Abstract

Background

Omalizumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody indicated as add-on therapy to improve asthma control in patients with severe persistent allergic asthma.

Aims

The aim of this study was to evaluate social, healthcare expenditure and clinical outcomes changes after incorporating omalizumab into standard treatment in the control of severe asthma.

Methods

In this multicentre retrospective study, a total of 220 patients were included from 15 respiratory medicine departments in the regions of Andalusia and Extremadura (Spain). Effectiveness was calculated as a 3-point increase in the Asthma Control Test (ACT) and a reduction in the annual number of exacerbations. The economic evaluation included both direct and indirect costs. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was calculated. Results from the year before and the year after incorporation of omalizumab were compared.

Results

After adding omalizumab, improvement of lung function, asthma and rhinitis according to patient perception, as well as the number of exacerbations and asthma control measured by the ACT score were observed. Globally, both healthcare resources and pharmacological costs decreased after omalizumab treatment, excluding omalizumab cost. When only direct costs were considered, the ICER was €1712 (95% CI 1487–1995) per avoided exacerbation and €3859 (95% CI 3327–4418) for every 3-point increase in the ACT score. When both direct and indirect costs were considered, the ICER was €1607 (95% CI 1385–1885) for every avoided exacerbation and €3555 (95% CI 3012–4125) for every 3-point increase.

Conclusions

Omalizumab was shown to be an effective add-on therapy for patients with persistent severe asthma and allowed reducing key drivers of asthma-related costs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Omalizumab may be an effective add-on therapy for patients with persistent severe asthma. |

The use of omalizumab reduces key drivers of asthma-related costs, including acute exacerbation episodes, visits to the emergency department, and the need for in-patient care, all of which account for the cost effectiveness of this biologic treatment. |

1 Introduction

Allergic asthma is a long-term disorder of the airways resulting from overexpression of immunoglobulin E (IgE) in response to environmental allergens. Symptoms can be controlled by limiting environmental exposures that may aggravate the patient’s asthma or by using medications such as inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) to reduce the inflammation associated with the disease. However, despite guideline-based treatment, there is a population of asthmatics who continue to have poor asthma control and experience acute exacerbations, requiring additional treatment including hospitalizations [1, 2]. Severe exacerbations are potentially life-threatening. Patients with poorly controlled asthma often require oral corticosteroids to control their disease [3]. Oral corticosteroids are associated with a number of side effects, including osteoporosis, cataracts, and, potentially, Cushing’s syndrome [4]. Moreover, the prevalence of allergic diseases and asthma are increasing worldwide, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, representing a major global challenge that threatens health and economies alike [5, 6].

Omalizumab is a biologic humanized anti-IgE antibody that prevents binding of circulating IgE to the receptor, thereby inhibiting the allergic–inflammatory cascade. Omalizumab provides a non-steroidal treatment option for patients with moderate to severe persistent allergic asthma, whose symptoms are inadequately controlled with high-dose ICS. Omalizumab add-on therapy has been shown to reduce the number of asthma exacerbations and improve symptom severity and quality of life [7]. Omalizumab is currently recommended in asthma guidelines, as part of treatment algorithms [8,9,10].

Improvements in clinical outcomes may be plausibly associated with reductions in the economic burden of asthma. Studies carried out in different healthcare settings have provided evidence of the advantages of omalizumab add-on therapy in terms of cost effectiveness in the management of patients with severe asthma [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Two systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) contributing a total of 1071 and 2037 patients with allergic asthma and high levels of IgE, respectively [19, 20], showed significant decreases in daily corticosteroid usage and effective reduction of asthma exacerbations, emergency room visits, and asthma hospitalizations, which in turn is the main driver of asthma-related healthcare costs. A recent systematic review of the literature has identified all available health economic evidence of omalizumab in the treatment of asthma and concludes that in patients with uncontrolled severe persistent allergic asthma, omalizumab therapy could be cost effective in a carefully selected subgroup of patients with the highest morbidity or the more severe forms of the disease [21].

