Introduction and Theoretical Framework

In 2017, the United Nations estimated that the number of migrants living outside of their birth country was 258 million. Over the past decade, this figure has been increasing by about 2 percent a year. Though this might seem like a relatively small increase in total numbers given the world population, it is still a significant population movement. Many, if not most, of the migrants leave their birth countries to earn money and send it home to support families. The 2017 estimate of these remittances is about US 500 million dollars. It is surely much higher now. Also, many migrants come from low income countries, and the remittances are often a significant fraction of the GNP of these countries, often providing a tax base sufficient to support not only their families but also the elites. Between 50 and 60 percent of the migrants go to high-income countries.

A particularly poignant example is the story of Nepali workers in Malaysia (Awale, Reference Awale2016). This reporter described the plight of Nepali workers in Malaysia and other Gulf countries. About 20 percent of the 28 million people of Nepal work outside Nepal, in India, Malaysia, and the Gulf countries. The 5.6 million migrant workers of Nepal contribute 25 percent of Nepal’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) through remittance.

In Malaysia alone there are 700,000 Nepalese, which is the second largest migrant population there after Indonesia. They contribute 40 percent of the remittance money received by banks in Nepal. It has been reported that about 3,000 Nepali workers have died in Malaysia in the last twelve years, most of them from what is called Sudden Unexpected Death Syndrome (SUDS), many of heart attacks. Such deaths of Nepali workers have also been reported in Gulf countries like Qatar and Saudi Arabia. Since it is culturally inappropriate to perform autopsy in Nepal, and people accept death as karma, the cause of death is often not known. People from the mountain regions of Nepal may not be able to adapt to the hot and humid climate of Malaysia, and this gets compounded with intercultural, work-related, and social issues that aggravate stress levels. The growing migration-related work and health issues can be addressed to some degree by research and intercultural training, which is completely lacking for the most part.

Beyond the issues faced by economic migrants such as the Nepalese, there are intra-country migrants. In China over 200 million each year make the trek from their villages and farms to the large cities for jobs and back again. Some do it each week, while others spend longer periods of time at their jobs in the cities. These migrants do not appear in any migratory database, yet they face many of the same issues as those who do appear (Landis, Reference Landis2011; Xu & Palmer, Reference Xu and Palmer2011).

In addition to the large number of international migrants, approximately 71 million have been forcibly displaced from their homes and wound up as refugees. Of the 71 million, a little over 41 million were internally displaced, 26 million became refugees outside of their country of origin, and about 3.5 million sought asylum. Of the displaced individuals, 57 percent came from just three countries: Syria, Afghanistan, and South Sudan. Of the refugees, at least half of them are under the age of eighteen. In most cases, asylum seekers presented themselves as intact families. But in at least one case the families were split apart while their petitions for asylum were considered.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development has a commitment to leave nobody behind. The Agenda calls our attention to the impact of migration, whether voluntary or forced, on both countries of origin and settlement. This impact is not only economic but also includes social, physiological, and psychological aspects. All of these aspects require careful and unique attention to intercultural training approaches. Such is the overriding goal of this book.

Next, we will summarize theories of intercultural training. These will include the contributions of Triandis, Berry, Gudykunst, Milton Bennett, as well as the present editors. After that, we will outline the structure of the handbook by noting highlights from each of the chapters.

Globalization has led to increased interconnectedness among nations and we are much more interdependent than we were in the past (Landis, Reference Landis2008). This interdependence requires us to work with people from different cultures, and it also requires many of us to live in cultures far away and quite different from our own. Despite the similarities offered by technology and urban centers, differences persist, and the vision of a homogeneous world is quite unlikely and perhaps flawed. The variety of religions and languages present in the world today offers ample evidence that, if anything, human kind loves diversity. So we need to prepare ourselves to have a meaningful dialogue with people from different cultures to help each other solve our problems and also to learn from each other. Intercultural training as a field of research has become all the more relevant in today’s shrinking world.

Just as we are all lay social psychologists, all of us interculturalists – those who have spent some time away from home in a foreign culture – are also lay intercultural trainers; we can teach what we have learned just like any other knowledge or skill. However, since intercultural training has developed a rich literature as an academic discipline, which is grounded in theory, it offers an opportunity to researchers and professionals to provide a systematic approach to developing, implementing, and evaluating intercultural training programs. This chapter intends to contribute to the extant literature by providing a theoretical framework for the systematic development of intercultural training programs, which can be used both in professional training and in academic courses.

Four major reviews of the field of intercultural training (Bhawuk & Brislin, Reference Bhawuk and Brislin2000; Bhawuk, Landis, & Lo, Reference Bhawuk, Landis, Lo, Sam and Berry2006; Landis & Bhawuk, Reference Landis, Bhawuk, Landis, Bennett and Bennett2004; Warnick & Landis, Reference Warnick and Landis2015) have helped synthesize and extend the field of intercultural training in the new millennium. Bhawuk and Brislin (Reference Bhawuk and Brislin2000) provided a historical perspective tracing the evolution of the field, and concluded that the field has always been theory driven (Fiedler, Mitchell, & Triandis, Reference Fiedler, Mitchell and Triandis1971; Hall, Reference Hall1959, Reference Hall1966; Triandis, Reference Triandis, Brislin, Bochner and Lonner1975). They noted that in recent times it had become more so with the integration of culture theories (Bhawuk, Reference Bhawuk1998, Reference Bhawuk2001; Bhawuk & Brislin, Reference Bhawuk and Brislin1992; Brislin & Yoshida, Reference Brislin and Yoshida1994a, Reference Brislin and Yoshida1994b; Cushner & Brislin, Reference Cushner and Brislin1997; Triandis, Brislin, & Hui, Reference Triandis, Brislin and Hui1988). Landis and Bhawuk (Reference Landis, Bhawuk, Landis, Bennett and Bennett2004) presented a number of nested models leading to a comprehensive theoretical framework, such that through a program of research the framework could be evaluated by testing each of these models. Bhawuk, Landis, and Lo (Reference Bhawuk, Landis, Lo, Sam and Berry2006) synthesized the fields of acculturation and intercultural training, breaking new theoretical grounds for the development of various intercultural training strategies, and also presented its applicability for training military personnel, which followed on the work of Landis and colleagues at the Defense Equal Opportunity Management Institute and the Army Research Institute (Dansby & Landis, Reference Dansby, Landis, Landis and Bhagat1996; Landis & Bhawuk, Reference Landis and Bhawuk2005; Landis, Day, McGrew, Miller, & Thomas, Reference Landis, Day, McGrew, Miller and Thomas1976). This chapter notes the major contributions of these reviews, and further builds on them by synthesizing various theoretical ideas to propose an approach to intercultural training that is grounded in theory and can be utilized by business and government or non-government organizations.

Theory Building in Intercultural Training

A review of the field of intercultural training shows that it has been led by stalwarts like Edward Hall, Harry Triandis, Richard Brislin, Dan Landis, and Bill Gudykunst, who helped the field grow with an emphasis on theory building from its earliest days. It is notable that Hall (Reference Hall1959, Reference Hall1966) presented both a theory of culture and how it could be applied to train people to be effective while working abroad. Triandis along with his colleagues not only invented the culture assimilator (sometimes called the intercultural sensitizer), but presented many theoretical frameworks to provide the foundation of intercultural training as well as to develop and evaluate culture assimilators and other training programs (Triandis, Reference Triandis1972, Reference Triandis, Brislin, Bochner and Lonner1975, Reference Triandis1977, Reference Triandis1994, Reference Triandis, Fowler and Mumford1995a, Reference Triandis1995b; Triandis, Brislin, & Hui, Reference Triandis, Brislin and Hui1988; Fiedler, Mitchell, & Triandis, Reference Fiedler, Mitchell and Triandis1971). Brislin not only presented the seminal books on intercultural training (Brislin & Pedersen, Reference Brislin and Pedersen1976; Brislin, Reference Brislin1981), helping the crystallization of the field, but also coedited the first handbook (Landis & Brislin, Reference Landis and Brislin1983), the first cultural general assimilator (Brislin, Cushner, Cherrie, & Yong, Reference Brislin, Cushner, Cherrie and Yong1986; Cushner & Brislin, Reference Cushner and Brislin1996), and two volumes of exercises in which each exercise was grounded in a theory (Brislin & Yoshida, Reference Brislin and Yoshida1994a, Reference Brislin and Yoshida1994b; Cushner & Brislin, Reference Cushner and Brislin1997).

