No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

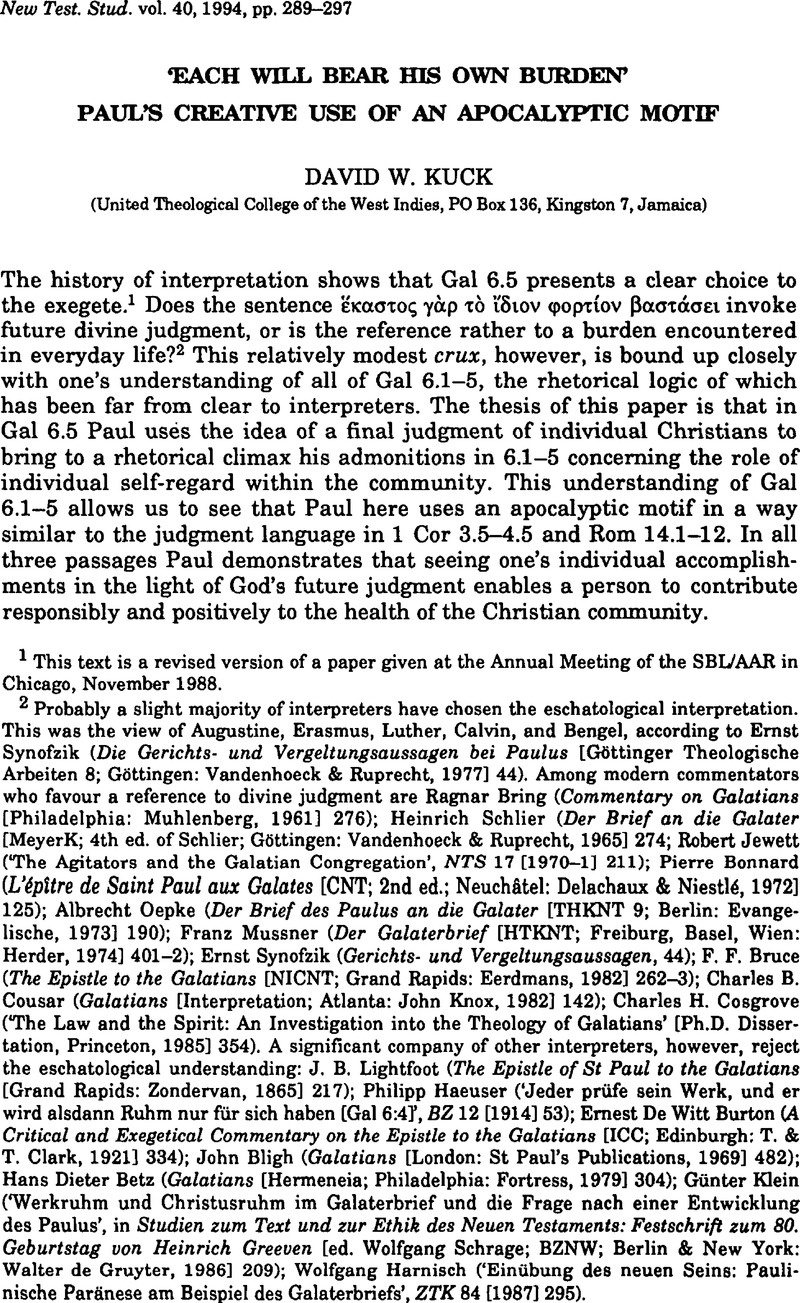

‘Each Will Bear his own Burden’: Paul's Creative Use of an Apocalyptic Motif

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Short Studies

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1994

References

1 This text is a revised version of a paper given at the Annual Meeting of the SBL/AAR in Chicago, November 1988.

2 Probably a slight majority of interpreters have chosen the eschatological interpretation. This was the view of Augustine, Erasmus, Luther, Calvin, and Bengel, according to Synofzik, Ernst (Die Gerichts- und Vergeltungsaussagen bei Paulus [Göttinger Theologische Arbeiten 8; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1977] 44)Google Scholar. Among modern commentators who favour a reference to divine judgment are Ragnar Bring (Commentary on Galatians [Philadelphia: Muhlenberg, 1961] 276)Google Scholar; Schlier, Heinrich (Der Brief an die Galater [MeyerK; 4th ed. of Schlier; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1965] 274Google Scholar; Jewett, Robert (‘The Agitators and the Galatian Congregation’, NTS 17 [1970–1971] 211)Google Scholar; Bonnard, Pierre (L'épître de Saint Paul aux Galates [CNT; 2nd ed.; Neuchâtel: Delachaux & Niestlé, 1972] 125)Google Scholar; Oepke, Albrecht (Der Brief des Paulus an die Galater [THKNT 9; Berlin: Evangelische, 1973] 190)Google Scholar; Mussner, Franz (Der Galaterbrief [HTKNT; Freiburg, Basel, Wien: Herder, 1974] 401–2)Google Scholar; Ernst Synofzik (Gerichts- und Vergeltungsaussagen, 44); Bruce, F. F. (The Epistle to the Galatians [NICNT; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1982] 262–3)Google Scholar; Cousar, Charles B. (Galatians [Interpretation; Atlanta: John Knox, 1982] 142)Google Scholar; Cosgrove, Charles H. (‘The Law and the Spirit: An Investigation into the Theology of Galatians’ [Ph.D. Dissertation, Princeton, 1985] 354)Google Scholar. A significant company of other interpreters, however, reject the eschatological understanding: Lightfoot, J. B. (The Epistle of St Paul to the Galatians [Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1865] 217)Google Scholar; Haeuser, Philipp (‘Jeder prüfe sein Werk, und er wird alsdann Ruhm nur für sich haben [Gal 6:4],’ BZ 12 [1914] 53)Google Scholar; Burton, Ernest De Witt (A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Epistle to the Galatians [ICC; Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1921] 334)Google