Also, in a systematic review of the economic impact of biological asthma therapies, omalizumab was cost effective in case-based scenarios of most studies [22].

However, information on pharmacoeconomic studies carried out in patients with severe asthma treated with omalizumab in daily practice conditions is relatively scarce in our setting. In Spain, only two cost-effectiveness studies of omalizumab in patients with severe persistent asthma have been previously published [13, 14]. These studies included a small sample size reflecting the experience of patients seen in the respiratory medicine departments of two Spanish hospitals. In order to confirm previous findings, a further pharmacoeconomic analysis was conducted in a study population of 220 patients with severe asthma collected from 15 respiratory medicine departments in acute-care hospitals in the Autonomous Communities of Andalusia and Extremadura. The objective of the study was to assess changes in direct and indirect costs after 1 and 2 years, as well as improvements in clinical outcomes after 1 year of treatment with omalizumab for persistent severe asthma.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Design and Study Population

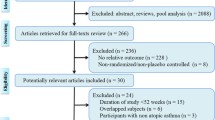

This retrospective chart review was performed in 15 hospital respiratory medicine departments in Andalusia and Extremadura in Spain. In order to select the eligible study population, a retrospective review of medical records was performed in all patients who met the eligibility criteria: aged 18 years or older, diagnosed with severe persistent asthma at least 12 months prior to the treatment with omalizumab, had started the treatment with omalizumab before 1 January 2014, and followed up in the respiratory medicine departments of the participating sites throughout the study observation period. Severe persistent allergic asthma was diagnosed according to GEMA (Guía Española para el Manejo del Asma) criteria [10]. To select patients for the study, we asked investigators to obtain a list of all eligible patients among their patients treated with omalizumab, sorted by medical record number; the first six patients, the last six patients and the middle four patients were selected.

The design (Fig. 1) and conduct of the study complied with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practices, and the study was approved by the Independent Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital of Jerez on 13 January 2015.

2.2 Patient Characteristics

Data were collected from medical records on age, gender, body mass index, smoking habits, lung function, asthma-associated diseases, Asthma Control Test (ACT) score, time since asthma diagnosis, eosinophil count and patients’ perception of asthma progression.

2.3 Outcomes

Two different measures of effectiveness were considered: (a) the avoidance of one asthma exacerbation, defined as an episode of worsening of the patient’s baseline situation requiring either a short (< 10 days) or a long (≥ 10 days) cycle of oral prednisone, a visit to the emergency department or hospital admission (when an admission was preceded by an emergency department visit, these were counted as one single exacerbation); or (b) a 3-point increase in ACT score [23].

2.4 Costs

Direct costs included healthcare resources and pharmacological costs. Hospital admissions due to exacerbations, recorded number of visits (emergency visits to primary care or the emergency department and non-scheduled visits), visits to nurses for the administration of omalizumab and prednisone cycles administered during exacerbations (excluding those started during admissions or emergency visits) were registered as healthcare resources. Pharmacological costs observed in this study included the medication for the management of severe persistent asthma, such as ICS, long-acting inhaled β2-agonist (LABA), leukotriene receptor antagonist, anticholinergics, theophylline, oral corticosteroids and omalizumab, as well as medications for the treatment of rhinitis. Indirect costs were calculated from the number of days of absence from work due to asthma (registered in the centre’s computer system) and daily salary according to gender and age of patients.

Resource unitary costs were obtained from the eSalud database [24]. Pharmacological costs were calculated according to unitary costs reported in the General Council of Official Pharmaceutical Colleges [25]. Pharmacological costs included those covered by the Spanish healthcare system and by patients. For pharmacological costs covered by the Spanish healthcare system, the Royal Decree on the tax-free retail price was used, according to the different pharmaceutical forms, as well as the Spanish healthcare system co-payment contribution, according to the number of employed and retired patients.

Indirect costs (disease impact on labour productivity) were calculated with the human capital method. Daily salary values were obtained from the Salary Structure Survey [26].