Landis founded the International Journal of Intercultural Relations in 1977 and continued to edit it until 2011. This journal is dedicated to building international understanding through intercultural training, which meets high standards of scientific rigor. Landis also developed many specialized culture assimilators including ones for use in the US military (Landis & Bhagat, Reference Landis and Bhagat1996; Landis, Day, McGrew, Miller, & Thomas, Reference Landis, Day, McGrew, Miller and Thomas1976), coedited three editions of the Handbook of Intercultural Training (Landis, Bennett, & Bennett, Reference Landis, Bennett and Bennett2004; Landis & Bhagat, Reference Landis and Bhagat1996; Landis & Brislin, Reference Landis and Brislin1983), convened a committee to create the International Academy of Intercultural Research in 1997, and served as its Founding President. Gudykunst contributed by developing theories of intercultural communication and applying them to the field of intercultural training (Gudykunst, Reference Gudykunst2005), and also organized the first conference of the Academy in 1999. Of course, other researchers (e.g., John Berry and Milton Bennett) and practitioners (e.g., Sandra Mumford Fowler, George Renwick, Janet Bennett) have also contributed to the field significantly in many other ways, but the contribution of these researchers especially deserves to be noted for their theoretical contribution.

Bhawuk and Brislin (Reference Bhawuk and Brislin2000) reviewed the literature and traced the historical evolution of the field over the past fifty years. They noted that the culture assimilators were still being used and researched (Albert, Reference Albert, Landis and Brislin1983; Cushner & Landis, Reference Cushner, Landis, Landis and Bhagat1996) – whereas, though simulation programs continue to be developed and used for intercultural training, they are not subjected as much to evaluation – and that there were many more tools, like the Intercultural Sensitivity Inventory and the Category Width, available for the evaluation of intercultural training programs. They noted two measure evaluation reviews, one by Black and Mendenhall (Reference Black and Mendenhall1990) and the other by Deshpande and Viswesvaran (Reference Deshpande and Viswesvaran1992), which showed that intercultural training programs do have positive outcomes for the trainees, but that long-term effectiveness has yet to be established. Black and Mendenhall (Reference Black and Mendenhall1990) reviewed 29 studies that had evaluated the effectiveness of various training programs, and concluded that, because of cross-cultural training provided to participants, there were positive feelings about the training they received, improvements in their interpersonal relationships, changes in their perception of host nationals, reduction in “culture shock” (even though this is a phenomenon that has yet to be firmly established Oberg, Reference Oberg1960; Ward, Reference Ward, Landis, Bennett and Bennett2004) experienced by them, and improvements in their performance on the job, establishing the general effectiveness of intercultural training programs. These findings were further supported in a meta-analysis of twenty-one studies in which the effect of cross-cultural training was examined on five variables of interest: self-development of trainees, perception of trainees, relationship with host nationals, adjustment during sojourn, and performance on the job (Deshpande & Viswesvaran, Reference Deshpande and Viswesvaran1992). Thus, the effectiveness of intercultural programs has stood various independent evaluations (see also meta-analysis by Morris & Robie, Reference Morris and Robie2001). However, Mendenhall, et al. (Reference Mendenhall, Ehnert, Kühlmann, Oddou, Osland, Stahl, Landis and Bennett2004) presented evidence that tempered the positive findings of the earlier studies and indeed pointed to the relatively moderate amounts of variance accounted by the training.

Triandis (Reference Triandis, Fowler and Mumford1995a) noted that, in general, field studies (which normally do not have control groups), but not the laboratory studies, have shown positive effects of cross-cultural assimilator training on most of the above mentioned variables. However, in a recent laboratory study comparing three types of culture assimilators with a control group, Bhawuk (Reference Bhawuk1998) found that a theory-based Individualism and Collectivism Assimilator (ICA) had significant effects on a number of criterion measures such as Intercultural Sensitivity Inventory, Category Width measure (Detweiler, Reference Detweiler1975, Reference Detweiler1978, Reference Detweiler1980), attribution making, and satisfaction with training compared to a culture-specific assimilator for Japan, a culture-general assimilator (Brislin et al., Reference Brislin, Cushner, Cherrie and Yong1986), and a control group. It must be noted that few studies have used behavioral measures over and above paper and pencil type dependent variables (Landis, Brislin, & Hulgus, Reference Landis, Brislin and Hulgus1985, and Weldon, et al., Reference Weldon, Carlston, Rissman, Slobodin and Triandis1975, are the exceptions), thus raising questions about the impact of culture assimilators on the actual behaviors of trainees outside of the training environment.

Bhawuk and Brislin (Reference Bhawuk and Brislin2000) noted that behavior modification training was one of the new developments in the field. Behavior modification training is necessary for habitual behaviors that people are not usually aware of, especially behaviors that are acceptable, even desirable, in one’s own culture, but which may be offensive in another culture. For example, in Latin American cultures, people give an abrazo or an embrace to friends, but this is not an acceptable form of behavior in the United States; or, in Greece, when people show an open palm, called moutza, they are showing utmost contempt, and not simply waving or saying hello (Triandis, Reference Triandis1994). A moutza needs to be avoided, whereas an abrazo needs to be acquired. There are many examples of such behaviors, and the only way to learn them is through behavior modeling, by observing a model do the behavior and then practicing the behavior many times. Despite its theoretical rigor and practical significance, this method has not been used much in cross-cultural training programs because it is expensive, requiring a trainer who constantly works on one behavior at a time. The work of Renwick (Reference Renwick, Landis, Bennett and Bennett2004) and other trainers exemplifies a similar approach.

Harrison (Reference Harrison1992) examined the effectiveness of different types of training programs by comparing groups that received culture assimilator training (i.e., Japanese Culture Assimilator), behavioral modeling training, a combined training (i.e., behavioral modeling and culture assimilator), and no training (i.e., control group). He found that people who received the combined training scored significantly higher on a measure of learning than those who were given other types of training or no training. This group performed better on the role-play task compared to the control group only, but not to the other two groups. This study provides further evidence for the impact of assimilators on behavioral tasks.

Bhawuk and Brislin (Reference Bhawuk and Brislin2000) noted another development that deals with the role of culture theory in cross-cultural training (Bhawuk, Reference Bhawuk1998; Bhawuk & Triandis, 1996a), and the development of a theory-based culture assimilator, which is based on the four defining attributes and the vertical and horizontal typology of individualism and collectivism (Triandis, Reference Triandis1995b; Bhawuk, Reference Bhawuk1995, Reference Bhawuk1996, Reference Bhawuk2001). Bhawuk and Triandis (1996a) proposed that culture theory could be used effectively in cross-cultural training. Bhawuk (Reference Bhawuk1998) further refined this model by integrating the literature on cognition and stages of learning, and presented a model of stages of intercultural expertise development and suggested that a theory-based assimilator using fewer categories is likely to be more effective because it does not add to the cognitive load experienced during a cross-cultural interaction. He carried out a multimethod evaluation of cross-cultural training tools to test the model (Bhawuk, Reference Bhawuk1998), and found that trainees who received the theory-based Individualism and Collectivism Assimilator (ICA), compared to a culture-specific assimilator for Japan, a culture-general assimilator (Brislin et al., Reference Brislin, Cushner, Cherrie and Yong1986), and a control group, were found to be significantly more interculturally sensitive, had larger category width, made better attribution on given difficult critical incidents, and were more satisfied with the training package. The findings of this study show promise for using over-arching theories like individualism and collectivism in cross-cultural training. They concluded that the development of the field of cross-cultural training over the past fifty years showed an encouraging sign of evolution of more theoretically meaningful training methods and tools. It could be expected that more theory-based training methods and material are likely to be developed in the future. In this chapter, a framework is presented for the development of intercultural training programs that includes not only culture theories but also other theoretical ideas thus extending the field.

Landis and Bhawuk (Reference Landis, Bhawuk, Landis, Bennett and Bennett2004) proposed a nested framework of testable models of intercultural training and learning. The models were based on a structure first proposed by Landis, Brislin, and Brandt (Reference Brislin, Landis, Brandt, Landis and Brislin1983). The first building block of their framework included such variables as intention to learn new cultural behavior, social support, host reinforcement, and spouse and family support to the sojourner. They posited that behavioral rehearsal would often be needed in the intercultural context, because people are learning new behaviors while living in another culture, and acquisition of such behaviors would necessarily follow the social learning theory (Bandura, Reference Bandura1977). The acquisition of these new cultural behaviors would be moderated by social support as well as host reinforcement. If spouse and other family members as well as the expatriate community support the target person to acquire these new behaviors, the person is likely to do a better job of learning these behaviors. Similarly, if the host nationals the sojourner is working with support the acquisition of the new behaviors, and encourage the sojourner, then the learning process is likely to be more effective. And building on the psychological literature, they posited that behavioral intention would be the best predictor of intercultural behaviors. This model could be tested for a number of intercultural behaviors like learning foreign languages, learning gestures and body language, and so forth.