Scholar; Bligh, John (Galatians [London: St Paul's Publications, 1969] 482)Google Scholar; Betz, Hans Dieter (Galatians [Hermeneia; Philadelphia: Fortress, 1979] 304)Google Scholar; Klein, Günter (‘Werkruhm und Christusruhm im Galaterbrief und die Frage nach einer Entwicklung des Paulus’, in Studien zum Text und zur Ethik des Neuen Testaments: Festschrift zum 80. Geburtstag von Heinrich Greeven [ed. Wolfgang, Schrage; BZNW; Berlin & New York: Walter de Gruyter, 1986] 209)Google Scholar; Harnisch, Wolfgang (‘Einubung des neuen Seins: Paulinische Paränese am Beispiel des Galaterbriefs’, ZTK 84 [1987] 295).Google Scholar

3 Even where there is disagreement on the outline of chapter 5 most commentators agree on taking 5.25–6.10 as a sub-unit: Schlier (An die Galater, 241); Betz (Galatians, 23 & 291); Brinsmead, Bernard H. (Galatians – Dialogical Response to Opponents [SBLDS 65; Scholars, 1982] 53)Google Scholar; Ebeling, Gerhard (The Truth of the Gospel: An Exposition of Galatians [Philadelphia: Fortress, 1985] 259–50)Google Scholar; Harnisch (‘Einübung des neuen Seins’, 292–6); Matera, Frank J. (‘The Culmination of Paul's Argument to the Galatians: Gal. 5.1–6.17’, JSNT 32 [1988] 85).Google Scholar

4 Some would take 5.26 with 6.1–5: Haeuser (‘Jeder prüfe sein Werk’, 54); Bonnard (Galates, 117); Mussner (Galaterbrief, 402); Harnisch (‘Einübung des neuen Seins’, 292). Others would take 6.6 with 6.1–5: Oepke (Galater, 10); Harnisch (‘Einübung des neuen Seins’, 292). Thus Harnisch sees 5.26–6.6 as the complete sub-unit. For 6.1–5 as a unit see Klein (‘Werkruhm und Christusruhm‘, 202).

5 Cousar, Galatians, 141; Klein, ‘Werkruhm und Christusruhm’, 202.

6 Betz (Galatians, 291), referring to 5.25–6.10. See the comments critical of this position by Klein (‘Werkruhm und Christusruhm’, 203); Harnisch (‘Einübung des neuen Seins’, 292 & 295–6); and Cosgrove, ‘Law and Spirit‘, 350.

7 Betz, Galatians, 291–2 and passim on the section. Similarly Ebeling, Truth of the Gospel, 259.

8 See the comments by Hays, Richard B. (‘Christology and Ethics in Galatians: The Law of Christ‘, CBQ 49 [1987] 268–9).Google Scholar

9 Betz, Galatians, 293–4.

10 Ebeling, Truth of the Gospel, 259.

11 Schlier, Galater, 269.

12 Betz, Galatians, 294.

13 Epictetus Diss. 3.24.43; 4 Mace 8.24; Ep. Arist. 8; Philo Somn. 2.105; De Jos. 36.

14 Ebeling, Truth of the Gospel, 260. See also Mussner, Galaterbrief, 397, 400–2; David J. Lull, The Spirit in Galatia (SBLDS 49; Scholars Press, 1980) 37; Cousar, Galatians, 141.