Costs were measured for the year prior to omalizumab prescription, for the first year after omalizumab prescription, and for the second year after omalizumab prescription, according to a societal perspective, including both direct and indirect costs. Direct healthcare costs and indirect costs were considered and expressed in 2016 euros.

2.5 Cost Effectiveness

The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was used to compare the impact of omalizumab in terms of costs and clinical outcomes. ICER was calculated as follows:

2.6 Sample Size

It was estimated that at least 239 patients were needed to detect a minimum difference of €1,000 in total costs (direct and indirect) between the pre- and post-omalizumab periods and assuming a common standard deviation of €5000 (alpha level of significance, 5%; power, 90%; unilateral paired contrast and replacement rate, 10%).

2.7 Statistical Analysis

Clinical data were described and compared within the different study observation periods. Data were described as absolute value (percentage), mean (standard deviation; SD) or median value (interquartile range), as appropriate.

We made two comparisons using McNemar or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, as appropriate: (i) periods before and after the introduction of omalizumab, and (ii) first-and second-year periods after the introduction of omalizumab. Two-tailed p values were reported and declared statistically significant when < 0.05. All analyses were performed using the R language (Core Team software, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2016. https://www.R-project.org/).

3 Results

3.1 Description of Study Population

A total of 239 patients were recruited, 220 (92.1%) of whom were included in the analysis of the first year as they had complete data for the main variables and so were considered evaluable, and 120 (50.2%) evaluable patients were included in the analysis of the second year. Mean age was 49.1 (SD 13.8) years and 71.8% of patients were female. Regarding clinical characteristics, mean time since diagnosis of asthma was 20.0 (13.4) years, and mean pre-bronchodilator FEV1 was 66.9% (20.9). The median baseline values for peripheral eosinophils in blood, IgE and fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) were 385 cells/µL, 571 IU/mL and 32 parts per billion (ppb), respectively. More clinical data are available in Table 1.

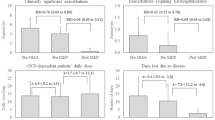

3.2 Effectiveness of Omalizumab

The mean number of exacerbations, calculated as prednisone cycles with or without a visit to the emergency department or hospitalization, was 7.6 (7.7) in the year prior to omalizumab prescription and 1.4 (2.9) after 1 year of omalizumab treatment (p < 0.001). The mean number of exacerbations, calculated as prednisone cycles without a visit to the emergency department or hospitalization, was also lower after omalizumab treatment. Mean ACT score was higher after 1 year of omalizumab treatment (11.5 [3.4] vs 19.9 [3.7]: p < 0.001) and the number of patients with uncontrolled asthma, according the ACT results, was − 76.3% lower (88.7% vs 12.4%; p < 0.001). Lung function improved +10.8 points after 1 year of treatment with omalizumab, as mean pre-bronchodilator FEV1 was 66.9% (20.9) in the previous year and 77.7% (21.6) after 1 year on omalizumab treatment (p < 0.001). Patients’ perception of disease progression was positive in > 92% of patients after omalizumab treatment, compared with only 6.4% in the previous year (p < 0.001). An improvement in rhinitis was also observed after omalizumab treatment, as 53.8% of patients reported better control compared with 3.7% in the previous period (p < 0.001). Mean eosinophil count fell from 387 (385) to 302 (280) cells/µL (p < 0.004) after 1 year on omalizumab treatment (Table 2).

3.3 Social, Healthcare and Pharmacological Resources

The number of short-term cycles of prednisone pre- and post-omalizumab decreased by 58.3% (p < 0.001), while the number of long-term cycles decreased by 80.7% (p < 0.001).

The mean number of hospital admissions per year during the pre-omalizumab period M (P25; Me; P75) was 0.38 (0.0; 0.0; 1.0), with a mean duration of 2.83 (0.0; 0.0; 3.0) days per admission, and 0.05 (0.0; 0.0; 0.0) in the first year (p < 0.001), with a mean duration of 0.32 (0.0; 0.0; 0.0) days per admission (p < 0.001). Non-scheduled visits to both primary care and the respiratory medicine department reduced in the first year of omalizumab treatment. When the first and second years of treatment with omalizumab were compared, no such differences in the use of healthcare resources were observed (Table 3).