Landis and Bhawuk (Reference Landis, Bhawuk, Landis, Bennett and Bennett2004) presented other models as the antecedents to the above model. For example, intercultural effectiveness is often evaluated based on how well the tasks get done, and so they argued that in most intercultural interactions tasks take central stage, and centrality of goal is likely to have direct impact on behavioral intentions and ultimately intercultural behaviors. Interestingly, the role of task completion in the intercultural context has not been tested in the literature, and thus does provide an opportunity to build and test theory. Another antecedent of intercultural behavioral intention would be affect (Landis & Bhawuk, Reference Landis, Bhawuk, Landis, Bennett and Bennett2004). Affect, it will be recalled, plays an important role in Triandis’s model of social behavior. Affect could vary along two dimensions. First, people could be different on their predisposition to change emotionally; some are ready to change versus others needing much more convincing or cajoling. Second, some people are more apt to express their emotions than others. Both of these affect-related aspects have implications for overseas adjustment, and people need to become self-aware, and then learn to adapt their style to be effective in another culture. For example, in some cultures emotion is not to be expressed publicly, whereas in others it is not honest to hide one’s emotion.

Of the two other models that Landis and Bhawuk (Reference Landis, Bhawuk, Landis, Bennett and Bennett2004) presented in their framework, one linked intercultural sensitivity, social categorization, behavioral disposition, and intercultural behaviors, whereas the other posited that intercultural behavior would be a function of perceived differences in subjective culture (Triandis, Reference Triandis1972), the greater the cultural distance (an important variable in Gudykunst’s theoretical model), the stronger the affective reaction. They suggested that individuals would seek information only up to the point where more stress becomes a deterrent for information seeking. They proposed that testing each of the models would require many experiments, and each of the studies could be viewed as a crucial experiment (Platt, Reference Platt1964) needed to build a theory of intercultural behavior. Integrating these five models, a general model of intercultural behavior process with its many antecedents is derived. Thus, they presented models testable through smaller studies, and also in its totality through a program of research. By testing these five models, and linking them together, the larger framework could be tested. In 2015 Warnick & Landis suggested that each model could have specific neural substrates that are activated by memories and current external environments. If validated by careful experiments, these suggestions could provide an explanation as to why some individuals seem completely impervious to changing behaviors, attitudes, and cognitions in an intercultural setting.

Landis and Bhawuk (Reference Landis, Bhawuk, Landis, Bennett and Bennett2004) noted that intercultural training researchers have been concerned with the development of the best training approach for most of the past fifty years, as much as they have been concerned about the evaluation of the effectiveness of intercultural training programs. They recommended that the discipline needed to boldly start building bridges between associated research disciplines. Following their recommendation, Bhawuk, Landis, and Lo (Reference Bhawuk, Landis, Lo, Sam and Berry2006) took the first step toward such a theoretical bridge-building, and attempted to synthesize the literature on intercultural training and acculturation. They attempted to integrate Berry's (Reference Berry and Brislin1990) four-part typology into a theoretical framework developed by Landis and Bhawuk (Reference Landis, Bhawuk, Landis, Bennett and Bennett2004), which seemed to open new avenues toward synthesizing these two disciplines. They also explored how different training tools could be used effectively to train people who are using different acculturating strategies. For example, they noted that it is reasonable to treat those who are using the integration strategy differently from those who are using the marginalization, separation, or assimilation strategies. This approach should also serve to bridge intercultural training and other research disciplines like sojourner adaptation, stress management techniques, and learning theories.

Bhawuk, Landis, and Lo (Reference Bhawuk, Landis, Lo, Sam and Berry2006) also noted various applications of individualism and collectivism in intercultural training, and suggested that perhaps acculturation literature should also take advantage of this theory more rigorously, which would further help bridge the two disciplines through a common theoretical foundation. They also attempted to synthesize intercultural sensitivity and acculturation literature by showing commonality between Bhawuk and Brislin’s (Reference Bhawuk and Brislin1992) approach to intercultural sensitivity, and Bennett’s (Reference Bennett1986) Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (see also Hammer, Bennett, & Wiseman, Reference Hammer, Bennett and Wiseman2003). In this chapter, some of these ideas are further explored in the context of developing the content of intercultural training programs. To do this a theoretical framework is developed, which is discussed in detail below. Prior to that development we will describe in more detail the major theoretical frameworks that have been used, starting with Triandis’s two equations predicting social behavior.

Triandis (Reference Triandis1977) presented two equations that specified the relations between a number of variables and the probability of a behavior occurring. The first regression equation predicted the probability the behavior would occur as an additive function of the level of habitually performing the behavior plus the intention to do the behavior multiplied by facilitating conditions. Both habit and intentions are multiplied by regression weights that are individually determined and indicate how important that variable is to the person.

Both habit and facilitating conditions are theoretically observable, but intentions are not and are usually obtained by some sort of self-report on a questionnaire or survey. So Triandis (Reference Triandis1977) then developed the second equation, which, like the first, was regression in construction. Here intention was seen to be an additive function of the affect (feeling) response to the persons who are the target of the behavior, the social appropriateness of the behavior (the norms and roles of the actor’s society), and, lastly, the perceived consequences of the behavior. Triandis attached individual difference regression weights to each component. These weights reflect the importance of each component to the actor for that specific behavior.

Triandis (Reference Triandis1977) then, in an adaptation of attribution theory, reasoned that the task of a person interacting with an individual from another culture was to develop a set of beliefs that came to be called “isomorphic attributions.” In other words, the attributions of the actor about the “other” should mirror those that the “other” would make about themselves. Put another way, the two equations from person 1 should essentially be the same as those from person 2. Any training, based on the above formulations, must then encourage the trainee to assess the other’s intention, affect, their culture’s norms and roles with respect to the interaction, and the likely outcomes (positive or negative) of the interaction. For that, Triandis and his colleagues came up with the idea of the culture assimilator. The concept of the simulator was explicitly based on the two equations that are described above. A more-fine-grained discussion is provided in Chapter 2.

While Triandis came from a background in experimental and social psychology, Gudykunst’s perspective was that of a scholar of communication behavior. He posits two antecedent variables to intercultural adaptation: anxiety and uncertainty reduction (Gudykunst, Reference Gudykunst1985). And these variables are in turn affected by three other groups: social contact, perceived similarity, and cultural knowledge. In such a structure, it is possible to generate hypotheses about any number of relations. In fact, there were at least fifty such predictions (Gao & Gudykunst, Reference Gao and Gudykunst1990; Gudykunst & Sudweeks, Reference Gudykunst, Sudweeks, Gudykunst and Kim1992). And most of the predictors turned out to have significant positive weights. It should be obvious that Gudykunst’s model is at a level of abstraction above that of Triandis, although it does adopt some of the latter’s terminology. The use of anxiety (or intercultural anxiety) came from the affect variable in Triandis, while uncertainty reduction came from Hofstede’s five factor description of culture dimensions. All of the variables were measured using self-report paper and pencil surveys. In his chapter in the 2nd Edition of this Handbook (Gudykunst, Guzley, & Hammer, Reference Gudykunst, Guzley, Hammer, Landis and Bhagat1996), he outlined a training design that more or less followed the AUM model, but which focused heavily on individualism and collectivism, another one of the Hofstede dimensions. A reasonable person could conclude that the case has yet to be made that the AUM model can be tested with the rigor that would be desired.

Berry (Reference Berry and Padilla1980, Reference Berry1989, Reference Berry1997, Reference Berry2005) developed a model that has found favor as a picture of the process of acculturation. It could be argued that well-developed training approaches can only enhance the ability of migrants to thrive within their country of settlement and thus it is appropriate to discuss this model. Ten years ago, Ward (Reference Ward2008) found that over 800 studies had cited Berry’s work, most of them positively. There have been, to be sure, writers who have been critical (e.g., Boski, Reference Boski2008; Chirkov, Reference Chirkov2009; Rudmin, Reference Rudmin2009). But, as Warnick and Landis (Reference Warnick and Landis2015) noted, its robustness has been such that many empirical studies have been spawned from it.

Berry suggested that a migrant desiring to settle in a new culture faces two major decisions: how much to retain of their origin culture and, at the same time, how much of the settlement culture to accept and retain. If we segregate each decision into two parts, we have four “acculturation strategies”: integration when both the origin and settlement cultures are retain (i.e., neither is rejected), separation when the settlement culture is rejected in favor of the heritage culture, assimilation when the heritage culture is rejected in favor of the settlement culture, and marginalization, with both cultures being rejected. An interesting fallout from Berry’s four-cell model of migrant individual decision-making was to link it to governmental actions. Thus, integration is linked to multiculturalism, separation to segregation, assimilation to melting pot, and marginalization to exclusion.

