From the start, the Attalids were city people. Philetairos was born in Tieion, a proud Greek city, staked out at the mouth of the river Billaios on the southern coast of the Black Sea. Pinched between semi-barbarous Bithynia and non-Greek Paphlagonia, the people of Tieion boasted of descent from Ionian Greeks of the city of Miletus. The mother of Philetairos was named Boa, an indigenous Paphlagonian name, but the city of his birth counted itself a Greek polis. When it successfully evaded absorption into Lysimachus’ new mega-city of Amastris, Tieion minted coins bearing the Greek for FREEDOM and joined Herakleia, Byzantium, Chalcedon, and Kios in the so-called Northern League, a formidable alliance of powerful Black Sea poleis.Footnote 1 One can imagine that a young Philetairos carried with him the urbane pretensions of the Hellenic outpost of Tieion, the city that he would have called his fatherland (patris), when he first arrived on the hilltop of Pergamon, as the treasurer charged with safekeeping 9,000 talents of silver for the king Lysimachus.

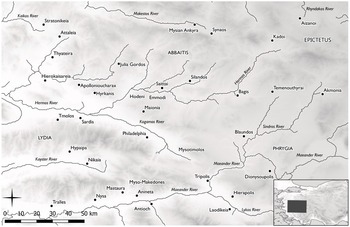

The Pergamon that Philetairos first encountered was as much an old fortress as a young polis. As a city, it lacked a storied past. In the Achaemenid period, it had not been a city at all, but rather the manorial citadel of the Gongylid barons, whom Xenophon in his Anabasis depicts lording it over the Kaikos Valley.Footnote 2 Indeed, Pergamon is absent from Herodotus’ list of the twelve Aeolian cities of mainland Asia Minor.Footnote 3 Yet it was precisely those cities, near at hand, which Philetairos soon began to cultivate from the perch of his fortress.Footnote 4 Within a few generations, Attalos I would refer to them all as the “cities under” him, the urban core of the early kingdom.Footnote 5 Though it was the second-century monarchs who made the city of Pergamon, in Strabo’s words, “what it now is,” the third-century Attalids took momentous steps to surround the citadel with the trappings of an estimable polis.Footnote 6 By origin, the Attalids’ was a city-state empire, sustained by taxes collected by other city-states, nourished on their cooperation, and glorified by their prestige. Once assigned their cis-Tauric, continental empire, Eumenes II and his brother must have drawn on these experiences in absorbing major urban centers such as Ephesus and Sardis. Yet cities were only one class of features on the map drawn up at Apameia. The Attalids were also assigned regions called “Lydia” and “Lykaonia,” two kinds of “Phrygia” (“Hellespontine” and the ominously named “Greater Phrygia”), a region known as the “Milyas,” and contested parts of “Mysia.” How were these thinly urbanized territories integrated into the Attalid state? How were these lands and populations rendered legible for Attalid administrators and tax men?Footnote 7

Contrary to expectation, it was not by urbanization that the Attalids achieved the deeper integration of Anatolia, which the Achaemenids and the Seleukids had not.Footnote 8 The importance of the cities of the great coastal river valleys is uncontestable. New rulers perforce engaged with them. However, the Attalids were also active at the uppermost reaches of those river valleys, at the headwaters of the Hermos (Gediz), for example, in the town of Kadoi, which gives its name to the modern river. There, in the second century, a visitor found a landscape bereft of cities. Understandably, the cities have shaped our view of the kingdom, for it is primarily through their decrees and coins, the stoas of the urban marketplaces and the statues of the poliad sanctuaries, that the story of Pergamon has been told. Indeed, Polybius lauds Eumenes II as his generation’s greatest benefactor of “Greek cities.”Footnote 9 Yet the city was only one settlement type among several, the polis only one of the different forms of political community with which the Attalids needed to interact. In some cases, from these towns, villages, and decentralized tribal confederations a new polis was born; more often, the Attalids managed to build places into their political economy without building a city. The Attalids did found cities; Antalya (Attaleia), the greatest port of Anatolia’s southern seaboard, still echoes their name. However, in contrast with the earlier Hellenistic kings of the age of Alexander and his Successors, who spent their Persian plunder so freely, the Attalids did not pay to herd large numbers of smaller settlements into imperial mega-cities. They also eschewed the costly and coercive tactics of rivals Philip V and Prousias I, who leveled and rebuilt, in their own image, the Propontic cities of Kios and Myrleia.Footnote 10 Instead, with typical agility and economy of effort, the Attalids drew people into their orbit without forcing them to move or change their way of life. Tellingly, recent excavations of a large cemetery in Antalya demonstrate continuity in occupation and burial practice from the third century to the second.Footnote 11

This chapter surveys the settlement landscape of inner Anatolia under the Attalids. Unsurprisingly, a hierarchy does emerge, with the polis planted firmly at the top.Footnote 12 What is surprising, however, is not just the range of polities to be reckoned with in the interior of the kingdom, but also the range of interactions taking place between the Attalids and non-Greek, nonpolis communities. Postcolonial Classics has taught us that the Greeks never monopolized power in the Hellenistic East.Footnote 13 Yet the most recent generation of scholarship on these kingdoms casts the polis as the privileged interlocutor of the king. It turns out that if a polis played its cards right, it could leverage its symbolic resources. The Anatolian interior, however, was filled with far fewer poleis than the Aegean coast. Since success depended on a rapid recognition of the tax base, the Attalids quickly shed their pretense. Each civic organism represented a unit of local support and a transit point for taxes. It mattered little whether the village was governed by an assembly modeled on Classical Athens or by a traditional council of elders. If the village wanted an assembly, with Athenian-style civic tribes to boot, the Attalids were happy to advise. In most cases, we in fact know absolutely nothing of how these communities functioned on the inside. Yet we can observe the process of their adhesion to Pergamon. Joining up with the Attalids did not mean relinquishing a fiscal territory and the prerogatives of a body politic. On the contrary, the very fact that these civic organisms held on to their own fiscal territories and maintained their own memberships is what keyed resource extraction and dialogue.

Still, certain towns and clusters of villages clamored for recognition as poleis, and the Attalids, hungry for honors and eager to set in place pliable institutions, then oversaw their transformation into “Greek cities.” What difference did the change of status make? In other words, what did it mean to be born a polis with Pergamene midwifery? Was the new title the sign of a new sense of cultural identity, the outcome or rather the beginning of a process of acculturation? It is doubtful whether the so-called birth of a polis meant that populations nucleated and new settlements instantly gained orthogonal streets and public and commercial squares. Rather, it seems that with the name “polis” the Attalids handed their subjects two gifts: an ideological defense weapon and a new set of institutions. For excluding their walls, the name “polis” was their greatest defense. It was tantamount to a human right in Antiquity, which, in theory, guarded against arbitrary exactions and punishments or forced labor, demanding dignity and equal treatment in any higher-order political community. It was a small price to pay for the Attalids, who now oversaw the installation of recognizable institutions, tried-and-tested methods of tax collection, and a clean conduit for redistribution.

The Bottom

To begin our survey of inner Anatolia at the bottom, with the weakest, and then progressively work our way up the settlement hierarchy, we must begin with the communities of peasants known by the crude term laoi (“the people”). These dependent villages of indigenous farmers were usually located within the boundaries of great estates. The estates belonged to courtiers, generals, or private landowners, the local powerbrokers who had survived regime change. Villages of laoi were also found on royal estates and scattered about less neatly defined royal domains like forests. Laoi were neither serfs nor slaves.Footnote 14 Nor, however, were they fully free: villagers’ mobility was hindered, though they might also find themselves summarily uprooted. The shadowy existence of the Anatolian laoi tends to register on our radar when an estate changed hands, and the new owner claimed the tax liabilities of their villages.Footnote 15 The owner, so to speak, of their taxes might be the king, a polis, a larger-order town, a private individual, or the nearby temple. For example, in a dossier of Seleukid-era inscriptions chiseled on the wall of the great Temple of Artemis at Sardis, the taxes due from villages on the estate of a man called Mnesimachos are transferred to the goddess along with the rest of his estate. The Lydian villagers owe taxes in cash, their labor, certain “wine-jars,” and still more levies on “the other products of the villages.”Footnote 16 It is unlikely that any laoi ever had any say in these transactions. At best, the village headmen may have received timely notice and a new destination address for the taxes. In a very fragmentary inscription recovered in the theater at Pergamon, an Attalid military colony of the mid-third century receives a number of gifts and privileges. The king awards his cavalrymen revenues, land to cultivate and land for homes, and with that land, apparently, “its people.”Footnote 17