The number of patients treated with ICS, leukotriene receptor antagonists, anticholinergics and oral corticosteroids (OCS) were significantly lower in the first year of omalizumab treatment than in the previous year. Similarly, the mean number of medications for the treatment of rhinitis needed by each patient also reduced. However, no significant differences were observed in the frequency of use of asthma medication between the first and the second year of treatment with omalizumab (Table 4).

The mean number of days of absence from work per patient was 19.60 (0.0; 5.0; 30.0) in the year prior to omalizumab prescription and 1.09 (0.0; 0.0; 0.0) in the first year of treatment (p < 0.001). No differences were observed in the number of days of absence from work during the first or second year of treatment with omalizumab.

3.4 Costs of Omalizumab

Asthma management costs related to healthcare resources only (i.e., excluding cost of medication) were €717 (321; 642; 645) per patient-year over the first year of treatment with omalizumab, and €1952 (260; 569; 2415) in the previous year (p < 0.001) (Table 5), signifying a €1235 difference (95% CI 1695–895).

Costs of pharmacological treatment for the management of asthma other than omalizumab were €1261 (1003; 1082; 1512) per patient-year in the pre-omalizumab period and €376 (263; 264; 488) in the first year post-omalizumab, with the difference between the two periods being −€884 (95% CI − 953 to − 820) (Table 6). The use of omalizumab represented a mean cost of €12,690 (8198; 9202; 16,400) per patient-year. Consequently, the difference in total costs of pharmacological treatment between pre- and post-omalizumab periods was +€11,799 (95% CI 10,886–12,787).

Indirect costs resulting from days of absence from work fell after omalizumab prescription from €697.9 (0.0; 0.0; 784.3) to €51.5 (0.0; 0.0; 0.0) (p < 0.001). Therefore, taking into account both direct and indirect costs, the mean cost of the pre-omalizumab period was €3911 (1468; 2485; 4847) and the post-omalizumab period was €13,890 (8712; 12,430; 17,520) (p < 0.001), a difference of €9979 (95% CI 8841–11,056).

No significant differences were found in costs of healthcare resources, pharmacological treatment or in indirect costs during the first and the second years of omalizumab treatment (data not shown).

3.5 Cost-Effectiveness of Omalizumab

ICER was assessed for the incorporation of omalizumab into patient treatment, resulting in €1712 (95% CI 1487–1995) per avoided exacerbation, in contrast with the pre-omalizumab period. When both direct and indirect costs were taken into account, the ICER was €1607 (95% CI 1385–1885) for every avoided exacerbation.

ICER resulted in €3859 (95% CI 3327–4418) for every clinically significant change in asthma control (3-point increase in the ACT) [23]. When indirect costs were included, the ICER was €3555 (95% CI 3012–4125) for every 3-point increase.

4 Discussion

This real-world study provides evidence of the effectiveness of omalizumab in the control of symptoms in patients with severe asthma, as shown by a significant reduction in exacerbations, non-scheduled medical consultations, visits to the emergency department, hospital admissions and duration of hospital stays as compared with 1-year data before the use of omalizumab. Benefits in clinical outcomes were also associated with reductions in the need for asthma medications, including remarkable decreases in the percentage of patients treated with ICS, leukotriene receptor antagonists, anticholinergic agents and, particularly, OCS. These clinically relevant findings obtained in daily practice conditions are consistent with results reported in previous studies regarding reduction of severe exacerbations [27–30], the need for systemic corticosteroids [31–33], the number of non-scheduled visits [27, 34, 35], emergency visits [33, 36] and hospital admissions [30, 33, 37], and the length of hospital stays [35, 38].