The nested models of Landis and Bhawuk alluded to earlier are too extensive to go into now. But, in an attempt to suggest neural substrates for each model, Warnick and Landis (Reference Warnick and Landis2015) suggested brain areas that could underlay each function. Thus, the Caudate region has been found to be associated with behavioral rehearsal. Behavior intention seems to be related to activity in the Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, the Dorslateral prefrontal cortex, and so on. Their attempt, of course, remains theoretical and must wait upon future empirical studies. But we see the relationship of intercultural interactions and neural functioning to be an important and critical pathway for future research. This follows from the traditional levels of micro, meso, and macro theory, where most social psychology approaches (and intercultural interaction fits here) reside somewhere in the meso level (Triandis is clearly, like Hull, at the micro level). In order to encompass the direction suggested by Warnick and Landis, a new category reflecting neural functioning has to be created. We suggest the label “nano” level. However, except in Chapter 20, this interesting approach is not deeply explored in this book.

A Theoretical Framework for the Development of Intercultural Training Programs

It is possible to synthesize various elements of the intercultural training literature in a theoretical framework that highlights the tension between culture-specific and culture-general training programs, yet shows the value in integrating them to effectively train sojourners for international assignments (Bhawuk, 2009, 2018c). This framework builds on a typology of intercultural training that focuses on three dimensions: degree of involvement of trainees, role of instructor, and the content of training – culture-specific or culture-general (Bhawuk, Reference Bhawuk1998). For example, experiential training programs are student centered, whereas lectures are instructor led, and each has its own merits and disadvantages. When crossed with whether the training is culture specific, focusing on a particular culture, or culture general, focusing on general principles of intercultural adaptation processes, the typology is enriched, and provides a framework for evaluating intercultural training programs.

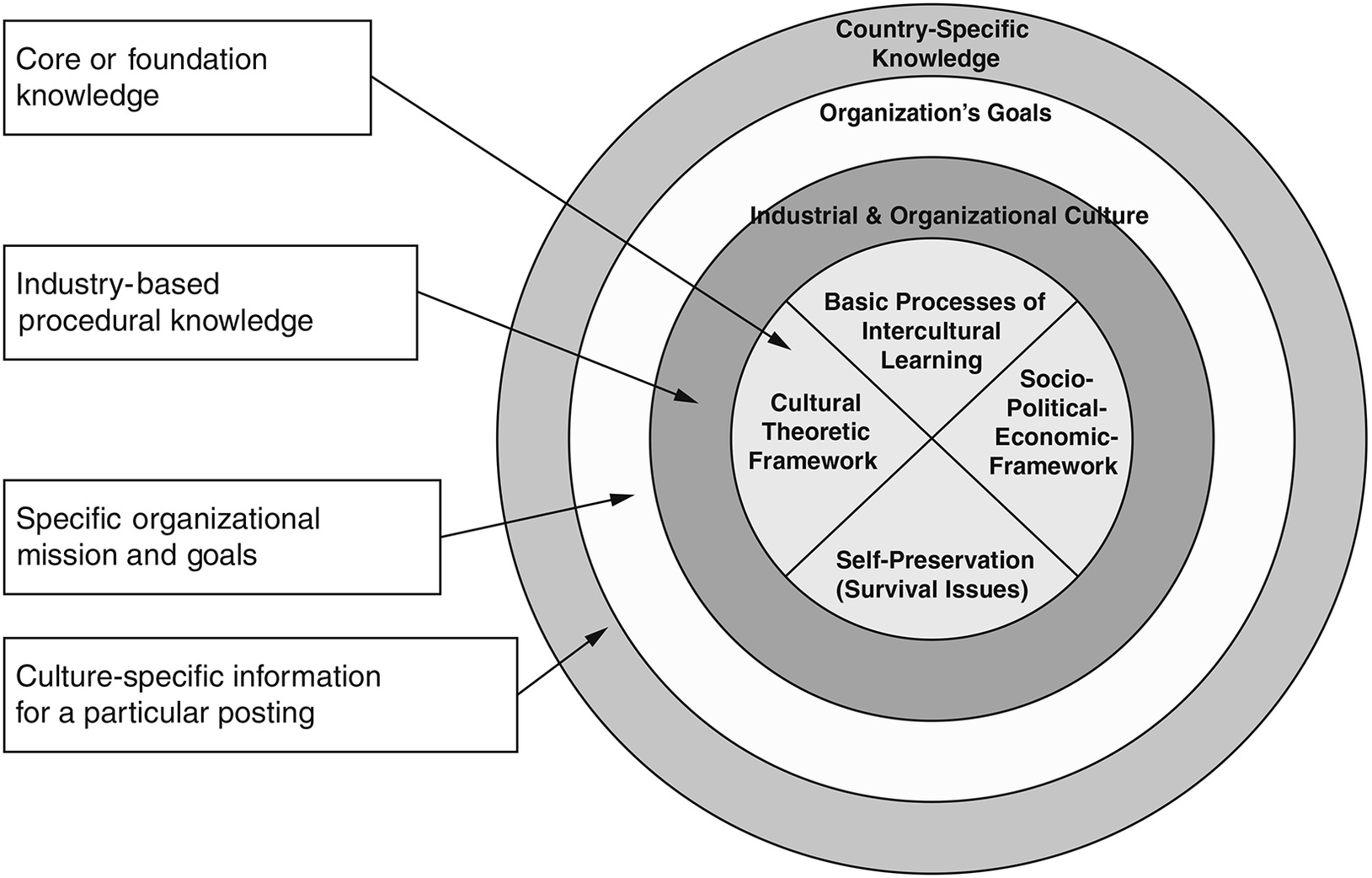

This framework includes three types of culture-specific knowledge: (1) national culture-related material, (2) industry-specific knowledge, and (3) organizational culture, strategies, and structures. These three are the outer layers of the knowledge needed by sojourners to interact effectively in the host culture. There are four types of culture-general knowledge that constitute the core of the framework: (1) personal safety-related knowledge, (2) basic principles of intercultural learning, (3) culture theories (see Chapter 4 in this volume), and (4) socio-political and economic frameworks that help understand systems across countries. These four elements constitute the foundational knowledge necessary to be effective in international assignments, and as they are grounded in theory they constitute associative rather than declarative knowledge. Every sojourner needs to learn these to be effective.

The basic argument forwarded by the framework is that, when we enter a culture, we face culture-specific issues in our daily lives. The knowledge of general principles and theories and the mission of the organization guide us in the daily interactions that take place in the ecology of a particular culture. The culture-specific and culture-general areas presented in the framework represent areas of research, theory, and practice from which the content of intercultural training can be derived.

There is much culture-specific information that expatriates need to operate effectively in a particular culture. These include norms of the target culture related to various kinds of behavioral settings for both public and private domains. Adaptation to greetings, eating different foods and drinks, modes of transportation, climate, living conditions, schools for children, grocery and other shopping, health, social amenities, media, entertainment, and so forth exacts much personal and psychological resource from the sojourner. And adjustment to work-related issues bring their own stress. Adapting to host culture requires more than cognitive knowledge, and entails behavior modification as well as emotional adjustment. Sojourners need much support from the host nationals and their organizations in order to integrate effectively into the local community.

Next to the specific culture in which a sojourner will be working is the industry in which the sojourner is likely to have some experience – and which has its own unique culture. For example, nurses and doctors are in the health industry, teachers and students are in the education industry, and managers work in various industries (e.g., information technology, manufacturing, petroleum, construction, airlines, service, and so forth). Each industry is different, not only because the external environment presents differently to it, but also because each industry develops its own symbols and rituals since it serves different clientele with different products and services. For example, the airline industry works differently from the petroleum industry Each of these industry has its own culture that has some common features across national cultures, but still sojourners have to adapt to some differences between national and industry cultures.

There are specific intercultural skills that the expatriates must acquire and use in the behavioral settings pertinent to their industry and organization. Organizational cultures are nested in the industrial culture but are also shaped by their national cultures, especially in human processes and the management of human resources. It is often assumed that sojourners understand the culture of the organization, and if they are going from the headquarters of the organization they may even be viewed as experts on organizational routines and procedures. However, there are nuances of the organization in the target culture that are different from those in the host nation. The mission and goals of the organization represent higher-level outcomes that the organization desires to achieve in its operations abroad, and these put intercultural demands on the expatriates. Clearly, effective accomplishment of organizational objectives will require more-complex and adept intercultural skills.

Researchers and practitioners alike, in their zeal of preparing people to be effective in their sojourn, often neglect the basic issues of survival, or assume that the sojourners will take care of such issues themselves (Leki, 2008). This is a mistake, and all training programs must stress the need for self-preservation, which not only is unique to an individual, but also has some cultural underpinnings depending on who the sojourner is and where he or she is going to live. For example, there are likely gender differences that need to be addressed, as women have to deal with many more issues when moving from one culture to another than men have to do. Clearly, there are many aspects of survival that expatriates need to worry about, and without taking care of these issues they simply cannot be effective in their work or social interactions. This has become a particularly important issue in view of the increased terrorist activities that the world has seen since 2001.