From the Attalid perspective, each group of laoi possessed a territorial definition, but not a territory. Unauthorized movements of population disrupted tax collection and the cruel demands of corvée labor. Laoi lacked secure property rights, and though they were meant to stay put, the laoi held startlingly little control over the land under their feet. An intriguing and unique royal document from the hinterland of Aigai highlights the scope of their insecurity. The inscription is usually dated roughly to the third century, making Attalid authorship plausible. The curt tone of the memorandum signals orders for a group of laoi. It is a long list of taxes on everything from land to beehives – even the hunt is taxed at the rate of one leg per boar and one per deer. For certain work, the people are provided with tools at royal expense. Most importantly, they appear to have lost, no doubt by an unrecorded act of violence, the very means of subsistence. Mercifully, they now receive back lost land, vineyards, and houses, in sum, reads the text, “their property.”Footnote 18 As it stands, we cannot determine the identity of those who drove these peasants off their land. We should not rule out the possibility that it was in fact an arm of a Hellenistic state. We know that in a shake-up of settlement structure, the Attalids themselves cleared out two tiny villages of the Lydian forest called Thileudos and Plazeira.Footnote 19

The Ascendant Towns

Directly above the hapless laoi was a class of towns called in similarly unimpressive language the katoikiai (“the settlements”; singular katoikia).Footnote 20 The title sounds anodyne, but it conceals a partnership of fundamental importance for the Attalids. Historians have underestimated its significance because, like Polybius, they have tended to focus on Pergamon’s relationship with the polis. However, by means of direct access to the king and his court, representatives of these towns exercised real power. Indeed, it was to satisfy the needs of one katoikia, probably Apollonioucharax, that those laoi of Thileudos and Plazeira in the Lydian forest lost their land. Now, of the many towns called katoikiai in our sources, it is often unclear which were Attalid foundations, rather than inheritances from earlier empires. That said, such settlements seem to proliferate – in our sources, at least – across the Lydian countryside after 188 (Map 4.1). A denser network of agrarian settlements inhabited by would-be conscript soldiers helped both to maintain Pergamene military manpower and to expand the tax base. Colonization is a potentially misleading description of the phenomenon, for the population of these towns was probably of local origin, or in the case of the Mysians, made up of recent migrants from an adjacent upland ecological zone. The timing of the Mysian migration, like the authenticity of the claim of certain settlers to Macedonian identity, is difficult to determine. The more interesting questions pertain to what the Attalids stood to gain by shoring up these towns and fostering civic consciousness among their inhabitants.Footnote 21

The military character of the katoikiai has proven difficult to define. In part, this is because we can rarely pin down the location of towns known mostly from epigraphy, nor have we yet been able to conclusively match many toponyms to standing fortifications.Footnote 22 It also probable that the function of many settlements changed over time, as an early Hellenistic fortress and garrison developed into a full-fledged town by the second century. For the Attalids, the self-sufficiency of these agrarian communities was in fact crucial to their military value. Therefore, many towns occupied fertile plains. The inhabitants were registered for conscription; they were not a standing army maintained by the state.Footnote 23 Strategically, a dense belt of settlement formed across eastern Lydia, concentrating manpower where it was most needed: where the urbanized core of the empire met the stateless Anatolian hinterland, the approaches to the porous, ill-defined border with Galatia. It was a settlement policy of filling in blind spots.

The agricultural significance of the katoikiai was paramount. On the best land available, the Attalids nurtured client communities. We see this twin concern for keeping tabs on the soldiery and providing them with productive farms in one second-century Attalid’s letter to an anonymous katoikia (RC 51). According to a framework detailed in the letter, each soldier received a lot that contained two kinds of land: a larger part for arable agriculture and a smaller part for the vine. Interestingly, the lots themselves are not uniformly equal, but the larger lots seem to go to those who are registered as living on the land. In other words, the Attalids wanted to tie soldier-settlers to the land. Trust was at stake. Indeed, the availability and the quality of the land were crucial to the compact between king and settler. For example, Polybius describes Attalos I in 218 leading a trusting band of Galatians, the Tolistoagii, with their wives, children, arms, and equipment in tow, on a circuitous journey in search of a “fertile place” to inhabit.Footnote 24 Attalos was personally playing the part of land-distributor (geodôtês), an office twice documented in Lydia of the troubled 160s, but nowhere to be found in Seleukid records.Footnote 25 The king successfully carved out settlements for the Tolistoagii near the Hellespont, but not without paying a price. To win the acquiescence of the nearby cities of Lampsakos, Ilion, and Alexandria Troas, Attalos must have paid dearly, but it was with such bargains struck on the fly that an empire was founded and later expanded.

It is often supposed that a strategic, not an agrarian logic drove earlier Achaemenid and Hellenistic colonization of western Anatolia. It is asserted that the Seleukid colonies in Lydia, for example, straddled important highways, while Attalid sites are ostensibly off the beaten path. It is an attractive argument, which rightfully credits Pergamon with bringing more territory than ever before under state control. However, the evidence for this claim is far less secure than its almost axiomatic use nowadays suggests. It was an argument originally developed almost a century ago by Robert in a discussion of the (still unverified) location of Attaleia in the upper Lykos Valley.Footnote 26 According to Robert, the Attalids were principally concerned with the agricultural productivity of settlement sites. Therefore, he suggested, site distribution under the Attalids should bear little relation to strategic routes and passes. Yet that corollary claim does not stand up to scrutiny. Frank Daubner has recently restated the argument, claiming that most new Hellenistic settlements in Lydia are Attalid, but unlike the Seleukids, or even the Persians before, Pergamene towns were founded in fertile plains, at a remove from major roads.Footnote 27 He points to the Hyrkanian Plain, but also names Stratonikeia in the upper Kaikos Valley as a probable Attalid foundation. Persian activity, though, is evident in the very name of the great plain, not to mention sites therein such as Dareioukome. In fact, according to an attractive model proposed by Nicholas Sekunda, Achaemenid colonization in Lydia was also oriented toward agriculture. Achaemenid nobles drew on the usufruct of scattered villages; and the colonists per se were ex-mercenaries, not reserves, who received land as a reward for past service. Their dispersed village communities and Iranian identities did not survive the Spartan incursions of the early fourth century.Footnote 28

As for Lydian Stratonikeia, if it is in fact to be located at the village of Siledik, it actually occupied a strategic position astride two major routes into the plain of Kırkağaç: one south to Thyateira and another west to Pergamon. To be fair, we should not discount the quality of the surrounding land. Ephebes known as the Stratonikeians from an evidently well-known plain known as the Indeipedion were registered in the capital.Footnote 29 The site was both defensible and propitious for farming. Still, most damning to Robert’s influential thesis is archaeologist Christopher Roosevelt’s observations in his detailed study of long-term settlement patterns in Lydia. He points out that in the absence of more secure spatial data, the pattern which emerges right across the Persian and Hellenistic periods is consistent: settlements tend to be sited in defensible positions at the edge of fertile plains, near perennial routes of communication and mountain passes.Footnote 30

Rather, what is distinctive about the Attalids is just how much they relied on these towns of modest size, mixed military-civilian and non-Greek character to sustain their rule. They multiplied in the second century in the same east Lydian/south Mysian zone that Aristonikos was to make his final redoubt after the fall of the dynasty. The region proved to be the rebel’s greatest bulwark because earlier Attalids had cultivated it. That concern for the long-term agricultural prosperity of this kind of community is perceptible elsewhere, too, for example, from the Kardakon Kome near Telmessos in Lycia. A letter of Eumenes II to his official Artemidoros addressed the lamentable condition of the settlers.Footnote 31 When, in 181, Eumenes, in his own words, set about investigating the settlers’ fitness to pay taxes, he found their orchards sparse and their land poor. In fact, some men had already fled the place and consequently evaded state control. Those who remained in the village had agreed to purchase much needed land from a local lord named Ptolemaios, but ultimately failed to pay up. Eumenes rescued the community by ordering the land transferred to the settlers’ possession. Ultimately, he lowered the villagers’ tax rate because they were “weak and weighed down by their private affairs (ta idia).” Through a pattern of interaction that would recur across Attalid Anatolia after 188, the villagers of Kardakon Kome gained lands and secured property rights. For the success of their private affairs was of great interest to the king, who hoped to tax it one day soon. Wherever needed, land was purchased, confiscated, or transferred to sustain the katoikiai. It seems too that the inhabitants of katoikiai held whatever land they acquired with royal aid on privileged terms, as a “sovereign possession,” according to one document.Footnote 32 Fascinatingly, the Attalids alone seem to have extended to small farmers the private property rights that other rulers reserved for the henchmen whom they gifted with great estates; and Pergamon now conceded to the village what had been conceded, traditionally, to the polis.Footnote 33

