Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Note on the Romanization of Chinese

- Introduction

- I FILM IN THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC

- II FILM IN TAIWAN AND HONG KONG

- 5 Remapping Taipei

- 6 The Ideology of Initiation

- 7 The Return of the Father

- 8 Border Crossing

- 9 Two Films from Hong Kong

- Chronologies

- Glossary

- Scholarly Works on Chinese Filmmaking in the 1980s

- Index

5 - Remapping Taipei

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 June 2012

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Note on the Romanization of Chinese

- Introduction

- I FILM IN THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC

- II FILM IN TAIWAN AND HONG KONG

- 5 Remapping Taipei

- 6 The Ideology of Initiation

- 7 The Return of the Father

- 8 Border Crossing

- 9 Two Films from Hong Kong

- Chronologies

- Glossary

- Scholarly Works on Chinese Filmmaking in the 1980s

- Index

Summary

The social totality is only sensed, as it were, from the outside. We will never see it as such. It can be tracked like a crime whose clues we accumulate, not knowing that we are ourselves parts and organs of this obscenely moving and stirring zoological monstrosity. But most often, in the modern itself, its vague and nascent concept begins to awaken with the knowledge function, very much like a book whose characters do not know that they are being read: the spectator alone knows that the lovers have missed each other by only five minutes, or that Iago has lied to the hero's uncle, giving him a view of the partners' motives that will never be corrected in this life, but that has disastrous consequences. These known misunderstandings bring into being a new kind of purely aesthetic emotion, which is not exactly pity and fear but for which “irony” is a used-up word whose original acceptation can only lend to conjecture. That it is purely aesthetic, however, means that it is conceivable only in conjunction with the work of art, cannot take place in real life, and has something to do with the omniscient author who is alone supposed to observe these disjoined occurrences, unknown to each other, save when the gaze of the author, rising over miniature rooftops, puts them back together and declares them to be the material of storytelling, or literature.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

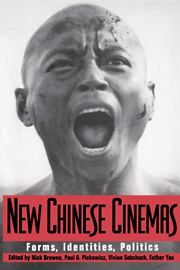

- New Chinese CinemasForms, Identities, Politics, pp. 117 - 150Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 1994

- 17

- Cited by