When we live in our own culture, we know how to go about doing various activities, and we also know where not to go and when. This is not obvious when we live in another culture. For example, taking a taxi from the airport to the city may be a simple task in one culture, but not so safe in another culture. Most big airports in India provide a prepaid taxi service to ensure the safety of passengers. I know of a returning young Indian who got robbed by a taxi driver simply because he had ignored the safety procedure and taken a non-registered taxi. Often local people know which activities should not be undertaken or which parts of the city should be avoided at certain times of the day or night. Sojourners need to acquire this information and pay special attention to avoid difficult situations.

Sometimes sojourners get carried away when they have lived in a new culture and feel comfortable. This may sound like being over cautious, but it is better to be over cautious while living abroad. For example, having traveled to the USA many times, and having lived there for two years, early in my sojourn Bhawuk found myself in a precarious situation waiting for a bus in down town Los Angeles at 1:00 am while returning from Disneyland with my wife and two little children. It was a scary situation with a police patrol car going around every few minutes and many shady-looking people sauntering along the street. Bhawuk called my cultural informant, who was alarmed to learn my situation but was not able to come and fetch us because he lived too far away from there. He calmly gave directions about how to go to a safer street where a five star hotel was located. I had unwittingly put myself and my family in a difficult situation, which could easily have been avoided.

When we are living abroad, we are often so different that we do not quite fit into the social settings. People recognize us as a foreigner, and we become self-conscious. Also, when we are in a completely new setting, we have to learn about the place and people, and it is normal to experience cognitive load in such situations as we experience much ambiguity. This is enough to trigger a sense of insecurity, and people often complain about experiencing moderate levels of anxiety. It is not unusual to feel that people of the host culture are staring at us. One does get over it slowly over time, if things go right. But if the assignment is only for a short duration, and one has to be in social settings, then it is important to become aware of one’s own discomfort, and to learn to perform one’s tasks despite the nagging feeling of insecurity. It should be noted that it is harder for military personnel not to stick out when they are abroad because they are not only a foreigner, but also a person in military uniform, distinct from the locals. And if they are in a hostile environment, say US soldiers and civilians in Iraq or Afghanistan, then safety must not be taken for granted, and all precautions must be observed.

When we live in our own culture, we also have our emotional support group that is often take for granted because the members of this group are there for us when we need them. When we are in another culture, we have no access to this support group, and thus we need to develop one. It is difficult to talk about life circumstances that are personal in nature and cause stress. For example, an illness or death in the family, our own or a family member’s marital problems, and so forth take a lot of energy, and, when we are away from home, thinking about these matters can be quite debilitating.

Most often we are not prepared to deal with our own death or the death of close family members. Talking about these matters is hard, yet accidents do happen, and people die unexpectedly. When we are in our own culture, we deal with them as they arise. However, when we are abroad, distance separates us from family, and we may regret not knowing what a dear one had wished for us to do. Before going abroad for a long assignment, it is necessary to talk about these matters with one’s family and close friends and relatives, and prepare them to some degree for the unforeseen circumstances. Leaving instructions about how one should be cremated or dealt with if incapacitated is necessary. Having a will and leaving a power of attorney for somebody to take care of our financial and other personal matters is also helpful. Preparing for these emotional issues provides extra energy because one has fewer things to worry about when living abroad.

It is also important to think about the future, and the implications for oneself and other family members, should one decide to marry someone from another culture while living abroad. It is not unusual for people to fall in love and develop a serious relationship with someone while living abroad, and it is good to think about such matters before they arise. Doing so helps with preparedness by reducing the stress arising from personal, emotional, and existential self-preservation.

Safety and survival issues have not received much attention in intercultural research beyond examining the nature of culture shock and its consequences. Expatriates are expected to learn about safety matters themselves, and not much time is spent in counseling them to prepare for the target culture. For example, We personally know of people who took international assignments thinking that their troubled marriage would heal in an exotic place. Unfortunately, the new place adds more stress and invariably makes things worse, often leading to a break-up of the marriage. We cannot make progress unless organizations start providing training on this topic. Some guidance is available about how to prepare people on matters of personal safety, and an inventory is available that people can use to learn about their own safety needs while planning to travel abroad. This material and practical tips on how to prepare for personal safety when living abroad has been found to be useful in the training programs provided by the US State Department (Leki, 2008).

Economic circumstances have profound effects on the work and social life of people, and personal income constrains an individual’s choice of activities. Personal wealth also affects a person’s perspectives on many social issues. Individuals from economically advanced countries generally enjoy greater levels of cosmopolitanism and participation in the global economy, whereas those from economically developing countries tend to have a life concerned with more immediate issues of survival. Thus, globalization has different meanings for economically developed and developing countries. By categorizing countries as either developed or developing nations, it is possible to identify the distinct approaches people use to make decisions in these societies. This framework is useful in understanding differences resulting from variations in economic systems between developed and developing countries over and above their cultural dissimilarities. A discussion of such economic differences allows for building synergy across cultural differences, since differences emerging from economic factors are presumed to be workable, and less likely to be the source of value-based conflicts (Bhawuk, Reference Bhawuk2009b).

Governments base their business policies on the overall economic condition of the country. National policies for stimulating economic development are grounded in the tenets of development economics. As nations progress through the various stages of economic development, national strategies, priorities, and values shift to meet the demands of a more affluent population. Policies and beliefs surrounding macroeconomic issues such as comparative advantages, role of government, and role of business in society change with growing national wealth. Expectations of businesses also evolve as an economy develops, and change often occurs across both business and social categories.

Businesses within a market compete against each other through competitive advantages, but countries compete against each other through comparative advantages. Production capabilities compare differently across borders, as each country has a different mix of talents and costs associated with its production factors of labor, raw materials, and infrastructure. Developing countries tend to specialize in low-cost labor, while developed countries tend to specialize in capital-intensive production. International managers must recognize the specific strengths and weaknesses of each country and adjust their decisions appropriately.

Businesses in different countries also share different relationships with their governments. Developing economies often follow more-centralized planning, allowing a greater role for governments in shaping business policies. During the initial stages of economic development, guidance from the government has historically led to greater economic growth, as seen in the success of Japan, Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan. Organizations operating in foreign countries must recognize the political imperatives of each nation and adequately address them in their business strategies. Often political imperatives may encourage governments to actively intervene to protect local firms against foreign competition. Rigidly adhering to an inappropriate strategy under such conditions would invariably lead to the failure of a multinational company.

As businesses commit more resources to a specific country, they inevitably establish stronger ties to the community. Gaining acceptance from the local community can be considered a benchmark for business success, but the nature of the relationship must constantly be evaluated against the expectations for businesses’ role in society. Social and cultural expectations strongly guide expected corporate responsibilities, but economic factors also play a considerable role. Literature on cultural complexity shows that developed countries tend to be more complex than the developing countries and exhibit more individualistic tendencies. Some may argue that developed countries are more democratic and open to progressive social change, but a better statement is that economic development leads to inevitable conflicts between a society’s traditional values and introduced beliefs of the international community.

Economic forces also shape the intrinsic motivation of people. Financial incentives are found to be more important in the developing economies than economically more advanced economies. Similarly, happiness or subjective well-being is a function of income in the developing countries but not in the economically developed countries. Further, developed countries are found to be post materialist in that people expect their national governments to focus on providing more opportunity for individual participation in government decisions and defending freedom of speech. On the other hand, the developing countries are found to be materialist in that people in these countries expected their national government to focus on keeping order within the country and keeping prices at minimum (see Chapter 4 in this volume).

An individual’s awareness and acceptance of the global community is also influenced by economic circumstances. Workers from nations with minimal exposure to globalization are likely to view convergence of business practices with contempt or suspicion. Expatriates imposing their home countries’ approaches on local communities may be viewed against the historical backdrop of colonization. The recent activism against globalization is a symptom of this mistrust. Support for the World Trade Organization can often be divided between developing and developed countries. Few governments from developed countries take active stances against globalization, but the majority of government that openly dissent with globalization initiatives are from developing countries.

The economic framework captures some aspects that are important for sojourners in their adaptation to the host culture, which are not covered by culture theories like individualism and collectivism, and thus offers to be valuable for intercultural training. This framework can be further enriched by adding political and social dimensions so that differences resulting from religion, form of government, and other socio-political institutions and practices can also be captured. By using developing and developed countries as prototypes, socio-political-economic differences can be effectively discussed in cross-cultural training programs (Bhawuk, Reference Bhawuk2009b).