Just like the Seleukids and Achaemenids, who bequeathed an unknown number of these towns, the Attalids counted on a reserve of soldiers settled in the Anatolian countryside, such as those who commemorated their return from a campaign in the Chersonese and Thrace with a dedication at Sındırgı.Footnote 34 What changed now was that more of these soldiers were native farmers, rather than guards imported from the Near Eastern imperial center. Compare the vision of Seleukid colonization under Antiochos III, ca. 200 BCE, contained within Flavius Josephus’ report of the settlement of Jews in katoikiai emplaced in restless parts of Lydia and Phrygia.Footnote 35 There, Jewish guards (phylakes) and their households are transplanted from faraway Mesopotamia. Certain elements do accord with the Attalid model, in particular, the distribution of two kinds of land and building materials, the civilian tinge to the place, and the emphasis on the bond of trust between colonists and king, reminiscent of Attalos and his Galatian clientele on the Hellespont. Yet the Seleukid colonies are explicitly described as garrisons (phrouria) established among populations in revolt, quite unlike the isolated Pergamene garrison found on the Yüntdağ.Footnote 36 Seleukid settlers could even come to dominate a nearby polis, as happened when neighboring colonists inserted themselves into a treaty between the cities of Magnesia-under-Sipylos and Smyrna.Footnote 37 We have no evidence that the Attalids ever installed communities as overseers.Footnote 38

The task now assigned to these towns, old and new, was different and more important. They were the eyes and ears of the king in the deeper countryside that had not yet known state power, and they were rewarded for this service handsomely. Just a hint of that promotion and those strengthened ties to the monarchy is contained in the name of one town near Satala in Lydia’s upper Hermos valley, the “katoikia of the kings,” presumably, the brothers Eumenes II and Attalos II.Footnote 39 It is difficult to imagine Seleukid settlers, whether in Lydia or in Jerusalem’s Akra citadel, taking on such airs. In the decentralized Attalid state, the katoikiai became increasingly autonomous and increasingly capable of serving a fiscal function, as tax collectors in the remote countryside and as a fixed address for redistribution. To serve these functions, a town did not need coinage or walls, though many must have possessed a fortified enceinte or a sturdy tower. In fact, there was no urgent need for nucleation.Footnote 40 Likewise, the town did not need an assembly or a council, but any form of representation before the king would do. What they needed was a territory and a body politic. On a delimited, dependent territory, the katoikia raised taxes for the Attalids, a portion of which it kept for its own people, the body politic that also stood to gain from any royal kickbacks.

Subject to each Attalid katoikia was a dependent territory, often with laoi living on it, structurally, analogous to a Classical polis with its dependent territory (chora) and dependent villages (demes; kômai). In fact, across rural Anatolia of this period, we find articulated a newfound expression of territory, or one at least publicized for the first time in epigraphy. As Schuler explains in his exhaustive study of these communities, when we consider them from the perspective of their own self-representation – as opposed to the hegemonic perspective of the polis – much more about their senses of place and identity comes into focus.Footnote 41 These Attalid towns joined a range of rural communities in asserting their territoriality.Footnote 42 Under the shadow of Rhodes, for example, the upland peripolia of Lycia and Caria behaved similarly.Footnote 43 One could see here an aspect of a growing cottage industry in small-scale civic identities. This is a development from the bottom-up over which the Attalids had no control, but it represented an opportunity. Thonemann has drawn attention to the late Attalids’ curious habit of detaching land from the royal domain and devolving it onto cities and towns.Footnote 44 They sacrificed aspects of sovereignty in these places for the sake of raising higher, more predictable revenues, or perhaps any taxes at all. However, of Thonemann’s six cases, in only three was the Attalids’ beneficiary a polis. As civic organisms, the katoikiai were evidently seen as fit to receive dependent territories, as well as grants of territorial inviolability.Footnote 45 One even wonders if the Attalids oversaw the occasional transfer of territory to a katoikia at the expense of a rival polis, as may have occurred around Lake Apolloniatis, in the territories of Apollonia-on-the-Rhyndakos and Miletoupolis.Footnote 46 Thus, even without further urbanization or an upgrade to the status of polis, the Attalids possessed ready-made vehicles for territorial integration.

One can also perceive here an increasing formalization of the body politic of these communities, which was not without consequence for the Attalids. Membership in the katoikia came to be defined more rigorously, meaning that the in-group could claim a larger share of the spoils of empire; the village could finally partake of the traditional leisure (scholê) of the city. Such is the implication of the plea of the settlers at Apollonioucharax who petitioned Eumenes II for building materials to rebuild houses torched in the Galatian Revolt.Footnote 47 The translation of the passage has vexed commentators, but may be understood to highlight an unsuspectingly salient political identity in the Attalid kingdom. The text reads: “Regarding the houses in the suburb (proastion), which were burned and pulled down, (we request that) it be seen to that since we are co-citizens (dêmotai), some grant be provided for their reconstruction.” Apparently, certain people who could claim membership in the katoikia dwelt outside its fortified core on exposed, vulnerable terrain before the walls or ramparts.Footnote 48 To Eumenes II or his official, it may not have been obvious why royal building crews should rebuild these particular homes, for so much stood in ruins. After all, they were located at some remove from the main settlement. So the emissaries of Apollonioucharax made their case, arguing in solidarity that “since we are the same people/citizens (dêmotai)” help was in order.Footnote 49 In other words: these are Attalid people and must be saved. Membership in the katoikia meant something.Footnote 50

Naturally, we can begin to identify in this period a sharper profile for the rural body politic. In sleepy towns, dormant identities were awakened, amplified, or even invented. Take the example of a settlement called Kobedyle in the rural Kogamos Valley in eastern Lydia. In their decree, the settlers call themselves “the Macedonians from Kobedyle,” though it is not clear whether they are colonists of a defunct regime, newly settled emigrants fleeing the Antigonid collapse, or simply Attalid soldiers trained to fight in the Macedonian manner.Footnote 51 In any case, the settlers date their decree by the regnal year of Eumenes II, declaring their allegiance and framing a context for their politics. Puzzlingly, the Macedonians award honors to a man whom they call their “citizen” (politês). Though not so named in the short, fragmentary text, Kobedyle is plainly a katoikia and not a polis.Footnote 52 In what sense, then, could it claim a citizenry? Getzel Cohen writes, “The use of the term πολίτης suggests that by the time of the inscription, namely 163/2 B.C., the inhabitants of Kobedyle had become citizens of a polis. However, the identity of this polis is unknown.”Footnote 53 Yet the document more likely suggests that the term “citizen” was not the exclusive preserve of the polis. And who was to say that it should be? Kobedyle had not overstepped, at least not by the reckoning of the Attalids, for whom stronger civic identities were a boon. Cohen’s interpretation ignores the logic of the grammar, which makes of the honoree a citizen of the body politic honoring him – a co-citizen.Footnote 54 It is not difficult to understand how a town like Kobedyle could manifest citizens if we keep in mind the fluidity of real-world politics. The ever-expanding civic consciousness of rural Anatolia gelled perfectly with the Attalid style of governance.

We can compare the similarly idiosyncratic language of the honorary decree for Nikanor son of Nikanor, found in modern Badınca, ca. 5 km from Alaşehir (Philadelphia).Footnote 55 An anonymous and atypical body politic awards the honors: τὸ κοινὸν τῶν πολιτῶν (association or council of citizens?). Georg Petzl conjectures that the honoring body was the katoikia of Adruta, which we know belonged to Philadelphia.Footnote 56 This may mean that the citizenry of the town, though subordinate to a royal foundation, maintained their own functioning civic institutions. On the other hand, Cohen writes, “From the mention of politai and ephebes we may conclude that even at this early stage in its development Philadelphia had the accessories of a polis.”Footnote 57 However, there is no reason to assume that the document belongs to Philadelphia, or even that it dates to a time after the accession of the city’s namesake Attalos II (159). It is just as likely that Philadelphia did not yet exist, but that one of the towns later subsumed by that city had selectively adopted certain institutional indicia of a polis. Instead of seeing the anomalous “koinon of citizens” as a feature of a young polis, yet unformed, we should see it as another sign of the diversity of civic organisms and growing civic consciousness in the Anatolian countryside of the late Hellenistic period.