With regard to direct costs, we found a mean ICER of €1712/exacerbation avoided and €3858 for every 3-point increase in the ACT score. When both direct and indirect costs were considered, the mean ICER was €1607/exacerbation avoided and €3555 for every 3-point increase in the ACT score. In a study by Levy et al. [13], which included 47 patients with uncontrolled persistent asthma, the pre- and post-treatment analysis after the use of omalizumab for 10 months showed an ICER of €462.08/exacerbation avoided. Vennera et al. [14] used a time horizon of 12 months before and after initiation of treatment with omalizumab in 86 patients and reported an ICER of €1487.46/exacerbation avoided and €5425.13 per 3-point increase in ACT when direct costs were considered. When direct and indirect costs were estimated, ICERs were €1130.93/exacerbation avoided and €4124.79 per 3-point increase in ACT. These results are roughly in the range of those obtained in our study, although differences in the number of study patients and time horizons may account for the variation.

Comparisons with international studies are hampered by differences in healthcare systems and methods used for analysis. Using data from the real-life 1-year randomized open-label study (ETOPA) and Canada as a reference country, Brown et al. [39] found that base-case lifetime analysis for the first 5 years of treatment gave an ICER of €31,209 for standard therapy plus add-on omalizumab. Also, for a threshold value of €35,000, it was estimated that the probability of omalizumab being cost effective was 67.7%. In a Markov model comparing lifelong standard therapy (ST) with a treatment period of omalizumab add-on therapy based on efficacy data from the INNOVATE (Investigation of Omalizumab in Severe Asthma Treatment) trial (28 weeks, n = 419) and Swedish life table and cost data, Dewilde et al. [18] reported that omalizumab add-on therapy cost an additional €42,754 for 0.76 additional QALYs, resulting in an ICER of €56,091. This model assumed that patients are at risk of having an exacerbation every 2 weeks and are at risk of dying from a clinically significant severe asthma exacerbation.

Fewer exacerbations and an attractive cost-effectiveness ratio for omalizumab add-on therapy were also found by van Nooten et al. [12] in the Netherlands. In the year prior to omalizumab therapy, the per-person rate of exacerbations was 3.39 compared with 1.07 in the year in which omalizumab was administered. The discounted incremental lifetime additional costs for omalizumab were €55,865 for 1.46 additional QALYs, resulting in €38,371/QALY. In a 36-month study on the cost/utility of add-on omalizumab in persistent difficult-to-treat atopic asthma in Italy [40], a €450 increase in overall monthly costs was observed, but this cost increase translated into an incremental cost/utility ratio of €23,880 per QALY, which is quite a favourable and convenient figure in terms of the willingness to pay for health benefits in industrialized countries.

These results provide evidence of the cost effectiveness of omalizumab in terms of cost/QALY but we did not collect sufficient data from the EQ-5D questionnaire to perform a QALY analysis. In a review of 24 ‘real-life’ effectiveness studies of omalizumab in the treatment of severe allergic asthma that included 4117 patients from 32 countries, omalizumab therapy was associated with improvements across the full range of objective and subjective indicators [41]. Benefits of omalizumab may extend up to 2–4 years, and the majority of omalizumab-treated patients may benefit for many years in terms of clinical, quality of life and health resource utilization outcomes [41]. Interestingly, a recent study showed that omalizumab offers the same clinical benefit in patients with persistent allergic asthma regardless of whether the asthma was caused by seasonal or perennial allergens [42].

Limitations of the study include the retrospective design: our study design does not allow us to conclude causation; that is to say, we cannot attribute the observed pre-to-post changes to the addition of omalizumab. However, our study provides a clear picture of the changes observed after such an addition in the real world. On the other hand, our study sample was not probabilistic. Given that the number of patients per site is low, we preferred to ensure the inclusion of patients at different moments in time, in an attempt to reduce the impact of possible secular trends. Other limitations were the attrition bias related to the reduced number of patients followed up during the second year, and a probable over-representation of female patients, which may be explained by the socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of the geographic regions of Andalusia and Extremadura. These characteristics limit the generalization of our findings to other areas and healthcare settings. On the other hand, unobserved time trends could induce a bias in the effect estimate of omalizumab. Although the patient recruitment sorted by medical record number instead of start date of treatment could help to minimize this bias, known or unknown factors relating to the time of diagnosis or recruitment of patients could have influenced the observed effect of omalizumab.

