387.

Holt, C. A., & Laury, S. K. (2002). Risk aversion and incentive effects. American Economic Review, 92(5), 1644–1655.

Holt, C. A., & Smith, A. M. (2009). An update on bayesian updating. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 69(2), 125–134.

Holt, C. A., & Smith, A. M. (2016). Belief elicitation with a synchronized lottery choice menu that is invariant to risk attitudes. American Economic Journal Microeconomics, 8(1), 110–39.

Huck, S., & Weizsäcker, G. (2002). Do players correctly estimate what others do? Evidence of conservatism in beliefs. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 47, 71–85.

Karni, E. (2009). A theory of medical decision making under uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 39(1), 1–16.

Machina, M. J., & Schmeidler, D. (1992). A more robust definition of subjective probability. Econometrica, 60(4), 745–780.

Massoni, S., Gajdos, T., & Vergnaud, J.-C. (2014). Confidence measurement in the light of signal detection theory. Frontiers in Psychology, 1455(5), 1–13.

Möbius, M. M., Niederle, M., Niehaus, P., & Rosenblat, T. (2007). Gender differences in incorporating performance feedback. draft, February.

Möbius, M. M., Niederle, M., Niehaus, P., & Rosenblat, T. S. (2011). Managing self-confidence: Theory and experimental evidence. Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Palfrey, T., & Wang, S. (2009). On eliciting beliefs in strategic games. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 71, 98–109.

Schlag, K. H., Tremewan, J., & Van der Weele, J. J. (2013). A penny for your thoughts: A survey of methods for eliciting beliefs. Experimental Economics, 18(3), 1–34.

Schotter, A., & Trevino, I. (2014). Belief elicitation in the laboratory. Annual Review of Economics, 6(1), 103–128.

Trautmann, S. T., & van de Kuilen, G. (2015). Belief elicitation: A horse race among truth serums. The Economic Journal, 125, 2116–2135.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We thank Amy Corman, Laboratory Manager at the University of Melbourne’s Experimental Economics Lab. We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Australian Research Council through the Discovery Early Career Research Award DE140101014 as well as the Faculty of Business and Economics at the University of Melbourne.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix A: Randomisation test results

Appendix A: Randomisation test results

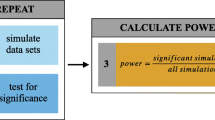

Table 7 reports the results of pairwise randomization tests which compare outcomes from treatments in Experiments 1 and 2. All randomization tests are based on 500,000 simulations for comparability with the randomization test results reported in Holt and Smith (2016).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Burfurd, I., Wilkening, T. Experimental guidance for eliciting beliefs with the Stochastic Becker–DeGroot–Marschak mechanism. J Econ Sci Assoc 4, 15–28 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40881-018-0046-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40881-018-0046-5