Temple People

In much of the countryside, signal communal activities continued to take place according to the rhythms of the agricultural calendar around indigenous or thinly Hellenized shrines and temples. Governors and garrison commanders vested local priests with power over large sectors of the rural population. Priests, then, demanded taxes and perquisites, but could also offer the farmers protection in return. The impact of Alexander’s conquest on the power of these so-called Anatolian temple-states and their sacred villages is much debated. While some surely perished, others survived, either bound to a polis – often enough, uncomfortably and insecurely – or as independent entities. Of the independent variety, alongside a major, regional center such as Pessinous in eastern Phrygia, we must also consider small temple-towns, individual villages attached to a single cult and its priesthood. At both ends of that scale, the evidence suggests that the Attalids made use of the native cults as an interface with marginal populations. Moreover, where a rearrangement of the rural settlement structure seemed propitious, cult sites made for sturdy platforms on which to erect new cities.Footnote 58

Across the Hellenistic East, the kings, who were often the newcomers, contended with the power of age-old temples and religious authorities. This is the form of interaction that gave us the Rosetta Stone, the Maccabean Revolt, and which resounds in cuneiform astronomical diaries from Babylonia. One of several ways in which the Attalids, who were not foreign to Anatolia, differed from their rivals was by their ability to penetrate deeper into out-of-the-way temples and beneath the hieratic elite. A remarkable dossier of Attalid correspondence illustrates a distinctive pattern. For example, in the Upper Kaikos Valley, the Attalids granted tax exemptions in 185 to a group of villagers attached to an obscure sanctuary of Apollo Tarsenos.Footnote 59 Keeping with traditional decorum, the villagers accessed the royal bureaucracy through their high priest. Afterward, however, village and priest passed a decree together in response to the benefaction, demonstrating the kind of burgeoning civic consciousness that we find in other small towns. Under Attalos III, villagers at Hiera Kome (“sacred village”), on the frontier with Caria, were more precocious: they contacted the king directly with their concerns.Footnote 60 Finally, Attalos III may also have confirmed the inviolability of a sanctuary of Anaitis-Artemis in the Hyrkanian Plain.Footnote 61 Again, it was the villagers, “those around the goddess,” who sent ambassadors bearing documents and requests.Footnote 62 The Attalids, it seems, managed to diffuse the threat of so much social power concentrated in rural sanctuaries. Properly cultivated, the temples represented not an alternative, but rather a branch of the state.

Certain indigenous shrines seem to have formed the core of the new settlements that the Attalids constructed in the hinterland. The tantalizingly laconic sources for these foundations hint at an effort to anchor new cities in old cults. For example, a Pantheon shrine, a sanctuary of All Gods, may have formed the nucleus of the city of the Pantheôtai established in Lydia.Footnote 63 The ecumenical nature of the cult seems to have appealed to the Attalids, ever eager to attract the greatest number of adherents to their cause. In addition, the theophoric names of new cities of the interior, such as Phrygian Dionysoupolis and Hierapolis on the Upper Maeander, hearken back to earlier forms of political organization under the authority of god and priesthood. There are good reasons to believe that Hierapolis was a Pergamene refoundation.Footnote 64 In the case of Dionysoupolis, Stephanus of Byzantium preserves in its bare bones the origin story for the city. Eumenes II and his brother Attalos founded Dionysoupolis after discovering an archaic cult statue (xoanon) of the god Dionysus on the spot. It is a self-serving legend, one which the Attalids themselves perhaps invented, but it is also a sophisticated fabrication. It is worth asking: Precisely which god Dionysus did Eumenes and Attalos find in the region of the Çal Dağ and Çal Ova? On the one hand, it is a curious coincidence that the Attalids discovered a pristine image of one of their dynasty’s tutelary divinities in a region targeted for colonization. The cult of an Orphic and theatrical Dionysus Kathegemon (“the Guide”), as he was known on the citadel of Pergamon and, increasingly, in many parts of the kingdom, including urbanized Phrygia, was tied to king, court, and old Greek cities like Teos. On coins of Dionysoupolis’ civic mint, this god appears. On the other hand, a very different, rural, Hittite-version of Dionysus, associated with Zeus, storms, and springs, remained current among the highlanders of Phrygia well into the Roman period. The logic of the story allows for either version of Dionysus to take center stage. On a bend in the great river, the Attalids had likely chosen a spot for their city with links to the cult of an Anatolian Dionysus. The foundation story reflects a bold attempt to introduce dynastic piety under cover of a local deity.Footnote 65

Among the cult centers of inner Anatolia, none grew more powerful in this period than the sanctuary of Cybele Agdistis at Pessinous on the notional border between Phrygia and Galatia. Attracting Attalid interest from an early date, it was the source of the Magna Mater cult that the Attalids adroitly transferred to Rome during the crucible of the Hannibalic Wars.Footnote 66 The Settlement of Apameia placed the sanctuary under the direct control of Pergamon, though we cannot be sure it remained so. Certainly, the Attalids strove to make diplomatic partners of its priests and to construct its territory as a buffer zone fronting the land of the Tolistobogii.Footnote 67 Painstaking archaeological detective work has reconstructed the human landscape around Attalid Pessinous. The built sanctuary, in fact, seems to have been a contrivance of Eumenes II or Attalos II. Its predecessor, the pre-Hellenistic, Phrygian sanctuary of Matar, may have sat somewhere on the sacred rocks of the Sivrihisar Mountains. Historically, the most important settlements of the region were not in the Gallos Valley. The choice of the site at modern Ballıhisar seems to have been administrative. It lacks the Cybele cult’s distinctively rocky geology, and archaeologists have found scant remains of Phrygian occupation; the first signs of settlement actually date to the second and first centuries BCE. The excavated remains do confirm Strabo’s report of Attalid building in the sanctuary (temenos). Yet if urbanization should rank among this dynasty’s preferred tools for integrating resource-rich stretches of inner Anatolia into a nascent empire, we would expect its effects to register here. Did the Attalids intervene decisively in the settlement history of Pessinous, urbanizing the sanctuary and its environs?Footnote 68

A recent discovery presents the first unimpeachably direct evidence of Attalid activities in and around Pessinous after 188. It is an inscribed royal letter of the future Attalos II addressed to a local military commander named Aribazos, found at Ballıhisar in 2003 (D15). The fragment lacks a date, but the context seems to be the immediate aftermath of the Attalid takeover. Aribazos appears to be an ex-Seleukid officer, a traditional local powerbroker, as his Persian name implies. Over and above an undelivered gift promised to junior officers, Aribazos makes three demands of Attalos: confirmation of his estates, an enhanced position in the new Attalid bureaucracy, and directions for mercenaries under his command. It is in his description of his relationship to the rank-and-file soldiers in his district that the character of settlement at Pessinous emerges. For Aribazos identifies himself as the commander of two groups of soldiers, the katoikoi of Amorion and of certain Galatians, the former mercenaries, stationed in a “place” (topos) called Kleonnaeion.Footnote 69 Surprisingly, the toponym Pessinous is absent. This has led Thonemann to make the ingenious suggestion that Kleonnaeion is Pessinous or, rather, that alongside the temple community existed a second polity, this one with a Greek name and appearance. The arrangement may strikes us as strange, but the heterogeneous inhabitants of the Hellenistic East found it perfectly normal.Footnote 70 A series of coin-types also shows twin settlements at the site, a priestly polity and the place called Kleonnaeion, perhaps named after a Macedonian general. In short, the new royal letter shows that the Attalids inherited this complex tableau.