Traditionally, intercultural training programs have been more focused on the culture-specific training with the objective of orienting people to the target culture. For this reason many intercultural training programs remain at the level of dos and don’ts, neither of which facilitates acquisition of meta-cognition or learning-how-to-learn. A balance of culture-specific and culture-general training programs enhances the effectiveness of intercultural learning. Once sojourners have obtained the foundational knowledge and awareness, they are then able to synthesize the specific skills that support the overall objectives of the organizations in the industry in which they operate. With this preparation, they are finally able to deeply appreciate specific information about the culture in which they work. By first learning the foundational knowledge and culture-general skills, expatriates will be better able to assimilate cultural-specific training when it occurs, and much of it is likely to occur on site while living in another culture (see Figure 1.1).

The debate between educators as to which format, culture specific or culture general, should be used for intercultural training has been going on for more than fifty years. Some researchers support culture-general training, arguing that individuals learn to see the differing value structures that may be found in different cultures when they receive insight into their own culture. The idea is that self-awareness of their own culture may result in greater understanding of other cultures’ values. Other researchers have argued for culture-specific training suggesting that cross-cultural training must not only fulfill the trainee’s needs for fact and language, but also influence the affective behavior of the trainee so that effective communication can take place in the target culture.

There are many topics that are relevant for effectiveness in cross-cultural interactions that are not specific to any culture. For example, “people are ethnocentric in every culture” and “attributions made by hosts are usually different” are two generalizations that work across culture. Sojourners need to see a positive aspect in every situation, find new recreational activities in the host culture, avoid over-dependence on the expatriate community, and so forth: such insights are found to work for most sojourners irrespective of their location. Other general skills include: Learn to differentiate what is personal from what is national (e.g., an Australian may have to take the brunt of criticism for the national policy of Australia), take the lead in starting a conversation with hosts to learn more about their culture, live with ambiguity and suspend judgment, and transcend differences in attitudes and values. Since these are skills that are needed to be effective in many cross-cultural situations, they could be called meta-skills of cross-cultural interactions. Such meta-skills also constitute aspects of culture-general training.

There are problems when using either the culture-general or the culture-specific training exclusively. Culture-general training requires more time because it involves increasing the awareness of the trainees. Also, the trainees have no idea about which behaviors are rewarded and which warrant punishment in the host culture. As for the culture-specific training, the generalizations given during training can leave the trainee with preconceived notions that may not be accurate. The list of dos and don’ts are easy to forget when the trainee does not understand the other culture. Comparison of culture-specific and culture-general training material has shown that each type of training is more effective than the other on some criteria, suggesting that using a combination of training may be a better strategy – which has also been supported in research.

Basic Processes of Intercultural Learning

A Model of Cross-Cultural Expertise Development

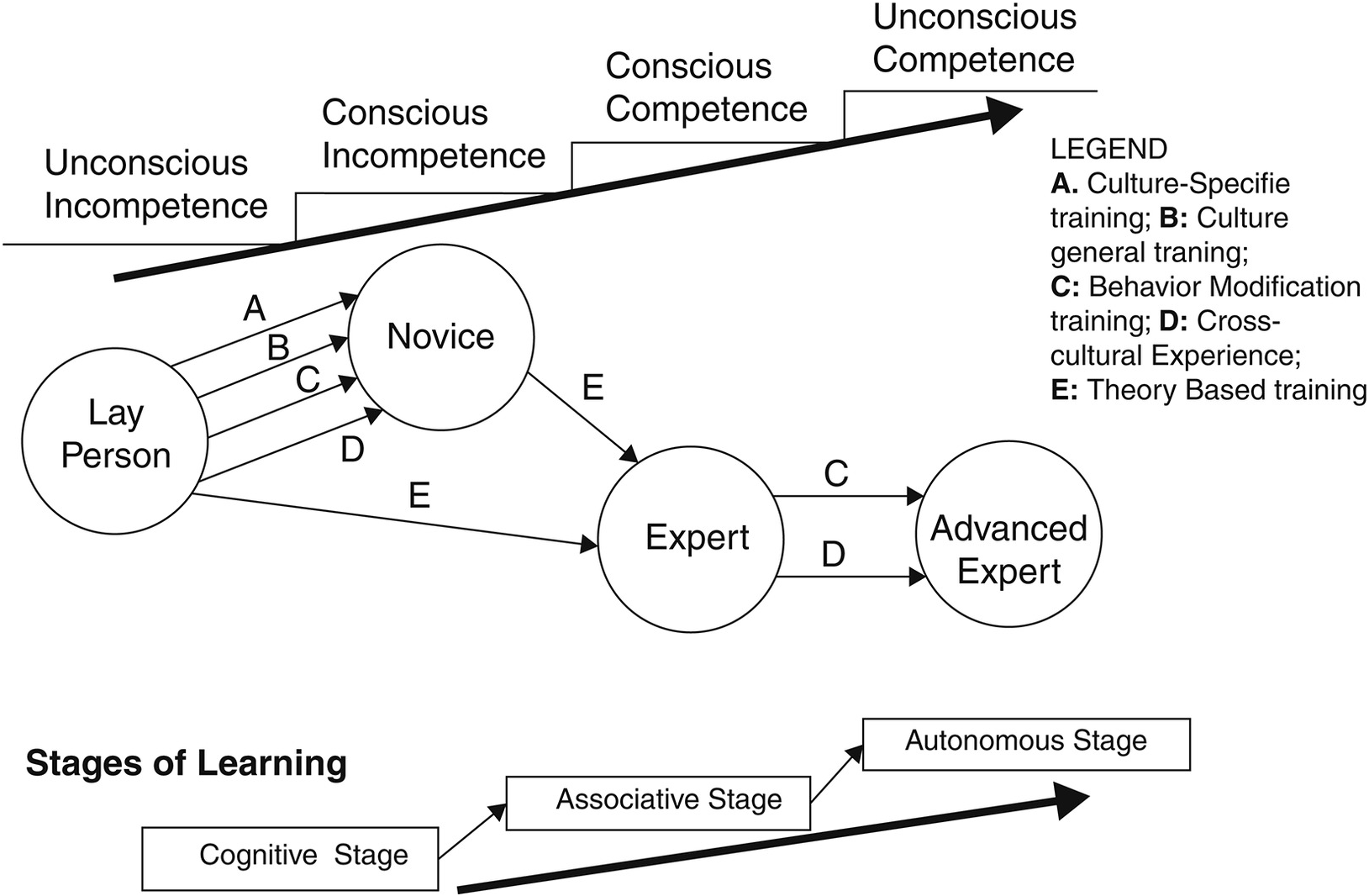

Building on the notion that theories have a role in the development of expertise, Bhawuk (Reference Bhawuk1998) proposed a model of intercultural expertise development (see Figure1.2). A “lay person” is defined as one who has no knowledge of another culture, an ideal type for all practical purposes, considering that even the Sherpas in the remote Nepalese mountains or the pygmies in Africa have been exposed to people from other cultures. There is some evidence that people who have spent two or more years in another culture develop cross-cultural sensitivity through their intercultural interactions, even in the absence of any formal training (Bhawuk & Brislin, Reference Bhawuk and Brislin1992). It is proposed that people with extended intercultural experience, or those who have gone through a formal intercultural training program (e.g., a culture-specific orientation) that discusses differences between two cultures, will develop some degree of intercultural expertise and are labeled “novices.” In other words, “novices” are people with some intercultural skills or expertise, usually for a culture other than their own. These are people who are still in the first stage of learning (e.g., the cognitive or declarative stage, Anderson, Reference Anderson2000). These people are likely to explain a cultural difference in terms of behavioral observations such as “One does not say ‘No’ directly in Japan,” “Nepalese men do not do household chores,” and so forth, which often leads to a dos and don’ts list.

Figure 1.2 A model of cross-cultural expertise development.

“Experts” are novices who have acquired the knowledge of culture theories that are relevant to a large number of behaviors so that they can organize cognitions about cultural differences more meaningfully around a theory (e.g., the way experts use Newton’s second law of motion to classify physics problems). These are the people who are at the second stage of learning (e.g., the associative or proceduralization stage, Anderson, Reference Anderson2000). It is proposed that people can arrive at this stage by going through a theory-based intercultural training program.

“Advanced experts” are experts who not only have the knowledge of the theory, but also have had the amount of practice needed to perform the relevant tasks automatically. These are the people who are at the third stage of learning (i.e., the autonomous stage, Anderson, Reference Anderson2000). Since behavior modification training allows people to learn new behaviors by observing models and then practicing the target behaviors, a behavior modeling training following a theory-based training, will enable “experts” to become “advanced experts.” Thus, the model of intercultural expertise development posits that intercultural training using culture theory will make a person an expert, whereas training that does not use theory will only result in novices. And to be an advanced expert one needs to go through behavioral training to practice different behaviors so that the behaviors become habitual. Figure 1.2 is a diagrammatic representation of this model, and it also shows the linkages between stages of learning and stages of intercultural expertise development.