15 Burton (Galatians, 323) wrongly takes Paul to refer to two different groups. One group in unrestrained liberty carelessly provokes other believers. The other group is envious of the freedom which some Galatian Christians enjoy. He reads too much from 1 Cor 8 and Rom 14–15 into these words.

16 George Howard, Paul: Crisis in Galatia (SNTSMS 35; Cambridge University, 1979) 14; Matera, ‘The Culmination of Paul's Argument to the Galatians’, 85–6. Some have thought that Paul is here arguing against libertines (Jewett, ‘The Agitators and the Galatian Congregation’, 211–12) or against nomists (Brinsmead, Galatians – Dialogical Response to Opponents, 199–200). Lull (The Spirit in Galatia, 5,18 notes 20 and 37) puts great stress on the idea that Paul here is attacking opponents who are self-seeking lovers of fame, with reference to 5.26; 6.3; 4.17; and 6.12–13).

17 Betz, Galatians, 295.

18 Harnisch, ‘Einübung des neuen Seins’, 293.

19 Lightfoot, Galatians, 216; Synofzik, Gerichts- und Vergeltungsaussagen, 44.

20 Cousar, Galatians, 142–3. On the reference of τόν νόμον το![]() ριστο

ριστο![]() as an appeal to Christ as a paradigm see Hays (‘Christology and Ethics in Galatians’, 273–6, 286–90).

as an appeal to Christ as a paradigm see Hays (‘Christology and Ethics in Galatians’, 273–6, 286–90).

21 Betz (Galatians, 298–9) fits this admonition within the hellenistic philosophical tradition, particularly concerning friendship.

22 Mussner, Galaterbrief, 398–9; Cosgrove, ‘Law and Spirit’, 351. Strelan, John G. (‘Burden-Bearing and the Law of Christ: A Re-examination of Galatians 6:2’, JBL 94 [1975] 266–76)Google Scholar must engage in much special pleading in order to come to the conclusion that this admonition refers to financial obligations.

23 Klein, ‘Werkruhm und Christusruhm’, 203.

24 Burton, Galatians, 330.

25 Betz, Galatians, 301.

26 Mussner, Galaterbrief, 400.

27 Lull, The Spirit in Galatia, 128.

28 Betz (Galatians, 302) sees v. 4 related to v. 3 mainly by the catchword δοκ.

29 Rom 14.20; 1 Cor 3.13–15; 9.1; 15.58; 16.10; Phil 2.30; 1 Thess 1.3; 5.13.

30 Barrett, C. K., Freedom and Obligation: A Study of the Epistle to the Galatians (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1985) 80–1.Google Scholar

31 For the hellenistic material see Betz, Galatians, 302.

32 This is also the implicit exhortation of 1 Cor 3.13, although here it is God's judgment that is said to test (δοκιμάσει) one's work.

33 So correctly Mussner, Galaterbrief, 401; Klein, ‘Werkruhm und Christusruhm’, 209. Even Cosgrove (‘Law and Spirit’, 353) misunderstands this point, taking v. 4 to refer to an eschatological boast before God.

34 Harnisch (‘Einübung des neuen Seins’, 295) says that Paul has an ironic tone here. Boasting is by definition an act that can only be done in relation to others. Therefore, Paul is engaging in reductio ad absurdum in order to effectively do away with all boasting. But this is to press Paul too hard.

35 Synofzik (Gerichts- und Vergeltungsaussagen, 44) wrongly thinks that τό καύχημα ![]() ξει refers to future judgment. Rather, the contrast is being drawn between two arenas for boasting in the present community.

ξει refers to future judgment. Rather, the contrast is being drawn between two arenas for boasting in the present community.

36 Cosgrove, ‘Law and Spirit’, 354.

37 Burton, Galatians, 334; Betz, Galatians, 304; Harnisch, ‘Einübung des neuen Seins’, 295.

38 This sometimes leads to forced attempts to see a difference in the meaning of βάρος and φορτίον Lightfoot, Galatians, 217; Jones, Arthur, ‘βάρος and φορτίον’, Expository Times 34 (1923) 333Google Scholar. On this see Cosgrove, ‘Law and Spirit’, 354.

39 Betz, Galatians, 303.

40 Cosgrove (‘Law and Spirit’, 356) refers to this final individual judgment as the vindication of the believer's life as an authentic ‘work’ before God.

41 Cosgrove, ‘Law and Spirit’, 354. Synofzik (Gerichts- und Vergeltungsaussagen, 44) is wrong on this, in spite of his otherwise helpful treatment. So also Mussner (Galaterbrief, 401–2).