Nothing, however, indicates that the Attalids rearranged settlement around what was termed a chorion (rural stronghold) during the campaign of conquest in 207.Footnote 71 Perhaps, with Pergamene support, Kleonnaeion eventually grew into a small polis, but its coins alone and the preliminary results of excavation are inconclusive proof.Footnote 72 If indeed this was a far more sanguine case of twin-track, bicultural settlement than that which arose next to mighty Near Eastern temples in Jerusalem, Babylon, or Rough Cilicia, all under Seleukid rule, it was the result of the Attalids’ much more cautious approach. Unlike in those cases, in which the Seleukids devised or were convinced to plant a polis under the priests’ noses, in the case of Pessinous and Kleonnaeion, the Attalids were content to maintain the status quo during a limited, but still decades-long period of influence over the sanctuary. For the Attalids, all that distinguished Kleonnaeion from the nearby katoikia of Amorion was its proximity to Pessinous. It was just another rural soldier-town without a large urban core, but the shrine lent it administrative importance. It is probably not an accident that Aribazos declares himself registered among those at Kleonnaeion. He in fact tells us himself that Kleonnaeion was not a polis, but rather a topos (“place”), employing the standard military-administrative term for extra-urban sites.Footnote 73 This was a key administrative hub in a dispersed landscape, parasitically attached to the central node of a regional network. Merely strengthening it meant bringing more of rural Anatolia into its first sustained contact with a Hellenistic state.

The Sons of Telephos

So declares a gabled stele now in Bursa, Turkey, recovered in the late nineteenth century in the town of Kirmasti, today Mustafakemalpaşa, near the site of ancient Miletopoulis on the lower Rhyndakos. Beneath that text are two recessed panels. In one, a bull is led to sacrifice as a towering Zeus (?) looks on (Fig. 4.1).Footnote 74 In the other, two men huddle together, one clothed and leaning on a staff. The other figure is fully nude, in the guise of the hero, leaning on what appears to be a spear. A large drinking cup sits on the ground. Crammed below the images, the following epigram is scrawled in rude letters:

If Doidalses, who often on account of his athletic victories donned mirthful crowns on his head, had a fatherland, which was distinguished for its strong young men, then his deeds would be recorded alongside the great feats of Herakles. Therefore, the sons of Telephos, having placed him on par with noble men, glorify him with an everlasting homage.

At first glance, this object and its poem, an awkward piece of pop-literature with a dissonantly Homeric vocabulary, look like artifacts of the almost absurdly fierce hometown pride that characterized Greco-Roman civilization. His fatherland? Doidalses lived in a hamlet outside the city of Miletoupolis. His fatherland was a katoikia. His deeds like Herakles? The comparison seems specious. What league did he even play in? Certainly not a Panhellenic one – was he even Greek? Local Greeks claimed kinship with Miletus, but there were also Bithynians and Mysians among the population of so-called Hellespontine Phrygia in the second century. As noted since discovery, the name Doidalses is Thracian or Bithynian. Finally, what sense did it make for this village, which evidently lacked a name worth mentioning, to honor its compatriot in the name of “the sons of Telephos”? Why would these villagers highlight the heroic ancestor of the people of Pergamon, whose saga was illustrated on the inner frieze of the Great Altar?Footnote 75

Figure 4.1 Hellenistic grave stele of Doidalses from Mustafakemalpaşa.

On closer inspection, the stele housed in Bursa no longer seems generic, but in fact illustrative of a specific moment in the history of Anatolia. Again, we find people outside the cities brandishing their own civic identity. The anonymous town here is a famous fatherland (patra), and its inhabitants gather to praise a victorious athlete in good, classical form. Doidalses’ name sounds like a Thraco-Bithynian spin on Daedalus, but this was a time of shifting ethnic identities. Of the identity of Doidalses’ community, Elmar Schwertheim has suggested that is a katoikia of Mysians.Footnote 76 Indeed, this was the time when a broad spectrum of indigenous people living under Attalid rule came to call themselves “Mysians.” Many were soldiers organized on the katoikia model, but civilians also counted among their ranks. This was a vast population spread across a region stretching from the Cyzicene peninsula to eastern Lydia. Gradually drawn into the Attalids’ web, by the end of the dynasty, Mysian youth had even gained access to the gymnasium at Pergamon.Footnote 77 The most important point of administrative contact we can trace was the federal entity (probably Koinon) of the Mysians of the Abbaitis, but other regions and tribes, such as the “Hellespontine Mysians,” may have been similarly organized.Footnote 78 Their koinon consisted not of cities, but rather of a number of rural districts (dêmoi), which grouped settlements around a central place. As the epigram indicates, the supremely flexible myth of Telephos, a figure at once the “barbarian-speaking Greek” and an archetypal Mysian, provided these populations with a heroic and Hellenic ancestry.Footnote 79 Just as importantly, it tied their identity to the Attalids’. The stele of Doidalses is an artifact of rural life under the Attalids, evidence that Pergamon achieved a far-reaching integration of its new territories, both ideological and institutional, without herding people into cities.

Pergamon’s debt to Mysia is well known. In fact, the Attalids themselves publicized it soon after arriving on the Panhellenic stage. On Delos, Attalos I erected a very unusual statue group, the so-called Teuthrania Monument, which depicted two or perhaps all three generations of royalty, while also thematizing the landscape of the Kaikos Valley, which is to say, the part of Mysia best known from Greek literature.Footnote 80 The statue group included a number of eponymous heroes: Midios (Midapedion), son of Gyrnos (Gryneion) and Halisarna; Teuthras (Teuthrania) son of Midios and Arge; and Phaleros, son of Ib[…] and Rhaistyne, daughter of Selinus (the river god).Footnote 81 This seems to be a major departure from the conventions of the genre of royal ancestors (progonoi) monuments.Footnote 82 In place of queens and Olympian ancestors such as Herakles, all of which may have appeared on a contemporary Antigonid monument also on Delos, a network of Mysian toponyms was personified. The explanation for this strange choice is not that the Attalids were “bourgeois” rulers depicting a maximally elaborated family tree, nor that as “liberals” they were representing their kingdom like a polis with a hinterland (chora), though Gyrnos was associated with the founder-hero (ktistês) Pergamos. Rather, as Andreas Grüner has shown, the Teuthrania Monument alludes to a network of settlements, mostly, but not exclusively poleis, which the earlier lords of the valley, the Gongylids and the Demaratids, had first bound together into a unified political geography.Footnote 83 If the Arkadian Telephos had afforded these families of exiles a link back to Greece, the Mysian Teuthras had helped them to fashion a micro-empire in their adopted homeland. As has been noted, the dynastic myth of Telephos and his stepfather Teuthras had nothing to do with the site of Pergamon, but rather that of modern Eğrigöl Tepe. What was appropriated then from the previous dynasties was both a regional fiefdom and a Mysian pedigree. Before the international audience on Delos, the Attalids did not emphasize Heraklid/Telephid descent, for their Greekness was not at stake. Rather, in a manner that anticipates the inner frieze of the Great Altar, they showcased the landscape of Mysia. Given the early date of the monument, it is important to keep in mind that when the Attalids arrived on the international scene, they arrived as Mysians. As Pierre Debord underscores, the site of Pergamon was one of the mytho-historical centers of Mysia, a fact which does not in any way impugn Attalid Hellenicity.Footnote 84 Survival as a first-order Mediterranean power depended on solidarity with this population and therefore the promotion of a Mysian identity.Footnote 85

Politically, the administrative unity of a region known as Mysia, indeed one centered on Pergamon, may already have existed under the satrap Orontes, ca. 360.Footnote 86 However, as a cultural geography, the boundaries of Mysia were always vague and shifted over time. On the one hand, the low-lying areas near the coast tend to show up earlier in the Greek sources, such as the Kaikos Valley in the southwest and the Hellespontine plains around Daskyleion and Cyzicus in the north. For example, in the Athenian tribute list of 454/3, the Μυσοί are a community on the Propontic coast of Asia Minor.Footnote 87 Yet much of historical Mysia lay at higher elevations and scarcely enters the record before the Attalids (Map 4.1). The upland regions contained the central plains around modern Balıkesir and the Savaştepe Valley, as well as the rougher country to the east, the upper valleys of the ancient Makestos and Hermos, up to Kadoi across Mount Dindymos from Phrygian Aizanoi. In addition, Mysians wandered into what epigraphers refer to as “northeast Lydia,” though just when migration south of Mount Temnos began is anyone’s guess. While Aeschylus describes Mysians by Mount Tmolos in the vicinity of Sardis in 472, the major wave of migration seems to have begun later, perhaps during the third century.Footnote 88 The result was ethnogenesis and the emergence of federalism among the Mysians of the Abbaitis, a region that encompassed both sides of Mount Temnos (Demirci Dağ), the Simav basin, the upper Makestos, the upper but now also the middle Hermos. For the Attalids, the economic importance of their regional hinterland must have been profound. The silver deposits of Balya lay in Mysian country between the upper Kaikos and the Balıkesir plain. Even at higher elevations, good land for growing grain was in abundance. The place name Kadoi seems to preserve an Anatolian root for grain.Footnote 89 Lower down in the Katakekaumenê of “northeast Lydia,” wine was produced for export.Footnote 90