Levels of Competence

Extending the work of Howell (Reference Howell1982) to cross-cultural communication and training, Bhawuk (Reference Bhawuk1995, Reference Bhawuk1998) suggested that there are four levels of cross-cultural competence: unconscious incompetence, conscious incompetence, conscious competence, and unconscious competence. Unconscious incompetence refers to the situation when one misinterprets other people’s behavior but is not even aware of it; this is the situation when a sojourner is making incorrect attributions, usually based on his or her own cultural framework. When a person is at this level of competence, things do not work out the way one expects and one is not sure why things are not working. This characterizes the situation when a sojourner is experiencing culture shock or culture fatigue (Oberg, Reference Oberg1960). A person at this level of competence is a “lay person” in the model presented earlier (see Figure 1.2).

Conscious incompetence refers to the situation when the sojourner has become aware of his or her failure to behave correctly, but is unable to make correct attributions since he or she lacks the right knowledge. The sojourner is learning by trial and error. This level of competence is exemplified by a tennis player who tries to improve his game without coaching or study, by simply playing more. The sojourner who is trying to figure out cultural differences through direct experience, or non-theory based training programs, fits the description of this level of competence and is called a “novice” in the model.

Conscious competence is the third level and the crucial difference between this and the previous level is that the person at this level communicates with understanding. The person understands why something works or does not work (i.e., he understands the covert principles and theories behind overt behaviors). A person at this level of competence is called an “expert” in the model.

It is suggested that level two in the competency hierarchy is mechanical-analytical in that a behavior that is less effective than another is dropped, whereas level three is thoughtful-analytical in that not only is an effective behavior selected but also an explanation of why a behavior is effective or ineffective becomes available (Howell, Reference Howell1982). In the cross-cultural setting, at this level a sojourner is still not naturally proficient in his or her interactions with the hosts and has to make an effort to behave in the culturally appropriate way. For example, people who do not use “please” or “thank you” in their own culture, and are at the third level of competence, have to remind themselves and make a conscious effort to use these words in social interactions in a culture where they are expected to use them.

When a person receives enough practice then a behavior becomes part of one’s habit structure and one does not need to make an effort to behave in a culturally appropriate way; one has become so acculturated that one can almost pass as a native. This is the fourth and the highest stage of competence, unconscious competence, and corresponds to the “advanced expert” in the model. At this level, although the person fully understands the reasons for behaving in a certain way in another culture, neither mechanical nor thoughtful analysis is required and a person responds “correctly” automatically (i.e., the response is habitual).

Cognitive Stages of Expertise Development

Anderson (Reference Anderson2000) described how people develop expertise. According to him, skill learning occurs in three steps. The first step is a cognitive stage, in which a description of the procedure is learned. In this stage, the names and definitions of concepts and key entities are committed to memory. Therefore, knowledge is “declarative,” and people have to make an effort to recall and apply what they have learned. Typically, learners rehearse the facts in first performing the task. For example, an individualist (e.g., an American manager) who is new in a collectivist culture (e.g., Japan) and faces an interpersonal situation in which he or she wants to disagree or reject an offer, idea, or solution would recall the fact that people in Japan prefer not to be direct and forthright. but instead use many euphemisms for saying “No.” The knowledge of this information is declarative and in this situation the manager would rehearse this fact as he or she interacts with the Japanese. A natural feeling at the end of the interaction may be “Boy, that was difficult,” “That was not bad,” “I hope it is easier the next time,” and so forth, depending on one’s feeling of success or failure with the interaction. In this stage of learning, the person is aware of the entire process of recalling knowledge and applying it to the situation

The second stage is called the associative stage, in which people convert their declarative knowledge of a domain into a more efficient procedural representation. Starting with the cognitive stage, learners begin to detect many of their mistakes in performing a task or skill, and eliminate some of these mistakes. Further, with practice they remember the elements of the procedure and their sequence. As learners get into the associative stage, they no longer have to rehearse the knowledge before they can apply it, and they follow a procedure that they know leads to a successful result. In the cross-cultural context described above, the American manager would interact with the Japanese worker without a need to recall or rehearse the fact that the Japanese do not say “No” directly. The manager will be able to smoothly get into the discussion, find a suitable excuse to disagree, and use a proper expression of negation so that the worker does not lose his or her face. Thus, in this stage people learn the steps of performing a task, and while performing it follow each step in the proper sequence. This is referred to as “proceduralization.”

It is suggested that sometimes the two forms of knowledge, declarative and procedural, can coexist; for example, a person speaking a foreign language fluently can also remember many rules of grammar. In the context of intercultural interaction, it is likely that both declarative and procedural knowledge will coexist since the sojourner needs to constantly keep the rules of the host culture in mind to contrast it with proper behavior in his or her own culture. Only in the extreme case of a person going “native” (i.e., a person assimilating completely in the host culture) is it likely that there will be a singular presence of procedural knowledge. Complete assimilation is reflected in the sojourner’s inability to explain why the hosts (or the person himself or herself) behave in a certain way, and the person is likely to say “That is the way to do it.”

The third stage, in which the skill becomes more and more habitual and automatic, develops through practice and is called the “autonomous stage.” People know the task so well that they can perform it very quickly without following each and every step. Speed and accuracy are the two characteristics of this stage; people perform the skills quickly and with few or no errors. In the scenario discussed earlier, when he or she is in this stage of expertise development, the American manager in Japan would be able to convey an equivalent of saying “No” very quickly and without making an error to upset the host. A Japanese worker is likely to think of this person as “so much like us,” “extremely polite,” and so forth. People who are in this stage are sophisticated users of knowledge in a particular domain (a particular culture in the case of intercultural interactions) and use broad principles to categorize and solve the problems of the domain.

It is suggested that there is no major difference between the associative and the autonomous stages, and that the autonomous stage can be considered an extension of the associative stage. In this stage, usually skills improve gradually, and since verbal mediation does not exist learners may be unable to verbalize knowledge completely. In effect, the autonomous stage refers to behaviors that have become habitual through extended practice. This stage is especially relevant to intercultural interactions since sojourners are driven by habits acquired in their own culture, and acquire behaviors suitable for the host culture slowly, stage by stage, from the cognitive to the associative to the autonomous stage. Often these new behaviors are opposite of the behaviors learned in one’s own culture. For example, the American manager in the example above has to stop being direct and forthright, something valued in the United States, and start being indirect and vague, something valued in Japan. As mentioned earlier, if the sojourners do not want to go “native” (i.e., become just like the host culture nationals), they would need to be proficient in interactions with the hosts, but at the same time also be able to verbalize knowledge about behaviors in the host culture so that they retain their home culture’s identity.

The development of expertise is reflected in how people (experts versus novices) solve problems. When experts and novices are asked to solve physics problems, specifically to find out the velocity of the freely sliding block at the end of an inclined plane, it is found that novices worked backward, step by step, starting by writing the formula to compute the unknown (the velocity), then writing the formula for another unknown in the first formula (acceleration), and so on, and then moving forward, computing each of the unknowns, until the solution is found (Anderson, Reference Anderson2000). On the other hand, experts solved the same problem in the opposite order, by using theories (e.g., Newton’s second law of motion) and computing directly what could be computed, and then moving on to finally solve the problem. The backward-reasoning method followed by the novices loads the working memory and can result in errors, whereas the forward-reasoning method followed by experts is superior in that it is more accurate as it does not load the working memory. To be able to use the forward-reasoning method, the user must be conversant with all the possible forward solutions and then be able to decide which one will be relevant to the problem at hand, and this requires a good deal of expertise.

In cross-cultural interactions, the forward-reasoning method is likely to be followed by experts, since it is possible to predict human behavior given the setting and other characteristics of the situation. In fact, a central premise of social learning theory (Bandura, Reference Bandura1977) is that people anticipate actions and their consequences (i.e., people can decide how they would behave in a situation based on their past observation and experience). In a cross-cultural situation, for example, knowing that collectivists are sensitive to the needs of their ingroups, to motivate the employees an expert may use the strategy of creating incentives that are useful to their ingroups. More research is needed to understand the differences in the strategies adopted by experts and novices. It makes intuitive sense to think that experts would use theories to guide their interactions in intercultural situation.

Disconfirmed Expectation and the Processes of Learning How-to-Learn

Disconfirmed expectation refers to situations where sojourners expect a certain behavior from the host nationals, but experience a different one. Simply stated, one’s expectations are not met or confirmed. Intercultural communication effectiveness can be enhanced if we prepare ourselves not to come to a hurried conclusion about the cause of hosts’ behavior when the hosts do not meet our expectations, since such a conclusion can lead to a negative stereotype. A negative stereotype may prejudice future interactions with hosts resulting in interpersonal problems. Disconfirmed expectancies underlie many situations where differences in work ethics, roles, learning styles, use of time and space, and so forth occur.