In summary, the results of this study provide further real-world data on the effectiveness of omalizumab as add-on therapy in patients with persistent severe asthma. The use of omalizumab reduces key drivers of asthma-related costs, including acute exacerbation episodes, visits to the emergency department, and the need for in-patient care, all of which account for the cost effectiveness of this biologic treatment.

5 Conclusions

Omalizumab may be an effective add-on therapy for patients with persistent severe asthma. As the economic and social burden of severe persistent asthma is significant, it is important for clinicians and policy makers to consider studies that formally assess costs and health outcomes. This study addresses the cost effectiveness of omalizumab in two specific areas of Spain. Consequently, studies such as this are highly recommended in other regions of Spain and also at a national level.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to protecting participant confidentiality but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Lang DM. Severe asthma: epidemiology, burden of illness, and heterogeneity. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2015;36(6):418–24.

Sheehan WJ, Phipatanakul W. Difficult-to-control asthma: epidemiology and its link with environmental factors. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;15(5):397–401.

Alangari AA. Corticosteroids in the treatment of acute asthma. Ann Thorac Med. 2014;9(4):187–92.

Walsh LJ, Wong CA, Oborne J, Cooper S, Lewis SA, Pringle M, et al. Adverse effects of oral corticosteroids in relation to dose in patients with lung disease. Thorax. 2001;56(4):279–84.

Loftus PA, Wise SK. Epidemiology and economic burden of asthma. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015;5(Suppl 1):S7–10.

Pawankar R. Allergic diseases and asthma: a global public health concern and a call to action. World Allergy Organ J. 2014;7(1):12.

Mansur AH, Srivastava S, Mitchell V, Sullivan J, Kasujee I. Longterm clinical outcomes of omalizumab therapy in severe allergic asthma: study of efficacy and safety. Respir Med. 2017;124:36–43.

Cisneros Serrano C, Melero Moreno C, Almonacid Sanchez C, Perpina Tordera M, Picado Valles C, Martinez Moragon E, et al. Guidelines for severe uncontrolled asthma. Arch Bronconeumol. 2015;51(5):235–46.

Global Initiative of Asthma. 2018 GINA Report, global strategy for asthma management and prevention. [cited 2018 24 Julio]; https://ginasthma.org/2018-gina-report-global-strategy-for-asthma-management-and-prevention/. Accessed 24 July 2018.

Guía Española para el Manejo del Asma (GEMA 4.2). 2017. http://www.gemasma.com. Accessed 15 May 2017.

Suzuki C, Silva LDN, Kumar P, Pathak P, Ong SH. Cost-effectiveness of omalizumab add-on to standard-of-care therapy in patients with uncontrolled severe allergic asthma in a Brazilian healthcare setting. J Med Econ. 2017;20(8):832–9.

van Nooten F, Stern S, Braunstahl GJ, Thompson C, Groot M, Brown RE. Cost-effectiveness of omalizumab for uncontrolled allergic asthma in the Netherlands. J Med Econ. 2013;16(3):342–8.

Levy AN, Ruiz GAAJ, Garcia-Agua Soler N, Sanjuan MV. Cost-effectiveness of omalizumab in severe persistent asthma in Spain: a real-life perspective. J Asthma. 2015;52(2):205–10.

Vennera Mdel C, Valero A, Uria E, Forne C, Picado C. Cost-effectiveness analysis of omalizumab for the treatment of severe persistent asthma in real clinical practice in Spain. Clin Drug Investig. 2016;36(7):567–78.

Sullivan SD, Turk F. An evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of omalizumab for the treatment of severe allergic asthma. Allergy. 2008;63(6):670–84.