Scholars have tended to see Mysia as a land of brigands and hill people but, first of all, a land of laborers.Footnote 91 One scholar goes so far as to call the “human resources of rural Mysia” one of the “two lungs of the Attalid monarchy,” along with the old Greek cities of the coast.Footnote 92 For their part, the Mysians provided indispensable manpower for the entire enterprise. From early on, they fought the wars and defended the winnings. Teamed with a broader local milieu of Thraco-Bithynians, as well as natives of Pergamon and of Cyzicus, they garrisoned the capital as well as far-off possessions like Aegina.Footnote 93 When we find lists of Attalid soldiers’ names, for instance, the 141 recorded in full at the sanctuary of Thermon in Aetolia or those attached to a citizenship grant for a garrison near Delphi, Mysians make up a near-majority.Footnote 94 Like all Hellenistic kings, the Attalids employed mercenaries, especially Galatians, but the contingents of Mysoi would seem to have been regular levies. In other words, with material and symbolic leverage, the Attalids managed to compel these warriors to join up. In fact, though their fame as fighters spread abroad, Mysians very infrequently emigrated into Hellenistic armies outside Asia Minor.Footnote 95

By contrast, Mysia’s debt to Pergamon is less often acknowledged. The Mysians stood to gain greatly from the growth of the Attalid empire, which perhaps explains why, returning from distant theaters of war, they remained at home. The Mysians’ quiet fulfillment of their end of the bargain is revealed in the aforementioned dedication from Sındırgı, set up in 145 by demobilized “soldiers who had crossed to the Chersonese and places in Thrace.”Footnote 96 They use the regnal year for a date, but explicit praise for the king is absent.Footnote 97 Signs of sycophancy are absent because the relationship was genuinely beneficial to both parties. The lightweight Attalid state was dependent on this source of manpower, but Mysia flourished under Pergamon, reaching its apogee.Footnote 98 The evidence for this claim is not an uptick in city-building, for the region remained rural. Rather, we can point to the assertion and embellishment of Mysian identity, the sudden appearance of civic institutions capable of producing decrees and coinage, and an increase in the number of people laying claim to the mantle of Mysia. An elevated status is nowhere more visible than in the domain of genealogy. The myth of Telephos, who helped the Greeks on their way to Troy, long linked to Mysia, gained a new salience within Attalid state religion.Footnote 99 It seems too that the Mysians now began to press on their connection to Troy itself. For example, like many in the Mediterranean, they could look to a brief mention of an ancestor in Homer’s Iliad. Theirs was a certain Chromis, named as a leader of the Mysians at Troy.Footnote 100 The federal assembly of the Mysians of the Abbaitis went so far as to honor their Homeric ancestor as a forefather (propatôr).Footnote 101 Interestingly, they called him Chromios. Was it a slip of the chisel or a conscious play for a bigger name? Since the name Chromios belonged to a Trojan prince, a son of Priam and a companion of Hektor, the upgrade certainly suited the socially ascendant Mysians.Footnote 102

Gravestones by nature bear out strong statements of identity, as a life is summed up in just a few words. It is telling, then, that a late Hellenistic or early Roman epitaph from rural Mysia reads, “So long! (Here lies) Menekrates son of Timarchos, a Mysian who fell in battle.”Footnote 103 Menekrates or his survivors were not simply engaging in the conventional naming practice of adding what scholars call his “ethnic,” his political affiliation to his father’s name. He was asserting in death a heroic archetype, the “fallen Μύσος,” which he expected to resonate with passersby. The choice of this mortuary pose implies an astounding development of Mysian identity. First, very simply, it implies that Mysian ethnogenesis had taken place. Second, the existence of the archetype implies that the martial exploits of these Mysians had been embedded in heroic narrative. The image evoked is a quotation from that narrative, which had become by Menekrates’ time a genuine meme. Both are the result of interaction with the Attalids. An ethnographer of Hellenistic militaries is hard-pressed to fix the geographical origin of the Mysians, not only due to the usual gaps in our knowledge, but since so many different groups and individuals began to wear the name in this period.Footnote 104 The process of ethnogenesis had clearly begun much earlier, but now it accelerated to breakneck speed. New groups like the Masdyênoi appear in the record, already attached to the banner of Mysia, as if no other path to peoplehood existed.Footnote 105 In the northern region around modern Yalova, one group even claimed to be Pratomysioi – the “real Mysians,” evidence of the newfound social currency of the ethnicon.Footnote 106 It is especially telling of the tempo of ethnogenesis at this moment that one community in Lydia named themselves the Myso-Makedones and another called itself the town of Mysotimolos. The one is a graft on top of an older identity tied to Mount Tmolos.Footnote 107 The other is an attempt to partake of the newfound Mysian glory without renouncing the older prestige identity of the Macedonians. These hybrid names may evidence migration and resettlement, but they certainly also echo a new and increasingly prestigious ethnic identity in the countryside.Footnote 108

In particular, the startling appearance of the Myso-Makedones, a people positioning themselves as both the traditional and the emergent ethnic power in the countryside, forces us to consider what a remarkable rehabilitation of the image of Mysia the Attalids had effected. From the indelible image of Telephos in rags, an invention of Euripides that found its way into Aristophanes’ play Acharnians, to the pithy comedian Menander’s insulting expression “the last of the Mysians” (Μυσῶν ὁ ἔσχατος), we find a sustained line of contempt. The region of Mysia was considered a veritable wasteland. It was a defenseless land ripe for plunder, leaderless while Telephos was away on his hero’s journey. For example, the Athenian politician Demosthenes contended that were it not for the Athenians’ resistance, the Persians would have subjected Greece to “a proverbial ‘looting of Mysia (Μυσῶν λεία).’” Here, worse than simply stuck outside “Greece,” Mysia is stuck on the wrong side of history. In fact, these Anatolian highlands had long been vulnerable to the predation of Greeks and Persians. Marching his Spartans to the Hellespont, Agesilaus had raided the forests of Mysia for conscripts. Further, the region had long been a source for slaves. A manumission decree of 179 from Delphi for a Mysian named Apollonios recalls that past. Yet in the Attalid era, the Mysians were no longer the hunted. On the contrary, they were the hunters.Footnote 109

The Çan Sarcophagus, a piece of Achaemenid military art, provides a useful point of comparison (Fig. 4.2). Discovered in an elite tomb in the Troad’s Granikos Valley, it belonged to an early fourth-century Iranian or Iranized noble, who wished to be depicted in death as a hunter. Two painted reliefs are preserved on the sarcophagus, one a scene of hunting animals, stag and boar, the other a battle scene. In each, the main subject is shown stabbing a victim in the eye, in one panel, a boar, in another, a human, trapped beneath the rider on horseback. The lightly armed figure in the battle scene is a defeated Mysian. The juxtaposition of the images then implies a macabre analogy: as he hunted the stag, so too did the occupant of the sarcophagus hunt Mysians.Footnote 110 To understand that cruel gesture, one must examine the relationship of the Achaemenid state to this population. Xenophon consistently portrays the Mysians, along with the Pisidians, as the most vexing inhabitants of Achaemenid Anatolia. He saw them as independent, but also menacing. Xenophon reports frequent Mysian raids on the king’s land, not loose imperial control, but open enmity. The Oxyrhyncus Historian writes, “Many of the Mysians are autonomous and do not answer to the king.”Footnote 111 Thus, for an Achaemenid baron like the one buried in the Çan Sarcophagus, interaction with the Mysians amounted to frequent, nearly ritualized violent clashes. As the Spartan officer Klearchos and the satrap Tissaphernes agreed, the point of any interaction with them was to mete out violent discipline.Footnote 112

Figure 4.2 The Çan Sarcophagus from the Granikos Valley, early fourth century BCE.