Frustrations associated with disconfirmed expectation are a part of a basic psychological process that is also found in primates. For example, in an experiment a monkey is shown spinach in a box a number of times, and is thus socialized to expect spinach in the box. Later when spinach is replaced by another item unknown to the monkey, the monkey is found to show frustration and anger when it opens the box and does not find the spinach, which it expected to see (Overmier, Reference Overmier2006). Thus, it is not surprising that we humans too are frustrated by disconfirmed expectations. Often service quality is compared to what we expect, and thus often a poor quality is nothing but an expression of a disconfirmed expectation. Of course, intercultural interactions are likely to be full of disconfirmed expectations, and if we are not to be shocked out of our wits, which is what culture shock (Ward, Bochner, & Furnham, Reference Ward, Bochner and Furnham2001) is, we have to learn to deal with disconfirmed expectations.

It is posited here that disconfirmed expectations offer an opportunity for us to learn. In fact, when our expectations are met, we are practicing behaviors that we already know, and such situations lead to mastery of such behaviors to the level of automaticity, allowing such behaviors to become habitual. But when we face a disconfirmed expectation, we have a choice of ignoring it as an aberration, similar to a poor service situation, or reflecting on the situation to see if there is something to be learned. In intercultural settings, there is often a cultural behavior to be learned when we face a disconfirmed expectation. But unlike the motivated self-learner, others find this opportunity frustrating. Thus, to the motivated sojourner or expatriate disconfirmed expectations offer what Vygotsky (Reference Vygotsky1978) called zone of proximal development where meaningful new learning takes place beyond the previous ability level of the learner. Below, disconfirmed expectation is synthesized in the learning-how-to-learn model (Hughes-Weiner, Reference Hughes-Weiner1986; Kolb, Reference Kolb1976).

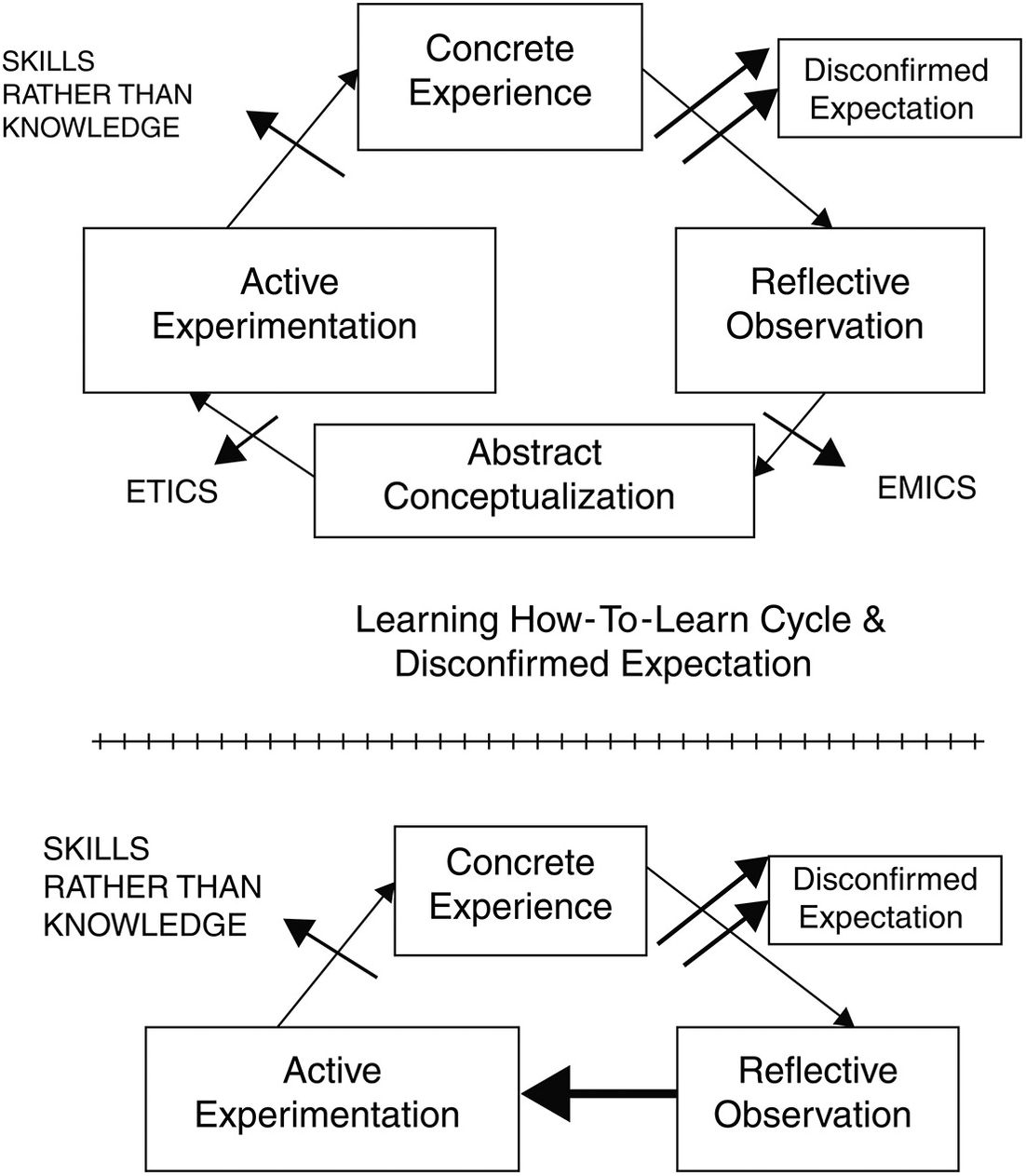

Building on Kolb’s (Reference Kolb1976) learning styles model, Hughes-Weiner (Reference Hughes-Weiner1986) presented a learning-how-to-learn model applicable to the field of intercultural communication and training. The basic idea presented by Hughes-Weiner is that, starting with concrete experience, a learner can move to reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation. Here Kolb and Hugh-Weiner’s ideas are further developed, synthesizing the concepts of disconfirmed expectation, emic (culture specific knowledge), and etic (culture general or universal knowledge) (see Figure 1.3). In an intercultural setting, we can stop at a concrete experience in which we do not understand the behavior of the host, and we can make an attribution that the actor is not a nice person (or even worse that he is a jerk or she is mean) or that the host culture is not a good culture (or even worse that this is a backward culture), and continue to act in the future the same way that we acted in such situations in the past. In other words, we happily move on, even if the hosts are not feeling good. Our behavior would support the notion that we are all ethnocentric (Triandis, Reference Triandis and Brislin1990), and we would continue to be ethnocentric. This state fits with the intercultural development model (Bennett, Reference Bennett1986), and the person is clearly not only ethnocentric but also uninterested in self growth.

Figure 1.3 Disconfirmed expectation and learning how to learn.

If we do reflective observation, we learn about cultural differences, and often some emic aspect of the host culture emerges. We also learn about our own culture, especially if the other cultural practices are drastically different from our own, which is mediated by cultural distance. Therefore, stopping at reflective observation leads to some personal intercultural growth. However, stopping here may end up into one learning many dos and don’ts about a particular culture. If we go beyond reflective observation, and develop abstract conceptualization, we acquire theoretical insights, which help us organize many experiences coherently into one category, and we can learn many such theoretical ideas. This leads to culture general understanding, and is a clear advancement from the earlier stage. We develop an understanding of etics, or universals, and understand emics as cultural representations of those etics. This helps us understand our own culture better in that we know why we do what we do. Also, it helps us internalize that our own cultural practices are not universals but emic reflections of some etics. Such internalization would weaken our natural ethnocentric cocoon and help us progress toward cultural relativism. In this phase, learning is supplemented by understanding. However, if we stop at this phase, we may have insights but our behavior may not show our understanding.

Active experimentation completes the cycle in that the learner is now testing theories and ideas learned. One is not only a “nice-talk-interculturalist” but an interculturalist who goes in the field, and tries out his or her learning. It is also plausible that people living in another culture for a long time move from reflective observation to active experimentation, simply bypassing the abstract conceptualization phase (see Figure 1.3). This is similar to behavioral modification training, except that the person is learning the behavior on the job and does not have much choice but to learn the behavior to be effective while he or she is living abroad. The pressures of adapting to a new environment and culture combined with the desire to be effective can lead one to master various behaviors in a new culture as a sojourner, without much abstract conceptualization. Thus, it is plausible that one can become an effective biculturalist (see Figure 1.3). However, due to the lack of abstract conceptualization, one may continue to cultivate some bitterness resulting from the frustration from the external pressure requiring one to adapt. Thus, we see that disconfirmed expectation and learning how to learn are meta-skills that intercultural training can impart to be effective in intercultural communication.

Isomorphic Attribution and Fundamental Attribution Error