Norman G, Faria R, Paton F, Llewellyn A, Fox D, Palmer S, et al. Omalizumab for the treatment of severe persistent allergic asthma: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2013;17(52):1–342.

Morishima T, Ikai H, Imanaka Y. Cost-effectiveness analysis of omalizumab for the treatment of severe asthma in Japan and the value of responder prediction methods based on a multinational trial. Value in health regional issues. 2013;2(1):29–36.

Dewilde S, Turk F, Tambour M, Sandstrom T. The economic value of anti-IgE in severe persistent, IgE-mediated (allergic) asthma patients: adaptation of INNOVATE to Sweden. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(9):1765–76.

Corren J, Casale T, Deniz Y, Ashby M. Omalizumab, a recombinant humanized anti-IgE antibody, reduces asthma-related emergency room visits and hospitalizations in patients with allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111(1):87–90.

Walker S, Monteil M, Phelan K, Lasserson TJ, Walters EH. Anti-IgE for chronic asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003559.

Rodriguez-Martinez CE, Sossa-Briceno MP, Castro-Rodriguez JA. Cost effectiveness of pharmacological treatments for asthma: a systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(10):1165–200.

McQueen RB, Sheehan DN, Whittington MD, van Boven JFM, Campbell JD. Cost-effectiveness of biological asthma treatments: a systematic review and recommendations for future economic evaluations. Pharmacoeconomics 2018;36:957. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-018-0658-x.

Schatz M, Kosinski M, Yarlas AS, Hanlon J, Watson ME, Jhingran P. The minimally important difference of the asthma control test. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(4):719e1–723e1.

Gisbert R, Brosa M. eSalud Healthcare cost database: Oblikue Consulting, S.L.. 2012. http://www.oblikue.com/bddcostes. Accessed 9 Sept 2015.

BotPlus: Healthcare Knowdlege database. 2016. https://botplusweb.portalfarma.com/. Accessed 18 May 2016.

Instituto Nacional de estadística (INE). 2016. http://www.ine.es/. Accessed 18 May 2016.

Korn S, Thielen A, Seyfried S, Taube C, Kornmann O, Buhl R. Omalizumab in patients with severe persistent allergic asthma in a real-life setting in Germany. Respir Med. 2009;103(11):1725–31.

Cazzola M, Camiciottoli G, Bonavia M, Gulotta C, Ravazzi A, Alessandrini A, et al. Italian real-life experience of omalizumab. Respir Med. 2010;104(10):1410–6.

Tzortzaki EG, Georgiou A, Kampas D, Lemessios M, Markatos M, Adamidi T, et al. Long-term omalizumab treatment in severe allergic asthma: the South-Eastern Mediterranean “real-life” experience. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2012;25(1):77–82.

Vennera MDC, Perez De Llano L, Bardagi S, Ausin P, Sanjuas C, Gonzalez H, et al. Omalizumab therapy in severe asthma: experience from the Spanish registry–some new approaches. J Asthma. 2012;49(4):416–22.

Schumann C, Kropf C, Wibmer T, Rudiger S, Stoiber KM, Thielen A, et al. Omalizumab in patients with severe asthma: the XCLUSIVE study. Clin Respir J. 2012;6(4):215–27.

Molimard M, de Blay F, Didier A, Le Gros V. Effectiveness of omalizumab (Xolair) in the first patients treated in real-life practice in France. Respir Med. 2008;102(1):71–6.

Lopez Tiro JJ, Contreras EA, del Pozo ME, Gomez Vera J, Larenas Linnemann D. Real life study of three years omalizumab in patients with difficult-to-control asthma. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2015;43(2):120–6.

Molimard M, Buhl R, Niven R, Le Gros V, Thielen A, Thirlwell J, et al. Omalizumab reduces oral corticosteroid use in patients with severe allergic asthma: real-life data. Respir Med. 2010;104(9):1381–5.