While the Seleukids succeeded in drawing individual Mysians and bands of mercenaries into their service, they failed to fully integrate communities. The Persians’ thorny “Mysian problem” becomes less visible after Alexander, but the essentially antagonistic structure of interaction persists. There can be no doubt that the Seleukids made use of the human resources of Mysia. We find Mysians next to Achaios at the siege of Selge and alongside Antiochos III at the Battle of Magnesia. Further afield in the Levant, we find entire contingents of Mysians in the armies of Antiochos IV. Yet the Seleukids’ reach into rural Anatolia was limited. Large populations must have evaded state control. The Pamukçu stele of 209, which treats the appointment of Nikanor as high priest, indicates the presence of the Seleukid state in the very heart of Smooth Mysia. How far beyond the penumbra of an administrative outpost was this presence felt? What was the cost of control for the Seleukids? A model, at least, presents itself in the story of Josephus on the establishment of Mesopotamian Jewish colonists in “the most difficult places” of rural Phrygia and Lydia. The mechanisms of control appear to have been costly indeed and highly coercive, pitting colonists against natives. Josephus’ story is all about trust: Antiochos III places his trust (pistis) in the Jews, the outsiders whom he imports and equips with arms, making them the watchmen for restless Anatolia.Footnote 113

Taking a different tack, the Attalids placed their trust in the Galatians, Phrygians, Lydians, and, especially, in the Mysians themselves, who now changed from mercenaries into conscripts.Footnote 114 By devolving authority, the kings both economized on coercion and gained access to stores of resources hitherto untapped. Uniquely among the Hellenistic rulers of Anatolia, the Attalids granted villages – and not just cities – full property rights over the land.Footnote 115 Throughout rural Mysia, the Attalid experience produced increasingly formalized, recognizably Hellenistic-style polities. The Mysians, perhaps in tandem with the poorly understood but increasingly vocal Phrygians of the Epictetus – and all those who rallied to these identities – were the privileged partners of the Attalids, both at home and abroad. It is probably not an accident that we find a proudly self-identifying Mysian on Aegina in this period. A gravestone records the name of a certain Xenokles the Mysos, probably an agent of the Attalid occupation of the island.Footnote 116 A growing dossier of inscriptions documents nascent institutions, which would have provided Pergamon with an unprecedented reach into rural Anatolia. The Mysians of the Abbaitis now came to possess a council (boulê), an assembly (dêmos), and a mint. A decree in honor of Philomelos son of Ophelas, from the vicinity of Silandos, showcases an extensive civic armature.Footnote 117 Philomelos, who is described as a co-citizen (politês), served his fatherland (patris) on embassies and with liturgies. As a biographical encomium, the decree would not be out of place in many a late Hellenistic polis.

Equally conventional of civic life are the bronze coins, which are well represented in major collections and must have contributed significantly to the monetization of the region.Footnote 118 Coins associated with a federal mint issuing under the names “the Mysoi” (ΜΥΣΩΝ) and “the Mysoi Abbaeitai” (ΜΥΣΩΝ ΑΒΒΑ, ΜΥΣΩΝ ΑΒΒΑΙΤΩΝ) burst into circulation late in the Hellenistic period (Fig. 4.3).Footnote 119 The bronzes appear in three types, most commonly featuring a laureate Zeus on the obverse, a winged fulmen surrounded by an oak wreath and text on the reverse.Footnote 120 One does not need to search too far to find nearly identical coins, for example, those of the polis of Apollonia-on-the-Rhyndakos, with ΑΠΟΛΛΟΩΝΙΑΤΩΝ framing the winged fulmen in place of ΜΥΣΩΝ.Footnote 121 With an ecumenical Zeus as their primary icon, capable of serving double duty as an Anatolian sky god, along with the winged fulmen, perhaps copying a Macedonian shield emblem, these Mysians were fitting right in.Footnote 122 A second type seems to bear more idiosyncratic images: a female deity (?) crowned with stephanê and an enwreathed labrys, the woodsman’s axe.Footnote 123 Finally, a third type, consisting of a young Herakles donning the lion’s skin helmet on the obverse, and the demigod’s club on the reverse, itself draped with the lion’s skin, expresses strong affinities with Pergamene coinage and the Attalid house.Footnote 124 The draped club of Herakles, in particular, is precisely the image that the Attalids had placed on their own coinage, the fractions of their new cistophori.Footnote 125

Figure 4.3 Late Hellenistic bronze coin of the Mysoi Abbaeitai.

All this minting represents, on the one hand, the newfound prestige of Mysian identity, an ethnogenesis that probably accelerated through the process of federalization.Footnote 126 On the other hand, minting of this sort presupposes the existence of sturdy institutions of public finance, a civic toolkit. These coins are not the occasional issues of a local warlord. This is the money of a Mysian polity, as both its text and the uniformity of the mintmarks declare. On this reckoning, coinage flows from the formalization of traditional modes of governance and cooperation. It is a common feature of the polis, but was at no point in the history of money its exclusive preserve. Support for this claim can be found elsewhere in the numismatic record for inner Anatolia under the Attalids and in the wake of their collapse. It is at this point in history that a number of rural communities appear for the first time in coinage. The Kaystrianoi, of the eponymous Kayster Valley in Lydia, like the Mysians of the Abbaitis, also minted second-century bronzes marked with the Attalids’ signature draped club of Herakles.Footnote 127 Two other groups, the Epikteteis (Phrygia) and the Poimanenoi (“shepherds”) of the lower Aisepos on the conventional, arbitrary dating of their coins, began minting soon after the Attalid collapse.Footnote 128 The formalization of their institutions could very well have begun earlier. The Zeus/thunderbolt coinage of the Poimanenoi bears such a striking resemblance to the bronzes of the Abbaitis that it may originate in the same historical context.Footnote 129 This barrage of coinage echoes the politicization of the Anatolian countryside, a development from which the Attalids, first, and the Romans, later, stood to gain.

In the signal case of the Abbaitis, we know that politicization took the form of a federal koinon comprised of different sub-polities (dêmoi). While the constituent dêmoi passed decrees, they were in fact not poleis, but rather rural districts, networks of small settlements oriented around a central place. The koinon federalized the villages.Footnote 130 This is important to emphasize because the distinctly pro-Attalid communities of the Abbaitis never became a union of poleis. In certain places, such as Kadoi, (Mysian) Ankyra, and Synaos, an early Roman city eventually succeeded the central settlement of the former district, but this was only after the political concept of the Abbaitis had dissipated following the Mithridatic Wars.Footnote 131 Another such place was Gordos, south of Mount Temnos, between Thyateira and the river Hyllos, garrisoned first by a Seleukid commander (hêgemon) and later by a Pergamene “hêgemon of Mysians.”Footnote 132 Something had changed. Under the new regime, the “[district of the] Mysians of the Abbaitis in Gordos (οἱ Μυσοὶ Ἀββαεῖται [?] ἐν Γόρδωι)” bestowed honors on a benefactor linked to the Attalids.Footnote 133 The inscription juxtaposes the Mysians in the district of Gordos, a member dêmos district, with the “entire people (σύμπας δῆμος),” that is, with the totality of the Mysians in the koinon of the Abbaitis.Footnote 134 Archaeology demonstrates the privileged position that rural Mysians achieved in the Attalid kingdom. In a 2012 salvage excavation in modern Gördes, a late Hellenistic chamber tomb built from rough-cut stone was uncovered 1 km from the later site of the Roman city of Julia Gordos. It contained three skeletons, and a child’s remains were found in an adjacent cist grave. Among the contents of these tombs was a trove of second-century Pergamene dishes, demonstrating close economic ties and the metropolitan tastes of the rural Mysian elite.Footnote 135

Another key document is a late Hellenistic funerary stele from Yiğitler in the Demirci district, attesting four different Mysian dêmoi of the Abbaitis, those of the Lakimeni, Hodeni, Mokadeni, and Ankyrani, all described in spatial terms as the people around (peri) a particular place.Footnote 136 These sub-polities of the Mysian koinon would seem to have encompassed many villages and a polis-sized territory.Footnote 137 The process of federalization not only accelerated ethnogenesis; it seems to have given the Mysians a new sense of territoriality.Footnote 138 By helping put the Mysians on the map, the Attalids revealed and came to know these new territories for themselves. This was achieved without resorting to the laborious task of founding cities. Indeed, such confederations now proliferated on both sides of the Maeander in rural Anatolia. At times, smaller communities must have joined to achieve recognition or escape domination. Pergamon as well as Rhodes were surely also responsible for aggregating the rural population into more malleable units.Footnote 139 Whatever the impetus, the end result brought ever larger amounts of territory into administrative contact with the state. Yet if its ethnic and political landscape changed, the settlement pattern of Mysia remained starkly rural.

