Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Note on the Romanization of Chinese

- Introduction

- I FILM IN THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC

- II FILM IN TAIWAN AND HONG KONG

- 5 Remapping Taipei

- 6 The Ideology of Initiation

- 7 The Return of the Father

- 8 Border Crossing

- 9 Two Films from Hong Kong

- Chronologies

- Glossary

- Scholarly Works on Chinese Filmmaking in the 1980s

- Index

8 - Border Crossing

Mainland China's Presence in Hong Kong Cinema

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 June 2012

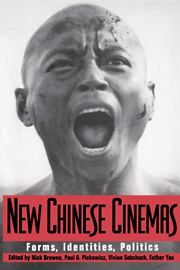

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Note on the Romanization of Chinese

- Introduction

- I FILM IN THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC

- II FILM IN TAIWAN AND HONG KONG

- 5 Remapping Taipei

- 6 The Ideology of Initiation

- 7 The Return of the Father

- 8 Border Crossing

- 9 Two Films from Hong Kong

- Chronologies

- Glossary

- Scholarly Works on Chinese Filmmaking in the 1980s

- Index

Summary

When they ask me for my nationality or ethnic identity, I can't respond with one word, since my “identity” now possesses multiple repertories. … I am a child of crisis and cultural syncretism.

Guillermo Gómez-Peña (1989)In many respects, Hong Kong appears to be an inappropriate place for postcolonial arguments. Since the early 1900s, residents of mainland China have left their own country for the British colony. Although the natives challenged colonial authority in the early years and are still negotiating with the government for better political representation, since the late 1970s, many of them have also become compliant. One of the most impressive capitalist enclaves in Asia, Hong Kong has an expanding middle class, which, well-educated and articulate, serves the administration effectively. The dominant cultural mode is a syncretic one: Chinese customs and values are being observed, forgotten, revived, passed on from one generation to the next and modified while Western forms of social organization are practiced. The ideology of acquiescence dominates, and in the late 1980s, an extension of British rule was even proposed by local residents. Reluctance to return to the motherland reflects the popular support for colonial capitalism, while the socialist experience next door is not favored. In short, the Hong Kong people seem more or less satisfied with their situation and have few postcolonial interests.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- New Chinese CinemasForms, Identities, Politics, pp. 180 - 201Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 1994

- 9

- Cited by