Barnes N, Menzies-Gow A, Mansur AH, Spencer D, Percival F, Radwan A, et al. Effectiveness of omalizumab in severe allergic asthma: a retrospective UK real-world study. J Asthma. 2013;50(5):529–36.

Rottem M. Omalizumab reduces corticosteroid use in patients with severe allergic asthma: real-life experience in Israel. J Asthma. 2012;49(1):78–82.

Subramaniam A, Al-Alawi M, Hamad S, O’Callaghan J, Lane SJ. A study into efficacy of omalizumab therapy in patients with severe persistent allergic asthma at a tertiary referral centre for asthma in Ireland. QJM. 2013;106(7):631–4.

Costello RW, Long DA, Gaine S, Mc Donnell T, Gilmartin JJ, Lane SJ. Therapy with omalizumab for patients with severe allergic asthma improves asthma control and reduces overall healthcare costs. Ir J Med Sci. 2011;180(3):637–41.

Brown R, Turk F, Dale P, Bousquet J. Cost-effectiveness of omalizumab in patients with severe persistent allergic asthma. Allergy. 2007;62(2):149–53.

Dal Negro RW, Tognella S, Pradelli L. A 36-month study on the cost/utility of add-on omalizumab in persistent difficult-to-treat atopic asthma in Italy. J Asthma. 2012;49(8):843–8.

Abraham I, Alhossan A, Lee CS, Kutbi H, MacDonald K. ‘Real-life’ effectiveness studies of omalizumab in adult patients with severe allergic asthma: systematic review. Allergy. 2016;71(5):593–610.

Domingo C, Pomares X, Navarro A, Rudi N, Sogo A, Davila I, et al. Omalizumab is equally effective in persistent allergic oral corticosteroid-dependent asthma caused by either seasonal or perennial allergens: a pilot study. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(3):521.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the study collaborators: Entrenas Castillo, Marta (1); Ferrer Galván, Marta (6); González García, Maite (12); Ignacio Barrios, Victoria Manuela (12); Medina, Juan Francisco (6); Muñoz Zara, Pilar (12); Pérez Fernández, Antonio Manuel (11); Romero Falcón, Auxiliadora (6); Sojo González, M. Agustín (9); Valenzuela Mateo, Francisco (3). The authors also thank GOC Networking for providing advice on statistics, methodology and editing the manuscript and Marta Pulido, MD, PhD, for editorial assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LME contributed to the study concept design, analysis and interpretation of results. All authors contributed to data acquisition and interpretation of results. All authors were involved in the preparation and review of the manuscript and approved the final version to be submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from Novartis Farmacéutica S.A.

Conflict of interest

Entrenas, Luis M: I have no conflicts of interest to declare. Casas-Maldonado, Francisco: I have no conflicts of interest to declare. Soto Campos, José Gregorio: I have no conflicts of interest to declare. Padilla-Galo, Alicia: I have no conflicts of interest to declare. Levy, Alberto: I have no conflicts of interest to declare. Álvarez Gutiérrez, F J: I have no conflicts of interest to declare. Gómez-Bastero Fernández, AP: I have no conflicts of interest to declare. Morales-García, Concepción: I have no conflicts of interest to declare. Gallego Domínguez, Rocío: I have no conflicts of interest to declare. Villegas Sánchez, Gustavo: I have no conflicts of interest to declare. Mateos Caballero, Luis: I have no conflicts of interest to declare. Pereira-Vega, Antonio: I have no conflicts of interest to declare. García Polo, Cayo: I have no conflicts of interest to declare. Pérez Chica, Gerardo: I have no conflicts of interest to declare. Martín Villasclaras, Juan José: I have no conflicts of interest to declare

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Independent Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital of Jerez on 13 January 2015.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Entrenas Costa, L.M., Casas-Maldonado, F., Soto Campos, J.G. et al. Economic Impact and Clinical Outcomes of Omalizumab Add-On Therapy for Patients with Severe Persistent Asthma: A Real-World Study. PharmacoEconomics Open 3, 333–342 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-019-0117-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-019-0117-4