42 See Betz, Galatians, 303–4.

43 Cosgrove, ‘Law and Spirit’, 350. In the Greek OT φορτίον can be used literally of a load such as a pack animal would carry (Judg 9.48–9 A; Isa 46.1; Sir 33.25). It can be used figuratively to refer to the burden of sins (Ps 37.5), the burden of a fool's speech (Sir 21.16), or the burden a person represents to a king (2 Kgdms 19.36) or to God (Job 7.20). In early Christian writings the word can be used literally (Acts 27.10; Herm. Sim. 9.2.4), or figuratively to refer to the burden of rules (Matt 23.4; Luke 11.46) or to the light burden of Jesus (Matt 11.30). In Greek literature the word can, of course, be used literally (Xenophon Mem. 3.13.6). It is used figuratively in a wide variety of ways: the burden of a wife (Menander Sent. 459; Anaxandrides Comic, Frag. 53), of old age (Anaxandrides Comic, Frag. 53), of poverty (Menander Sent. 660), that a monarch bears in ruling (Demosthenes Or. 11.14), of the body (Poimandres 10.8b; Sextus Sent. 335). It can refer to the burden of practising philosophy (Diogenes Laertius 7.170; Epictetus Diss. 2.9.22). The wise person tries to carry only what he can handle (Antiphanes Comic, Frag. 3; Teles p. 10, line 7 [Hensel]). It can refer to the difficulties and calamities that befall human life (Epictetus Diss. 4.13.16; Plutarch De exilio 599CD).

44 Translation by Bruce M. Metzger in OTP, vol. 1, 540. The words in brackets are in the Syriac text but not in the Latin. The Latin text of the last clause reads: omnes enim portabunt unusquisque tune iniustitias suas aut iustitias. Cosgrove (‘Law and Spirit’, 354–5) also notes this as the closest parallel to our text.

45 In the ‘Third Vision’ of 4 Ezra 6.35–9.25 it is evident that, although a corporate salvation for Israel is still a considered possibility, the more dominant idea is that Israel (and perhaps some Gentiles as well) will be divided on the basis of individual merit. On this see Thompson, Alden L., Responsibility for Evil in the Theodicy of 4 Ezra (SBLDS 29; Missoula: Scholars, 1977) 201–2Google Scholar; Myers, Jacob M., I and II Esdras: Introduction, Translation, and Commentary (AB 42; Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1974) 256Google Scholar; Collins, John J., The Apocalyptic Imagination (New York: Crossroad, 1984) 160–2Google Scholar; Sanders, E. P., Paul and Palestinian Judaism (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1977) 409–15.Google Scholar

46 Pss. Sol. 9.5; 2 Apoc. Bar. 54.14–16; Matt 16.27; 1 Pet 1.17; 2 Tim 4.14; Rev 2.23; 20.13; 22.12; Rom 2.6.

47 Cousar, Galatians, 145–6; Cosgrove, ‘Law and Spirit’, 354. It is best, with most commentators, to regard v. 6 as the introduction of another topic concerning relations with the community. Paul's eschatological statements in w. 7–8 serve to ground the admonition in v. 6, even though the link is not a strong one. Thus there is a certain parallelism in structure between 6.1–5 and 6.6–10, with the initial admonitions being grounded in eschatological pronouncements. So Krentz, Edgar, ‘Galatians’, in Galatians, Philippians, Philemon, 1 Thessalonians (Augsburg Commentary on the New Testament; Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1985) 88–9.Google Scholar

48 Cosgrove, ‘Law and Spirit’, 354. On this verse see Synofzik, Gerichts- und Vergel-tungsaussagen, 33.

49 Synofzik, Gerichts- und Vergeltungsaussagen, 72–3; Lull, The Spirit in Galatia, 173.

50 Synofzik, Gerichts- und Vergeltungssaussagen, 44.

51 On Rom 14 see Meeks, Wayne A., ‘Judgment and the Brother: Romans 14.1–15.13’, in Tradition and Interpretation in the New Testament: Essays in Honor of E. Earle Ellis (ed. Hawthorne, Gerald F.; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1987) 290–300Google Scholar. On 1 Cor 3–4 see Kuck, David W., Judgment and Community Conflict: Paul's Use of Apocalyptic Judgment Language in 1 Cor 3:5–4:5 (NovT Supp. 66; Leiden: Brill, 1992).Google Scholar

52 See also 1 Cor 11.27–34, where social tensions at the Lord's Supper are to be avoided by means of self-examination of attitudes toward the community in the light of the future judgment. But here Paul approaches the problem more as a warning about the corporate judgment of the world and those who bring the world's social behaviour into the central communal ritual of the church.

53 Synofzik (Gericfits- und Vergeltungsaussagen, 43–4) notices some of the similarities among these passages.