Already in 218, we find the desire of the Attalids to integrate the Abbaitis to their urbanized, coastal core in Aeolis. Attalos I had engaged the Gallic Aigosages during the War with Achaios, and he first used them to secure the cities of Kyme, Myrina, Phokaia, Aigai, and Temnos. Next, he continued inland toward Thyateira. Polybius provides a description of the king’s show of force in the countryside:

Continuing his progress and crossing the river Lycus he advanced on the Mysian communities (κατοικίαι τῶν Μυσῶν), and after having dealt with them reached Carseae. Overawing the people of this city and also the garrison of Didymateiche he took possession of these places likewise, when Themistocles, the general left in charge of the district by Achaeus, surrendered them to him. Starting thence and laying waste the plain of Apia he crossed Mount Pelecas and encamped near the river Megistus (Makestos).Footnote 140

Though the expedition of Attalos I may have proved successful only as a recruiting and plundering tour, Eumenes II was able to target and secure these same territories in the Peace of Apameia. As Robert first pointed out, the κατοικίαι τῶν Μυσῶν were hamlets and remained so for much of history.Footnote 141 The French epigrapher was convinced that Attalos had headed north from the Lykos near Thyateia to the upper Kaikos. From there, he would have entered the pass of Gelembe, continuing north toward the Balıkesir Plain, an area which was urbanized only in the second century CE under Hadrian. Passing the mining district of Balya, Attalos would have then entered Hellespontine Phrygia, effectively touring what Robert and early travelers considered the most accessible parts of rural Mysia. However, seeing no strategic or political value in these communities (even the minerals), Schwertheim preferred to locate them hard by the Hellespontine cities – the katoikiai of the athlete Doidalses.Footnote 142 Both interpretations seriously underestimate the Attalid ability to touch the most remote parts of the Abbaitis and bundle them together with hoary Teuthrania into a single Mysian kingdom. Now, Johannes Nollé has redrawn the route, which could have departed from the Gelembe pass and reached Sındırgı on the north side of Mount Temnos. On this reckoning, the army of 218 would have here entered the upper Makestos, marched the length of the Abbaitis, and finished by plundering the Phrygian Plain of Apia.Footnote 143 After 188, Eumenes II would return, but not as a city builder. We are thus forced to contemplate a full-scale ideological and administrative integration that reached deep into the countryside and preserved a traditional pattern of settlement.

The Birth of a Polis

So far, our survey of the countryside of the Attalid kingdom has highlighted small communities with a large sense of self-importance. With their own territories, revenues, citizenries, and royal subsidies, towns and cities of the post-Apameian kingdom achieved an unprecedented degree of cohesion and recognition. In the countryside, Eumenes II and his brother Attalos interacted with a broad spectrum of civic organisms. The polis, the notionally autonomous city-state on an archaic Greek model, with its council and assembly, laws and norms, fictitious tribes of citizens, magistrates, coins, and walls, was just one type. Long the power brokers of Hellenistic monarchies, these cities now seem to have lost their monopoly on unmediated contact with the kings, as more and more of Anatolia’s inhabitants were formally introduced to the state. Had the polis finally died? Quite the opposite: the ascendant towns and tribal polities now sent embassies to the Attalids, begging to be recognized as one, and recent epigraphical discoveries in Turkey even show us what the birth of a new polis looked like. Aristotle, if he had returned from the dead, would have been slightly puzzled by a Greek city of the second century BCE; certainly, though, he would have recognized it. The idea of the polis as a set of institutions and a cultural identity was still alive and well. Moreover, in practical politics, the name clearly carried weight. Yet to complete our survey of the settlement structure of Pergamene Anatolia, we need to know why, with political identities more fluid than ever, a semi-Hellenized community might still transform itself into a polis. What was at stake? And for the Attalids, what was gained and what was lost by acceding to these requests? What did it mean to be born a polis under Pergamon?

With a mounting body of evidence, we can now connect a number of Anatolian micro-histories to the high political history of the Mediterranean. The most colorful is that of Toriaion, an obscure Seleukid katoikia in Phrygia Paroreios, in the plain of Ilgın, not far from the road from Philomelium to Iconium, which ultimately led to the Cilician Gates and Syria.Footnote 144 In 1997, a long inscription was discovered at Mahmuthisar, containing a dossier of three royal letters, the correspondence of the new ruler Eumenes II and the community of Toriaion (D8). The text makes the historical setting explicit. It is the immediate aftermath of the Attalid takeover, with the Treaty of Apameia still fresh in mind. Betraying a measure of insecurity, Eumenes boasts that his bundle of gifts is no empty or illusory touch of grace (charis), but a grant founded on Roman arms and diplomacy.Footnote 145 Belatedly, Toriaion, which soon again slipped back into obscurity, has now achieved minor fame, as the first site to document a process so often effaced across the Hellenistic world. From a soldier-settler town of a mixed milieu of Graeco-Macedonian colonists, Phrygians, and Galatians – a key ambassador bears the Celtic name Brennos – Toriaion was now promoted to a polis. In the first letter, Eumenes addresses himself to “the settlers,” while in the second and third, his interlocutor is the council (boulê) and assembly (dêmos) of the Toriaitai. Yet the change here was more than titular and by no means just skin deep. The transformation of Toriaion did not take place in discourse alone, an exercise in “code-switching.” Rather, the town-cum-polis received an itemized list of new institutions per their initial request: a constitution (politeia), their own laws (idioi nomoi), a council, an assembly, and magistracies, and of course also a gymnasium. Finally, to top it all off, the Toriaitai requested and received “as much as is consistent with these things.”Footnote 146

As much as is consistent with polis-style institutions – a curious periphrasis; or is it, as much as is consistent with being a polis? We must try to follow the king’s train of thought. On the one hand, Eumenes defers explication to forthcoming letters, which, as we quickly learn, hammer out the details of Toriaion’s fiscal liabilities and privileges. To become a polis was to be more deeply integrated into the fiscal system of the Attalid state, but also to strike a fiscal bargain. On the other hand, Eumenes is at a loss for words. The rhetoric here gestures at an implicit contract between king and city, a nod to notoriously slippery notions like “freedom” (eleutheria) and “autonomy” (autonomia). The king binds himself. He vows to respect the ill-defined sovereignty of the polis. In this way, the Attalids abjured the more coercive forms of leverage. However, they simultaneously produced a much more robust civic organism, now filled with added citizens. Presumably, the more nebulous territory of the katoikia was expanded and clarified. Collection of certain taxes was ceded to polis administrators. Even the lower tax rate worthy of a polis could still bring in more revenues, as the Toriaitai, for their own ends, eagerly exploited a windfall of dominance over the neighboring Ilgın plain.Footnote 147 The Attalids had even more to gain by designing the new polis from the ground up. All of the new city’s laws and thus the final shape of its new institutions were to be submitted to the king for review, lest any contradict the interests of Toriaion. In fact, the stone reads “lest any contradict our interests,” as a felicitous and all-too-telling mason’s error transmitted the royal “we.”

Eumenes then makes a fascinating suggestion: if needed, he is prepared to mail Toriaion its laws – and with them, the blueprint for a new council, assembly, boards of magistrates, and civic tribes – each prepackaged and ready-made. The Attalids had them all in stock! This allowed the monarch to shape the new city to fit a radically decentralized fiscal system and to plant seeds for a new imperial culture. Unlike some earlier Hellenistic monarchs, the Attalids seem to have attended to this work “in-house,” rather than farming it out.Footnote 148 In a similar fashion, Antiochos IV, whom the Attalids had helped establish on the Seleukid throne, dispatched a lawgiver to Jerusalem, the mysterious Geron the Athenian, a royal functionary charged with overhauling that community’s institutions and stubborn sense of self, playing midwife for the birth of Antiocheia-in-Jerusalem.Footnote 149 Unfortunately, the Attalids’ interventions are only alluded to in Eumenes’ offer to Toriaion. Yet we may catch a further glimpse in a decree from Pergamon concerning Akrasos in rural Mysia. A group calling itself “the Macedonians around Akrasos” honored a very highly placed courtier of Eumenes II named Menogenes son of Menophanes for his goodwill toward them and toward the king. Like the Toriaitai, these Macedonians were probably former military reserves of the Seleukids, poised to take on the mantle of the polis in the new Attalid state. They had a special relationship with Menogenes, who is styled both the king’s intimate and his bodyguard.Footnote 150 One could see in the Attalid courtier Menogenes, then, a parallel for Antiochos IV’s Geron the Athenian: if not an authoritarian lawgiver, then the administrative tutor to a new polis.